FEATURE image: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Swing, 1876, oil on canvas, 36 1/2 x 28 1/2 inches. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

By John P. Walsh

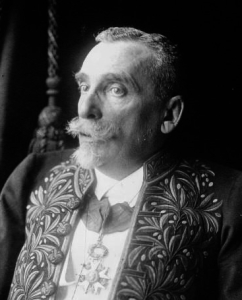

Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) exhibited together in the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1876 and became lifelong friends. Just two years later, in 1878, Caillebotte appointed Renoir to be executor of his will. Now in the wake of Caillebotte’s death in 1894, Renoir and Martial Caillebotte (1853-1910), the artist’s younger brother, were resolved to carry out Caillebotte’s final wishes to the letter. The most important charge given to Caillebotte’s advocates was to persuade the French State to accept their late friend’s collection of Impressionist art that came to be known as the “Caillebotte Bequest.” These 68 paintings were the wealthy artist’s assemblage of prime Impressionist art which today provides a glittering foundation for museum collections around the world, especially the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. An exact count of the bequest varies whether based on the inventories by the estate in 1894, by art writer Gustave Geffroy (1855-1926) also in 1894 or by Renoir, Martial Caillebotte and Léonce Bénédite (1859-1925) in 1896.

In 1894 Caillebotte’s bequest included paintings by living artists such as Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Alfred Sisley, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Two artists in the collection were already dead – and both Jean Millet (1814-1875) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883) were more highly prized than the others at the time. A vast majority of Caillebotte’s more than five dozen paintings were painted and purchased before 1880.

The French government was accustomed to selecting and purchasing works for the national collection on their own initiative and looked on Caillebotte’s donation as a “tricky business” as expressed by Republican Henry Roujon, Fine Arts administrator who had only recently worked for Jules Ferry. From a wanting-to-oblige Establishment viewpoint the bequest was complicated because Caillebotte boldly stipulated that all 68 works be accepted together and earmarked as a group for entrance into the Louvre. Up to now the French State only had experience in purchasing Sisley and Renoir (“Young Girls at the Piano,” acquired in 1892) for the national collection. Moreover the acceptance of Caillebotte’s collection would change State policy to exhibit no more than three works by any artist for Caillebotte’s bequest included more paintings than that number for each artist. Although twenty years had passed since the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874, the French State had never taken much of a public interest in this diverse group of nonacademic artists. On the other side of the table as Renoir and Martial Caillebotte were primarily concerned with the State’s acceptance of the entire body of work, those living artists in the bequested collection had their concerns if they succeeded.

One antidote to this attitude of entrenchment was that the Republican French state in 1894 was halfway into its second decade of shepherding progressive policies onto France and its cultural leaders realized this must extend to a determined national support for this windfall of abstruse avant-garde artists. Following a year of negotiation with executors Renoir and the younger Caillebotte the State cut its deal. They might have refused the whole lot of them, but accepted a majority of the bequest and more than one painting of each artist. Further they formally agreed to exhibit all 40 works and they were duly hung in the Musée du Luxembourg in February 1897. In addition to two by Millet, these 38 Impressionist masterworks are today in the Musée D’Orsay. None of Caillebotte’s own paintings were included in the legacy. Protests by traditional art voices were now useless: the Impressionists, accused of “ruining young artists,” were now on national museum walls. Cézanne’s response to the inclusion of two of his paintings is forthright: “Now (William-Adolphe) Bouguereau can go to hell!” During this hard-edged contest to determine which artists and art works were included or excluded, it was not the museums that picked up the pieces but the mainly French and American collectors as well as the gallery dealers who mounted historic one-man shows for Caillebotte (at Durand-Ruel in June 1894), for Cézanne (at Ambroise Vollard in 1895) and for Monet (Durand-Ruel in May 1895).

The settlement accepted in January 1895 and promulgated a year later was not the last word for Renoir who continued to try to fully achieve his friend’s terms. On at least two occasions – in 1904 and 1908 – the works refused by the State in 1894 were proffered to them. Both times these 28 remaining works were refused and as far as the French State was concerned the case of the Caillebotte Bequest was closed. Only by his death in 1919 were Renoir’s efforts to honor Caillebotte’s bequest to France halted (Martial had died in 1910). In 1928, over thirty years after Caillebotte’s death and bequest, the French State dared to make a legal claim to those remaining 28 works they had rejected three times previously. Inexorably cloaked in superiority, this latest endeavor of the official art establishment revealed its opportunism as the changing winds of taste now clearly favored Impressionism. Both original executors of Caillbotte’s bequest now dead, it was left to Martial Caillebotte’s son’s widow to respond to these highly-placed administrative scratchings. Her decision: she refused to hand over these works and placed them on the open market. The “rejected” and overlooked works of the “Caillebotte Bequest” were sold to private collectors all over the world, including to Americans Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951), and H.O. Havemeyer (1847-1907) and Louisine Havemeyer (1855-1929). Many of these remainder works’ locations are unknown.

SOURCES: Anne Distel, Impressionism: the First Collectors, Abrams, 1990; Anne Distel, Douglas W. Druick, Gloria Groom, Rodolphe Rapetti and Kirk Varnedoe, Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 1995; http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/history-of-the-collections/painting.html; http://www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/312.html?page=2