FEATURE Image: “White House” by Diego Cambiaso is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

“The advent of the new president changed everything. The Roosevelts transformed the White House as completely as the swift march of public thoughts and events had changed the country. No longer did the Executive Mansion resemble a medieval castle besieged by the forces of progress. The drawbridges were figuratively let down, and the moats drained of their timeworn prejudices. The archers of reaction withdrew from their turrets, and the victorious New Deal army took over the battlements.” George Abell and Evelyn Gordon, Let Them Eat Caviar, Dodge Publishing Co., New York, 1937.

“Even that son of a bitch looks impressive in that getup!” Alice Roosevelt Longworth (1884-1980), at the White House after visiting President Warren Harding in the Oval Office. Quoted in Katherine Graham’s Washington, Knopf, 2002.

Alice Roosevelt was President Teddy Roosevelt’s oldest child and the only child of Roosevelt and his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, who died in childbirth. Alice grew up to be an independent, unconventional and outspoken “first daughter” and was an important figure in the women’s movement in the first half of the 20th century.

Alice Longworth was perfectly realistic about Harding—and didn’t like the Republican president very much. Sen. Brandegee of Connecticut, a member of Harding’s own inner circle, called the former newspaper owner of The Marion Star, Senator from Ohio, and 29th U.S. President, “no world-beater, but he’s the best of the second-raters.”

“[The Wilsons] finally settled on a house in the 2300 block of S Street, Northwest, and purchased it…[W]e rode by everyday, and the President was eager as a bridegroom about getting back to private life. He seemed to gain new strength as he shed the idea of responsibility and assumed the freedom of a civilian. But he did not forget his dreams.” Colonel Edmund W. Starling, Starling of the White House…as told to Thomas Sugrue…, Simon & Schuster.

Colonel Edmund William Starling (1875-1944) was chief of the Secret Service detail in the White House from 1914 to 1943. In his thirty years of service at the White House he was responsible for the personal safety of five President of the United States—Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Starling idolized Woodrow Wilson. His first exposure to Wilson left him “in a daze.” Born in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, the posthumous book is based on over 11,000 personal letters Starling wrote over the decades, mostly to his mother back home. Starling’s ashes are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

SOURCES: http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/ewstarling.htm; https://hoptownchronicle.org/hopkinsville-native-edmund-w-starling-protected-five-presidents-as-a-secret-service-agent/

“As Senate majority leader, I participated in many private conferences with President Franklin D. Roosevelt….Usually we would talk in his bedroom at the White House, and the President, wrapped in his cherished gray bathrobe, which he clung to year after year….would interrupt work on a pile of papers and puff at a cigarette through his long ivory holder as we exchanged views.” Alben W. Barkley (1877-1956), That Reminds Me, 1954.

Senator Barkley (later Vice President Barkley under President Harry S. Truman) describes an almost iconic FDR- one can almost imagine a bespectacled 32nd president smoking a cigarette from a long cigarette (in this instance, ivory) holder and jauntily thrusting his chin forward.

Alben W. Barkley, Democrat of Kentucky, was one of the most prominent American politicians of the first half of the 20th Century. Barkley hoped expectantly to someday be the U.S. President–or at least his party’s sometime presidential nominee, particularly in 1952. The longtime majority leader of the U.S. Senate had to settle, however, for being a one-term vice-president in the executive branch. After Truman chose Barkley to be his running mate in 1948 and that ticket triumphed in one of American history’s most astounding upsets, Alben Barkley became a popular national figure known everywhere as “The Veep.” Like his Kentucky forebear Abraham Lincoln, Vice President Barkley was a noted story-teller and often started his sentence with, “And that reminds me…”

“It was all gone now-the life-affirming, life-enhancing zest, the brilliance, the wit, the cool commitment, the steady purpose….[President Kennedy] had so little time: it was as if Jackson had died before the nullification controversy and the Bank War, as if Lincoln had been killed six months after Gettysburg or Franklin Roosevelt at the end of 1935 or Truman before the Marshall Plan.” Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. (1917-2007) on the death of JFK. From A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. was an American historian who resigned from Harvard and was appointed Special Assistant to the President in the Kennedy Administration in January 1961. Per Kennedy’s desire, Schlesinger served as a sort of ad hoc roving reporter and troubleshooter on behalf of the president. In February 1961, Schlesinger was told of the plans for what developed into the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 and wrote a memorandum to the president telling him that he opposed the action. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 Schlesinger aided United Nations ambassador Adlai Stevenson on his presentation to the world body on behalf of the Kennedy Administration’s ultimately successful efforts to peacefully remove Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. On November 22, 1963, Schlesinger had flown to New York for a luncheon with Washington Post owner Katharine Graham and the editors of her magazine, Newsweek. As they still sipped pre-luncheon libations and amiably talked about upcoming college football games that weekend, a young man in shirtsleeves suddenly entered the gathering. He tentatively announced to the group that, as Schlesinger relates in A Thousand Days, “the President has been shot in the head in Texas.”

“[George Washington’s] mind was great and powerful, without being of the very first order; his penetration strong, though not so acute as that of a Newton, Bacon, or Locke; and as far as he saw, no judgment was ever sounder. It was slow in operation, being little aided by invention or imagination, but sure in conclusion.” Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), U.S. president, Letter, January 1814.

After returning from France where he served as Minister Plenipotentiary with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin in Paris in the mid-to-late 1780’s, Thomas Jefferson accepted President George Washington’s invitation to serve as the nation’s first Secretary of State in the early 1790’s. Jefferson eventually left Washington’s cabinet over his opposition to Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s promotion of a national debt and national bank in contrast to Jefferson’s vision of a minimalist federal government (see Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, Random House, 1998, pp. 221-222). Thomas Jefferson was elected the third president of the United States in 1800 and served two terms as president. In 1803 Jefferson transacted the Louisiana Purchase that doubled the size of the United States and in the process acquired the most fertile tract of land of its size on Earth.

“During the inaugural parade [President George H.W.] Bush kept darting in and out of his limousine…These pop-outs were much better received than the Jimmy Carter business of walking the whole parade route. We Americans like our populists in small doses and preferably from an elitist.” P.J. O’Rourke, PARLIAMENT OF WHORES, Atlantic Monthly Press, 1991.

The Bushes were a big family and family oriented. O’Rourke reported in his best-selling book that on the first night of Bush’s presidency 28 members of the Bush family spent it at the White House.

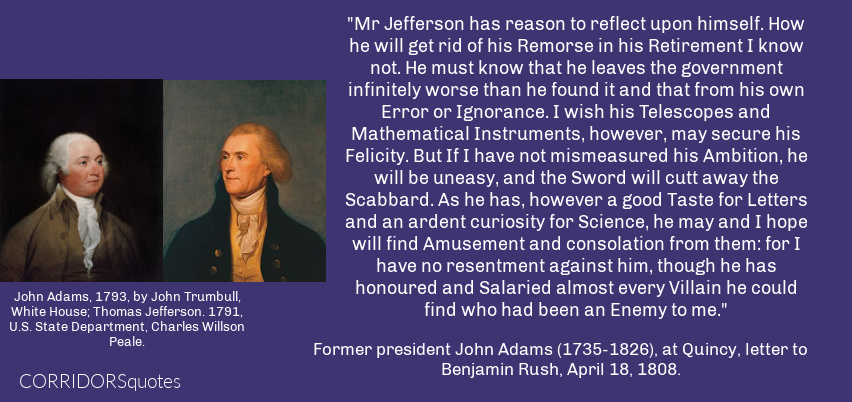

“Mr Jefferson has reason to reflect upon himself. How he will get rid of his Remorse in his Retirement I know not. He must know that he leaves the government infinitely worse than he found it and that from his own Error or Ignorance. I wish his Telescopes and Mathematical Instruments, however, may secure his Felicity. But If I have not mismeasured his Ambition, he will be uneasy, and the Sword will cutt away the Scabbard. As he has, however a good Taste for Letters and an ardent curiosity for Science, he may and I hope will find Amusement and consolation from them: for I have no resentment against him, though he has honoured and Salaried almost every Villain he could find who had been an Enemy to me.” Former president John Adams (1735-1826), at Quincy, letter to Benjamin Rush, April 18, 1808.

The punctuation and capitalization are Adams’ original. see– https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5238

John Adams (1735-1826), the second president of the United States, a Federalist, and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), a Democratic-Republican, were fierce political rivals. Both lawyers—Adams from Massachusetts and Jefferson from Virginia—each were enlightened political liberals who served in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia as well as headed the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. Adams and jefferson also served together as ministers to France in the 1780’s. Into the 1790’s, as president (Adams) and vying to be (Jefferson), each served opposing visions for the direction of the new nation. At their extreme, the Federalists advocated to establish a strong Federal government that could alienate the individual rights of large groups. Jefferson’s vision of limited government included his advocacy in certain instances for state government to have the right to resist those federal laws that were injurious to local interest.

Jefferson’s narrow victory in the presidential election of 1800 made John Adams the nation’s first one-term president, and sent the New England patriarch into early retirement to Quincy, Massachusetts. For the next decade, John Adams harbored a barely hidden resentment of his political rival, if not enemy when measured by some of their florid rhetoric. Though these two sparring giants of the early republic eventually resumed civil correspondence—Adams and Jefferson stayed in contact until the day they died, both remarkably on the same day, July 4, 1826— Adams had been especially upset by the relentless propaganda campaign of Jefferson’s Republican party against him during the second president’s first term. The years-long libelous accusations described President Adams, in part, as narcissistic, incompetent, dangerous to democracy, unbalanced, and corrupt—all of which Jefferson had personally paid for and approved and which led to a premature and hasty departure of Adams as chief executive on March 4, 1801. (See Joseph J. Ellis, American Sphnix: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, Random House, 1998, pp. 281-82).

Also see- https://openendedsocialstudies.org/2018/09/25/adams-jefferson-and-two-visions-for-the-united-states/

“Isn’t it nice that Calvin is President? You know we never really had room before for a dog.” Grace Coolidge (1879-1957), First Lady of the U.S. (1923-1929), in 1927.

Grace Coolidge was the wife of the 30th President of the U.S., Calvin Coolidge. Throughout her husband’s career, whether as Governor of Massachusetts, Vice-President, or President, Grace Coolidge avoided politics. Though the young Grace broke off a marriage engagement to marry Coolidge, her mother advised against marrying this young man. Calvin Coolidge and Grace Coolidge married on October 4, 1905—and Calvin Coolidge never settled his differences with his mother-in-law who felt her daughter was completely responsible for his rising political fortunes. The Coolidges had two sons, John (1906–2000) and Calvin (1908–1924). After Calvin Coolidge, Jr. died of blood poisoning in July 1924, the Coolidges were inconsolable. The story is well-known: while playing lawn tennis with his brother, John, at the White House, the teenager developed a blister on one of his toes. Within the week, the 16-year-old was dead of a blood infection despite being admitted to Walter Reed Army Medical Center. (see- https://www.coolidgefoundation.org/blog/the-medical-context-of-calvin-jr-s-untimely-death/)

By 1921, the wife of Vice-President Coolidge entered Washington society and quickly became the most popular woman in the capital. In 1927 when Mrs. Coolidge made these remarks, the world that her husband was facing was in flux. In 1927, as France called to outlaw war, which was endorsed by the U.S, a Great Depression already began in Germany with its economic collapse on “Black Friday.” After President Coolidge called for a Naval Disarmament Conference, only a couple of global powers showed up.

The world seemed to be getting smaller in 1927. In May 1927 American Charles Lindbergh flew solo, nonstop, from New York to Paris and started the era of transatlantic air travel. Regular transatlantic telephone service also began in 1927. In the U.S., as the stock market boomed, much of it on shaky credit, lawyers and doctors earned around 3½ times more than a teacher or factory worker. Baltimore-born “Babe” Ruth hit a record 60 home runs in New York.

The first full-length sound motion picture, The Jazz Singer, opened in 1927. In Chicago there was an important art exhibition of Chinese Buddhist art of the Wei Dynasty. In 1927, Hemingway published Men without Women; Willa Cather published Death Comes for the Archbishop; and Thomas Mann published The Magic Mountain. That year’s Pulitzer Prize went to Thornton Wilder’s second novel, The Bridge of the San Luis Rey. It told the story of people who unexpectedly die together in a rope bridge collapse in Peru and the friar who witnessed the accident looking to figure out the possibly cosmic answers as to why.

“The days of transition from Kennedy to Johnson were as hard on me as they were on anyone else–harder. I was losing a dog and gaining a President I didn’t know. Not only didn’t I know him, I didn’t think I wanted to know him. He wasn’t boyish or good-natured or quick-witted like Kennedy and I heard him cussing out the help when things weren’t done fast enough.” Traphes Bryant, Dog Days at the White House, 1975.

In 1951, Traphes Bryant started out at the White House working as an electrician in the afternoons. Bryant moved on to respond to general maintenance calls including a broken White House elevator. In the 1950’s Bryant was already looking after the First Family’s pets, both for the Trumans and, later, the Eisenhowers. The line of work became official for Traphes Bryant in 1961 when John Kennedy became president.

Kennedy asked Bryant to become the new presidential kennel keeper. The president liked how Bryant trained the dogs to meet the presidential helicopter that would often be seen in photographs and films.

Though Kennedy himself was allergic to some animals, First Lady Jackie Kennedy adored all sorts of animals. During the next 1000 days while in office, the Kennedys kept several pets. At one point the first family, which included children Caroline and John, Jr., had nine dogs. The Kennedys also kept hamsters, horses, birds, a rabbit, and a cat. Some of the animals were gifts from foreign heads of state.

In 1961 Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev sent the Kennedys a mixed breed dog named Pushinka. The dog’s mother had been sent into orbit in 1960 on Korabl-Sputnik 2. While a surprise, the Kennedy’s welcomed the Russian’s canine gift. In fact, Kennedy’s Welsh terrier, Charlie, not only had a new companion but a new mate: Pushinka gave birth to four puppies fathered by Charlie. Kennedy called the litter, “the pupniks.”

Bryant was officially in charge of Pushinka’s and Charlie’s grooming, exercise, and diet—and all the rest though those responsibilities ended abruptly for Kennedy in November 1963.

see BRYANT, TRAPHES L.: ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW – JFK #1, 5/13/1964; Traphes Bryant, Dog Days at the White House, 1975; Katherine Graham’s Washington, Knopf, 2002, pp. 542-43; https://www.facebook.com/WhiteHouseHistory/posts/traphes-bryant-pictured-here-had-been-a-white-house-electrician-since-1948-worki/3374666809225225/

“Nancy Dickerson wrote that ‘The LBJ social style was something of a shock to the capital. Starting right at the White House, the Johnson way was different…It’s difficult to comprehend the LBJ style because even by Texas standards he had large impulses. When the Johnsons said, ‘You all come,’ they meant it. Their lack of inhibition was new in Washington, a Southern city in the East. LBJ was a cowboy, and though that mythic figure is in the best American tradition, the Washington establishment, the press and the country were unaccustomed to a cowboy in the White House. The city shook its collective head.’ …However, the Johnsons gradually began to put their own mark on the city.” Katharine Graham, Katharine Graham’s Washington, Knopf, 2002, p. 458.

I always thought [President Jimmy] Carter was great…That kind of brain power made him the smartest president we’ve had in my time. His failing was as a politician. He did not know how to organize the White House and how to get along with Congress. Carter promised he was not going to work with the bureaucracy in Washington. He would be the people’s president.. He did it — and it doesn’t work. [Carter] proved that. Conversations with Cronkite: Walter Cronkite and Don Carleton, University of Texas at Austin, 2010, p.320.

“In a way the criticism of Washington is extremely healthy. Because the idea of Thomas Jefferson was that to make the system work, Americans always had to be in a state of semi-revolution against the government. He would have been terrified to think that in 2001 Americans might be uncritical of Washington and let it steal their liberties.” Michael Beschloss, U.S. historian, quoted in “Why Do They Hate Washington?” by Sally Quinn, The Washington Post, April 12, 2001.

“Just the day before, I’d joked about being the vice president when I addressed a group of newspapermen covering the Senate. One of them called me Mr. Vice President and I said, “Smile when you say that,” and I told them that the Senate was the greatest place in the world and that I wish I was still a senator. “I was getting along fine,” I said, “until I stuck out my neck too far and got too famous. And then they made me VP and now I can’t do anything.” But now I wasn’t the vice president any longer, and there was plenty to do.” Harry S. Truman, 33rd U.S. President, Where the Buck Stops: The Personal and Private Writings of Harry S. Truman, ed. Margaret Truman, 1989.

“Do you know who the patient is in the emergency room?” “Yes.” “Would you give me his name, please?” I said, “It’s Reagan. R-E-A-G-A-N.” I waited for a reaction. “First name?” “Ron.” “Address?” I said, “1600 Pennsylvania.” His pencil stopped in mid-scratch. He finally looked up. “You mean…?” I said, “Yes. You have the president of the United States in there.” Michael K. Deaver at George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C. after the assassination attempt on President Reagan on March 30, 1981. From his Behind the Scenes, 1987.

On Monday afternoon, March 30, 1981, after giving a speech at the Washington Hilton Hotel at 1919 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., in Washington, D.C., President Reagan was shot by 25-year-old would-be assassin, John Hinckley, Jr. The president was slammed to the floor of the presidential limousine by a Secret Service agent during the first split seconds of the shooting in a bid to save his life. Later Reagan expressed his anger for being treated very roughly by the agent though the agent knew he was just doing his job. Under a pile of agents, the 70-year-old president was raced in the limousine to George Washington University Hospital about a mile away.

At first it was believed that the president was unhurt, but within minutes, still on the way to the emergency room, Reagan coughed up blood from his lungs.

At the hospital, the president walked on his own power about 15 yards into the emergency room. Once inside the hospital, Reagan slumped and was helped by Secret Service agents into a private room off the lobby.

As the hospital’s trauma team assembled, it was still not clear whether Reagan had been hit or not in the hail of 6 bullets shot in quick succession by the would-be assassin’s .22 caliber gun. Bullets struck James Brady, Reagan’s Press Secretary, in the head above his left eye; Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy in the chest; and D.C. police officer Thomas Delahanty in the back of his neck ricocheting off his spine. All of them would receive medical attention and survive.

The doctors were just starting their examination of the president when a green smocked-hospital orderly with a clipboard approached Michael K. Deaver, White House Deputy Chief of Staff and Reagan confidante, looking for information on the new patient. It soon became clear that Reagan had, indeed, been hit in the assassination attempt. A fragment of a bullet had ricocheted off the limousine’s armored car door and entered the new president below the armpit, traveled down his left side, bounced off a rib, punctured his lung, and stopped just inches from his heart.

“What convinces is conviction. You simply have to believe in the argument you are advancing. If you don’t you are as good as dead. The other person will sense something isn’t there, and no chain of reasoning, no matter how logical or elegant or brilliant, will win your case for you.” Lyndon B. Johnson, quoted in Doris Kearns Goodwin, Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream, St. Martin’s Press, 1991, p. 130.