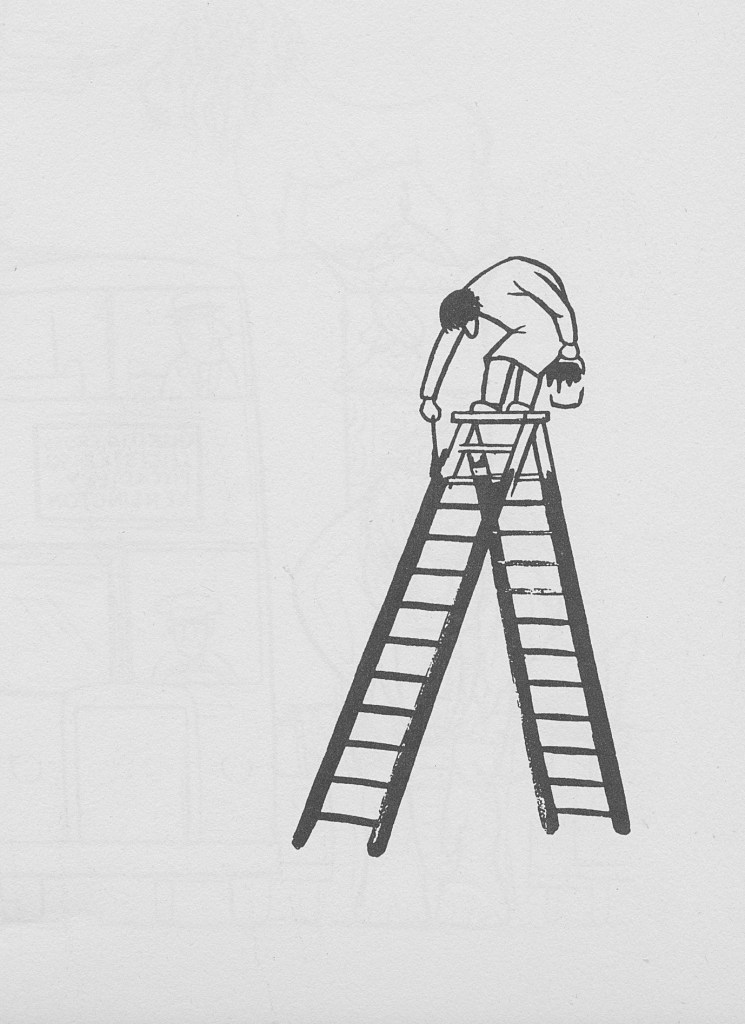

FEATURE image: Chaval’s cartoons, mainly wordless, are often derisive, ironic and filled with dark humor. In the 1950s Chaval was mentioned in American publications with cartoonists such as James Thurber, Charles Addams and William Steig.

By John P. Walsh

The 53-year-old French cartoonist’s suicide in Paris in winter 1968 served as a tragic end to a witty career. Born Yvan Le Louarn near Bordeaux in 1915, Chaval left a suicide note on the apartment door that read “Mind the gas.” But today it is his actions as a young man in his late 20s that mark him for controversy.

Chaval’s professional name is a bastardization of Chevel, an early twentieth century architect for whose work the term “architecture naïve” was coined. While Chevel came to fantastical architecture after being a poor farmer, Chaval trained for years at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the nation’s foremost art school.

It is a specific period in the cartoonist’s past that erupted into a controversy in late spring 2008 as a major French art museum mounted a retrospective exhibition of Chaval’s career.

During the nearly incredible period of World War II, Chaval created drawings after 1940 with a racist and anti-Semitic slant for publication in Le Progrès, a Vichy newspaper. His drawings were characterized as “Pro-German Vichy and not just” by Pascal Ory, a leading French cultural historian of the Université de Paris-I-Panthéon-Sorbonne. When the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux hosted an exhibition of 120 of Chaval’s pen-and-ink cartoons in summer 2008 none of his wartime anti-Semitic drawings was displayed. In an article in La Croix, the daily Paris Roman Catholic newspaper, Professor Ory revealed the nature of some of these hidden racist works as the exhibition opened.

By the mid 1950s Chaval was an international sensation, his cartoon work mentioned in the same breath in American publications with icons such as James Thurber (1894-1961), Charles Addams (1912-1988) and William Steig (1907-2003). Immediately after the war Chaval was cleared of wrongdoing and started to be published in top French publications—Punch, Le Figaro, Le Nouvel Observateur, Paris Match. He won the industry’s highest awards and remained at the top of his field until the time of his death.

In a June 5, 2008 article Professor Ory described Chaval’s wartime cartoons as “compelling” of racist anti-Semitism. One published Chaval wartime cartoon Professor Ory described—and the Bordeaux fine arts museum director confirmed its existence—shows two figures with exaggerated noses and wearing yellow stars on their coats. One of them wears two yellow stars and says to the other: “He made me a good price!” Professor Ory criticized not only the drawing’s crude racist ontology but that the Bordeaux art museum would seek to ignore or even cover up the cartoon’s existence in Chaval’s oeuvre. “I’m surprised,” Ory said, speaking in 2008, “that after thirty years of historiography, we are always looking to conceal the period of collaboration under the Occupation in France.”

That the art museum buried Chaval’s early racist work from view without explanation did not stop the museum director, M. Olivier Le Bihan, from defending an impugned Chaval after his controversial work was publicized: “We do not have the right to condemn a man because he made a tendentious drawing. Remember that after the war a trial cleared Chaval of some of the anti-Semitic cartoons ascribed to him. Chaval was called a humanist in Robert Merle’s 1954 Holocaust novel (“Death is my Trade”).”

Professor Ory, author of the classic Les Collaborateurs 1940-1945 (published in 1976), counters that it is “absurd” for the museum to justify the overriding purpose of an art exhibition as “first drawing” or that Chaval “does not deserve this trial of intent” because “he did it to eat.” Professor Ory states there is a “dialogue gap” between art historians and historians that leads to an “endemic lack of historical understanding” of the issues involved in an art exhibition resulting only in an ensuing public spectacle of controversy. Ory points to a similar mistake being made in another 2008 exhibition held in Paris of photographs by collaborationist André Zucca (French, 1897-1973). This exhibition caused a public furor for not being specific about the conditions under which these images of the city during the Nazi Occupation had been made.

Ory contends that Chaval’s case is not simply a matter of a hungry young artist making due in wartime. There is further documentation of Chaval’s friendly relations with racist editors and writers on the Vichy newspaper. Beyond these facts is Professor Ory’s principled belief that “the problem of political engagement is not secondary” to any artist’s life or work. Chaval, professor Ory concludes, is a “draftsman collaborationist” – and though his political affiliations do not detract from his artistic talent it becomes important for the art historian and curator to explain the historical context including “the artist’s overall character” to the viewer. This practices intellectual honesty and makes the enterprise of art making and art exhibition “more human,” according to Ory.

SOURCES: The Best Cartoons From France, Edna Bennett, Philippe Halsman, Simon & Schuster, 1953; C’est la vie: The Best Cartoons of Chaval, Citadel Press, 1957; http://www.la-croix.com/Culture-Loisirs/Culture/Actualite/A-Bordeaux-l-exposition-Chaval-souleve-la-polemique-_NG_-2008-06-05-672010.

(Oh. I know who you are)! :o)

Regarding the article: It does go to demonstrate how any person, artist included, is often only a product of his surroundings, times and ingrained beliefs (whether for good or evil).

I think that while we come to think that artists (of all people) are always looking for truth and some universal sense of humane justice (and are therefore looked to as beacons of altruism and outraged by the injustices and/or weaknesses), some others surely “process” their culture and certain situational complexities by being in lock-step to the ideologies and pressures by which they choose to accept. After all, an artist is always a real flesh and blood person first and foremost. We only become something else when time or others attempt to analyze us as to place us in some broader, understandable context (which is often skewed or completely erroneous in perception).

It is why the art is suppose to do the talking for us. All is revealed therein, I suppose.

Pingback: Chaval: Forgotten, Controversial French Gag Cartoonist » Ben Towle: Cartoonist, Educator, Hobo