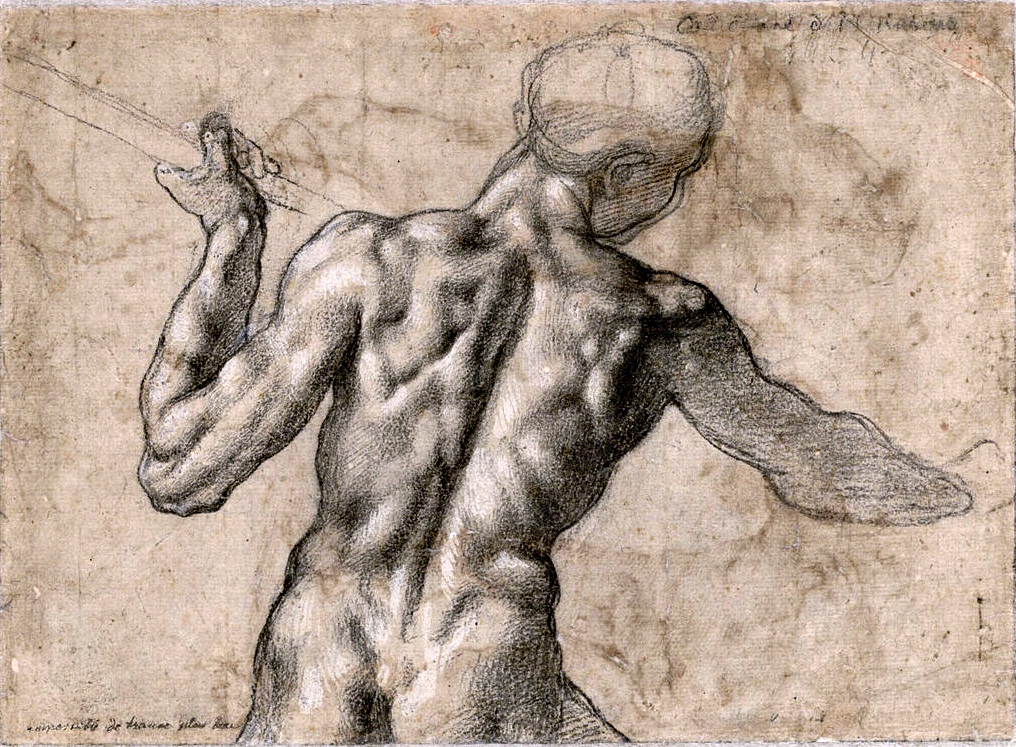

FEATURE image: Peter Paul Rubens, Copy of Leonardo’s Battle of the Standard (from the Battle of Anghiari), 1603, Louvre.

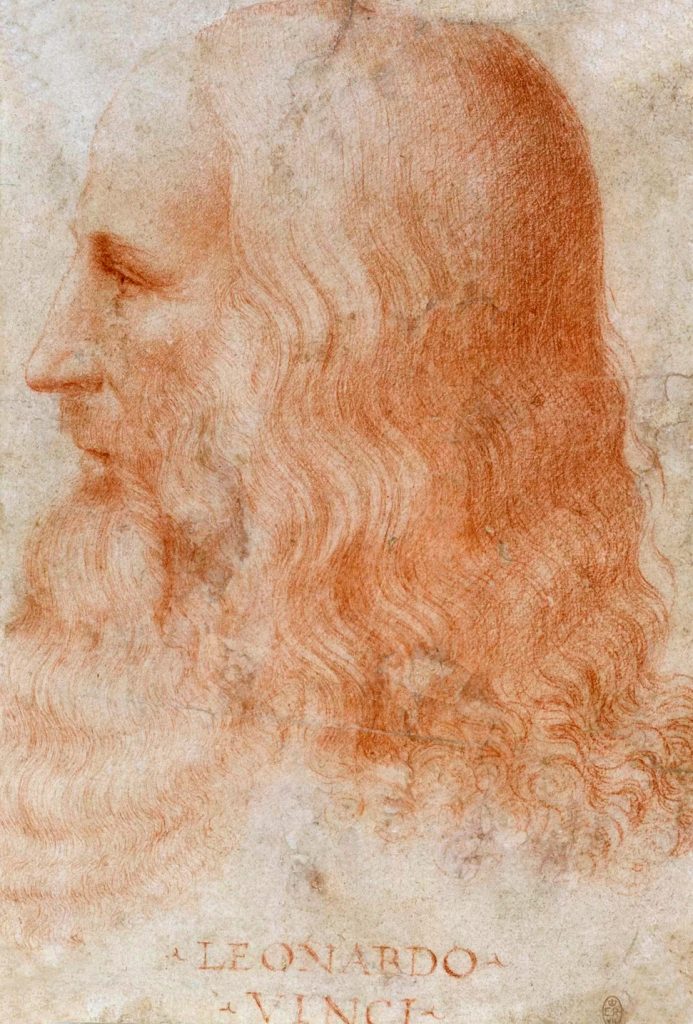

On May 2, 2019, the world remembered the day 500 years ago when Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Italian Renaissance artist and polymath, died. The 67-year-old applied the spheres of the human brain to its many branches of knowledge and voraciously fused his interests and studies into one lifetime that inspired universal learning in Europe.

Leonardo da Vinci made original contributions as an inventor, draftsman, painter, sculptor, architect, scientist, musician, mathematician, engineer, writer, anatomist, geologist, astronomer, botanist, paleontologist and cartographer.1 Leonardo was involved in military science, hydraulics, aerodynamics, and optics. Used by princes and admired by kings, charming and handsome Leonardo da Vinci could show in his notebooks that he was often misanthropic.2 A significant part of his important visionary achievements is that Leonardo da Vinci painted two of the most reproduced artistic masterpieces of all time: the Mona Lisa (1503, Louvre, Paris) and The Last Supper (1490s, Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan). Leonardo, after a lifetime of adventure, curiosity, and solid achievement died in Amboise, France, following a short illness.

In 1516 Leonardo left Italy for the first time to live in France under the protection of its most cultured young French king, François I (1494-1547). As a dedicated artist, Leonardo experienced a lifetime of disappointment from most of his would-be patrons starting with his father through to Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Magnificent (1449-1492), hapless Milanese duke Ludovico Sforza (1452-1508), Milanese governor Charles II d’Amboise (1473-1511), and Lorenzo’s son and a papal brother, Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici (1479-1516), among others. As Leonardo was ahead of his times it can be said that only at the end of the artist’s life—in 1516, under the wing of François I—that the bulk of his times, that is, the temporarily powerful men in them, had failed him and mankind’s enduring greatness. François I was Leonardo’s first unconditional patron3—while the rest, relatively speaking, are history’s minor players.

At Leonardo’s death his reputation as an artist and man rested, as Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) relates, on his physical strength, generosity, and artistic innovations which brought art and society out of its reliance on the past and its well-intentioned model books into a future of science and art which characterized the best of the Renaissance period. Because of Leonardo’s lifetime of study and work, mostly in isolation from a majority of his fellow artists’ and other practitioners’ careers, he bore the fruit of innovation, including new and creative forms and motifs for art. These emanated out of the imagination of the individual artist who closely observed the workings of nature. Leonardo’s artistic innovations included the subtle skill of sfumato (shadowing) and, as a draughtsman, progressive chalk and cross-hatching techniques. These inspired other great artists, like Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), and only begins to account for the knowledge Leonardo gained from the physical sciences, particularly anatomy.

Leonardo spent his final three years in Italy in the Vatican (1513-1516), effectively a refuge from petty Italian tyrants. He departed for France in 1516 under the protection of its warrior and cultured 21-year-old new king, François I, whom 64-year-old Leonardo first met in late 15154. Like his cousin and father-in-law predecessor King Louis XII of France (1462-1515) and his cultured mother Louise de Savoie (1476-1531), François I worked hard to recruit the Italian High Renaissance’s most inventive artist for the Gallic Kingdom. When Leonardo finally crossed the Alps he carried with him his recent paintings of the Mona Lisa, Saint John the Baptist, and the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne—all works in the Louvre in Paris today.5 In the second edition of Vasari’s Lives of the Artists6 he described Leonardo in his last months of life in France. In 1519, after a happy period in France at the Château de Cloux, Leonardo was a sick and bedridden man. At the very end, Vasari writes, Leonardo “could not stand [and had to be] supported by his friends and servants.”7. The King paid Leonardo “affectionate visits” in these last days. Vasari intimates that the dying artist consciously felt himself honored to be ministered to by François I Vasari and that Leonardo realized the distinct privilege to “[breathe] his last in [the king’s] arms.”8 This death bed scene, particularly Vasari’s tender detail, has been subsequently imagined in the artwork of artists, including Ingres’ famous painting dated 1818 in the collection of the Petit Palais in Paris.

The mother of François I, Louise de Savoie (above), worked hard to convince Leonardo to leave Italy for France.

Leonardo carried with him over the Alps to France three of his recent paintings (above) – Mona Lisa (1503), Saint John the Baptist (1513), and the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1503). All are in the Louvre today.

Ink consecrated to the artistry of Leonardo da Vinci is vast. The Bible-like exhibition catalog for Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman from the 2003 show at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is a 786-page testament. That tome presents and discusses about 100 drawings by the master. This article focuses on one image – Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, particularly its central section called the Battle of The Standard.

In October 1503 Leonardo’s commission by the Florentine Republic was to commemorate the military victory of the Florentines over the Milanese in 1440. It would be one of the major artworks in the newly-built Sala de Gran Consiglio (Grand Council Hall) by IL Cronaca (“The Chronicler”) to the rear of the Palazzo della Signoria, also known as the Palazzo Vecchio.9 The commission was given to Leonardo by Republican standard-bearer Piero Soderini (1450-1522) with one of Leonardo’s contracts signed by Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527)—and so entered into the annals of what became a fabled art competition (“concorrenza”).

Ink consecrated to Leonardo da Vinci’s art is vast.

Statesman Piero Soderini of the Florentine Republic awarded Leonardo the mural commission for the Battle of Anghiari in October 1503.

In the process of re-decorating this room with its coffered ceiling and walls with paintings of battle scenes dedicated to the exaltation of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Leonardo da Vinci’s innovative fresco of the Battle of Anghiari was lost or destroyed.

Peter Paul Rubens’ copy of 1603 of the lost Battle for the Standard, the central section of the Battle of Anghiari fresco by Leonardo, 1503-06, in Palazzo della Signoria (also, Palazzo Vecchio) in Florence. While Rubens’ copy is the best known, there are copies of Leonardo’s work by other 16th century artists.

In 1503 Leonardo da Vinci was at the height of his artistic powers. The Battle of Anghiari was a commission for a large scale, complex and dramatic fresco mural on one wall of the Sala de Gran Consiglio in Florence during the short-lived restored Republic (c.1492-1512). Leonardo looked to paint the fresco in dazzling oils and glazes but his complicated experimental techniques to adhere the pigment to the wall largely failed.10 With the fresco’s ultimate destruction in the early 1560’s under Vasari who redecorated the Great Council Hall with six of his own massive battle scenes, he and his Medici rulers were faced with another of Leonardo’s deteriorating frescos similar to the disastrous flaking of The Last Supper in Milan. The Battle of Anghiari was not in an obscure monastery refectory but the central hall of changing political power in Florence.11

Leonardo’s Last Supper fresco in Milan started flaking almost as soon as it was painted in the 1490’s. Leonardo’s experimental painting techniques for that project had largely failed.

Fragmentary remains by Leonardo of his Florentine project are his preparatory drawings whose subjects include horses, riders, and combatants on the battlefield in various stages of creative development. Some of these drawings were made by Leonardo immediately upon receiving his commission in late 1503.12 Several copies and copies of copies made by other artists also survive. While the preparatory drawings do not complete the full composition— though contemporary written sources lend credence to books of sketches that are lost13—Leonardo possibly did not even complete a cartoon before he started painting on the wall.14 While copies by others intrigue, they are problematic to envision Leonardo’s final fresco of the Battle of Anghiari—yet each of these sources provide insights.

The Battle of Anghiari is arguably Leonardo’s most important public commission.15 It manifested itself in the context of impactful local history, civic pride, city government, and the artist’s own vision and skills in its employ. Florence was Leonardo’s native city and he wanted to make a strong impression. Sixty years after Leonardo left his brilliant fresco on the west wall.16 Vasari, whose redecoration of the Palazzo Vecchio included a fresco cycle of his own almost certainly covered over all or part of Leonardo’s unfinished fresco. A desire for new artwork to showcase the Medici restoration under Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574) naturally extended to the Grand Council Hall. The late-fifteenth-century Republic had commissioned Leonard’s battle fresco—and that form of government had ended in Florence in 1512.

Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519 -1574) ruled Florence from 1537 until his death.

As Vasari relates in his Lives of the Artists, Leonardo depicted a scene from the life of Niccolò Piccinino (1386-1444), an Italian mercenary officer or “condottiere” in the service of the politically brilliant and physically repulsive duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti (1392-1447). Fighting for Milan, Piccinino—aided by two score of cavalry squadron, many foot soldiers17and treacherous Florentine exiles—was defeated by a force led by the Republic of Florence under Francesco I Sforza (1401-1466). The victory at the Battle of Anghiari on June 29, 1440 handed the Florentines domination of central Italy. At the turn of the sixteenth century the new republic of Florence continued to face warring tyrants as neighbors including Cesare Borgia (1475-1507). At the start of a new century and Republic the timing was ripe to depict in its government hall valorous Florentine warriors defeating political enemies. In 1503, Florentine officials gave Leonardo an in-depth orientation of the 1440 battle using historical texts but the artist brushed these aside as he conceived the scene to be depicted, a virtually cinematic induction of the battle’s climax —the mortal contest by the Florentines to capture the standard from the Milanese. Leonardo’s first sketches for it are of a condensed melée full of the swirling movement and stirring sensations of battle.18 The actual standards taken during the battle had been kept in the Grand Council Hall as a trophy.19

Niccolò Piccinino. Defeated at the Battle of Anghiari, the Italian mercenary becomes the central protagonist of Leonardo’s fresco.

Local battles such as the Battle of Anghiari were usually part of larger campaigns— in this instance, The Lombardy Wars of 1423-1454— and fought by hired warriors. Mercenaries usually provided terms to competing foes that protected the mercenary’s best interest. Following the Battle of Anghiari, Piccinino, who had been captured, was soon after released. In the next battle at Martinengo, he defeated and captured Sforza. Because of these endless war games, Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) advised in The Prince that a ruler should not be tempted to use these swords for hire – and cited Francesco Sforza by example.20

Machiavelli, author of The Prince, signed an order to commission Leonardo to create the fresco commemorating the Battle of Anghiari for Florence’s newly-built Sala de Gran Consiglio (Grand Council Hall).

Cosimo I de’ Medici who ruled Florence starting in 1547 was interested in that which supports power— including art. Vasari’s new paintings of Cosimo I de’ Medici’s wartime exploits was partly a political act. By ridding the hall of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari — a Republican military victory from long ago — Vasari worked his political masters’ desires. The ultimate reasons and fate of Leonardo’s artwork is not known but if Vasari destroyed the mural he would not be the first Italian artist to destroy a competitor’s artwork as shall be seen.

In late 1503 Leonardo, installed in a temporary workshop at Santa Maria Novella, about a fifteen-minute walk to the Palazzo, was given a deadline for the mural’s completion of February 1505. Like the fabled competition between Leonardo and Michelangelo that was intentionally arranged by Florence’s political operatives, the deadline for completion was also a demand for Leonardo’s art outside the artist’s concerns. The first late winter deadline passed as did those in spring and summer. Setbacks included Leonardo’s meticulously slow work, other projects he took up that kept him away from the fresco, and even bad weather.21

Leonardo’s designated workshop for the mural commission was the Dominican church built in 1420, Santa Maria Novella.

In early 1504 the wall painting of the Battle of Anghiari and its 51-year-old artist was joined by Michelangelo Buonarroti who would paint his Battle of Cascina in the same room and possibly on the same wall. Michelangelo, recently turned 28 years old, would depict the Florentine military victory over Pisa in 1364. Neither this imposed rivalry or proximity encouraged their friendship.22 Michelangelo was intense, pious, and unwashed contrasting to Leonardo’s genial, independent, and stylish manner.23 However, their professional relationship temporarily influenced each other’s artmaking.

In 1504 and 1505, Michelangelo learned to use Leonardo’s innovative stylus cross-hatching technique along with the chalk technique that Leonardo was continuing to exploit in the Battle of Anghiari. Inspired by Michelangelo, Leonardo did masterful drawings of nude figures though he did not use them. In Michelangelo’s preparatory drawings for the Battle of Cascina—that and copies by others are what survive of the project– the younger artist used Leonardo’s cross hatching technique for the pull of the skin. He experimented with Leonardo’s chalk technique to display types and degrees of muscular tension on figures.24 Yet, according to Vasari, the two clashed at almost every turn. Michelangelo’s use of Leonardo’s advanced techniques was restricted to the short period of their common commission and Leonardo openly disparaged Michelangelo’s cartoon of male nude bathers as coldly analytical.25

Two Michelangelo chalk studies. Above: Life Study for a bathing soldier in the lost cartoon for the Battle of Cascina, black chalk, 404 x 258 cm, Teylers Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands. Below: Male back with a flag.

Leonardo da Vinci, Anatomical Studies of the Nude, connected with the Battle of Anghiari, c. 1504, Royal Library, Windsor. Though influenced by Michelangelo’s nude drawings in this time, Leonardo’s design and imagery for his battle scene looked to invention and unexpected drama rather than the nude.

In spring 1505 Michelangelo’s cartoon was finished but his painting barely started—and the younger artist left Florence for Rome. Michelangelo accepted the commission to build the tomb of Pope Julius II (1443-1513) although it would not be completed until 1545 and on a much-reduced scale. He returned to Florence the following spring but was soon back in Rome to paint, between 1508 and 1512, the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In 1506 Leonardo’s gradual departure for Milan, complete by 1508, began. Leonardo stayed in Milan until 1513 when he was invited by the pope to the Vatican. Leonardo and Michelangelo had in Florence shared a common commission from the Republic. Their two battle scenes presented, each in their own way, a tangle of intertwined figures. Otherwise, each artist created compositions of varying subject matter and style which proved seminal for art-making schools of the future. Leonardo’s swirling horsemen in the Battle of Anghiari inspired the Baroque style and Michelangelo’s bathers in the Battle of Cascina displayed a perfect template for Classicism. These two great artists also shared, despite their age difference or varying temperaments, the fact that neither of them completed their commissioned work.

Michelangelo’s David had just been placed Florence’s central square when the painting competition (“concorrenza“) between himself and Leonardo da Vinci began. Leonardo had served on his native city’s committee which decided where to place Michelangelo’s 17-foot tall marble sculpture. Today a copy stands outside the Palazzo Vecchio.

At the time of the public commission in Florence, Leonardo had just finished his Mona Lisa (1503, Louvre, Paris) and Michelangelo had just installed, in the city square, his David (1501-1504, Accademia Gallery Museum, Florence). Leonardo had been part of the city committee to recommend where Michelangelo’s David should be placed.26 Over the next decade, until 1512, Leonardo’s and Michelangelo’s unfinished wall paintings—that they both had abandoned (a worthy reason for a later Medici to paint it over)—adorned the same room possibly side by side. Michelangelo’s work was mutilated first with the fall of the Republic. Young artists had flocked to study and copy these unfinished artworks, including a young Raphael.27 In 1512 one of these artists, a 24-year-old named Bartolommeo Bandinelli (1488-1560)—he had been obsessive in studying Michelangelo’s cartoon to the point of sneaking in to the Council Hall at night—in one moment grabbed the cartoon and cut it into pieces. The motivation for Bandinelli’s destruction is unclear. The center section of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari – namely, Battle of the Standard– remained intact on the wall and for decades saw copies and written descriptions made of it. After 1508, neither Michelangelo nor Leonardo were anywhere near Florence as both moved on to larger opportunities.28

Leonardo openly disparaged Michelangelo’s cartoon of male nude bathers as coldly analytical. Younger artists preferred the noble and expressive form of Michelangelo’s nudes to Leonardo’s messier constructions.

Focusing on Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, and, particularly, the Battle of the Standard, its central panel, one is impressed by Leonardo’s revolutionary approach to drawing. Leonardo shattered tradition, specifically in drawing. First, Leonardo was not tidy in his drawing. Medieval tradition was fundamentally concerned with conserving the controlled line. A draftsman’s artistic ability was judged by patrons and cultural tastemakers by the accurate lines he created directly out of an existing model-book. Leonardo’s early silverpoint drawing of a Bust of a Warrior in the British Museum demonstrates his ability to masterfully fulfill this Renaissance expectation.29 As Leonardo the artist developed, by the end of the fifteenth century he was attacking this long-held linear tradition in his notebooks as a failed technique.30 The fiery scribbling of Leonardo’s drawing style expresses his process of creative exploration but equally his rebellion towards the old technique. In its place, Leonardo shows himself in his drawings to be actively pushing outside the linear restraint of quattrocento drawing and formulating a new artistic standard derived from orientation to the model. As an avant-garde artist in this mode Leonardo practiced it alone for 25 years.31 The profligacy of his drawings – often multiple images on the same page of paper expressing his changing primo pensiero (“first thoughts”) – indicates the brilliancy of Leonardo’s creativity. His drawing technique points to the artist seeking to free the immaginativa to emphasize dramatic invention that included individual details (such as heads) and unto an entire scene. Leonardo’s artistic practice worked to overturn, or revolutionize, the tradition-bound formulas imposed on art. He replaced it with a new and radical conception of nature ever-changing as the drawing framework.

Vasari goes into admirable detail on Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari in his Lives of the Artists in editions of 1550 and 1568. That Vasari destroyed or painted over this same work by Leonardo around the same time during a re-decoration of Florence’s Grand Council Hall is difficult to reconcile with his writings.

Invested Quattrocento cultural taste-makers and practitioners found danger in Leonardo’s new artistic direction. Art producers and patrons could not understand why a single artist for his own personal exploration would forsake generations of practiced skill and systematics. The challenge for Leonardo after he discarded the model-book was difficult and clear– to invent figures and forms to replace it. This monumental task helps explain some of the artist’s motivation for working in many areas such as anatomy, mechanics, botany, and geophysics. Wide study was certainly owing to Leonardo’s “unquenchable curiosity”32 but its practical application worked to fulfill his ambition to locate source material to replace the model-book’s groupings, movements, and forms that he had audaciously sacked. The culmination of his approach is manifest in the Battle of Anghiari. To discover some of Leonardo’s unfolding revolutionary creative process makes this artwork exciting to consider as Vasari describes it in detail in his Lives:

“The great achievements of this inspired artist so increased his prestige that everyone who loved art, or rather every single person in Florence, was anxious for him to leave the city some memorial; and it was being proposed everywhere that Leonardo should be commissioned to do some great and notable work which would enable the state to be honored and adorned by his discerning talent, grace, and judgement. As it happened the great hall of the council was being constructed under the architectural direction of Giuliano Sangallo, Simone Pollaiuolo (known as Cronaca), Michelangelo Buonarroti and Baccio d’ Agnolo, as I shall relate at greater length in the right place. It was finished in a hurry, after the head of the government and the chief citizens had conferred together, it was publicly announced that a splendid painting would be commissioned from Leonardo. And then he was asked by Piero Soderini, the Gonfalonier of Justice, to do a decorative painting for the council hall. As a start, therefore, Leonardo began work in the Hall of the Pope, in Santa Maria Novella, on a cartoon illustrating an incident in the life of Niccolò Piccinino, a commander of Duke Filippo of Milan. He showed a group of horsemen fighting for a standard, in a drawing which was regarded as very fine and successful because of the wonderful ideas he expressed in his interpretation of the battle. In the drawing, rage, fury, and vindictiveness are displayed both by the men and by the horses, two of which with their forelegs interlocked are battling with their teeth no less fiercely than their riders are struggling for the standard, the staff of which has been grasped by a soldier who, as he turns and spurs his horse to flight, is trying by the strength of his shoulders to wrest it by force from the hands of four others. Two of them are struggling for it with one hand and attempting with the other to cut the staff with their raised swords; and an old soldier in a red cap roars out as he grips the staff with one hand and with the other raises a scimitar and aims a furious blow to cut off both the hands of those who are gnashing their teeth and ferociously defending their standard. Besides this, on the ground between the legs of the horses there are two figures, foreshortened, shown fighting together; the one on the ground has over him a soldier who has raised his arm as high as possible to plunge his dagger with greater force into the throat of his enemy, who struggles frantically with his arms and legs to escape death.

It is impossible to convey the fine draughtsmanship with which Leonardo depicted the soldiers’ costumes, with their distinctive variations, or the helmet-crests and the other ornaments, not to speak of the incredible mastery that he displayed in the forms and lineaments of the horses which with their bold spirit and muscles and shapely beauty, Leonardo portrayed better than any other artist. It is said that to draw the cartoon Leonardo constructed an ingenious scaffolding that he could raise or lower by drawing it together or extending it. He also conceived the wish to paint the picture in oils, but to do this he mixed such a thick composition for laying on the wall that, as he continued his painting in the hall, it started to run and spoil what had been done, So shortly afterwards he abandoned the work.”33

It seems nearly inconceivable that Vasari could write so appreciably of Leonardo’s fresco and then destroy it. Yet its removal, whether wholly destroyed, or lost by being painted over or misplaced, is a fact. Leonardo who no longer relied on the model-book as his authority the artist answered with his own creative immaginativa and all of the facets of nature. In this revolutionary creative process, Leonardo further anticipated the modern era’s introduction of the psychological component into a drawing. The psychological element that Leonardo introduced extended to the figures Leonardo depicted in drawings but it benefited the individual artist’s ability to think and dream creatively. To this end Leonardo consciously devised mental exercises to produce psychological effects in himself.34

Leonardo anticipated the modern era’s introduction of the psychological component into a drawing.

It is half life size from a live model. Over the years some scholars have doubted its authenticity as a Leonardo drawing.

Verso of Study of a Warrior’s Head for the Battle of Anghiari (above drawing).

This is one of the most famous drawing studies by Leonardo da Vinci for the Battle of Anghiari fresco mural project.

Within wide study in the physical sciences, Leonardo attempted everything̱– and did not always finish. It was the immensity of his study and his loathing of the finished quality of the model-book that allowed Leonardo to abandon projects and pick up new and creative directions and methods. Leonardo’s world view as an artist for his art was universal—indeed, he personified the popular definition of “Renaissance Man.” In his artistic boldness and innovation, Leonardo’s methods and objectives found him its sole practitioner for years—even decades. Yet Leonardo was a man of his times. The era of the mid-to-late fifteenth century was one of social awakening to the globe and its conquest by nations and kingdoms. The historical period saw great changes in cultural perceptions based on European cities achieving charters of economic and political freedom as well as new scientific and other discoveries. These included the heliocentric model of the solar system by astronomer and mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) and the international voyages of discovery by Christopher Columbus (1451-1506). It was an age of revolutionary ideas and technology and Leonardo da Vinci had no doubt it included art.

In Leonardo’s drawings there is the untidy immaginativa quality in its hasty, scribbled animations. Studies for the Battle of Anghiari present a cacophony of images—drapery studies; grotesque heads; armory; horses. For each area, Leonardo’s drawing between 1503 and 1506 had reached mature stylistic development.35 Not since Leonardo’s The Adoration of the Magi in 1482 had he created a composition achieving the cohesion of gestures and inter-relationships among figures.

There are speculatively three panels or sections completed for the Battle of Anghiari. The most recognizable is the large central panel or section known as the Battle for the Standard. It is known by its copies by other artists. Leonardo’s central panel depicts four men, one partially hidden, riding war horses. They are engaged in the heat of combat, frozen in a frame of animated movement, for the capture of a standard during the battle. Other sections of the Battle of Anghiari—derived from Leonardo’s small preparatory sketches—depict a wild, galloping horse and a pair of belligerents on horseback. These are briefly discussed below. The most well-known copy of the central section of Leonardo’s fresco (the only section he apparently painted) is by the great artist Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). In the collection of the Louvre, Rubens’ copy dates from 1603 and is, in fact, a copy of a copy. Rubens copies Lorenzo Zacchia’s (1524-c.1587) copy dating from 1553 which he possibly took directly from the fresco or a lost cartoon. There are three extant copies by other artists of Ruben’s copy of a copy of the possibly original artwork.36 These copies at various removes provide insight into the impact for art through the centuries. The rest of Leonardo’s composition is conjectured based on drawings.37 The left panel or section Leonardo could have intended to be horsemen charging into battle while the right panel or section could be the taking of the bridge over the Tiber on horseback which was a key action for victory. The preparatory drawing sheets have images on top and below and may be related as part of a narrative sequence that Leonardo worked to clarify and simplify as a design until he started painting the composition.38 Throughout the project Leonardo had detail and atmospherics in mind though in its piece meal condition today, a full aspect of his creative process is irretrievably lost.39

Horses are one of Leonardo’s favorite subjects. The Battle for the Standard portrays three soldiers on three horses with swords brandished in the smoke and flame of hand-to-hand combat. A fourth soldier on horseback is partially hidden. Two more soldiers have fallen beneath the hooves of their reeling horses and attempt to cover themselves with their shields. The weight of the horses is depicted in their meaty haunches. The horses’ heads are ancient and noble. They crush, bite, and plow into the heat of battle. The screaming head of Niccolò Piccinino –the protagonist of the Battle for the Standard — and from whose hands the standard is wrested away by Florentine soldiers (the profile on his immediate right) wore a large red cap as described by Vasari.40

The overall configuration of the scene is Leonardo’s Renaissance construction of the type of dense figures discovered on ancient Greek and Roman sarcophagi. The stylistic effect of Rubens’ copy of Leonardo’s Battle of the Standard is, by virtue of its similarity, carried forward into the seventeenth century as witnessed by Rubens’ The Hippopotamus Hunt (1616) and The Lion Hunt (1621) both in the Alte Pinakoteck in Munich. The question can be posed: to what degree is Rubens’ stylistic effect, by virtue of his 1603 copy of a 1553 copy of Leonardo’s 1503 image, inferred into Leonardo’s Battle of the Standard? Yet Leonardo’s battle, seen by thousands over decades before its demise, can be said to have directly influenced battle scene depictions whose style continued into the Romantic Period in mid19th century France.41

The screaming head in the background on the left side of the painting is speculatively based on the head of Leonardo’s protagonist in the Battle of the Standard.

Along with these artistic innovations and achievements by Leonardo in a long, lonely process of exploration the hallmark achievement of the Battle of Anghiari is its reckless artistic inspiration. While historical construction of Leonardo’s drawing method requires speculation, existing studies for the work, including those specific to the Battle of Anghiari, provide insights. For instance, Leonardo deployed the pen as well as chalk in preparatory drawings for the Battle of Anghiari. This practice continued the spontaneous and dynamic plasticity of his drawing technique from the 1490s42 and contained psychophysical and temporal effects.43 Up to Leonardo, the general practice for using a pen or stylus was by way of short parallel lines. In the Battle of Anghiari Leonardo is the first Italian artist to systematically use curvilinear hatching.44 A complementary contrast to Leonardo’s inventiveness is that he valued and paid attention to his work experiences. After the early 1480s he retained his sense of form and design and continued to work through particular problems that interested him within a general trend of development.45

The horse drawn from life shows a tense rider pivoting.

Leonardo’s drawings, including his preparatory studies, convey a sensational appearance of continuous movement. Formed into a triangle the figures of combatants in the central section of the Battle of Anghiari and elsewhere move in a swirling motion similar to the apocalyptic liquid cascades Leonardo would later draw. Facial expressions, gnarled and strained on both man and beast, add their distinctive vitality to the animated whole. The Battle of the Standard works similarly to Leonardo’s mechanical drawings in their careful construction. The “machine” operates as an expression of the physicality and emotional and psychological intensity of men fighting to the death. Leonardo, as discussed, based this key scene for the city-state commission on an episode described in historical written texts.46

Leonardo in his first draft of a drawing worked to establish this general sense of movement. In first drafts he attempts the pictorial pitch that he will develop. In the second stage (“per ripruova”) Leonardo begins to create major motifs.47 The two most important primi pensieri for the Battle of Anghiari are pen and ink drawings from the Gallerie dell’ Accademia in Venice, Italy. Scholarship’s quest to reconstruct Leonardo’s creation of the Battle of Anghiari has been identified as “quixotic,”48 yet these drawings while no larger than the size of a clenched fist give out significant clues.

In one of the preparatory drawings the horseman on the left is looking back over the horse’s haunches, a dramatic image among the handful of fighters in close combat that Leonardo will condense into a dominant motif in the Battle of the Standard. The artist’s steady progression belies his reputation as a slow worker though this inventive stage of drawing appealed to him most. For each stage, Leonardo’s drawing is a fully animated artistic expression of his subject matter. While the creative process of Leonardo’s drawing brings the image, as Heinrich Wöfflin observed, to the “verge of the unclear,”49 it also begins to reveal some of the inner workings of Leonardo’s brilliance. In exchange for the free and kinetic character of drawing studies taken to the brink, the later and final work becomes increasingly plastic and compact.50

It is speculated that this preparatory drawing was for the right panel (or section) of the fresco. It depicted the taking of the bridge over the Tiber River that was a key historical action to military victory for the Florentines over the Milanese at the Battle of Anghiari on June 29, 1440.

Anticipating Degas’s racehorses 350 years in the future, this drawing of horsemen charging to battle may represent the left panel (or section) of the Battle of Anghiari that Leonardo envisioned as a three-part narrative sequence.

In the drawings for the Battle of Anghiari he communicates in lively action and engrossing drama the close physical contact of the horses and their riders encircling and falling upon one another in the passion and violence of war.51 The fresco in the Florentine council chambers would remind leaders of war’s brutality and, though a glorification of civic heroism and pride, the wall-sized image served to show the fury of slaughter that military battles cost. The Battle of the Standard was an image that conveyed the phrase that typified the meaning of war for Leonardo: pazzia bestialissima (“beastly madness.”)52 Recalling Bertoldo’s battle scene that originally decorated the Florentine palazzo of Lorenzo de’ Medici (“the Magnificent’) and based on an ancient Roman sarcophagus, proffered to the viewer no identifiable sides. War is not a glorious narrative, but combatants falling into one another. In addition to its classical and Renaissance allusions, its plastic form appealed to Leonardo’s beliefs and attitudes about the intrinsic nature of combat that he then looked to dramatize in the Battle of Anghiari.

Leonardo da Vinci, Study of horses for the Battle of Anghiari. Leonardo depicts horses displaying emotion.

The left-handed hatching is for a drawing taken from a clay or wax model.

The artistic drawings that survive which reveal Leonardo’s artistic process are an invaluable piece of a final enterprise that ultimately failed to materialize on several levels despite Leonardo believing the high-level commission was vital to his reputation as an artist.53 In the end, Leonardo was viewed by the oligarchs as not only procrastinating but having not fulfilled his contract and they sued Leonardo for breach. Yet more enduring than a legal concern was the art project involving Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo Buonarroti. The work accomplished by these two giants of art reverberates through the centuries to today. Theirs is a legacy of the individual artist still being sought out—though by chairmen and presidents rather than popes and princes. A legacy that says artists are no longer craftsmen or tradesmen but artistic personalities in their own right with a unique and appealing style who are thus engaged for their singular brilliance.54 In the face of what was an incomplete, sometimes failed, and ultimately abandoned project—its competitive nature notwithstanding—all the variations of Leonardo’s creative activity funnels into a tremendous example for the mission of the artist –that is, to serve first neither patron nor purse nor artistic reputation —but the glory of making one’s art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Acidini Luchinat, Christina, Butters, Suzanne B., Chiarini, Marco, Cox-Rearick, Janet, Darr, Alan P., Feinberg, Larry J., Giusti, Annamaria, Goldthwaite, Richard A. , Meoni, Lucia, Piacenti, Kirsten Aschengreen, Pizzorusso, Claudio, Testaverde, Anna Maria, The Medici, Michelangelo, And The Art of Late Renaissance Florence, Yale University Press in association with The Detroit Institute of Arts, New Haven and London, 2002.

Ames-Lewis, Francis, Drawing in Early Renaissance Italy, Revised Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, Second Edition, 2000 (originally published 1981).

Ames-Lewis, Francis, The Intellectual Life of the Early Renaissance Artist, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2000.

Bambach, Carmen C., editor, Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2003.

Berenson, Bernard, The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, Phaidon Press, London, 1959.

Braham, Allan, Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century, The National Gallery, London in association with William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd, London, 1985.

Braudel, Fernand, Out of Italy: 1450-1650, trans. Siân Reynolds, Flammarion, Paris, 1991.

Clark, Kenneth, Leonardo da Vinci, Penguin Books, London, 1993 (first printed 1939).

Clark, Kenneth, Selected Drawings from Windsor Castle: Leonardo da Vinci, Phaidon Press, London, 1954.

Durant, Will, The Renaissance: A History of Civilization in Italy from 1304-1576 A.D., Simon and Schuster, New York, 1953.

Gombrich, E. H., Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance, Phaidon Press, London, 1966.

Hartt, Frederick, History of Italian Renaissance Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, Third Edition, 1987.

Hohenstaat, Peter, Leonardo da Vinci, Könemann, Köln, 1998.

Isaacson, Walter, Leonardo da Vinci, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2017.

Machiavelli, Niccolò, trans. William J. Connell, The Prince, Bedford/St. Martin’s, Boston and New York, Second Edition, 2016 (originally published 2005).

Meiss, Millard, The Great Age of Fresco Discoveries, Recoveries and Survivals, George Braziller, Inc. in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1970.

Popham, A.E., The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, Jonathon Cape, London, 1977 (first published 1946

Saviotti, Franco, Florence, Edizione – SAFRA, Firenze, 1981.

Steinberg, Leo, Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper, Zone Books, New York, 2001.

Turner, Jane, editor, Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist Art, Volume 1 and II, Grove Dictionaries, Inc., New York, 2000.

Vasari, Giorgio, trans. George Bull, Lives of the Artists, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1965.

Wöfflin, Heinrich, Classic Art: An Introduction to the Italian Renaissance, Phaidon Press Limited, London, 1994 (first published 1952).

©John P. Walsh. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, which includes but is not limited to facsimile transmission, photocopying, recording, rekeying, or using any information storage or retrieval system.

FOOTNOTES: Available at link below.