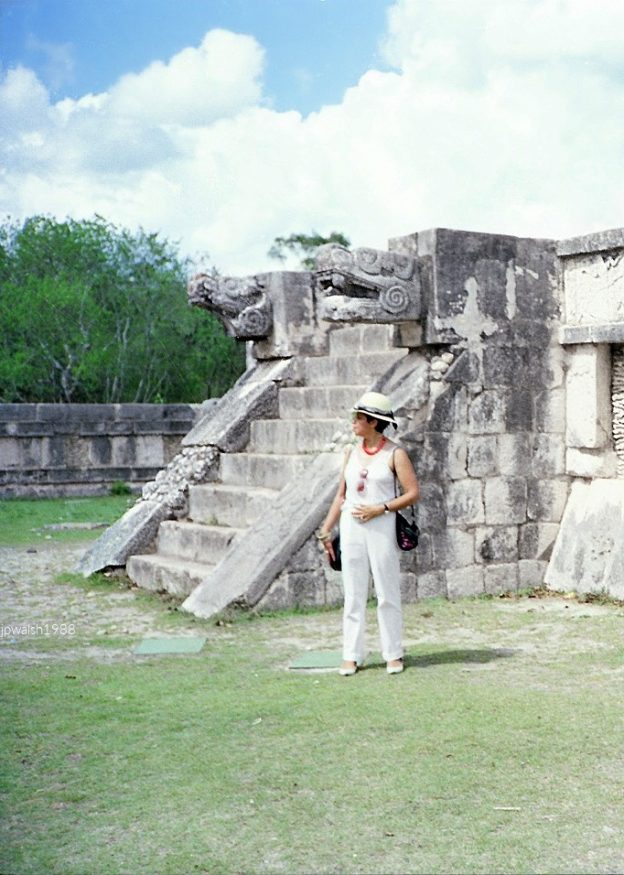

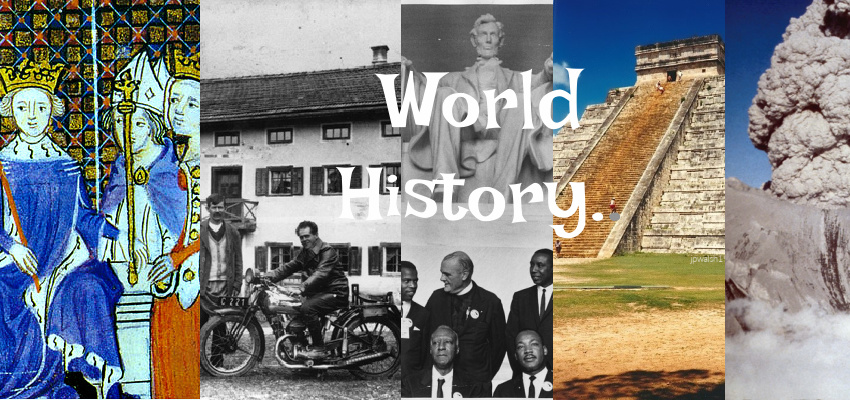

FEATURE image: Chichén-Itzá serpent head sculptures guard a staircase. Author’s photograph.

By John P. Walsh

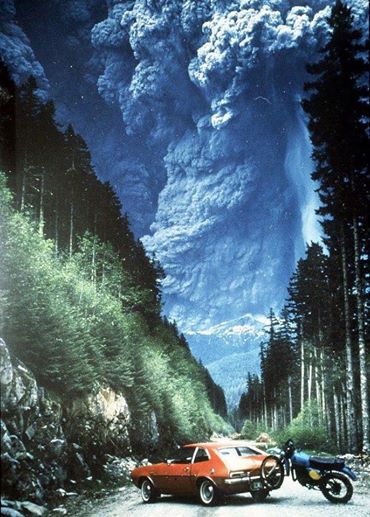

Cancún’s sandy spit of land at the northern tip of the Yucatán peninsula was uninhabited by the ancient Mayans. It was trodden by the conquistadores and used by pirates as a hide-out. Today, oozing like wet plaster into the Caribbean sea, the beaches are a new jet-age resort. I visited the Yucatán from Chicago for a few days in May 1988.

Though the tourist board in Cancún was telling of more resort development by the mid-1990s, it already boasted of 85 hotels and about 9,000 guest rooms during my trip.

After two days acclimating myself nicely to the Caribbean climate and working my way un poco with the Spanish language, I signed up with a local tour operator for a 12-hour bus tour. The destination was to one of the most famous sites on the Yucatán peninsula and the world: the ancient Mayan archeological site of Chichén-Itzá.

With its mysterious, virtually-intact looming pyramids and temples as well as startling tales of human sacrifice and one of the world’s most accurate cosmic calendar systems—all over 1,000 years old—I was excited to adventure out of the comfort of Cancún’s “Zona Hotelera” into the Yucatán jungle interior.

Setting out from Cancún into the Yucatán jungle

The ancient Mayan cities and later Spanish colonial ones that sit on top of them are a stark contrast to the touristy jet-set beaches of Cancún.

An extensive jungle stretches across the Yucatán’s three states of Quintana Roo, Campeche, and Yucatán that are inhabited by human communities as well as wild animals such as jaguars. We frequently saw black-headed, blue-bodied birds called Yucatán jays. We saw iguanas on sun-washed rocks.

I left the hotel and met the bus in Cancún town at 8:00 a.m. Francisco drove the air-conditioned 40-seater as Raúl toted a microphone and told the group about some of the things we were seeing along the way.

They took us out of Quintana Roo’s Cancún to Yucatán’s Chichén-Itzá about 125 miles away. On arrow-straight highway 180 we drove into small local communities along the two-lane road. We would reach Chichén-Itzá out of Valladolid, the Mayan/Spanish colonial city which is sometimes called the most colorful town in Mexico.

Chichén-Itzá’s famous complex of Mayan ruins dates from the Classic period of 600 CE to 1200 CE. Important archeological sites in the Yucatán still await reclamation from the jungle today –such as smaller Cobá in Quintana Roo. Guided tours are recommended for an extensive and remarkably safe visit into these interesting backwater places.

Highway 180: Route From Cancún to Valladolid

The bus climbed onto south highway 180 and followed it through villages such as Cocoyol, Catzin, Chemax, Xalaú, and others. Along the route there were thatched-roof dwellings which held patterned hammocks inside. Outside, dogs slinked around and small farm animals sometimes shared the road. The entire Yucatán peninsula is sparsley populated with only a fraction (about 4%) of Mexico’s total population.

Francisco told us that the thatched-roof dwellings were durable. One such dwelling could last almost 20 years. The huts were made of sticks which we were told kept dwellers cool and comfortable year-round. Raúl said that the average year-round temperature on the peninsula was 93 degrees Fahrenheit. Starting in April, humidity levels rose and the temperature hovered over 100 degrees. Thatched hut dwellings were the predominant local housing we saw from highway 180.

With exceptions, the lifestyle of modern Mayans has not strayed from their ancestors’ of the last millennia. Traditional Mayan homes are oval-shaped huts made of sticks bound together to form walls. Palm fronds are laid upon the wood frame for a peaked roof. Inside there is a main room usually with a dirt floor. Hammocks create a sleeping area.

In Valladolid, a Spanish colonial town founded in 1543, there were larger stores. From the bus windows, we saw local women in the huipil, the traditional garment worn by indigenous women from central Mexico to Central America, doing their errands. They outnumbered men on the street who were mostly absent on this sunny and hot May morning in the middle of the week.

Raúl said the men worked in Cancún during the week for about eight dollars a day, This wage was significantly higher than the $5 a day usually earned on the peninsula. The workers, Raúl said, are “smart” because when they are working, they live at the hotels where they eat, shower, and live rent-free. When they return home to the villages, they bring all of their earnings with them to their families. In most of these outlying towns it requires about $40 per week in income to meet living expenses, whereas workers in Cancún can earn nearly twice that amount.

Iglesia de San Servacio in Valladolid was built in 1545

The Iglesia de San Servacio is in the center of Valladolid on the south side of the main square. It was founded and built by Fr. Francisco Hernandez on March 24, 1545.

In 1705 part of the original church was demolished by order of the Benedictine bishop of Yucatán, Pedro Reyes de los Ríos de Lamadrid (1657-1714). The bishop ordered this partial demolition following the desecration of the sacred building during a political battle in July 1703 known as the “Crime of Mayors.”

July 1703: San Servicio desecrated in the “Crime of Mayors”

After Captain Hipólito de Osorno lost political favor in Valladolid he decided, together with his lawyer Pedro Gabriel de Covarrubias, to take refuge in the church of San Servacio.

But the political excitement of the time had reached an uncontrollable situation. In the pre-dawn hours of July 1703, a frenzied mob, led by Valladolid’s newly-elected mayors, Señors Avuso and Tovar, broke into the sacred enclosure.

The lawyer De Covarrubias was killed in the church after being driven through by a spear. His blood spilled on the altar and stained it. The captain was mortally wounded when the mob found him hidden behind the organ. The ruckus in no way benefitted the two new mayors. Both Señors Ayuso and Tovar were found guilty of murder and hanged.

Due to this murder in the cathedral the bishop had it rebuilt in 1706 as it is seen today. The altar’s position was moved to face north and west towards Rome. The church building is located on Valladolid’s main square named after Francisco Cantón Rosado (1833-1917), a conservative governor of Yucatán (1898-1902).

In early 18th Century Yucatán, a Benedictine Bishop and Franciscan Church

The church building’s main façade has a coat of arms carved on stone with arabesques, a royal crown, and a Franciscan cord. There are images of an eagle and a palm that were frequently used in the decoration of Franciscan churches in the Yucatán. Two square-shaped towers rise on either side of the central façade.

Ancient Mayans are 1,000 years older than the oldest books of the Bible

The Mayan civilization is shrouded in the mists of history. Archeologists, anthropologists and historians have speculated that they originated in about in 2600 BCE in the middle of the Bronze Age (3300 BCE to 1300 BCE). The origins of the Mayans therefore predate the oldest books of the Bible by 1,000 years.

Mayan technical skill extended to complex calendar systems and hieroglyphic writing whose images are in evidence at Chichén-Itzá. Mayan artisans were skillful weavers and potters and artifacts have been found in vast quantities at the site. The ancient Mayans also cleared routes for trade. Their main source of fresh water was from cenotes (sink-holes) and they stored rainwater in reservoirs called chultun.

Mayan civilization was socially complex and technologically evolved

Mayan culture made remarkable advances in mathematics and astronomy. Mayans are known for their impressive urban planning, farming methods, and architectural achievements. All of these impressive achievements are to be seen at Chichén-Itzá in its pyramids, temples, ball courts, palaces, and astronomical observatories.

By 300 BCE Mayan society had evolved into a hierarchical social structure where kings and priests ruled. Stretching from Cancún through the Yucatán, Belize, and Guatemala to the coast of the Pacific Ocean, Mayan civilization was a highly structured society. It consisted of several independent states, each possessed of several classes—a ruling class, warrior class, and agricultural class. The society reached its apex in the Classic period from about 200 CE to 900 CE.

The stone monuments at Chichén-Itzá were built as a ceremonial center during the Classic period. As it continues to impress visitors today, it accomplished the same thing for ancient Mayans over 1,000 years ago.

Toltecs absorb Ancient Mayans in about 900 A.D.

The decline of ancient Mayan civilization started around 900 CE as they began to surrender their independence to the Toltecs who absorbed them. The Toltecs were another pre- Colonial Mesoamerican civilization located in central Mexico that reached its height between around 900 to almost 1200 CE. Though Chichén-Itzá as a ceremonial center would not die for another 250 years, the city became a vestige of itself whose remnants alone of a great civilization survived when conquered by the Spanish colonists in the 15th century.

Chichén-Itzá today

It was hot and humid when we arrived into Chichén-Itzá. Discovered by explorers as early as the 1830’s—and opened to the public in 1922—it was today an impressive and expansive series of ancient stone monuments on a grassy 1200-acre campus carved out of jungle. Do people live further into the jungle? Raúl said about one mile from the road there are small communities of two or three hundred people who live in farther from the main road.

The pyramids and temples of Chichén-Itzá are the Yucatán’s best known monuments. The Mayan city was absorbed by the Toltecs in 987 CE. According to legend, a man named Kukulcan—who is the same figure as Quetzalcoatl from the Toltec capital of Tula —arrived from the west “for the redemption of his people.” In Chichén-Itzá, Kukulcan built this magnificent city which combined the Puuc style of the Mayans and the motifs of the Toltecs, namely, the feathered serpent, warriors, eagles and jaguars.

Maya explorers include American Edward Thompson (1857-1935) and others

Starting in the midnineteenth century and again at the end of the century, there was a range of scientists and explorers associated with the discovery and excavation of the archeological site of Chichén-Itzá that is seen today.

As its great natural water well (or cenote) likely gave Chichén-Itzá its name, one major figure worth considering is the early American explorer Edward Thompson (1857-1935). For most of his adult life Edward Thompson lived and worked at Chichén-Itzá including famously dredging and diving into the sacred well in search of treasure and human remains for evidence of legends of human sacrifices.

A diplomat by profession and an amateur archeologist, Thompson had an indefatigable curiosity about the ancient Mayan ceremonial city and did important work here.

As a young scholar Thompson was inspired by the writings of American explorer and diplomat John Lloyd Stephens (1805-1852). Together with English artist Frederick Catherwood (1799-1845) they were pivotal figures in the rediscovery of Maya civilization in Central America.

Catherwood’s detailed drawings of the ruins of the Maya civilization explored by Stephens led to best-selling books published in the early 1840s such as Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán and Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. These were illustrated works that introduced Europe and the United States to the civilization of the ancient Maya.

Stephens and Catherwood in turn had been inspired by earlier pioneers of scientists and explorers. Two figures who influenced them were Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) and Juan Galindo (1802–1840).

Von Humboldt was a Prussian geographer, naturalist, and explorer whose work in botanical geography led to the development of the field of biogeography. Galindo was an Anglo-Irish military and administrative officer in the short-lived liberal Federal Republic of Central America (1823-1841) and who was actively engaged in Maya archeology.

In 1847 the Caste War of Yucatán broke out limiting access to the Yucatán’s unexcavated ruins. The Caste War restricted the borders of Yucatán and Quintana Roo to all but indigenous Maya for nearly 60 years, making travel to the area dangerous. When the United States appointed Edward Thompson archaeological consul to the Yucatán in 1895 he became one of the first to explore the land since the Caste War.

Edward Thompson arrived in the Yucatán at Mérida in 1895. He had purchased land in 1894 that included the unexcavated site of Chichén-Itzá. For the next 30 years Thompson dedicated his life to exploring the site.

Thompson dredges Sacred Well

In 1904 Thompson started to explore the bottom of the sacred well— the cenote sagrado. Thompson used divers (including himself) and dredges. Over six years he brought up a fortune in gold, copper and jade as well as a wealth of vases, obsidian glass knives and Maya incense called copal. Thompson did some of his explorations for major American museums such as The Field Museum in Chicago and the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, among others.

From his arrival, the sacred well attracted Thompson’s intense interest. In his 1932 book, People of the Serpent, Thompson stated he became intrigued with the murky waters of the great well as soon as he first saw it from the top of El Castillo.

Though most ancient Maya artifacts as well as its codice books with its written language were destroyed by the local Catholic Church authorities in the 16th century, Thompson read the colonial Spanish accounts of Mayan history.

To implement his plan to explore the cenote, Thompson returned to his hometown of Boston where he raised money, took diving lessons, and constructed a specialized diving mechanism. Thompson sent the dredging bucket, winch, tackles, steel cables, derrick and 30-foot boom to Chichén-Itzá.

The dredge buckets brought up ornaments and objects of daily life. Thompson’s and another diver’s plunges discovered more precious treasures, including human skeletons. These discoveries were controversial. The fact that this ancient site was being disturbed brought critics. Further, Thompson was neither a scientist nor academic but simply an enthusiastic amateur. He published his Maya civilization studies in Popular Science Magazine. But these critiques aside, Thompson’s field work virtually single-handedly put Chichén-Itzá on every world explorer’s own bucket list.

Thompson excavated graves at the Ossario (High Priest’s Temple), the mid-sized step-style pyramid within the Ossario Group complex of Mayan temples found just south of the Kukulkan pyramid series. Thompson’s discoveries offered an outcome not unlike the cenote. In the Ossario pyramid and its cave Thompson found more jade, pottery, human bones, and various other ancient Mayan artifacts.

How Chichén-Itzá’s pyramids were built

Close to Chichén-Itzá Thompson discovered pits with quarried veins of lime gravel that the Mayan’s used for mortar. Nearby he found stones of calcite (to hammer), flint (to pick) and smooth stones used to produce flat surfaces on walls. Ancient Mayan craftsmen had no metal tools, but these stone implements helped scientists to reconstruct how the monumental buildings could be constructed. Thompson also uncovered shards of nephrite (a type of jade) as well as the so-called Mayan “date” stone, known later as the Tablet of the Initial Series. This stone let iconographers decipher the dates of Chichén-Itzá’s Classic period.

In 1926 Thompson’s land was seized by authorities of Mexico’s new nationalist government and Thompson was charged with removing artifacts illegally. It was only in 1944, almost a decade after Thompson’s death, that the Mexican Supreme Court ruled in the North American explorer’s favor.

Major sites at Chichén-Itzá

It is frankly thrilling to see the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican step pyramid. At nearly 80 feet tall, the pyramid dominates the center of the archaeological site of Chichén-Itzá. It was built between 700 and 1100 A.D.

El Castillo served as a temple to the god Kukulkan. Each side of the pyramid has 91 steps for a total of 364 steps. With the platform at the top, it equals the 365 days of the year. There are 52 smooth stone panels on each side of the pyramid which coordinates with the ancient Mayan calendar’s 52-year cycle. The nine terraces on each side of the pyramid represent the 18-month solar calendar.

Twice during Spring Equinox (March 21) at sunrise and sunset, the sunlight is observed to move down stair by stair from the top stair of the northern stairway until it touches the famous serpent head stone carving at the base of the pyramid. In a marvel of nature, sunlight and shadow work to form a “serpent” that appears to descend into the earth. The cosmological phenomenon was an important fertility symbol for the Mayans whose society was agricultural. It signaled that the golden sun had entered the earth in the form of a serpent and that it was time to plant corn.

Teobert Maler (1842–1917) was a pioneer of ancient Maya research. Maler’s expeditions to over 150 ruins in the Yucatán began secretly in the 1870s.

Several ruins Maler described and photographed had been discovered by him, and his photographs of its architecture and inscriptions aided further research in ancient Maya civilization.

Many sites Maler photographed were not visited by scientists until decades later. As the ruins were often further damaged by climate events or human impact—Maler’s photographs remain some of the best record of Maya ruins.

Because of Maler’s work at Chichén-Itzá and elsewhere, the German explorer is regarded as one of the most important research photographers of the 19th century.

OTHER PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS:

YUCHATAN JAYS – Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Tony Hisgett – originally posted to Flickr as Yucatan Jays – immature

IGUANA – CC BY-SA 2.0 view terms.