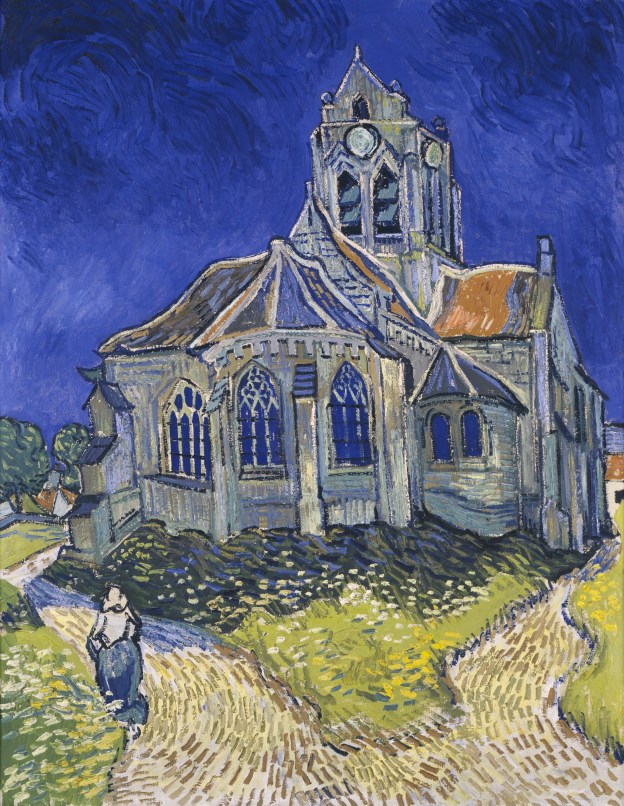

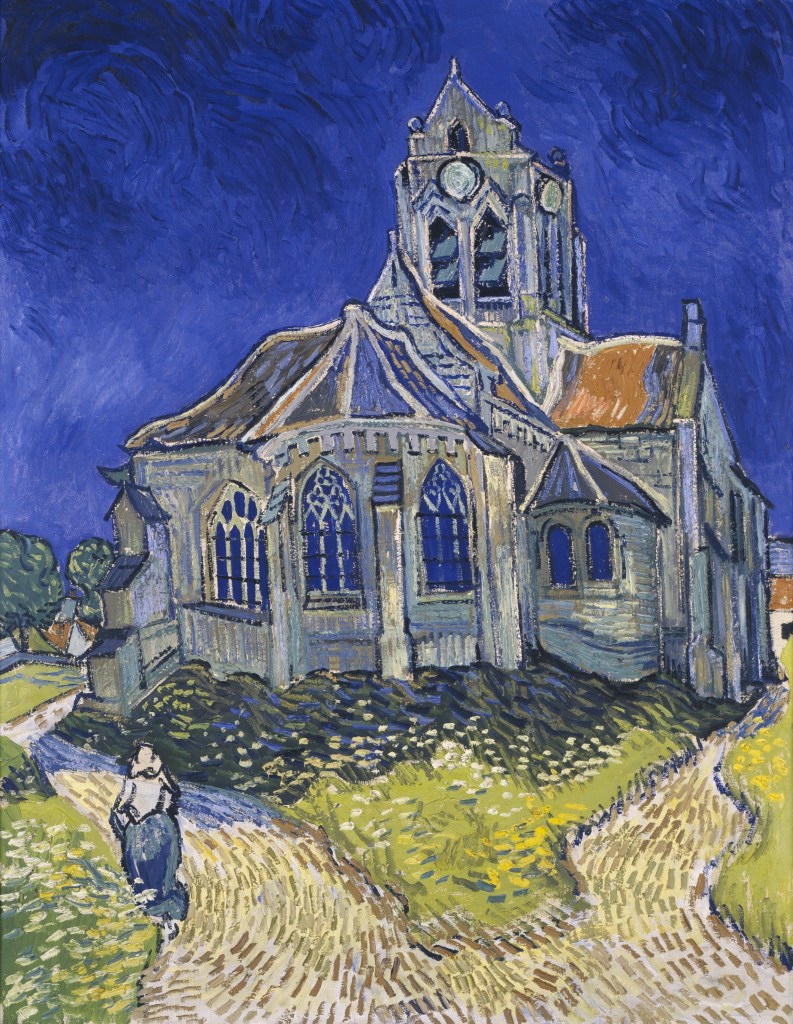

FEATURE Image: Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), L’église d’Auvers-sur-Oise, vue du chevet (“The Church at Auvers”), June 1890, oil on canvas, 94 cm x 74 cm (37 in x 29.1 in), Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), staying in Auvers starting on May 20, 1890 liked the country town with its artistic pedigree (Corot, Daubigny, Cézanne) and spoke of settling into permanent quarters in the village after renting an attic room in a local café. The artist continued about his experience at Auvers as he wrote: “[C]es toiles vous diront ce que je ne sais dire en paroles, ce que je vois de sain et de fortifiant dans la campagne” (“[T]hese canvases will tell you what I can’t say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.”) During his more than two months stay in Auvers, a small farm town about 20 miles west of Paris, the post-impressionist did more than 100 drawings and paintings of local landscapes, gardens, and village scenes such as this Catholic church. On the evening of July 27, 1890 Van Gogh had acquired a pistol and shot himself in the chest near the Auvers chateau. After languishing in pain for two days, he died on the morning of July 29, 1890. Vincent Van Gogh was 37 years old. Public Domain.

By John P. Walsh

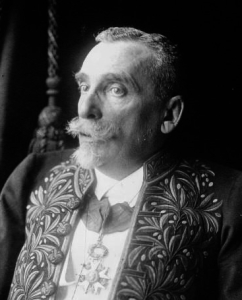

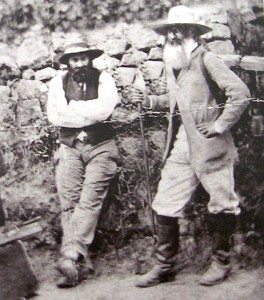

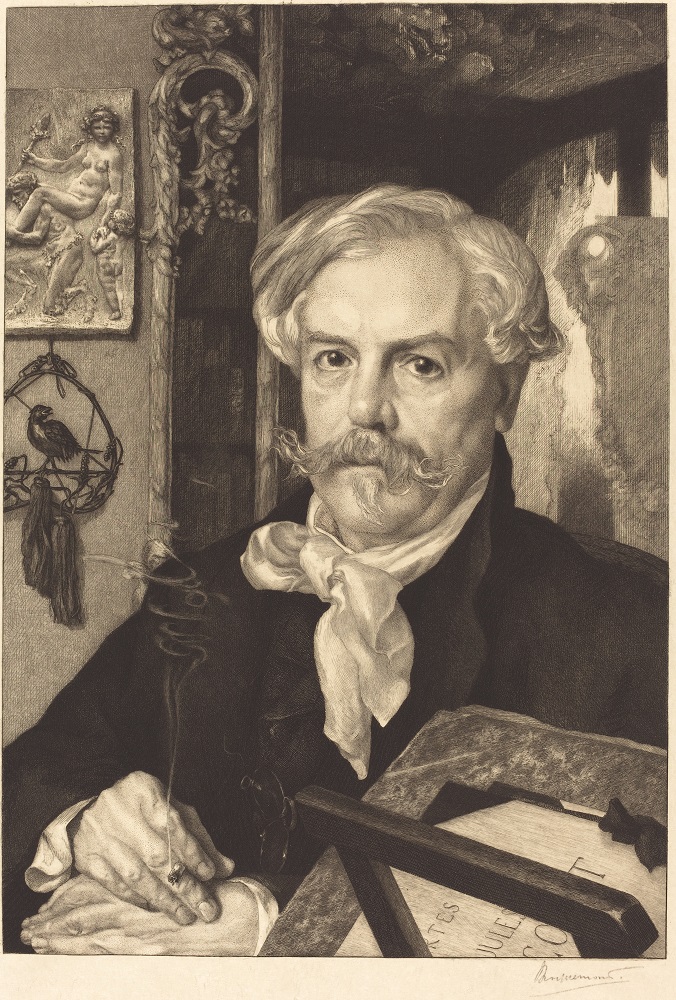

In a peripatetic life, the last place where Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) lived was Auvers-sur-Oise, a small commune, a short distance northwest of Paris. Since Auvers was on a rail line in the orbit of Paris, Van Gogh moved to the small town with its farming community so he could live independently yet remain close to his art dealer younger brother Theo Van Gogh (1857-1891) who lived with his wife and family in the hustle and bustle of Paris. After leaving Saint-Paul Asylum, Saint-Rémy, where Van Gogh had admitted himself as a patient since May 1889, he traveled to the French capital in May 1890 where he visited Theo and Jo. He was then onwards to Auvers where, by arrangement of Theo, the artist was under the supervision of Dr. Paul Gachet (1828-1909), a mental health physician who was also an avid modern art collector and had his house, family and practice in the town. Vincent arrived to Auvers on May 20, 1890 and stayed in the Saint-Aubin hotel until he moved into a rented attic room in a café of Arthur Gustave Ravoux and his wife, Adeline Louise Touillet, who charged him three and a half francs per night for room and board. Located in Place de la Mairie, a 5-minute walk from the train station, the artist’s daily schedule involved rising at dawn and going outside to draw and paint.

After roaming the town where he made friends of villagers, visited Dr. Gachet’s, and journeyed into nearby farm fields, Van Gogh returned to Ravoux’s café for lunch that was served at noon. In the afternoon he might sometimes work in the “painters’ room” at the inn or visit with other painters staying at the inn, such as compatriot Anton Matthias Hirschig (1867-1939) and Spanish painter Martinez de Valdivielse. These acquaintances proved more significant for history insofar as they provided eyewitness testimony of Van Gogh’s death and funeral. Following dinner at Ravoux’s, Van Gogh climbed the inn’s simple staircase to his single room in the center of the attic landing and retired at about nine in the evening.

Van Gogh proved quite productive in Auvers, painting several notable canvasses in and around the town and countryside, particularly landscapes and other outdoor subjects en plein aire. In these two months, the painter produced 74 paintings and 33 drawings, including the portraits of Dr. Gachet and Adeline Ravoux, The Church of Auvers, and Field of Wheat with Crows. In a letter of around July 10, 1890, Van Gogh wrote to Theo and Jo that he painted three large canvases at Auvers since visiting them in Paris on July 6, 1890. During that visit the artist also met with Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and art critic Gabriel-Albert Aurier (1865-1892). In addition to Daubigny’s Garden, these large canvasses likely included Wheatfield with Crows and Wheatfields Thunderclouds (both Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam). Van Gogh described them as “immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies…searching to express sadness [and] extreme loneliness” (“immenses étendues de blés sous des ciels troublés… chercher à exprimer de la tristesse, de la solitude extreme”). See – https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let898/print.html – retrieved March 11, 2024.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent, as he did each day, went into the fields to paint. Though the artist appeared to be in good spirits, the artist shot himself later that day near the chateau after going for a walk towards evening. Though able to walk the 10 minutes back mortally wounded to Ravoux’s inn, he told them nothing upon entering the café. The Ravoux’s, sensing something was wrong, called for Mazery, the village doctor and Dr. Gachet. Though these doctors bandage the wound, Van Gogh’s condition is inoperable. In the hot attic room, Van Gogh suffered into the next day, when Theo was sent for. He arrived immediately on July 28 from Paris to be by his brother’s side. Van Gogh died the next morning of July 29, 1890. This suicide sent ripples of shock through the village, as some townspeople had witnessed these events. During my visit to Auvers in May 2005, after exiting Van Gogh’s room where he died, I told the innkeeper that the story was sad (“c’est triste”). She countered, “C’est emouvante” (“It’s moving”). Vincent was buried the next day, July 30, 1890, in Auvers’ new graveyard. His funeral was attended by Theo, Dr. Gachet, the Ravoux’s, assorted villagers, and friends from Paris. These last included artists Emile Bernard (1868-1941), Charles Laval (1862-1894), and Lucien Pissarro (1863- 1944), Camille Pissarro’s son. Petit boulevard art dealer and art materials supplier Julien (Père) Tanguy (1825-1894) was also in attendance. Van Gogh’s casket was strewn with yellow dahlias and sunflowers and Dr. Gachet gave remarks as did Theo Van Gogh. Later, in a letter to his wife, Theo wrote about the proceedings: “[Vincent] was buried in a sunny spot among the cornfields, and the cemetery does not have that unpleasant character of Parisian cemeteries.” (see- Kort geluk, 1999, p. 281). The mortal remains of Van Gogh were transported to the cemetery by a rented hearse from the next town because Auvers’ Catholic priest would not allow the community’s hearse to be used. A proposed church service was also cancelled. The homiletics were left to Dr. Gachet who said: “Vincent was an honest man and a great artist, and there were only two things for him – humanity and art. Art mattered to Vincent Van Gogh more than anything else and he will live on through it” (quoted in Complete Paintings, p. 719).

Three days after the funeral, Emile Bernard wrote to Aurier about “our dear friend Vincent.” Aurier had written in January 1890 about the intense fixity of Van Gogh’s art. The art critic conjectured that it may be the catalyst for change in French art. In his essay entitled Les Isolés: Vincent van Gogh published in Mercure de France, Aurier prophesied for an artist-savior figure: “A man must come, a Messiah, a sower of Truth, to rejuvenate our geriatric art, indeed perhaps the whole of our geriatric, feeble minded, industrial society” (quoted in Complete Paintings, p. 698). Van Gogh, aware of these statements, did not think he was Aurier’s man. On August 2, 1890 Emile Bernard wrote to Aurier: “On Sunday evening [Vincent] went out into the countryside near Auvers, placed his easel against a haystack and went behind the chateau and fired a revolver shot at himself. Under the violence of the impact (the bullet entered his body below the heart) he fell, but he got up again, and fell three times more, before he got back to the inn where he was staying (Ravoux, place de la Mairie) without telling anyone about his injury. He finally died on Monday evening, still smoking his pipe which he refused to let go of, explaining that his suicide had been absolutely deliberate and that he had done it in complete lucidity…. On the walls of the room where his body was laid out all his last canvases were hung making a sort of halo for him and the brilliance of the genius that radiated from them made this death even more painful for us artists who were there. The coffin was covered with a simple white cloth and surrounded with masses of flowers, the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favorite color, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of as being in people’s hearts as well as in works of art….The sun was terribly hot outside. We climbed the hill outside Auvers talking about him, about the daring impulse he had given to art, of the great projects he was always thinking about, and of the good he had done to all of us. We reached the cemetery, a small new cemetery strewn with new tombstones. It is on the little hill above the fields that were ripe for harvest under the wide blue sky that he would still have loved…perhaps.Then he was lowered into the grave…Then we returned. Theodore Van Ghog [sic] was broken with grief; everyone who attended was very moved, some going off into the open country while others went back to the station…” (see – https://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/21/etc-Bernard-Aurier.htm – retrieved March 11, 2024.)

By contrast, Anton Hirschig, the Dutch artist who roomed next door to Van Gogh at Ravoux’s, wrote a letter much later, in 1911, to Albert Plasschaert (1874-1941) in which he recounted a more terrible scene following Van Gogh’s shooting himself. Hirschig wrote: “He lay in his attic room under a tin roof. It was terribly hot. It was August. He stayed there alone for some days. Perhaps only a few. Perhaps many. It seemed to me like a lot. At night he cried out, cried out loud. His bed stood just beside the partition of the other attic room where I slept: Isn’t there anyone willing to open me up! I don’t think there was anyone with him in the middle of the night and it was so hot. I don’t think I ever saw any other doctor like his friend the retired army doctor: It’s your own fault, what did you have to go kill yourself for? He didn’t have any instruments this doctor. He lay there until he died.”

Theo Van Gogh died in Holland on January 25, 1891, nearly 6 months to the day after Vincent’s death. Theo was buried in Holland but exhumed and reinterred next to his older brother Vincent’s grave in Auvers cemetery in 1914. While Vincent Van Gogh, the man, was never larger than life, as an artist he produced an explosion of life on paper and canvas. Van Gogh came to art late (30 years old in 1883) and produced incessantly for the next 7 years. His oeuvre was beautifully powerful, and none of it more remarkably for the future of modernism than that done in Auvers-sur-Oise in May to July 1890.

SOURCES –

Ingo F. Walther/Painer Metzger, Vincent Van Gogh The Complete Paintings, Benedikt Taschen, 1996.

Charles Harrison, Painting the Difference: Sex and Spectator in Modern Art, University of Chicago Press, 2006.

https://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/21/etc-Bernard-Aurier.htm – retrieved March 8, 2024

https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/agenda/expositions/van-gogh-auvers-sur-oise – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://vangoghroute.com/france/auvers-sur-oise/ https://vangoghroute.com/france/auvers-sur-oise/cemetery/ – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/bibliography.html – retrieved March 8, 2024.

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/nl?page=3263&collection=451&lang=en – retrieved March 10, 2024.

https://www.vincentvangogh.org/portrait-of-dr-gachet.jsp – retrieved March 10, 2024.

http://www.vggallery.com/misc/archives/a_ravoux.htm – retrieved Match 11, 2024.

https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/d0427V1962r – retrieved March 11, 2024