FEATIRE Image: 1951 Chevy Deluxe 5/2024 5.45mb

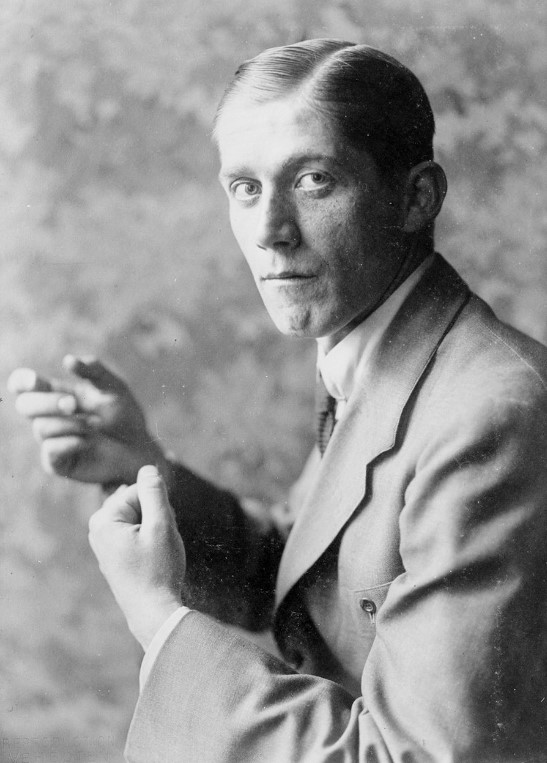

FEATURE Image: Fernand Harvey Lungren (1857-1932), The Café, 1882/84, oil on canvas. The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2014.

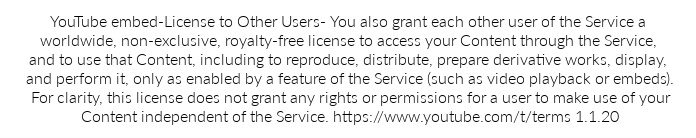

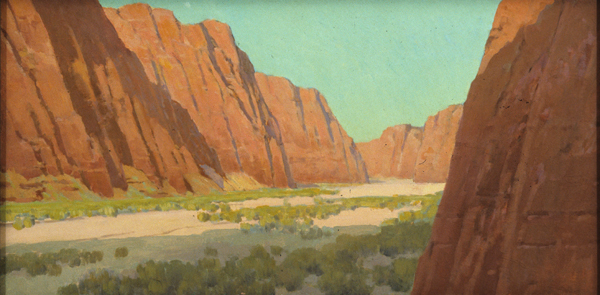

The artist, born in Sweden, moved with his family to Toledo, Ohio, as a child. Lungren wanted to be an artist but his father objected, wanting him to be a mining engineer. For a brief time, in 1874, Lungren attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor to study his father’s preferred subject. But after two years—Lungren’s father still opposed to his son being an artist— saw the younger Lungren rebel and prevail. In 1876 Lungren was able to study under Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) at the Pennsylvania Academy in Philadelphia and had Robert Frederick Blum (1857-1903), Alfred Laurens Brennan (1853-1921) and Joseph Pennell (1857-1926) as fellow students.

In winter 1877 the 20-year-old Lungren moved to New York City. With his first illustration published in 1879, he worked as an illustrator for Scribner’s Monthly (renamed Century in 1881) as well as for Nicholas (a children’s magazine) and as a contributor until 1903. He later worked for Harper’s Bazaar, McClure’s and The Outlook. Lungren’s illustrations included portraits, and social and street scenes.

In June 1882 Lungren sailed to Paris via Antwerp with a group of artists. In an 18-month stay in Paris he studied informally for two months at the Académie Julian, and viewed the latest French Impressionist artworks. He found his artistic purpose in Paris in direct observation and spent the balance of his time studying Parisian street scenes in the manner of the “new painting.”

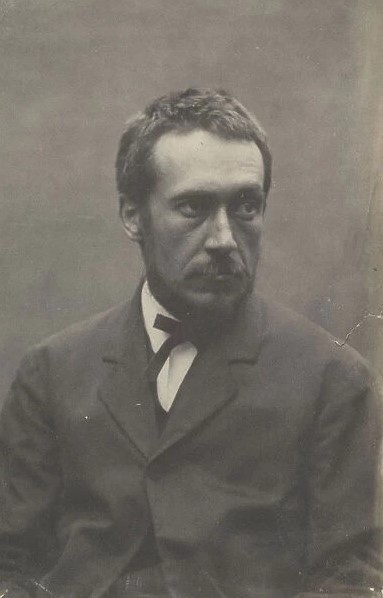

Lungren returned to New York City in 1883 and, soon afterwards, established a studio in Cincinnati, Ohio. Sponsored by the Santa Fe Railroad which wished to commission images of the Southwest to entice eastern tourists, Lungren made his first excursions west in the early 1890s. In 1892 he visited Santa Fe, New Mexico for the first time and, in the following years painted artworks inspired by his contact with American Indian culture and the desert landscape. This was the start of his lifelong association with American West and Southwest. In 1899 he showed these American desert works at the American Art Galleries in New York and afterwards at the Royal Academy in London and the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

When Lungren was in London he made pictures of street life and met several artists, including James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). In late 1900 Lungren traveled to Egypt with American pharmaceutical entrepreneur Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853-1936) and returned to New York via London in the next year. Lungren had married Henrietta Whipple in 1898 and they eventually moved to California in 1903, settling in Mission Canyon above Santa Barbara in 1906.

Lungren lived and work in California—including several notable trips to Death Valley starting in 1909 —until his death in 1932. After Lungren’s wife died in 1917, the artist helped found the Santa Barbara School of the Arts in 1920 and remained on its board until his death in 1932. He became a charter member of the Santa Barbara Art League and executed two works for dioramas at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Most of Lungren’s artwork, including hundreds of his paintings (some 300 works), were bestowed to Santa Barbara State Teachers College, which became the University of California, Santa Barbara, and are part of the University Art Museum

SOURCES:

J.A. Berger, Fernand Lungren: A Biography, Santa Barbara, 1936.

http://art-collections.museum.ucsb.edu/collections/show/44 – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://collection.sina.cn/zhuanlan/2022-03-11/detail-imcwipih7897380.d.html – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://www.artic.edu/articles/960/fernand-lungren-illuminated-in-the-cafe-and-the-city-of-lights – retrieved May 1, 2024.

FEATURE image: Oskar Kokoschka (Austrian, 1886-1980), Lady In Red, c. 1911, oil on canvas, 21 11/16 × 16 in. (55.09 × 40.64 cm), Milwaukee Art Museum. 9/2016. 6.05 mb 98% https://collection.mam.org/details.php?id=10718

When Oskar Kokoschka (Austrian, 1886-1980) painted Lady In Red that is in the Milwaukee Art Museum he was a starving artist living in Berlin. At 24 years old Kokoschka became associated with Berlin’s avant-garde and its writers, artists, and theatre actors. The artist knew some of the artists and others of Die Brücke and those associated with Der Sturm, the art and literary magazine. In June 1910 Paul Cassirer organized Kokoschka’s first major show. But Kokoschka’s involvement with the German Expressionists was limited as the young artist was dedicated to pursuing his own artistic ideas and forms. Commenting on this independence, Kokoschka wrote that he was “not going to submit…to anyone else’s control. That is freedom as I understand it.” (Oskar Kokoschka, My Life, translated from the German by David Britt, New York, Macmillan, 1974, p. 67). As Kokoschka developed the art of “seeing,” with his emphasis on depth perception, the local press saw young Kokoschka’s volatile unpredictability and called him “the wildest beast of all.”

Though Kokoschka studied art of the past masters to develop a unique individual style, he and Die Brücke did interact on ideas and formal problems which generated an artistic atmosphere in Berlin and Vienna. In 1912, Kokoschka started a disastrous affair with Alma Mahler (1879-1964), the widow of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). Its final ending in 1915 led to Kokoschka volunteering for the front lines in World War I and being seriously wounded in combat that year. The artist enlisted in the 15th Austrian Dragoon Regiment where, on the Ukrainian front, Kokoschka was seriously wounded by a bullet to the head and a bayonet wound to the chest. In 1916 Kokoschka was wounded by grenade fire on the Isonzo Front.

The Expressionists’ emotional involvement with world events affected each of their creative processes. In these experiences of personal and social upheaval, Kokoschka maintained that as an artist – and he viewed this role as an existential fact more than a choice – his life had less to do with often prefabricated ideologies, programs, and parties and, rather, with searching and crafting his unique outlook as a creative individual. “There is no such thing as a German, French, or Anglo-American Expressionism!” Kokoschka would argue, “There are only young people trying to find their bearings in the world.” (Kokoschka, My Life, p. 37).

Kokoschka’s individualism made him one of the supreme masters of Expressionism, an -ism he defied. His tempestuous canvases with harsh colors and disjointed angles produced compositions that were emotionally aggressive and meant to prod the viewer into discomfort and rage. As Kokoschka eschewed the main modernist movement of Expressionism for the discovery and practice of his own unique style, he became one of the few major artists (Max Beckmann is another) who will often not appear in the annals of mainstream 20th century modernism, though this exclusive outcome is likely what would satisfy “the wildest beast of all.”

SOURCES:

The Berlin Secession: Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany, Peter Paret, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980, p. 208.

Oskar Kokoschka, My Life, translated from the German by David Britt, New York, Macmillan, 1974.

https://oskar-kokoschka.ch/fr/1001/Biographie – retrieved May 1, 2024.

http://www.jottings.ca/carol/kokoschka.html#3 – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/kokoschka-oskar – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Marta_Wolff – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://upclose.christies.com/restitution/kunstsalon-cassirer – retrieved May 1, 2024.

https://www.gallery-weekend-berlin.de/journal/simon-elson-pate/ – retrieved May 1, 2024.

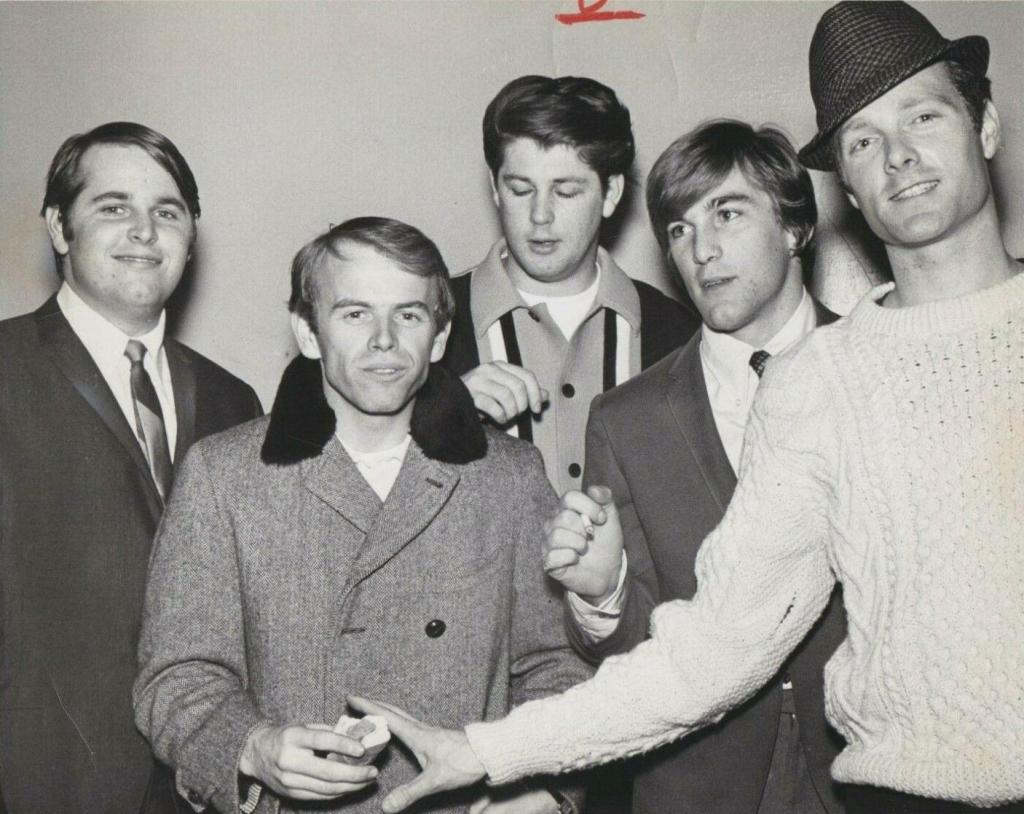

Feature Image: The Beach Boys in 1964; clockwise from left: Al Jardine, Mike Love, Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson. Trade ad for The Beach Boys’s single “California Girls”/”Let Him Run Wild.” Public Domain. Permission details The ad appeared in the 11 September 1965 issue of Billboard and can be dated from that publication; it is pre-1978. There are no copyright markings as can be seen at the full view link. The ad is not covered by any copyrights for Billboard. US Copyright Office page 3-magazines are collective works (PDF) “A notice for the collective work will not serve as the notice for advertisements inserted on behalf of persons other than the copyright owner of the collective work. These advertisements should each bear a separate notice in the name of the copyright owner of the advertisement.”

By John P. Walsh

On November 2, 1964 the Beach Boys invaded London, England for a television appearance and concert.

At the press conference 22-year-old Brian Wilson who in this period co-wrote, with 23-year-old Mike Love, “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” said he wanted to see the band someday record in England. Eventually in 1972 they did record in Holland. See – https://johnpwalshblog.com/2022/08/24/seafaring-treasure-in-classic-rock-the-backstories-of-blues-images-no-4-hit-ride-captain-ride-1970-and-the-beach-boys-twice-charting-sail-on-sailor-1973-1975/

With the press media in England Wilson admitted the Beach Boys had written and performed music on surfer subjects as well as cars but displayed anger as he denied that they had anything to do per se with “surfer music” and certainly not in originating or perpetrating it. Besides, Wilson offered that that phase was pretty much over. Their music was just their sound that people liked to listen to. In London and elsewhere he said that the Beach Boys had found new subjects particularly on social themes surrounding what it meant to be a young person in the mid1960’s.

Recorded and released as a single in August 1964, “When I Grow Up (To Be A Man)” was another song by Brian Wilson and Mike Love. Mike Love thought it may have had to do with Brian Wilson’s father’s concern for his sons’ masculinity in the glitzy music business (see Love, p. 92) as much as his criticism of Brian’s impending marriage in December 1964 to 16-year-old Marilyn Rovell, a member of the Honeys. Brian had asked for her hand in an expensive telephone call from Australia when the Beach Boys were on tour there and in New Zealand in January 1964 and more than once until the nuptials. Back in California, Wilson produced his song, “He’s a Doll,” for the Honeys who recorded it on February 17, 1964 and released it two months later, on April 13, 1964.

The Beach Boys’ first no. 1 single was one that was released in May 1964. They had been making music since 1962 and the last twelve months, since May 1963, had been busy and productive. Since spring of 1963 they had 3 top-5 hits (and two more top-10 hits). “Surfin’ U.S.A.” peaked at no. 3 in May 1963 and became Billboard’s no.1 song for the year. “Little Saint Nick” released in December 1963 peaked at no. 3 on the Billboard Christmas Singles chart. By the time “Fun, Fun, Fun” peaked at no. 5 in March 1964, everything had changed in rock ‘n roll music in America, and particularly for the Beach Boys. The change was marked by the appearance of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. Literally half the country – 74 million people – tuned in and the impact was immediate. When the Beach Boys heard the hordes of screaming fans for the Fab Four, Brian Wilson thought for a moment about quitting, disappointed that so much of what the California band had been working on and striving for had suddenly been eclipsed – and by Brits no less. Brian Wilson set to work to complete more original material and was more open to experimenting with arrangements and instrumentation to achieve a new sound. Though the Beach Boys were replaced in the top spot on Billboard’s year-end singles in 1964 by the Beatles (“I Want To Hold Your Hand”) and the Beatles locked up the second spot as well (“She Loves You”), “I Get Around,” was in the top 5 that year.

On July 13, 1964, the Beach Boy’s sixth album All Summer Long was released on Capitol records with “I Get Around” its first track. Considered the band’s first artistically unified collection of songs, All Summer Long reached the Billboard 200 two weeks later and rose rapidly to peak at no.4 on August 22, 1964. According to Mike Love, the lyrics developed out of their experiences describing the band’s restlessness with “instant fame, some fortune” and looking to find new spaces and places “where the kids are hip.” By the second and final verses the narrator has moved from monotonous boredom in search of something more to boasting that he has the fastest car and great success with the women. In those first few months of 1964 the Beach Boys had moved from wunderkind band to a personal and musical maturity. On “I Get Around” Dennis Wilson biographer Jon Stebbins wrote that it “is clearly ahead of its time, and it signals the speed at which Brian had developed. With its edgy guitar/sax bursts doubled with trebly reverbed Fender flicks, electric-organ fills, and an arrangement that stops, goes, accelerates, and then stops and goes a few more times, the song is nearly otherworldly in its inventiveness. Each band member’s voice is showcased, and this helps to make this single as good as any pop record ever made.” In February 1965, All Summer Long was certified gold by the RIAA. So that by the time of the Beach Boys’ American invasion of Britain in November 1964 they continued their counter to the British invasion of the Beatles in February 1964.

Though released after the onset of Beatlemania in March 1964, the material for the Beach Boys’ album, Shut Down Volume Two, was conceived, written, and produced in late 1963 and early 1964. The Beatles’ impetus on the Beach Boys to more subtly integrate older musical sources to something new and original would still be several weeks and months in the offing. The lead track, Fun, Fun, Fun was recorded in the first week of January 1964 and released as a single on February 3, 1964, less than a week before the Beatles’ first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. That appearance (and the Rolling Stones’ stateside arrival in June 1964) is considered the beginning of rock music’s British Invasion and a milestone in American pop culture. Meanwhile, the lovely melancholic The Warmth of the Sun on side one of Shut Down Volume Two was written by Brian Wilson and Mike Love on the night of the Kennedy assassination in November 1963. Considered one of the finer early Beach Boys tunes, the Wilson-Love song collaboration would be kicked up more than a notch in 1964. Seemingly overnight, in front of the whole world, in that musical moment of February-March 1964, the Beatles marked the beginning of the 1960’s as we know it, and the Beach Boys, freely admitting to the passing of their car and surfer craze and, with The Warmth of the Sun, if written for JFK, Camelot, marked the era’s ending. Both were appropriate junctures for young developing bands: the Beatles, in 1964, out front of the Beach Boys to start. Although The Warmth of the Sun was on the best-selling Shut Down Vol. II (no. 13 on the Billboard 200), it didn’t get too much air play until it was placed on the B-side of the single Dance, Dance, Dance at the end of the year. This followed the release of the Beach Boys’ All Summer Long (I Get Around; Wendy) in July 1964 and anticipated The Beach Boys Today! (When I Grow Up (To Be a Man); Help Me, Rhonda) in March 1965. Both studio LPs – the Beach Boys’ sixth and eighth – grabbed back some of the rock pop critical and popular initiative they had prior to the Beatles. As the mid1960s were now in full swing, it also started the informal competition between two 20-something composers – namely, Southern Californian Brian Wilson and Liverpudlian Paul McCartney.

Wilson’s “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)” is one of the first rock songs to present a teenager thinking in the first person about serious matters on his future adulthood. It is one of the first top-40 songs (no.1 in Canada and no. 9 in the U.S.) to use the idiomatic term “turn on” (as in “Will I dig the same things that turned me on as a kid?”). It is also an intelligent question, in Mike Love’s part, of what sort of woman he will pursue in the near future as a man.

In Brian Wilson’s part, the composition’s 14-year-old narrator asks another pertinent question in the song: “Will I love my wife for the rest of my life?” As Wilson was soon getting married in real life, there is an invested urgency and emotional depth in the teenager’s question. At the same time, it is a careful, perhaps even emotionally prescient question as it does not query their marital status (Wilson and Marilyn Rovell were divorced in 1979). The lyrics are creatively astute in that “When I Grow Up” conveys these late adolescence complexities in an uplifting tone of apparent innocence, sincere interest, and hopeful enthusiasm by its serious teenage narrator.

The manager of the Beach Boys was the Wilson brothers’ father, Murry. Murry Wilson mused out loud whether his eldest son, Brian Wilson, at 22 years old, was possibly immature in his choices. Yet Brian, despite his mental breakdowns, was taking charge in his personal and professional life.

Before the March 1965 album, The Beach Boys Today!, was completed and whose recording began in August 1964 with “When I Grow Up (To Be A Man),” Murry was fired by Brian and didn’t return. Despite Murry’s expressed doubts and his eldest son’s impending marriage, Brian Wilson’s music was growing and developing by leaps and bounds. Surrounded by the smell of cannabis that Brian started smoking regularly, new musical insight is heard in When I Grow Up (To Be A Man). It is one of the first Beach Boys’ songs featuring those oddly changing, yet harmonious chords that do not stay in one key for more than a few measures. That musical structure characterized many of Brian Wilson’s finest compositions going forward. The young producer also again deployed a harpsichord – it can be heard in I Get Around – which was a creative use of a 16th century Baroque instrument which was unusual for a mid-1960’s pop rock song. The Beach Boys’ example, however, led to its use and that of other classical music instruments much more by rock bands afterwards. The track also features, as Jon Stebbins maintains, “one of Dennis’s best studio drum performances” (see – The Beach Boys FAQS, 2011, p. 53).

The Beach Boys Today! started recording in August 1964 and was completed in January 1965. It was recorded at three different studios in Hollywood (United Western Recorders, Gold Star Studios, and RCA Studios) using over 30 session musicians and was released on March 8, 1965. In those months Brian also suffered breakdowns that he later explained as owing to circumstances. “I used to be Mr. Everything, “he said, “I was run down mentally and emotionally because I was running around, jumping on jets from one city to another on one-night stands, also producing, writing, arranging, singing, planning, teaching – to the point where I had no peace of mind and no chance to actually sit down and think or even rest” (quoted in Badman, p. 74). Love saw it differently attributing some of it to the impending psychedelic drug culture that characterized the mid to late 1960s and Brian’s novel, if limited, involvement (see Love, p. 185). A dismissed Murry stayed in Hawthorne, California at home (3701 W. 119th Street; torn down in the mid1980s) where youngest brother, Carl Wilson, was still living and where he listened many times to Introducing… The Beatles and Meet the Beatles! in his room.

In June 1964 they recorded The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album (released in November 1964) and since July had been in Hawaii and Arizona to begin their 33-day, 42-concert Surfin’ Safari tour. After Murry was fired the Beach Boys became more involved in their concert date strategy, such as playing nearby secondary and tertiary cities as well as playing in big ones (see Love, p. 98). In early August 1964, “When I Grow Up (To Be A Man)” was the first song recorded for The Beach Boys Today! and released as a single on August 24, 1964. It is a philosophical song whose music is an artistic progression for Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys with its rich and profound instrumental arrangement and 4-part vocal harmonies that are fluid and ethereal (See – https://www.songfacts.com/lyrics/the-beach-boys/the-warmth-of-the-sun – retrieved April 16, 2024). Wilson’s use of the harpsichord in the song could stem from “easy listening” sources such as Henry Mancini’s Playboy’s Theme (1960) from the late-night TV show or other of his film scores. Rock critic Richard Meltzer later observed that it was When I Grow Up (To be a Man) that marked the moment when the Beach Boys “abruptly ceased to be boys” (quoted in O’Regan, Jody (2014). When I Grow Up: The Development of the Beach Boys’ Sound (1962-1966) (PDF) (Thesis). Queensland Conservatorium, p. 253). In his 2016 memoir, Love wrote that the song was “probably influenced” by Murry Wilson who constantly challenged Brian’s manhood.

When the Beach Boys landed in London in early November 1964 there was an electricity in the air surrounding them. Since February they had a top-5 hit (Fun, Fun, Fun), no. 1 song (“I Get Around”), a no.1 album (Beach Boys Concert), TV and movie appearances, live concert tours and so on. They had two follow-up top-10 singles – When I Grow Up (To Be Man) and Dance, Dance, Dance. The band’s leader, Brian Wilson, was getting married in December. There was a competition between the Beach Boys and the Beatles who, so far, dominated the field, despite the Beach Boys’ tremendous accomplishment. Their arrival into Britain was greeted with screaming fans and lots of media attention. As Mike Love put it, “Five singles and four albums – by any measure, an extraordinary year. It did nothing to slow down the Beatles, who had nine Top 10 singles and six albums that charted either 1 or 2, but both commercially and artistically, we were doing our best to hold our own.” (Love, p. 97)

They flew back home and did more concerts until, on December 7, 1964, Brian Wilson and Marilyn Rovell married. As Mike Love observed, it was Brian Wilson who was under the most “pressure” of “trying to keep pace with the Beatles, trying to satisfy the [record] label, trying to become a global band.” (Love, p. 104). On December 23, 1964, Brian Wilson was on an airplane from L.A. to Houston, Texas, to start a 25-date concert tour when he announced he had had enough of the hectic lifestyle of a pop rocker. Getting back to L.A., he returned to the vacant family homestead in Hawthorne and had a long talk with his mother who, Brian said, “sort of straightened me out” (quoted in The Beach Boys’ America’s Band, Johnny Morgan, p.81). Despite Brian’s marriage and breakdown, the Beach Boys road show carried on. Glen Campbell filled in for Brian to finish out the concert dates in Texas that ended the year 1964 for the Beach Boys. It was to be a busy January 1965.

SOURCES:

The Beach Boys: America’s Band, Johnny Morgan, Union Square & Co.; Illustrated edition, 2015, pp. 63-81.

The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America’s Greatest Band on Stage and in the Studio, Keith Badman, Backbeat Books; First Edition, 2004.

Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy, Penguin Publishing Group, Mike Love, 2016, p. 97; pp. 159-160.

Dennis Wilson: The Real Beach Boy, Jon Stebbins, ECW Press, 2000 p.39.

The Beach Boys FAQ, All That’s Left to Know about America’s Band, Jon Stebbins, Backbeat Books, 2011.

When I Grow Up: The Development of the Beach Boys’ Sound (1962-1966) (Thesis), Jody O’Regan (2014). Queensland Conservatorium.

A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes: My Story, Annette Funicello, Patricia Romanowski (1994). Hyperion. p. 13.

Santoli, Lorraine (Spring 1993). “Annette – As Ears Go By”. Disney News Magazine. p. 18.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beach_Boys – retrieved April 10, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beach_Boys_Today! – retrieved April 10, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/When_I_Grow_Up_(To_Be_a_Man) – retrieved April 10, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billboard_Year-End_Hot_100_singles_of_1963 – retrieved April 12, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles_in_1963– retrieved April 12, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billboard_Year-End_Hot_100_singles_of_1964-– retrieved April 10, 2024.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_top-ten_singles_in_1964 – retrieved April 12, 2024

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Billboard_Hot_100_number_ones_of_1964 – retrieved April 12, 2024.

Feature Image: Construction worker, April 2020 3.21mb.

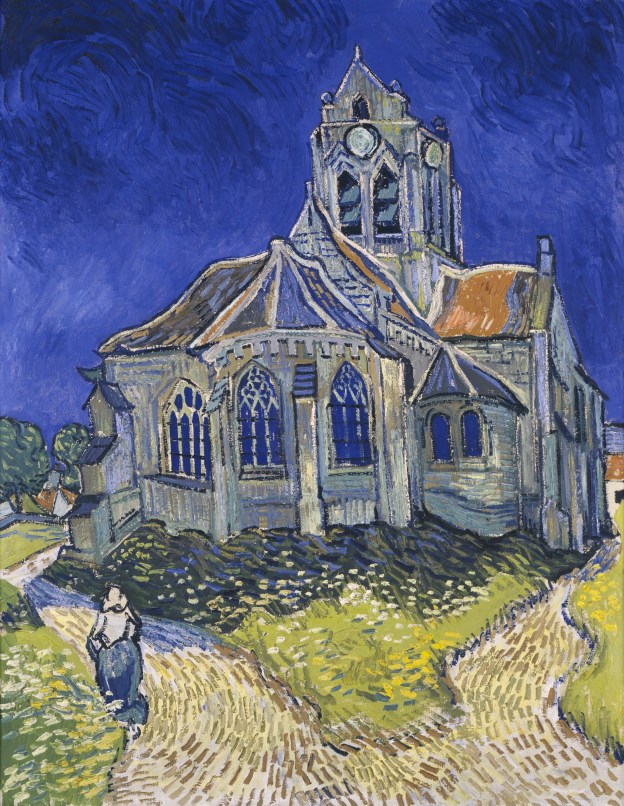

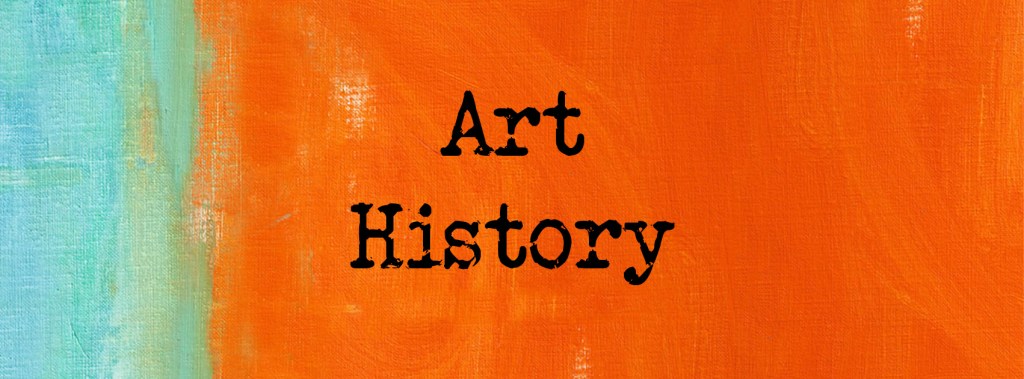

FEATURE Image: Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), L’église d’Auvers-sur-Oise, vue du chevet (“The Church at Auvers”), June 1890, oil on canvas, 94 cm x 74 cm (37 in x 29.1 in), Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), staying in Auvers starting on May 20, 1890 liked the country town with its artistic pedigree (Corot, Daubigny, Cézanne) and spoke of settling into permanent quarters in the village after renting an attic room in a local café. The artist continued about his experience at Auvers as he wrote: “[C]es toiles vous diront ce que je ne sais dire en paroles, ce que je vois de sain et de fortifiant dans la campagne” (“[T]hese canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.”) During his more than two months stay in Auvers, a small farm town about 20 miles west of Paris, the post-impressionist did more than 100 drawings and paintings of local landscapes, gardens, and village scenes such as this Catholic church. On the evening of July 27, 1890 Van Gogh had acquired a pistol and shot himself in the chest near the Auvers chateau. After languishing in pain for two days, he died on the morning of July 29, 1890. Vincent Van Gogh was 37 years old. Public Domain.

By John P. Walsh

In a peripatetic life, the last place where Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) lived was Auvers-sur-Oise, a small commune, a short distance northwest of Paris. Since Auvers was on a rail line in the orbit of Paris, Van Gogh moved to the small town with its farming community so he could live independently yet remain close to his art dealer younger brother Theo Van Gogh (1857-1891) who lived with his wife and family in the hustle and bustle of Paris. After leaving Saint-Paul Asylum, Saint-Rémy, where Van Gogh had admitted himself as a patient since May 1889, he traveled to the French capital in May 1890 where he visited Theo and Jo. He was then onwards to Auvers where, by arrangement of Theo, the artist was under the supervision of Dr. Paul Gachet (1828-1909), a mental health physician who was also an avid modern art collector and had his house, family and practice in the town. Vincent arrived to Auvers on May 20, 1890 and stayed in the Saint-Aubin hotel until he moved into a rented attic room in a café of Arthur Gustave Ravoux and his wife, Adeline Louise Touillet, who charged him three and a half francs per night for room and board. Located in Place de la Mairie, a 5-minute walk from the train station, the artist’s daily schedule involved rising at dawn and going outside to draw and paint.

After roaming the town where he made friends of villagers, visited Dr. Gachet’s, and journeyed into nearby farm fields, Van Gogh returned to Ravoux’s café for lunch that was served at noon. In the afternoon he might sometimes work in the “painters’ room” at the inn or visit with other painters staying at the inn, such as compatriot Anton Matthias Hirschig (1867-1939) and Spanish painter Martinez de Valdivielse. These acquaintances proved more significant for history insofar as they provided eyewitness testimony of Van Gogh’s death and funeral. Following dinner at Ravoux’s, Van Gogh climbed the inn’s simple staircase to his single room in the center of the attic landing and retired at about nine in the evening.

Van Gogh proved quite productive in Auvers, painting several notable canvasses in and around the town and countryside, particularly landscapes and other outdoor subjects en plein aire. In these two months, the painter produced 74 paintings and 33 drawings, including the portraits of Dr. Gachet and Adeline Ravoux, The Church of Auvers, and Field of Wheat with Crows. In a letter of around July 10, 1890, Van Gogh wrote to Theo and Jo that he painted three large canvases at Auvers since visiting them in Paris on July 6, 1890. During that visit the artist also met with Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and art critic Gabriel-Albert Aurier (1865-1892). In addition to Daubigny’s Garden, these large canvasses likely included Wheatfield with Crows and Wheatfields Thunderclouds (both Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam). Van Gogh described them as “immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies…searching to express sadness [and] extreme loneliness” (“immenses étendues de blés sous des ciels troublés… chercher à exprimer de la tristesse, de la solitude extreme”). See – https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let898/print.html – retrieved March 11, 2024.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent, as he did each day, went into the fields to paint. Though the artist appeared to be in good spirits, the artist shot himself later that day near the chateau after going for a walk towards evening. Though able to walk the 10 minutes back mortally wounded to Ravoux’s inn, he told them nothing upon entering the café. The Ravoux’s, sensing something was wrong, called for Mazery, the village doctor and Dr. Gachet. Though these doctors bandage the wound, Van Gogh’s condition is inoperable. In the hot attic room, Van Gogh suffered into the next day, when Theo was sent for. He arrived immediately on July 28 from Paris to be by his brother’s side. Van Gogh died the next morning of July 29, 1890. This suicide sent ripples of shock through the village, as some townspeople had witnessed these events. During my visit to Auvers in May 2005, after exiting Van Gogh’s room where he died, I told the innkeeper that the story was sad (“c’est triste”). She countered, “C’est emouvante” (“It’s moving”). Vincent was buried the next day, July 30, 1890, in Auvers’ new graveyard. His funeral was attended by Theo, Dr. Gachet, the Ravoux’s, assorted villagers, and friends from Paris. These last included artists Emile Bernard (1868-1941), Charles Laval (1862-1894), and Lucien Pissarro (1863- 1944), Camille Pissarro’s son. Petit boulevard art dealer and art materials supplier Julien (Père) Tanguy (1825-1894) was also in attendance. Van Gogh’s casket was strewn with yellow dahlias and sunflowers and Dr. Gachet gave remarks as did Theo Van Gogh. Later, in a letter to his wife, Theo wrote about the proceedings: “[Vincent] was buried in a sunny spot among the cornfields, and the cemetery does not have that unpleasant character of Parisian cemeteries.” (see- Kort geluk, 1999, p. 281). The mortal remains of Van Gogh were transported to the cemetery by a rented hearse from the next town because Auvers’ Catholic priest would not allow the community’s hearse to be used. A proposed church service was also cancelled. The homiletics were left to Dr. Gachet who said: “Vincent was an honest man and a great artist, and there were only two things for him – humanity and art. Art mattered to Vincent Van Gogh more than anything else and he will live on through it” (quoted in Complete Paintings, p. 719).

Three days after the funeral, Emile Bernard wrote to Aurier about “our dear friend Vincent.” Aurier had written in January 1890 about the intense fixity of Van Gogh’s art. The art critic conjectured that it may be the catalyst for change in French art. In his essay entitled Les Isolés: Vincent van Gogh published in Mercure de France, Aurier prophesied for an artist-savior figure: “A man must come, a Messiah, a sower of Truth, to rejuvenate our geriatric art, indeed perhaps the whole of our geriatric, feeble minded, industrial society” (quoted in Complete Paintings, p. 698). Van Gogh, aware of these statements, did not think he was Aurier’s man. On August 2, 1890 Emile Bernard wrote to Aurier: “On Sunday evening [Vincent] went out into the countryside near Auvers, placed his easel against a haystack and went behind the chateau and fired a revolver shot at himself. Under the violence of the impact (the bullet entered his body below the heart) he fell, but he got up again, and fell three times more, before he got back to the inn where he was staying (Ravoux, place de la Mairie) without telling anyone about his injury. He finally died on Monday evening, still smoking his pipe which he refused to let go of, explaining that his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity…. On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there. The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favorite color, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of as being in people’s hearts as well as in works of art….The sun was terribly hot outside. We climbed the hill outside Auvers talking about him, about the daring impulse he had given to art, of the great projects he was always thinking about, and of the good he had done to all of us. We reached the cemetery, a small new cemetery strewn with new tombstones. It is on the little hill above the fields that were ripe for harvest under the wide blue sky that he would still have loved…perhaps.Then he was lowered into the grave…Then we returned. Theodore Van Ghog [sic] was broken with grief; everyone who attended was very moved, some going off into the open country while others went back to the station…” (see – https://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/21/etc-Bernard-Aurier.htm – retrieved March 11, 2024.)

By contrast, Anton Hirschig, the Dutch artist who roomed next door to Van Gogh at Ravoux’s, wrote a letter much later, in 1911, to Albert Plasschaert (1874-1941) in which he recounted a more terrible scene following Van Gogh’s shooting himself. Hirschig wrote: “He lay in his attic room under a tin roof. It was terribly hot. It was August. He stayed there alone for some days. Perhaps only a few. Perhaps many. It seemed to me like a lot. At night he cried out, cried out loud. His bed stood just beside the partition of the other attic room where I slept: Isn’t there anyone willing to open me up! I don’t think there was anyone with him in the middle of the night and it was so hot. I don’t think I ever saw any other doctor like his friend the retired army doctor: It’s your own fault, what did you have to go kill yourself for? He didn’t have any instruments this doctor. He lay there until he died.”

Theo Van Gogh died in Holland on January 25, 1891, nearly 6 months to the day after Vincent’s death. Theo was buried in Holland but exhumed and reinterred next to his older brother Vincent’s grave in Auvers cemetery in 1914. While Vincent Van Gogh, the man, was never larger than life, as an artist he produced an explosion of life on paper and canvas. Van Gogh came to art late (30 years old in 1883) and produced incessantly for the next 7 years. His oeuvre was beautifully powerful, and none of it more remarkably for the future of modernism than that done in Auvers-sur-Oise in May to July 1890.

SOURCES –

Ingo F. Walther/Painer Metzger, Vincent Van Gogh The Complete Paintings, Benedikt Taschen, 1996.

Charles Harrison, Painting the Difference: Sex and Spectator in Modern Art, University of Chicago Press, 2006.

https://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/21/etc-Bernard-Aurier.htm – retrieved March 8, 2024

https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/agenda/expositions/van-gogh-auvers-sur-oise – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://vangoghroute.com/france/auvers-sur-oise/ https://vangoghroute.com/france/auvers-sur-oise/cemetery/ – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/bibliography.html – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/nl?page=3263&collection=451&lang=en – retrieved March 10, 2024.

https://www.vincentvangogh.org/portrait-of-dr-gachet.jsp – retrieved March 10, 2024.

http://www.vggallery.com/misc/archives/a_ravoux.htm – retrieved Match 11, 2024.

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/d0427V1962r – retrieved March 11, 2024

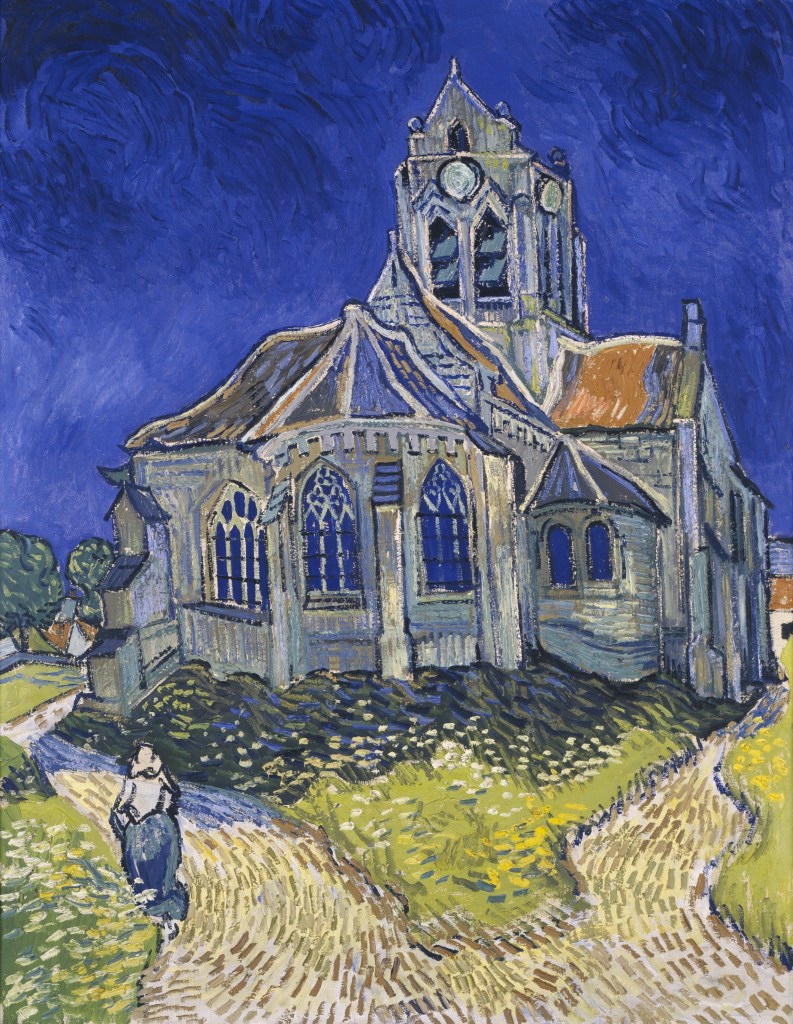

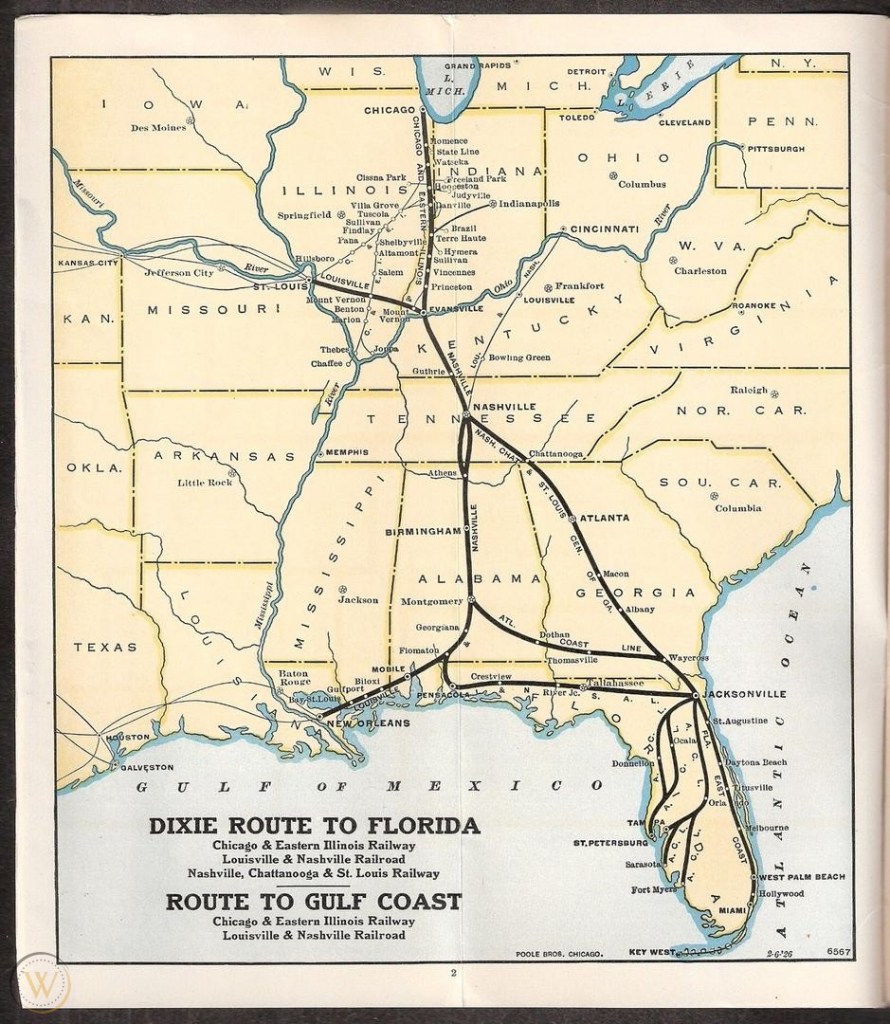

FEATURE Image: Dearborn Street Station in Chicago’s South Loop is an Italian brick Romanesque building with a granite base that was opened in 1885 at the cost of $500,000 (or almost $16 million in 2024). The architect was New York–based Cyrus L.W. Eidlitz who went on to build One Times Square (1904) in New York City from which the annual lit ball has dropped each New Year’s Eve since 1908. see – https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1885?amount=500000 – retrieved February 27, 2024. Author’s photograph, November 2017. 6.44mb

The Dearborn Street Station is Chicago’s oldest existing train station though it has not operated as one since 1971. It is a U-shaped Italian brick three-story Romanesque structure with a granite base that was originally 80 feet tall to the roof line.

Today’s flat roof is a modification by an unknown architect from its elaborate original hipped roof that was lost in a 1922 fire. The eye-catching Flemish tower, originally 166 feet tall, was also modified after the same conflagration. The station building marks the southern terminus of Dearborn Street which today extends about 4 miles to its northern terminus at the southern boundary of Lincoln Park. Author’s photograph.

The station’s frontage on Polk Street extends 212 feet. Originally the station extended 446 feet south along Plymouth Court with the train sheds 600 feet long with 8 tracks. The station’s train shed was demolished in 1976. In 1986 the station was converted to offices and shops (I had my Bank One branch in the Polk Street Station). Today it is the Dearborn Station Galleria in the South Loop Printing House Historic District.

Following demolition of the train sheds in 1976 the first phase of the Dearborn Park residential development south of the Dearborn Street Station building quickly sprang to life.

The Dearborn Station had 8 tracks that accommodated 12 coaches and engines with 122 trains arriving and departing daily. Train lines that entered this station included the Chicago & Eastern Illinois (1877-1976), Chicago and Atlantic Railway (later the Chicago and Erie Railroad) (1871-1941), the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe (1859-1996), the Louisville, New Albany & Chicago (or Monon) (1897-1971), Grand Trunk Western Railroad Company (1859-1991), the Wabash Railroad (1837-1964), the Erie Railroad (1832-1960) and the Chicago & Western Indiana (1880-present).

All lines operating into Dearborn Station, except for the Santa Fe (above), travelled over the C&WI.

Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz who built the Dearborn Street Station in Chicago in 1885 was from an influential American family of architects and builders—his father, Leopold Eidlitz (1823-1908), was a founder of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz is best known for designing One Times Square, the former New York Times Building, on Times Square in 1904. He also founded HLW International, one of the oldest architecture firms in the United States. The reconstruction of Dearborn Station in Chicago in 1923 following its devastating fire was done by an unknown architect two years after Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz’s death.

SOURCES:

AIA Guide to Chicago, 2nd Edition, Alice Sinkevitch, Harcourt, Inc., Orlando, 2004, p. 154.

History of Development of Building Construction in Chicago, Second Edition, Frank A. Randall, Revised and Expanded by John D. Randall, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1999, pp. 104-105 and 221-223.

Chicago’s Famous Buildings, 5th Edition, Franze Schulze and Kevin Harrington, The University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp. 89-90.

http://www.connectingthewindycity.com/2017/12/december-21-1922-dearborn-station.html – retrieved February 27, 2024.

FEATURE Image: Petrus Christus (c. 1395-1472), Pietà, c. 1455–60. 39 ¾ x 75 ½ inches, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

Flemish art, as the name suggests, originates in Flanders which includes the Low Countries (Netherlands and Belgium) as well as northeastern France. The centers of Flemish art in the 15th century are Brussels, Bruges, and, later, Antwerp as well as other cities such as Liège and Tournai. Though the area had been settled as early as the 6th century, great growth and prosperity came to the region starting in the 14th century. As an international trade center centered in Bruges and, following the silting up of Bruges’ port, in Antwerp starting around 1525, Flanders experienced an influx of tremendous wealth joined to its attendant political connections and power. Such factors led to a high demand for Flemish art locally and far beyond its borders to royal courts, churches and other public and private patrons having marked influence on the European Renaissance. These rich cultural conditions in and around Flanders provided incentive for leading Flemish art masters to perfect their art technique and create magnificent pictures, particularly altarpieces, and display the latest naturalist styles, delineated forms, and bright colors within a European context. Flemish art developed systematically including its use of oil painting. This newly discovered and controversial medium greatly affected Flemish paintings’ surface luminosity by way of its range of cool colors and its ability to be applied in smooth facile layers. Most of these noteworthy Flemish painters in the 15th century found positions at court or as officials in prosperous urban centers. They became leading citizens whose workshops trained artists and made artwork for public and private consumption which worked to assure Flemish art’s primacy for the Northern European Renaissance into the 16th century.

Melchior Broederlam was a painter in Ypres, Belgium, who entered the service as painter to Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1342-1402) in 1385 and was in Paris in the early 1390’s. The Champol Altarpiece is likely the earliest example of International Gothic in painting. The large diptych done for Philip the Bold is certainly painted by Broederlam.

Broederlam presents four stories in the life of the Virgin – The Annunciation, the Visitation, the Presentation in the Temple, and The Flight into Egypt. There is an attempt at realism by its placid gesturing figures in a landscape of crags and paths yet also flowers at the foot of these imposing structures. At the same time there remains a sense of unreality, that is, a theatrical or stage setting in its flat, unitive display.

From 1422 to 1424 Jan Van Eyck (or John of Bruges) worked for John III the Pitiless (1374–1425) of the House of Wittelsbach, who was bishop of Liège (1389–1418) as well as duke of Bavaria-Straubing and count of Holland and Hainaut (1418–1425). The artist was appointed court painter to Philip III the Good (1396-1467) who was born in Dijon and died in Bruges and who founded the Burgundian state that was France’s rival in the 15th century. Philip III was the most important of the Valois dukes of Burgundy.

Van Eyck lived in Lille between 1425 and 1429 but relocated to bustling Bruges in 1430 where he bought a house and lived until his death in 1441. On behalf of the Duke’s business concerns (including a secret marriage), Jan Van Eyck made trips to Spain and Portugal in 1427-28, and several others into the mid1430’s. There are many authenticated paintings by Jan Van Eyck, although Madonna of Chancellor Rolin is considered highly likely. The concept of composing the work to be divided into a shadowed interior and bright exterior landscape – and unified in the picture – is original. The contrasts of light, subject and form and their relation is appealing to the eye. The figures of the Virgin and the Child are delineated gently and beautifully for the donor, who is depicted behind a prayer desk, to adore. Like Italian master Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Van Eyck had many cultural interests and talents in the service of Philip III such as studies in anatomy, cartography, geometry and perspective that created the illusion of three-dimensional space. These artists’ common preoccupations and concerns in the arts united the Northern and Italian Renaissance more closely. If Van Eyck did not actually invent oil painting, his work perfected its techniques. Van Eyck’s abilities make him the major artist of the Early Netherlandish School whose position is challenged only by the Master of Flémalle (Robert Campin). It was painted for the chancellor of Philip III, Nicolas Rolin (c. 1376/80-1462) to decorate a personal chapel (Saint-Sébastien chapel) that he decided to build in 1426-1428 (completed in 1430) in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Châtel in Autun, a church destroyed in 1793.

Jan Van Eyck’s masterpiece is Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (1432), known as the Ghent Altarpiece, which he painted with his brother Hubert Van Eyck (c. 1370–1426). The Van Eycks’ artwork is known for its technical brilliance, intellectual complexity, and rich symbolism of which this very large (almost eight feet wide) and complex 15th-century polyptych is a prime testament. It was begun in the mid-1420s and completed by 1432. It marks a transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Northern European art. Its 22 panels opens and closes. When open, inside there are two rows of paintings. The middle section is Christ the King flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist. Other panels depict musicians, singing angels, and Adam and Eve. The center lower row depicts the Adoration of the Lamb with knights, hermits. judges and pilgrims who stream to behold the Lamb. In its 600-year history, there have been re-paintings, restorations and modern replacements (the original Judges panel was stolen in 1934). Little is known about Hubert Van Eyck to the point where he has been speculated in his obscurity to be a mythical figure, though this is quite unfounded. The painting was done for a nobleman’s family chapel in what become St. Bavo’s church in Ghent. The Eycks’ detail, fullness of form and luminous colors presents the mystery of the Mass whose subject is the miracle of the unity of heaven and earth in eternity. In contrast, the closed panel is beautifully calm and restrained in colors and composition. But it is just as masterful and, as it sits closed, offers a different mood for devotion.

The portrait is of the artist’s wife executed in Bruges. The Van Eycks married in 1439. Like his other portraits the sitter is turned three-quarters to the left. Painted 60 years before Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503), there are affinities between them – a placid enigmatic female sitter, leftward turn, hands crossed at the lap, a possible landscape background that in the Van Eyck has been repainted.

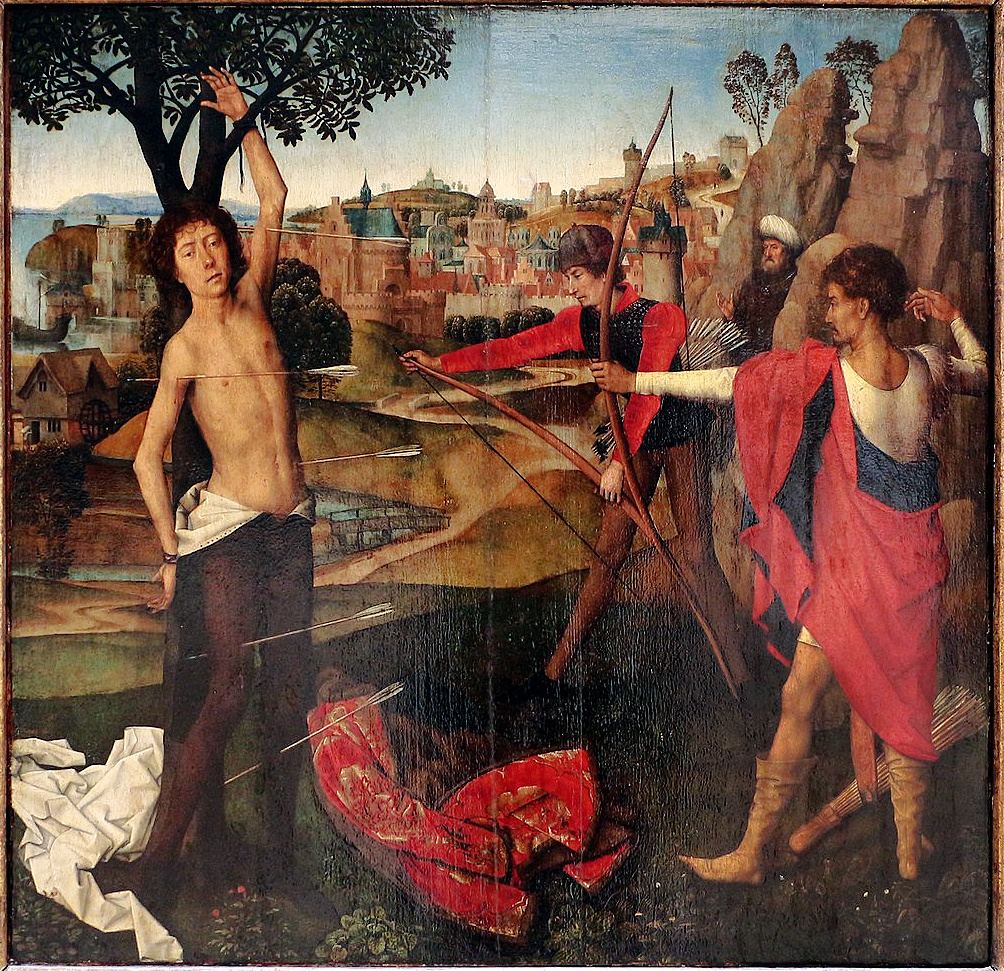

Following the death of Jan Van Eyck, Petrus Christus became the most important modern painter in Bruges who had settled there in 1444. The artwork was commissioned by the jewelers’ corporation in Bruges and depicts seventh century Saints Godeberta being given a ring by Saint Eligius to marry the Lord God as she decided to enter religious life. Though a religious painting, it is essentially a 15th century Flemish genre painting. And while not as graceful as Van Eyck’s artwork, the painting holds interest for its bold forms of figures and objects and the authority of a well-observed still life.

One of Petrus Christus’s most important works, the scene of the Deposition is poetically rendered in a mother’s lamentation over the dead Christ, her son, within the setting of a late afternoon landscape which is also perfectly rendered. The figures in the foreground are large and emphasize their placement in the space. The face of the Virgin constitutes the painting’s center. Holding the dead Christ in a sheet is NIcodemus and Joseph of Arimathea who asked Pilate for the body of Jesus so to bury him. The three figures who stand apart from the narrative’s central figures are depicted with equal stylistic power and whose strained grief they share.

The painterly style of the Master of Flémalle is earlier than Jan Van Eyck yet also progressing a naturalism that is realistic and of ordinary folk. The Master of Flémalle has been identified by consensus as Robert Campin whose pupils were Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464) and Jacques Daret (c. 1404- c. 1470). Campin is known to have lived and worked in Tournai, Belgium. This imposing, cruelly exact image depicts the corpse of one of the two criminals crucified with Jesus. Executed in the workshop of Robert Campin in Tournai around 1420 – around the same time as the Van Eycks’ Ghent Altarpiece – the fragment is all that remains though copies of the rest exist that show the Deposition and John the Baptist. The painting presents the bad thief in a corporeal monumentality next to an embossed gold background which is a legacy of medieval art. The painting’s unwavering physicality, however, is 15th century modern. The well-constructed faces of the two observers are modeled by shadows as foreshortening suggests movement. The lower left of the picture at the thief’s broken legs reveals, as Delevoy states, “the perspective of a landscape that is concisely constructed, geometric, and intellectual.”

The Nativity is the most famous work of the Master of Flémalle (Robert Campin). The single panel combines dreamed up images, and meticulous objective observation and rational knowledge to depict three episodes – (1) the legend of the midwives, (2) adoration of the shepherds, (3) the Nativity. The wooden stable, with its ox and ass, has a broken wall and holes in the roof. The Virgin dressed in white is kneeling with her hands held up in adoration as the Christ Child lies naked on the ground. Joseph is depicted as an old man and holds a lit candle that he shelters. The legend of the midwives is an apocryphal Gospel tale regarding Joseph’s anxiety during the birth and summoning these midwives with complicated headdresses. The stable door is swung open and three shepherds enter behind Mary and Joseph. Four angel figures hover above the scene holding strips of parchment with messages. There is an extensive, condensed, and detailed winter landscape in the background with a wide, curving road and castle perched on a hill.

Placid depiction of the Annunciation at the moment when the angel Gabriel alights in the Virgin’s chamber. The setting is a middle-class home and Mary is, for the moment, still completely unaware of the mystery that will now be told to her. A miniature figure with a cross comes through the oculus above the angel. The objects in the room– a lily, an immaculate towel, an extinguished taper– may be symbolic but certainly work to hold realistic tactile value. The robes in the foreground, one red, the other light blue, provide focus for the painting’s harmony and color. The Master of Flémalle experiments with Renaissance applications of perspective, depth, proportion (foreshortening) with material objects such as open shutters, an open door (left panel), and an unforgiving diagonal of the room’s bench. These material objects in varying perspectival space as well as varying light sources give the painting complexity. The right panel depicts old Joseph in his carpenter workshop. The left panel shows the painting’s donors on their knees witnessing this remarkable scene through the open door. There is speculation that the Master of Flémalle had painted the center panel and, as buyers showed interest, these donors commissioned the wings that were painted by workshop artists such as, likely, young Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400–1464) and Jacques Daret (ca. 1404–1468).

Rogier Van der Weyden was a major artist in Flanders in the mid15th century. He was a pupil of Robert Campin, the Master of Flémalle, from which he imbued his realistic, ordinary naturalism with, what Murray said, was “more emotion, warmth and sensitiveness.” Insofar as the power of his artistic technique, Van der Weyden is a peer of Jan Van Eyck. Van der Weyden’s colors are cooler than Van Eyck’s and he subordinates his technical abilities to display the feelings of his paintings’ subject matter, typically religious. In terms of composition the striking difference between Van Eyck and Van der Weyden is that Van Eyck crafts a setting for his panorama of iconic vignettes while Van der Weyden paints flat-on action, often intensely emotional – all of which contributes to the artwork as a whole. Both Van Eyck’s Adoration of the Lamb and Van der Weyden’s The Deposition or Descent from the Cross are the most influential Flemish paintings of the mid15th century. Van der Weyden’s overall oeuvre makes him, arguably, 15th century Flemish art’s most influential figure.

Van der Weyden married a woman from Brussels and relocated to that growing and prosperous city in the marshes of Flanders in 1426. By the mid1430’s Van der Weyden was the City Painter and did work for the Burgundian Court. In 1450 the artist traveled to Rome and Florence where the early Italian Renaissance was in full swing and whose art greatly influenced the Flemish master’s art through the 1450s and into the 1460’s. The Triptych of the Seven Sacraments Altarpiece was a return to the artist’s native city as it was painted for the Bishop of Tournai whose coat of arms appear on the upper portions of each panel. Set in the impressive Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in Brussels, the painting presents profound religious content in a finely drafted and colorful work – the left panel depicting the sacraments of initiation (baptism, confession and confirmation), the center of the Eucharist under a giant cross, and the right panel depicting the sacraments of ordination, marriage, and last rites.

Rogier van der Weyden painted several superb and sensitive portraits including Charles the Bold (Berlin), Le Grand Bâtard of Burgundy (Brussels), a Lady (National Gallery of Art, D.C.). Francesco d’Este was an Italian who received an education at the Burgundian Court. The d’Este family in Ferrara, Italy, was all-powerful when Rogier Van der Weyden visited there in 1450, though this portrait is done later. The sitter holds a hammer and ring whose significance is not explained with certainty.

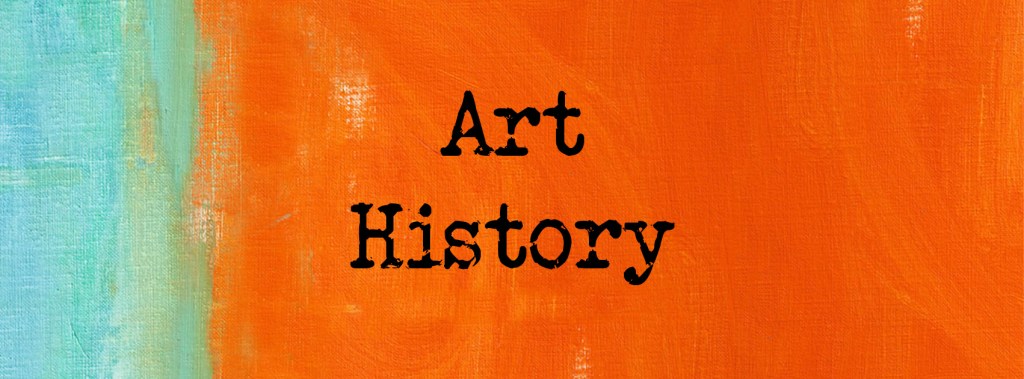

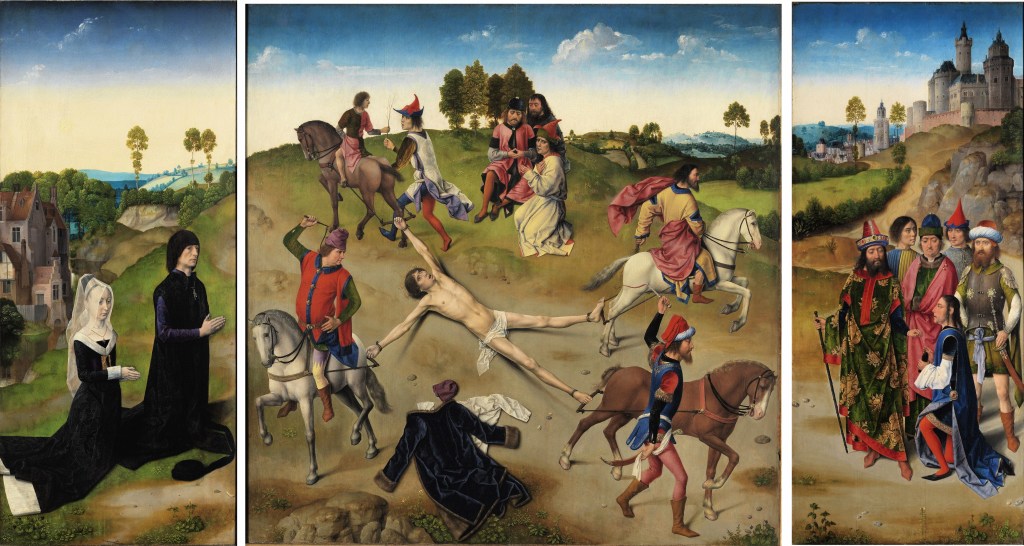

Dieric Bouts was born in Haarlem, the Netherlands, around 1415, where little is known of his early life. Before 1448 Bouts was working in Louvain where he married a wealthy Catharina Van der Brugghen and would work there until his death in 1475. Bouts’ finest paintings are characterized by their subtle depiction of colors and light on semi-inert and dignified and emotionally calm figures in detailed and delicately beautiful landscapes. Rogier van der Weyden influenced Bouts’ earlier work (Bouts may have trained with him in Brussels) in its greater emotionalism. In the year of Van der Weyden’s death the Brotherhood of the Blessed Sacrament of Louvain commissioned an altarpiece to place in St. Peter’s Church in Louvain. The artist worked with theologians to establish an iconography for the Eucharist which he then translated to contemporary Louvain with an exceptional plasticity whose result is that it is one of 15th century Europe’s greatest artworks. Jan Van Eyck’s influence is manifest in Bouts’ elegant intellectuality (in turn, Bouts was influential on 15th century German painting). Its perspectival calculus is matched to shapes and forms that convey emotion within the work’s compositional rigor. The head of Christ whose raised hand blesses the bread occupies the center of the artwork as the apostles gather in groupings around a table which itself develops within the room’s structure. The four side panels are scenes from the Old Testament transmitted likely by those same Catholic theologians who advised Bouts as to Biblical precedents to Christ’s Last Supper – here, the Feast of the Passover, Elijah in the Desert, the Gathering of Manna, and Abraham and Melchizedek. In 1472, Bouts was appointed city painter in Louvain, an honorary title at a time when the city was undergoing massive urban development. After Bouts’ wife died in 1473, the artist remarried in 1474 but died himself in 1475. Bouts was buried beside his first wife in the Franciscan church in Louvain. His sons, Dieric and Albrecht, were artists who continued the family tradition into the 16th century.

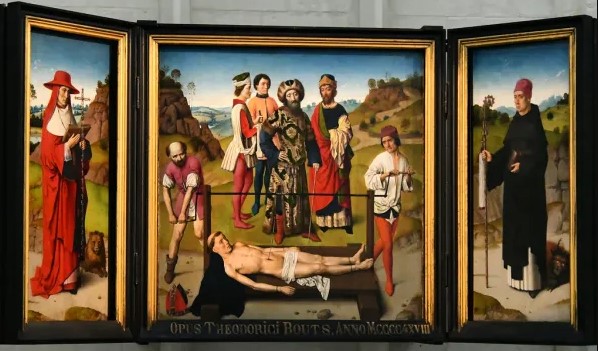

Unusual for Bouts this painting depicts the torture of martyrdom. There are many figures named Hippolytus in the early church. According to Prudentius’ 5th century account, one was the martyr Hippolytus who was dragged to his death by wild horses. The account led to this Hippolytus being considered the patron saint of horses. The square format panel preferred by Bouts depicts the martyrdom from above with foreshortened horsemen shown from the front. It is the first Flemish painting to depict movement not simply by using gesture. As Delevoy assesses, “The success of the picture lies in its timeless definition, its iconographic originality, its pictorial poetry, its popular feeling, its anecdotal interest.”

This is one of two paintings that is certain to be by Bouts (the other is Five Mystic Meals). It was commissioned in 1468 by a Louvain magistrate for the new city hall and intended to be an ambitious project on the Last Judgment. But it remained uncompleted at Bouts’s death. Panels representing heaven and hell survive and these two thematically related panels illustrating an episode from the legend of the Holy Roman emperor Otto III (980-1002). A 13th century chronicle tells how the Empress falsely accused an innocent man of a crime and persuades Otto and his court to behead him (left panel). The second panel shows the beheaded man’s wife, convinced of her husband’s innocence, approaching Otto’s throne with his head and a hot iron. Calling on God as judge, the Empress’s guilt is revealed and the royal is burned at the stake depicted in the distance. There is no lack of drama in the skillfully drawn episodes with elongated bodies, fanciful clothes, and unique facial expressions. The central focus of the panels is neither Otto nor his court but the put-upon widow of the innocent man murdered by the state through duplicity.

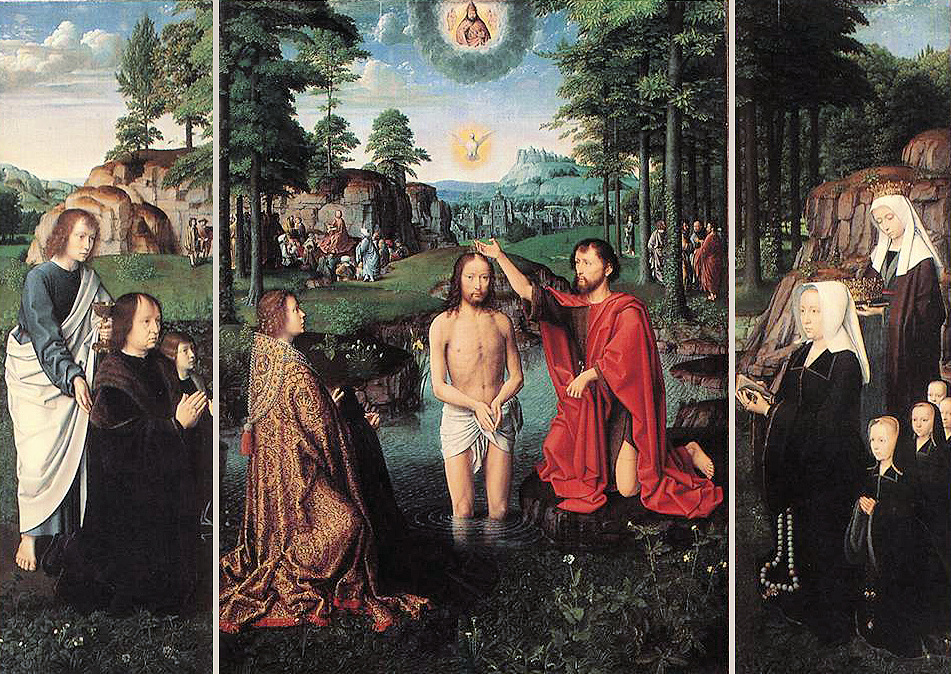

Hugo Van Der Goes (c.1440-1482) was the most important Netherlandish painter working in Ghent after Jan Van Eyck. A Ghent native, Van der Goes was in a guild there in 1467 and rose to its leadership between 1473 and 1475. Soon afterwards, the artist completed the Portinari Altarpiece for an Italian who was then residing in the Netherlands. The painting was sent immediately to Florence. Though not having the opportunity to have any great influence in the Netherlands, the Flemish 15th century art practice of cool colors and exquisite oil technique impressed the Renaissance Italians, notably Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494). Also, its immense size – eight feet tall and 19 feet wide – and its virtuosity made an impact. By synthesizing Van der Weyden’s drama and sensuous expression and Bouts’ three-dimensional space, Van der Goes gives increased everyday tangible reality to his sacred subjects. Sharing Broederlam’s inquiries for visual appearances, Van Der Goes’ artwork creates new forms, types, and the impetus behind them based in popular sentiments and an edgy mysticism. So, in a 15th century sort of way, this is not your father’s Nativity (i.e, Master of Flémalle’s in 1420). It is ponderable, dense, significantly tactile and spatially voluminous. The Virgin, in prayer and in maternal caress, is in the exact center of the immense triptych. Also in the circle are St. Joseph, the shepherds, angels in the air and the Christ Child. The painting is a masterpiece of contrasts – between religious, secular, and rustic architectures; heavenly and earthly figures; peace and agitation; filled space and void; warm tones and cool colors.

Around 1475 Hugo Van Der Goes became a lay brother in an Augustinian Priory, the Roode Cloister. Founded in 1367, the cloister is on the southeastern edge of modern Brussels. The artist continued to paint and receive visitors there, traveled to Louvain and Cologne, and died in 1482.

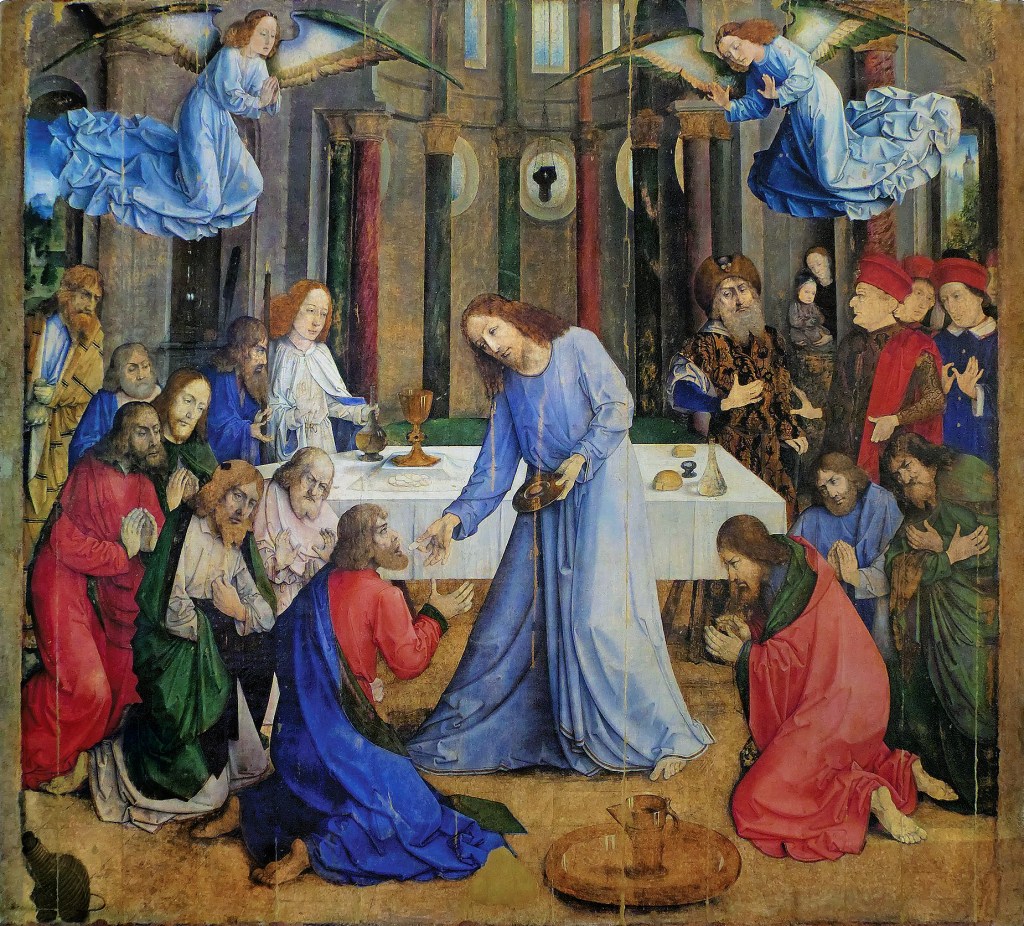

Justus van Ghent was a master in Antwerp in 1460 and in Ghent four years later where he met Hugo van der Goes. By the time of his death Justus van Ghent was in Rome, a city that was increasingly attracting international artists, including from northern Europe. Van Ghent was in Urbino where he painted Institution of the Eucharist in Urbino. The commission was originally given to Italian artist Piero della Francesca (1415-1492) and its predella (the altarpiece’s painting at its lower edge) was completed by Uccello (1397-1475).

Hans Memling was a German, born near Frankfurt-am-Main. Memling was likely a student of Rogier van der Weyden and completely Netherlandish in his artistic style. Memling lived in Bruges and became a citizen in 1465. By 1480 the successful artist was one Bruges denizen who was paying the city’s largest amount of taxes. Though not innovative, Memling’s artwork depicts calm and peaceful figures full of piety. Memling also painted portraits successfully. Examples of his artwork are in collections all over the world.

Gerard David was a Dutch painter born in Oudewater. David was in Bruges by 1484. He was the last major painter from Bruges and painted pious pictures in a gentle Netherlandish style right before the rise of a new Italianate style in Antwerp. David traveled to Antwerp in 1515 and joined the Guild but returned to Bruges and died there in 1523. Though many pictures are attributed to David, the pair of Justice paintings are certainly his.

A Dictionary of Art and Artists, Peter and Linda Murray, Penguin Books; Revised,1998.

Early Flemish Painting, Robert L. Delevoy, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1963.

https://www.britannica.com/summary/Jan-van-Eyck – retrieved February 5, 2024.

https://www.britannica.com/summary/Philip-III-duke-of-Burgundy – retrieved February 5, 2024.

https://www.uffizi.it/en/online-exhibitions/portinari-triptych#2 – retrieved February 6, 2024.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5I_MKCs8Zo – retrieved February 7, 2024.

https://sammlung.staedelmuseum.de/en/work/the-bad-thief-to-the-left-of-christ – retrieved February 4, 2024.

https://www.mleuven.be/en/even-more-m/last-supper – retrieved February 2, 2024.

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061856 – retrieved January 29, 2024

https://www.codart.nl/guide/agenda/dieric-bouts-creator-of-images/ – retrieved January 29, 2024

https://collectie.museabrugge.be/en/collection/work/id/O_SJ0188_I – retrieved January 29, 2024

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/110001938?rndkey=20120109&pos=145&pg=10&rpp=15&ft=*&high=on– retrieved January 29, 2024

https://www.wga.hu/html_m/m/master/flemalle/nativity/nativi_.html – retrieved January 29, 2024

FEATURE image: September 1994. Montaña de Oro State Park. San Luis Obispo/Los Osos, CA. 80%

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) gravesite, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Mass. Emerson has been called “the most iconoclastic thinker in nineteenth century America” (Geary’s Guide to the World’s Great Aphorists, p. 83). A minister by inkling and training, Emerson graduated from Harvard University in 1821 and became an ordained minister in 1829. He abandoned traditional Christianity and writing sermons after his first wife’s death in 1831 and, traveling to England and back, embraced Transcendentalism and writing essays exploring the nature of life and death. These he read aloud to enthusiastic audiences around the country. Emerson published his first book, Nature, in 1836 and a second and third volume of essays in 1841 and 1844. From 1842 to 1844, Emerson was editor of The Dial, a Transcendentalist journal. During his lifetime, Emerson gave thousands of lectures upsetting more than a few with his views on, for example, Native American policy (he wrote against Cherokee removal in the 1830’s) and slavery (he condemned the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and supported abolitionist political candidates in New England).

July 1989. Henry D. Thoreau (1817-1862) gravesite, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Mass. Thoreau, a naturalist and Transcendentalist writer, moved into his one-room cabin on Walden Pond in 1845. Thoreau had a close relationship with fellow Transcendentalist philosopher and writer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who is also buried in this cemetery. Thoreau’s essay Civil Disobedience published in 1849 argued in favor of citizen disobedience against an unjust state.