FEATURE image: Portrait of Chief Joseph in native dress with ornaments, 1900, by Lee Moorhouse (1850–1926). Public Domain.

INTRODUCTION.

by John P. Walsh

Joseph (1840-1904) was the leader of one of the Nez Percé tribes. The band amounted to about 200 people who lived in the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon. White settlers wanted their grazing lands. After the death of Wellamotkin in 1871, a Nez Percé chief and Joseph’s father, the 31-year-old tall and handsome Joseph began to have conflict with the whites.

At the time of Joseph’s birth in 1840 there were around 6,000 Nez Percé, most of them living in small fishing villages next to fecund streams and rivers. Each village had its own “chief” and young Joseph visited these villages with his father where he learned about the people and the lore of his nation.

Once each winter was over, the Nez Percé, like other Native American tribes ranged beyond their own territory. These could be friendly visits like buffalo hunts or more contentious meetings. These cultural interchanges influenced Nez Percé as they influenced others. For hundreds of years the Nez Percé were mostly influenced by the Pacific Coast culture through the Chinook tribes more than the Plains tribes.

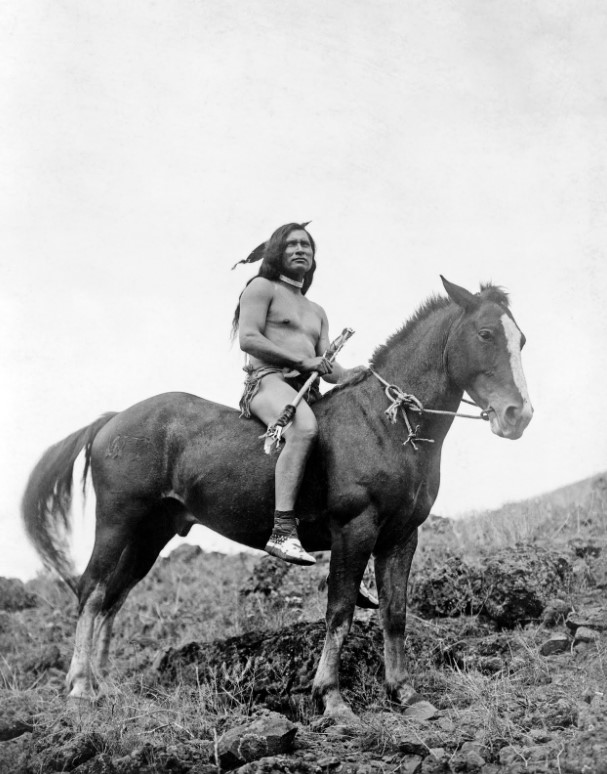

In the 1730s the Nez Percé learned about horses from Native Americans like the Apache who had contact with Spanish settlements in the south. With horses the Nez Percé traveled farther and more often into the Plains so that by the 1800s the Nez Percé were more a Plains tribe though they maintained their roots in the Pacific Northwest.

It was at the start of the 19th century that those venturing Nez Percé came into contact with whites and bought guns. The home tribe didn’t have to wait long to encounter the whites – in 1805 Lewis and Clark reached the Columbia River. Promised more guns, none appeared for a couple of years and these by way of a Canadian trader.

The Nez Percé got their name from this French-Canadian trader who saw the nose piercings that the tribe used to affix ornaments to themselves. In 1812 the American traders that Lewis and Clark promised finally arrived but quickly left and the Canadians took over.

By the late 1820s the Nez Percé roamed farther east and encountered more white fur traders among whom they lived, traded, fought, and frequently intermarried. It was in this period that the first Christian missions, both protestant and Catholic, began their influence among the Nez Percé. In the 1830s the Nez Percé journeyed to St. Louis to recruit missionaries which was successful. Joseph’s father, Wellamotkin, became a Presbyterian and Joseph was baptized at birth. By 1850, with the influx of white settlers into Oregon, the Native Americans expelled the missionaries though this divided the tribe. Joseph retreated to the Wallowa Valley away from contact – and conflict – with the new arrivals.

In 1855 the Nez Percé signed a treaty that created a large reservation for themselves. Joseph was considered a Christian and friendly to the whites. In 1860 when gold was discovered on the Nez Percé reservation the rampant trespassing of whites was unacceptable to Joseph. White crime against Nez Percé went up and whites built settlements on Indian land. Federal agents arrived and offered a smaller new reservation to the Nez Percé. The proposal was initially opposed by Indian leaders but Federal agents bought off the local chiefs one-by-one and, in 1863, a treaty was signed.

The new reservation was one quarter the size of what it was and did not include the Wallowa Valley. Joseph and most of the rest of the chiefs refused to sign. It was at this time that Joseph renounced his protestant Christianity as the white man’s religion. The Nez Percé on the new reservation saw the arrival of more and more whites. Though the Wallowa Valley where Joseph lived remained outside the white settlements’ orbit that changed over a short time.

In 1871, after Joseph buried his father and became chief, white settlers began moving into the Wallowa Valley. Joseph protested to the U.S. Government and, in 1873, President U.S. Grant ordered the whites to withdraw and formally recognized the Wallowa reservation.

But the White House in Washington D.C. was far away and the whites refused to leave. They threatened Joseph with extermination if the Nez Percé didn’t leave – and invited increasing numbers of white settlers who poured into the valley. The Oregon governor took the side of the white settlers and President Grant was forced to rescind his decision that favored Chief Joseph.

Chief Joseph – known as Heinmot Tooyalakekt (“thunder travels to lofty mountains”) – counseled delay. He moved his tribe farther from the encroaching white settlers and appealed to the U.S. Government again whose review of land claims and treaties advised siding with the Indians.

The U.S. Government did nothing until they appointed a panel in November 1876 with the power to make a final decision about the competing claims. Looking to dominate and persuade Chief Joseph, they were not able to do so by argument.

But events on the ground were intensifying between whites and Nez Percé so much so that violence between them was expected. The commissioners made their decision. Whether Nez Percé signed the 1863 or not all Nez Percé must go to the new small reservation or be taken there by force. The whites would get the Wallowa Valley. The deadline was April 1,1877.

As the deadline approached the Nez Percé appealed to the commission to let them continue to live in the Wallowa Valley but the decision was final. A new deadline of June 12, 1877 was set. Joseph was called a coward by his tribe for abiding by the order to go to the reservation.

That night a Nez Percé youth avenged the murder of his father by whites by killing 4 whites and wounding 1 more. Nez Percé killed 15 more whites in the next couple of days – and struck terror in the hearts of white settlers.

Chief Joseph counseled diplomacy but most of the Nez Percé didn’t listen to him and left for hiding places. Joseph was watched closely by his own tribe that he would not abandon them or betray them to the soldiers. Chief Joseph and his buffalo-hunting younger brother Ollokot finally decided to join the Nez Percé to fight the whites.

Soldiers were deployed to force the Nez Percé onto the reservation. With Nez Percé informants they planned to attack the hostile Nez Percé in their encampment. The Indian response was to buy time to escape. A white flag of truce went on ahead of the small Nez Percé party to meet the soldiers. There was an exchange of gunfire and the battle was on. The soldiers lost 34 dead, a third of the command, while the Nez Percé lost none and two wounded. The victors retrieved scores of guns and ammo that the fleeing soldiers left behind.

Reinforcements were called in – on both sides. Rumors ran wild. There was a massacre of reservation Nez Percé mistaken for hostiles. As the soldiers advanced the hostiles cut in behind them and the white settlers the soldiers were supposed to be protecting lay exposed to the hostiles. These Nez Percé advanced and massacred parties of soldiers, civilian volunteers, and terrified settlers.

Nez Percé picked up about 40 warriors but also whole communities of women and children to protect. Joseph was being given credit for this successful war campaign though it was other war leaders who led the strategy and tactics.

By July 11, 1877, there was 400 soldiers and 180 others who were pursuing the Nez Percé. They attacked and the Nez Percé responded. The battle went on for two days though the Nez Percé were outnumbered 6 to 1. The army lost 13 killed and 27 wounded and the Nez Percé lost 4 killed and 6 wounded – and escaped again. The Nez Percé decided it was time to evacuate the area.

On July 16, 1877 Chief Joseph agreed to the exodus to Montana. The army decided to pursue them. Army reinforcements were called out of Montana to intercept the Nez Percé. Chief Joseph decided to talk with them. Promising to be peaceful and pay for any supplies on his way to the Crows, he reassured the volunteers. In Montana. the Nez Percé rested though they were being pursued by new reinforcements. On August 8, 1877, the Nez Percé were attacked. The Nez Percé were surprised but reorganized and counter attacked and escaped with much of the army’s hardware and ammo. The army lost 33 soldiers dead and 38 wounded. Fourteen of 17 officers were among the casualties. But at least 60 Nez Percé were killed in the battle of Big Hole.

The Nez Percé decided to escape to Canada. Lean Elk replaced Looking Glass as supreme war chief. On and on the Indians hurried. On September 13, 1877 the Nez Percé were overtaken by U.S. cavalry. But, at Canyon Creek, the Nez Percé escaped with three wounded while 3 cavalrymen were killed and 11 were wounded.

Just 30 miles from the Canada border and confident that they had outrun their pursuers, the Nez Percé took a much-needed rest. This pause became their last stand.

The army arrived with 600 men that included infantry, cavalry, and Cheyenne warriors. This force intercepted the Nez Percé on September 30, 1877. They attacked and, from Nez Percé gunfire, the army had 2 officers and 22 soldiers killed and 4 officers and 38 soldiers wounded. Another contingent of army successfully worked to cut the Nez Percé camp into pieces. A siege ensued. The army commander lured Joseph to a diplomatic talk and then took him prisoner/hostage. The Nez Percé retaliated by taking an army officer prisoner/hostage. A swap was quickly agreed to.

The arrival of army reinforcements on October 4, 1877 spelled the end for the Nez Percé hold outs. Negotiations began and the Nez Percé were split – some argued to keep fighting. Joseph agreed to surrender. When the parlay ended one of chiefs who argued to keep fighting was shot in the head by a stray bullet as he stood up from discussion with the white man.

SOURCES: The Patriot Chiefs, Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., Viking Press, NY, 1961, pp. 312-340.

When I am gone, think of your country. You are the chief of these people. They look to you to guide them. Always remember that your father never sold the country. You must stop your ears whenever you are asked to sign a treaty selling your home. They have their eyes on this land. My son, never forget my dying words, this country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and mother. Wellamotkin to Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, 1871.

Somebody has got our horses. Reaction to violation of surrender treaty terms by U.S. Government. “When the terms of surrender were violated by the government, [Chief] Joseph did not dig up the tomahawk and go on the warpath again…. He…. spoke with a straight tongue , and was a gentleman of his word. Nor did he blame [Maj. Gen. O. O.] Howard or [Col. Nelson A.] Miles for what his people suffered. He remarked only the above. (Quoted in Saga of Chief Joseph, H. A. Howard, University of Nebraska Press, 1978, p. 348.)

We love the land. It is our home. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, November 1876.

Suppose a white man goes to my neighbor and says to him, ‘Joseph has some good horses. I want to buy them, but he refuses to sell.’ My neighbor answers, ‘Pay me the money, and I will sell you Joseph’s horses.’ The white man returns to me and says, ‘Joseph, I have bought your horses and you must let me have them.’ If we sold our lands to the government, this is the way they were bought. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, November 1876.

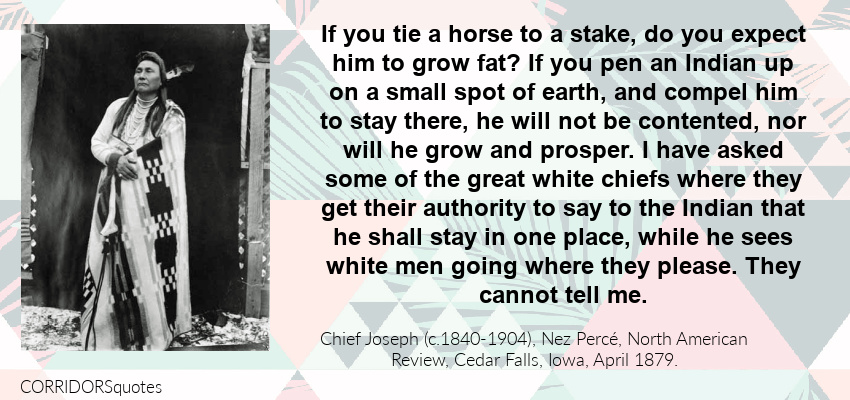

If you tie a horse to a stake, do you expect him to grow fat? If you pen an Indian up on a small spot of earth, and compel him to stay there, he will not be contented, nor will he grow and prosper. I have asked some of the great white chiefs where they get their authority to say to the Indian that he shall stay in one place, while he sees white men going where they please. They cannot tell me. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, North American Review, Cedar Falls, Iowa, April 1879.

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed…The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men are dead. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, 1877.

It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food, no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, 1877.

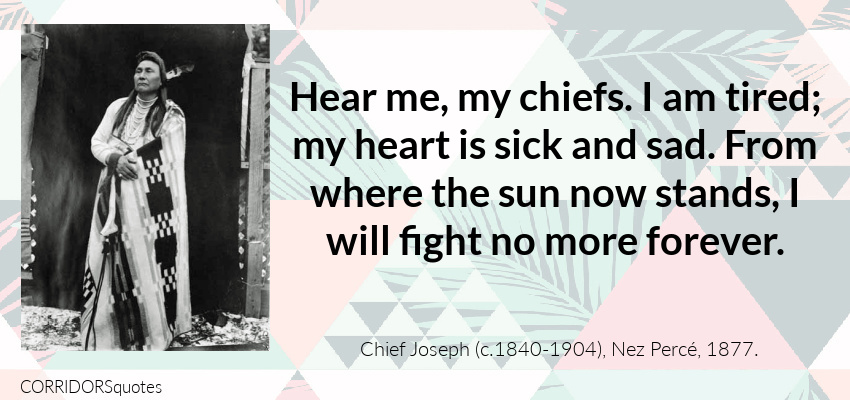

I want to have time to look for my children and see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever. Chief Joseph (c.1840-1904), Nez Percé, 1877.