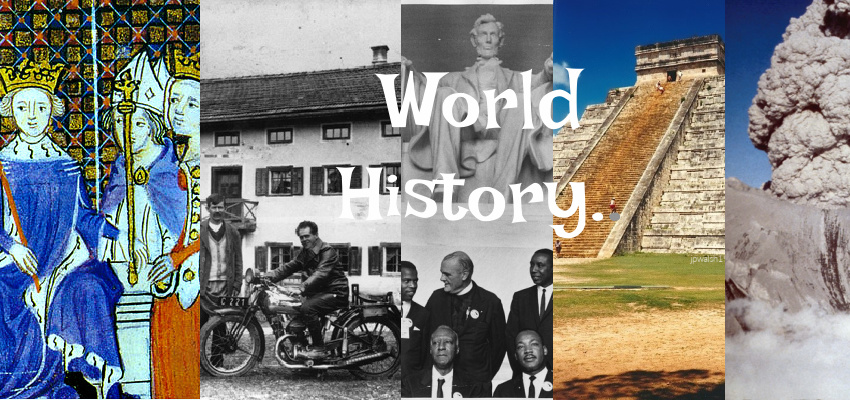

FEATURE image: Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Leaders of the march posing in front of the statue of Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Memorial.) by Rowland Scherman (b. 1937), for the U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. Public Domain/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

By John P. Walsh

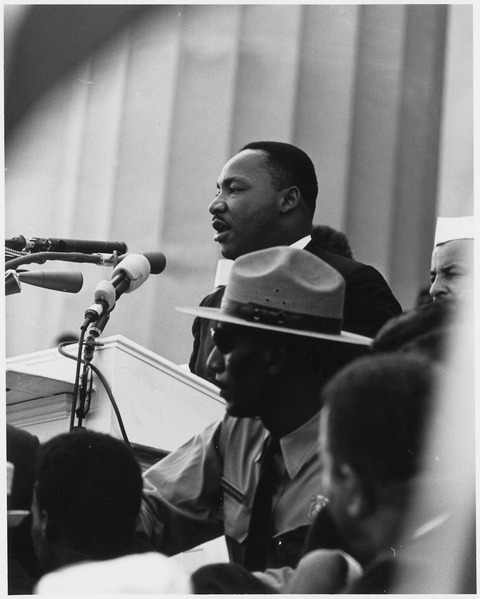

President John F. Kennedy watched the march—and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech—from the White House on television.

Both Kennedy and King were young men—King was 34 years old, Kennedy was 46 years old. Mature beyond their years, each American proffered green oak in some ways—Kennedy was especially more personally sensitive than his “cool” public persona belied him to be. King, too, was mostly uncomfortable on August 28, 1963 with the particular attention, from the media and others, that he was receiving for his remarks at the Lincoln Memorial.

As the civil rights leaders filed into the Cabinet Room at the White House the first thing Kennedy said when he took King’s hand was “I have a dream…” The president was repeating King’s line that immediately impressed him and the nation when they heard it on TV live only a short time before.

King deflected the president’s compliment and immediately asked him what the president thought of United Automobile Workers president Walter Reuther’s excellent speech. It had included a criticism of Kennedy for defending freedom around the world but not always at home. Kennedy replied to King: “Oh, I’ve heard [Walter] plenty of times.”

King and Kennedy hardly talked any more during the visit, though when they did it led to an outcome for action.

Kennedy and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins talked at length about strengthening the civil rights bill following that day’s completely peaceful march. King moved away from the president and down the line to near then-23-year-old John Lewis, head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

One section to the civil rights bill these activists wanted the president to add was a ban on employment exclusion based on race.

As White House and other photographers filmed and snapped pictures of the historic White House meeting of leading progressive personalities of the early 1960s, the civil rights leaders told the president about the accelerating automation in the job market that would potentially depress the availability of jobs.

They also discussed the plight of the inner city, telling Kennedy that Black teenagers were dropping out of school in epidemic numbers. A. Philip Randolph told the president that the entire current generation of young Blacks “had no faith” in whites. They also dismissed Black leadership, government and God. To these young Americans, U.S. society as it was presently constituted meant nothing to them but despair.

During the visit, Kennedy was lobbied to re-insert into the act a section that was stripped in 1957 giving authority to the Attorney General to investigate and initiate lawsuits on behalf of blatant civil rights infringements.

President Kennedy responded that with Robert Kennedy, his Attorney General, he had looked into joblessness and the school drop-out rate among Blacks in Chicago and New York City. At the August 28, 1963 meeting Kennedy encouraged the civil rights leaders to have the Black community do more.

“It seems to me,” the president said, “with all the influence that all you gentleman have in the Negro community that we could emphasize…educating [your]children, on making them study, making them stay in school and all the rest.”

Any add-ons now to the civil rights bill joined existing legislation that was already on the brink of defeat in the Democrat-controlled Senate and too close to call in a Democrat-controlled House.

Despite these close margins, Wilkins countered that the Speaker of the House had assured him that an even stronger civil rights bill could pass the House and would work to pressure the Senate to act. Wilkins suggested that the president go over the heads of the Congress who obstructed passage of the bill and lead a crusade to win voter approval for the civil rights measures.

Kennedy replied frankly to the leaders that civil rights must be a bipartisan effort. For a Democrat president to lead a crusade would allow Republicans to support civil rights and blame the Democrats for it which would hurt the Democratic Party in the South. Kennedy assured the civil rights leaders that “treacherous” political games were being played in the Federal legislature on the bill by both Republicans and Democrats.

Kennedy was countered again – this time by Walter Reuther.

“Look, you can’t escape this problem,“ the white labor leader said, “and there are two ways of resolving it—either by reason or riots. But now the civil war is not gonna be fought at Gettysburg, it’s gonna be fought in your backyard, in your plant, where your kids are growing up.” Reuther further told JFK he didn’t much like the young president’s “seminar” style of governing where “you call a big meeting…and nothing happens.” Reuther told Kennedy that he preferred his vice-president’s governing style where Lyndon B. Johnson “jawbone[d]” an issue until he would “get difficult things done.”

King stayed silent for most of this back and forth debate. When King finally spoke he asked JFK that if the sitting president led a crusade then perhaps his predecessor, Republican president Dwight D. Eisenhower, might get involved. It would then, King suggested, become the bipartisan push Kennedy was looking for.

Kennedy snapped back at King: “No, it won’t.”

In reply, King made a knowing joke: “Doesn’t [President Eisenhower] happen to be in the other denomination?”

Ike’s personal pastor was Rev. Eugene Blake who was in the Cabinet Room. Blake, a powerful force and no pushover, had been the march’s only white speaker.

One reason that Rev. Blake spoke at the march was that he had been arrested in a civil rights demonstration in Baltimore and had gone to jail.

Just hours earlier, Rev. Blake orated: “We come late, late we come, in the reconciling and repentant spirit.” The Protestant clergyman embraced the march’s agenda of civil and economic rights for African Americans and the end to racism. Still, Blake rejected words like “revolution” and “the masses” used by some civil rights activists.

At that day’s White House visit, Blake told Kennedy that Ike could be approached about civil rights. The president pivoted and urged Blake to visit the former president at his home in Gettysburg to discover any political role Ike might be willing to take for the civil rights bill. Kennedy advised: “And include a Catholic and maybe a businessman or two.”

Then pointing to Reuther, Kennedy lightly said: “And leave Walter in the background.” Amid chuckles, Kennedy then left the room of civil rights leaders. Before exiting, the president turned to assure them he would keep in touch on the civil rights bill in the months ahead.

SOURCES:

TAYLOR BRANCH, PARTING THE WATERS AMERICA IN THE KING YEARS 1954-1963. NEW YORK: SIMON & SCHUSTER, 1988.

DAVID GARROW, BEARING THE CROSS: MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND THE SOUTHERN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE, WILLIAM MORROW AND COMPANY, 1986.

OTHER VOICES AT THE MARCH:

Harry Belafonte (1927-2023) was born in New York City died there at 96 years old. Harry Belafonte won a Tony, an Emmy, and 3 Grammy Awards in his career as a film actor and singer that stretched over 70 years. Belafonte was also a civil rights activist who brought and introduced a rafter of Hollywood A-list entertainers to the March On Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963 where Dr. King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Among the more than 200-250,000 attendees at the march were these Hollywood stars. Belafonte chartered a plane from Los Angeles for the historic event to show their support for what was going on in the civil rights movement in America. The great march filled the VIP section at the Lincoln Memorial and the National Mall to past the Washington Monument, a distance of almost one mile. The mood of this massive crowd was one of hopeful jubilation. Afterwards, Dr. King and other civil rights leaders went to the White House to meet with President Kennedy. There they talked about the march, and discussed what was ahead in terms of social conditions and the civil rights movement, including the legislative effort that led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 following Kennedy’s death. Some of the artists and film stars at the Lincoln Memorial that day in addition to Harry Belafonte were Marlon Brando, Rita Moreno, James Garner, Tony Franciosa, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joanne Woodward, Paul Newman, Susan Strasberg, Burt Lancaster, Robert Ryan, Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, James Baldwin, Lena Horne, Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, Charlton Heston and several more.

REMARKS BY HARRY BELAFONTE: “We are here to bear witness to what we know. We know that this country, America, to which we are committed, and which we love, aspires to become that country in which all men are free. We also know that freedom is not license. Everyone in a democracy ought to be free to vote. But no one has the license to oppress or demoralize another. We also know or we would not be here, that the American negro has endured for many generations in this country which he helped to build the most intolerable injustices. To be a negro in this country means several unpleasant things. In the Deep South it often means he is prevented from exercising his right to vote by all manner of intimidation up to and including death. This fact of intimidation is a great weight in the life of any negro and though it varies in degree it never varies in intent which is simply to limit, to demoralize and to keep in subservient status more than 20 million negro people. We are here, therefore, to protest this evil and make known our resolve to do everything we can possibly do to bring it to an end. As artists and as human beings we rejoice in the knowledge that human experience has no color and that excellence in any endeavor is the fruit of individual labor and love. We believe artists have a valuable function in any society since it is the artists who reveal society to itself. But any society that ceases to respect the human aspirations of all its citizens courts political chaos and artistic sterility. We need the energies of these people to whom we have for so long denied full humanity. We need their vigor, their joy, the authority which their pain has brought them and cutting ourselves off from them then we are punishing and diminishing ourselves. As long as we do so our society is in great danger. Our growth as artists is severely menaced and no American can boast of freedom since he cannot be considered an example of it. We are here then in an attempt to strike the chains of the ex-master no less than the ex-slave and to invest with reality that deep and universal longing which has sometimes been called the American Dream.”

PHOTO CREDITS:

Hundreds of thousands descended on Washington, D.C.’s, Lincoln Memorial Aug. 28, 1963. Public Domain/U.S. Government Photo.

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Leaders of the march posing in front of the statue of Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln Memorial.) by Rowland Scherman (b. 1937), for the U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. Public Domain/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking from the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington by Rowland Scherman (b. 1937), for the U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. Public Domain/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Aerial view of Washington Monument showing marchers.) U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. Public Domain/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Leaders of the march leading marchers down the street. U.S. Information Agency. Press and Publications Service. Public Domain/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.