FEATURE image: Allegory of Venus and Cupid, c. 1600, Imitator of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio, Italian, c. 1485/90-1576), oil on canvas, 51 1/8 x 61 1/8 in. (129.9 x 155.3 cm). Charles H. and Mary F.S. Worcester Collection, 1943.90.

By John P. Walsh

The pleasant if heavily-restored late 16th century allegorical painting in the collection of The Art Institute of Chicago is today called Allegory of Venus and Cupid and dated to around 1600. Attributed to an “imitator” of Titian it remains in museum storage (“Not on Display”).

When this same painting was “rediscovered” around 1930 it was hailed as a Titian masterpiece and over the next 15 years was talked of that way in the general press and in some quarters of the art press. It delighted crowds who came to see it hang on the walls of The Art Institute of Chicago and The Cleveland Museum of Art. Called The Education of Cupid and dated to the 1550s, it was compared favorably with Titian’s famous allegorical subject paintings in Paris’s Louvre and in Rome’s Galleria Borghese.

The painting through the Great Depression and World War II was labeled “Titian,” but among expert connoisseurs there existed a longstanding dismissal of that attribution ever since its first known “resurfacing” in the mid1830s at Gosford House in Scotland.

In Italian his name is Tiziano Vecellio, but in English the artist is famously known as Titian (1485-1576)

Titian was part of a family of artists who had been civic leaders in 13th-century and 14th-century Italy, such as mayors, magistrates, and notaries. Offspring of two Vecellio brothers in the fifteenth century became artists. One of the brothers was ambassador to Venice where the family had a timber trade there. The ambassador’s grandsons became Venetian-trained painters. The younger grandson was the great Titian.

Titian became the leading painter in Venice and an influential artist throughout Sixteenth-century Italy. His cousin Cesare Vecellio (1530-1601) was an engraver and painter trained in Titian’s workshop. These Vecellio cousins and their sons became artists and were allowed to use the appellation “di Tiziano” which would bring them attention. Yet these family members were, along with later followers of Titian, artistic mediocrities.

The painter of The Art Institute of Chicago’s allegory entitled Allegory of Venus and Cupid is only identified as an “imitator” of Titian. Its allegorical motifs share similarities with Titian’s and this is perhaps partly why this Old Master painting by an unknown follower of Titian was mistaken for the master himself when it resurfaced on the art market in 1927.

Called The Education of Cupid and dated to the 1550s, it traded back and forth to the dealer for almost a decade until it was bought in 1936 by a well-connected Chicago couple who collected sixteenth-century Venetian paintings. The Wemyss ‘Allegory’ (named for its former British owner, Lord Wemyss) came to Chicago out of what amounted to be a Scottish attic.

It gained ready acclaim as a rediscovered Titian and since its subject was reminiscent of Titian’s Allegory of Marriage (1533) in the Louvre and a Titian subject allegory in the Galleria Borghese, the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ in Chicago was hailed as completing a triumvirate of Titian’s greatest allegorical compositions.

The problem was that this Chicago Titian was not a Titian at all, although it took about 10 years for that fact to gain modern acceptance.

After the purchase, the new owners immediately lent their Titian to The Art Institute to mount on its gallery walls. It would hang next to the collector couple’s verifiable Tintoretto, Veronese, and G.-B. Moroni. The museum eventually acquired the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ in 1943, but not before it toured The Cleveland Museum of Art during their “Twentieth Anniversary Exhibition” in 1936 and viewed with enthusiasm as a Titian.

The collector purchase and subsequent loan to the Art Institute was front page news in Chicago. The director of the museum at the time, Robert Harshe, compared the work in importance to only two others in The Art Institute at that time – El Greco’s Assumption of the Virgin (1577-79) and Girl at the Open Half Door (1645) attributed to Rembrandt. Curiously, this painting first attributed to Rembrandt has been itself increasingly questioned in terms of its high authorship. One of the first historical European paintings to enter the museum’s permanent collection, Girl at the Open Half Door is today identified with the moniker “and Workshop” to indicate the possibility that it was created by a student under the master’s supervision.

Soon after its acquisition by The Art Institute, the Titian attribution was loudly critiqued in print and eventually dropped. The subject of the painting is of a girl who appears before Venus to be initiated into the mysteries of Love. At the girl’s right are Venus and the boy Cupid with an arrow. In the background two satyrs raise items such as a basket with two doves and a bundle of fruit.

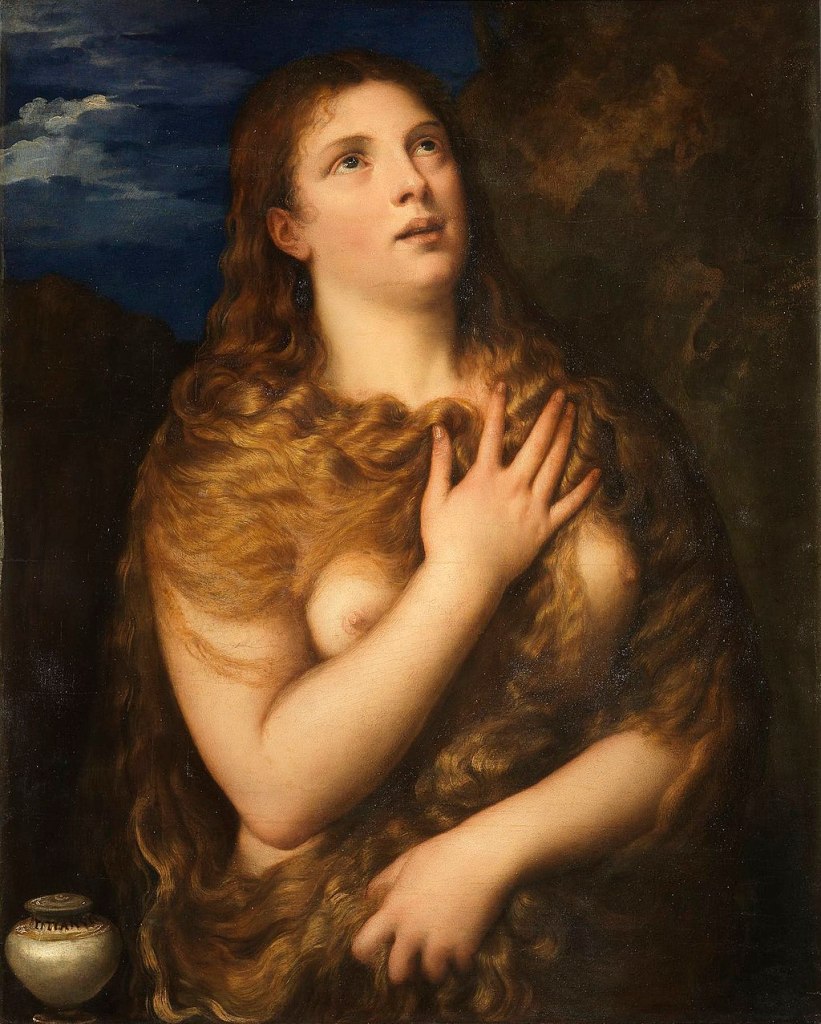

Allegories were popular in Italian Renaissance art to convey social, political, economic and religious messages using historical and mythological figures. This painting’s figures, however, appear to be derivative of specific Titian works. Further, it possesses little of the technical brilliance or psychological revelations found in Titian’s work such as in Triple Mask or Allegory of Prudence (c. 1570, London, National Gallery). For example, Titian’s imitator gives the figure of the girl the same dramatic hand gesture found in Titian’s Venus with a Mirror (c. 1555, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. ). Insofar as the girl’s skyward gaze and flowing hair, the imitator cites The Penitent Magdalene (1531-33, Florence, Palazzo Pitti).

In addition to the painting’s derivative character of well-known Titian works, what most connoisseurs recognized by 1945 was what they called its “very modern” execution. This referred to its sharp color contrasts and figurative forms which developed only after Titian’s time. Connoisseurs also noted that Titian differentiated sharply between hair and ornament and that his female figures’s hair is neatly braided, whereas the hair is “in a mass” in the Wemyss ‘Allegory’.

These characteristics pointed to the picture being related less to authentic Titians in Paris and Rome and more to those attributed dubiously, even spuriously, to Titian in Munich and at the Durazzo Palace in Genoa. Though this inauthenticity of Chicago’s Wemyss “Allegory” could have been questioned at the start of its appearance in Chicago in 1936, the museum was not adhering closely to the historical connoisseurship.

Sir Joseph Archer Crowe (British, 1825-1896) and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (Italian, 1819-1897) had seen all three of the spuriously attributed Titians in Munich, Genoa, and at Gosford House which was now in Chicago. It was well known the pair excluded all three from their Titian catalog except to note that they were imitations which had been notably damaged and restored. Chicago museum research in the late 1930s was also aware of Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s attributive work for they cited them in official publications on the Wemyss ‘Allegory,’ but overlooked their conclusions.

With the museum’s acquisition of the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ in 1943 Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s negative attribution for it was no longer ignored or denied. About its reworking in England one tempting and likely wishful speculation was that the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ was restored by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) but that claim remains unsubstantiated. Further facts contextualized in the deft historical hands of modern connoisseurship left the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ out in the Titianesque cold as an imitator. In the case of the Chicago painting it was by historical comparison with compositional arrangements in known Titians that the compositional arrangements in the Munich and Chicago paintings were deemed by Crowe and Cavalcaselle to be done by imitators. Historically for Titian it would be nonsensical or “unique” for Titian to have manipulated the figures in that way at that time.

By the mid1940s the Chicago painting was searching for a new name attribution, since Crowe and Cavalcaselle did not give it one. The notion that it was done by Damiano Mazza (active after 1573), an obscure 16th century artist and student of Titian, was proposed but later dismissed.

Some of the confusion over the attribution to Titian of the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ is based on erring connections made using erring extant evidence. For example, the conjecture of Vienna School-trained art historian of Venetian art Hans Tietze (Czech, 1880-1954) that a sketch by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)–which Tietze wrongly believed was made at Chatsworth House of a painting once attributed to Titian–shared similar motifs with the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ is a thin thread for possible attribution to Titian. It may be argued that the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ shares very little with the Van Dyck sketch except for the satyr lifting a basket. Further, the painting which Van Dyck sketched is no longer attributed to Titian and has long been in the Galleria Borghese in Rome as a minor Venus and Cupid with Satyr Carrying a Basket with Fruit now attributed to Paolo Veronese. It was in Rome where Van Dyck must have made his sketch, not England, and it was there he misidentified it as Titian. It is a tenous trail of misleading evidence that became the prompt to a connoisseur’s mistaken thought.

Nuptial paintings

One persuasive conclusion on attribution today for the Wemyss ‘Allegory’ was offered by Hans Tietze’s wife, the historian of Renaissance and Baroque art, Erika Tietze-Conrat (1883-1958). Tietze-Conrat believed that The Art Institute painting resides in a pool of works done by assistants and imitators who combined varied elements of Titian’s allegories as found in the Louvre’s Allegory of d’Avalos (the aforementioned Allegory of Marriage) and the Borghese’s Education of Cupid.

Erwin Panofsky (German, 1892-1968) postulated that those known Titians were nuptial paintings. Building on that premise, Tietze-Conrat postulated that numerous reproductions were made by Titian followers so to create nuptial paintings for their patrons to suit their needs. The derivative works shared the intimacy of a private format with a recognizable cast of 16th century depictions of mythological actors and the evocation of a Titianesque mood.

Today the Art Institute of Chicago has renamed their Wemyss “Allegory” as Allegory of Venus and Cupid and dated it to “around 1600.” The museum removed Titian and every other named attribution. Attribution has been returned to the term that connoisseurs Crowe and Cavalcaselle gave the painting in 1881, namely, “imitator.”

“The execution here is very modern,” the pair wrote in their Life and Times of Titian in 1881. “It is greatly injured, but was apparently executed by some imitator of Titian.” Their late 19th century judgment hold fast today.

NOTES –

“first known “resurfacing” in the mid1830s in Scotland at Gosford House” – http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/46314?search_no=6&index=4 ,retrieved Dec 29, 2014.

On Titian and Vecellio family – Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist Art, Volume II, edited by Jane Turner, Macmillan Reference Limited, 2000, p. 1695.

For provenance since 1835 – see http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/46314?search_no=6&index=4 ,retrieved Dec 29, 2014.

“ready acclaim as a rediscovered Titian…”; “lent their Titian to The Art Institute to mount……”; “Cleveland… ‘Twentieth Anniversary Exhibition’ in 1936…” – “A Great Titian,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) Vol. 31, No. 1 (Jan., 1937), p. 8; “Famed Titian Work Acquired by Chicagoans,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1936, p. 28; “The Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Worcester Gift,” Daniel Catton Rich, Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Mar., 1930), pp. 29-31 and 40. The Chicago collectors were Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Worcester, a museum Vice-President and lumber and paper manufacturer.

“…director of the museum… compared the work in importance to El Greco’s ‘Assumption of the Virgin’ and Rembrandt’s ‘Girl at the Open Half Door’” – “Famed Titian Work Acquired by Chicagoans,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1936, p. 28.

“….Allegories were popular in Italian Renaissance art…”- http://www.iub.edu/~iuam/online_modules/iowc/b_003.html,retrieved December 29, 2014.

“little of the technical brilliance or psychological revelations found in…Triple Mask…” – H. E. Wethey, The Paintings of Titian: Complete Edition, vol. 2, The Portraits, Phaidon, New York, p. 50.

“its ‘very modern’ execution”; “in a mass” – The Wemyss Allegory in the Art Institute of Chicago, E. Tietze-Conrat. The Art Bulletin Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1945), p. 269.

“It was widely known the pair excluded all three from their Titian catalog…” – “A Great Titian Goes to Chicago,” Art News 35, 5 (1936), p.15 (ill.).

“Chicago museum research in the late 1930s was aware of Crowe and Cavalcaselle’s attributive work… overlooked their conclusions…” – Footnote #4, The Wemyss Allegory in the Art Institute of Chicago, E. Tietze-Conrat. The Art Bulletin Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1945), p. 269.

“…restored by Sir Joshua Reynolds…” – The Wemyss Allegory in the Art Institute of Chicago, E. Tietze-Conrat. The Art Bulletin Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1945), p. 269.

“done by Damiano Mazza…” Ibid., p. 270.

Conjecture of Hans Tietze; Erika Tietze-Conrat’s postulation – Ibid., p. 271.

“the execution here is very modern… It is greatly injured, but was apparently executed by some imitator of Titian.” – Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Life and Times of Titian, London, 1881,

II, p. 468.