FEATURE image: Detail, Queen Elizabeth I. Ditchley portrait. Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, 1592.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Captain Thomas Lee in Irish Dress, oil on canvas, 1594 (purchased 1980), Tate Britain.

Captain Thomas Lee (c.1551-1601) had his portrait painted by 33-year-old Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (Bruges, 1561-1636) in London in 1594. Captain Lee was 43 years old and had worked as a military adventurer for English colonization in Ireland since the early 1570’s.

The young artist was the son of Gheeraerts the Elder (c. 1520–c. 1590), a painter and printmaker associated with the Tudor court in the late 1560’s and 1570’s. Fleeing religious persecution in Flanders, Gheeraerts the Elder arrived into England with his 7-year-old son Marcus in 1568. In 1577, Gheeraerts the Elder had likely returned to Flanders.

By 1594, when the portrait of Captain Lee was made, Gheeraerts the Younger was a rising young contemporary artist working in Elizabeth I’s Tudor court. Sir Roy Strong, the English art historian who served as director of the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is unequivocal about Gheeraerts the Younger’s artistic importance to English art history. Strong wrote that Gheeraerts is “the most important artist of quality to work in England in large-scale between (Hans) Eworth (c. 1520 – 1574) and (Anthony) van Dyck (1599-1641).”1

In addition to a discussion of the early painting of Captain Lee, a complete collection of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’s 33 art works– including signed and dated works, documented and dated works, inscribed and dated works, and inscribed and undated works– is included in this post following this introduction.

Social contract: Marriages of court artists in late-16th-century Tudor England.

At 22 years old in 1583, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’s world in and around London was ideally enclosed by marriage to the sister of talented Tudor court painter John De Critz (c.1555-c.1641). De Critz, like his new brother-in-law Gheeraerts the Younger, was a child expatriate from Flanders to England in 1568.2

In 1571 Gheeraerts the Elder had married his son’s future wife’s sister, making father and son Gheeraerts also eventually brothers-in law.3

Over two decades later, in 1602, Gheeraerts the Younger’s sister married the court artist Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617).4

This was typical social behavior at the Tudor court where many active artists were connected by ties of marriage, family, and artistic training as well as shared European origin.

In Gheeraerts the Younger’s circle, for instance, John De Critz was apprenticed to the wealthy portrait painter Lucas de Heere (1534-1584) who may also have helped train Gheeraerts the Younger. De Heere – like Gheeraerts the Younger and De Critz – was a religious refugee to England from Flanders.

Isaac Oliver, Gheeraerts the Younger’s other brother-in-law, studied under leading Tudor portrait miniaturist and goldsmith Nicholas Hilliard (c.1547-1619). 5 Roy Strong as Director of the National Portrait Gallery in London links Hilliard to Gheeraerts by way of the supreme artistic quality found in both of these contrasting artists’ masterpieces.6

One remarkable technical innovation that the young artist applied in his portraits was the use of stretched canvas in place of wood panel that allowed for larger and lighter surface areas on which to paint and more easily transport pictures of the grand gentlemen and ladies of the time.

By way of marriage to an Irish Catholic woman, Captain Thomas Lee became a man of considerable property in Ireland. Captain Lee had separated from his wife by the time of his portrait. The next year -– in 1595 –- Lee married an Englishwoman. Over the decades, Captain Lee’s military reputation became one of an enfant terrible in Ireland which did not mellow over time. Powerful friends looked to explain Thomas’s frequent reckless political and military behavior. It was justified as the occupational hazard of a longtime English soldier in Ireland.

Planning and posing of Captain Lee’s portrait.

Lee posed for Gheeraerts when the captain was straight off the battlefield from Ulster chieftain Aodh Mag Uidhir (Hugh Maguire, d. 1600) and in London for delicate negotiations.

To presumably express Thomas’s faithful service to the Crown, the portrait includes a Latin inscription in the tree that refers to Mucius Scaevola (c. 500 BC), an ancient perhaps mythical Roman fighter who remained loyal to Rome even after he was captured by mortal enemies.

Captain Thomas Lee was related to Sir Henry Lee as paternal half cousins. Sir Henry was Queen Elizabeth I’s Champion for almost 25 years until his retirement in 1590. In that capacity, Henry was the creator of the stunning imagery for her publicly-popular Accession Day festivals that he annually planned. Along with Gheerearts the Younger’s Elizabethan allegorical portrait Lady in Fancy Dress (The Persian Lady) (#30 below) and the Ditchley portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (#31 below) — both painted in the early 1590s — Henry, who remained active and influential in political affairs, may have helped devise the symbolism in Captain Lee’s portrait. The portrait also came from Ditchley, Sir Henry Lee’s timber-framed family house set in the wooded farmsland of north Oxfordshire.

While the painting’s landscape where Captain Lee stands is likely a representation of Ireland’s wild landscape, Henry Lee’s symbolism may provide other subtle and humorous features.

Troublesome Thomas, for example, stands under an oak, which may refer to Sir Henry’s political protection but also that these trees are prone to dangerous lightning strikes.

The final seven years of Captain Thomas Lee’s life iterated a legendary standard: at times negotiating with or killing Irish enemies he also served time in prison in Ireland on a charge of treason. Ultimately, Sir Henry could not save his familial junior– in 1601 Thomas faced execution in England for treason against Elizabeth I.

English colonial rule tightens in 17th century Ireland.

English power became increasingly absolute in 17th century Ireland.

In the 1590’s, the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland believed turning their backs on the mostly Catholic natives was the most effective governing strategy. While an oath of allegiance to the Crown remained law to divest Irish rebels of their property to English rule, it was not vigorously applied until the arrival in 1604 into Ireland of Lord Deputy Arthur Chichester (1563-1625).

The 1590’s continued to implement England’s new plantation system in Ireland which amounted to confiscating Irish property for English and Scottish settlers. While this provided quick and lucrative rewards for the conquerors, the political situation was not free of ambiguity. English laws were attacked by Irish chiefs seeking protection under older common law.

Protestant settlers had their own uneasy relationship with the English Crown who, in turn, fought a tug of war with an English Parliament.

About half of settlers in Ulster were Presbyterians who were dissenters from the English church which itself was at war with Anglo- and Gaelic Irish Catholics. Moreover, London viewed new Protestant landowners in Ireland –- such as Captain Thomas Lee –- with no less suspicion as despoiled Catholics. The Crown believed that the new Protestant vanguard in Ireland had power to usurp the island’s treasure more readily than pillaged Catholics who could, ironically perhaps, be better disposed to the idea of royal governance.7

While Thomas Lee’s special status is expressed in the painting’s lace embroidery on his rolled-up shirt and inlaid pistol and Northern Italian-made helmet, the Captain is dressed as a common foot-soldier who traveled through Ireland lightly armed. Captain Lee is also, both seriously and humorously, barelegged.

Sir Henry Lee must have been one of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’s earliest patrons, as the Ditchley collection had several portraits which can be ascribed to the artist.8

FOOTNOTES:

- Strong, Roy, The English Icon: Elizabethan & Jacobean Portraiture, The Paul Mellon Foundation for British Art London Routledge and Kegan Paul Limited New Haven Yale University Press, 1969, p.22.

- Ibid. p.259.

- Hearn, Karen, Marcus Gheeraerts II: Elizabethan Artist, In Focus (Tate Publishing), 2003, p. 11ff.

- Strong, p.269.

- Hearn, p.130.

- Strong, p.23.

- See Roger Chauviré, A Short History of Ireland, New American Library, 1965; T.W. Moody & F.X. Martin, editors, The Course of Irish History, Mercier Press, Cork, 1978; http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gheeraerts-portrait-of-captain-thomas-lee-t03028 – retrieved May 28, 2017.

- The Captain Thomas Lee portrait was first recorded at Ditchley by Vertue in 1725 who noted there a portrait of ‘Lee in Highlanders Habit leggs naked a target & head piece on his left hand his right a spear or pike. Ætatis suae.43.ano.Dni 1594’.

1. SIGNED AND DATED WORKS (8 works):

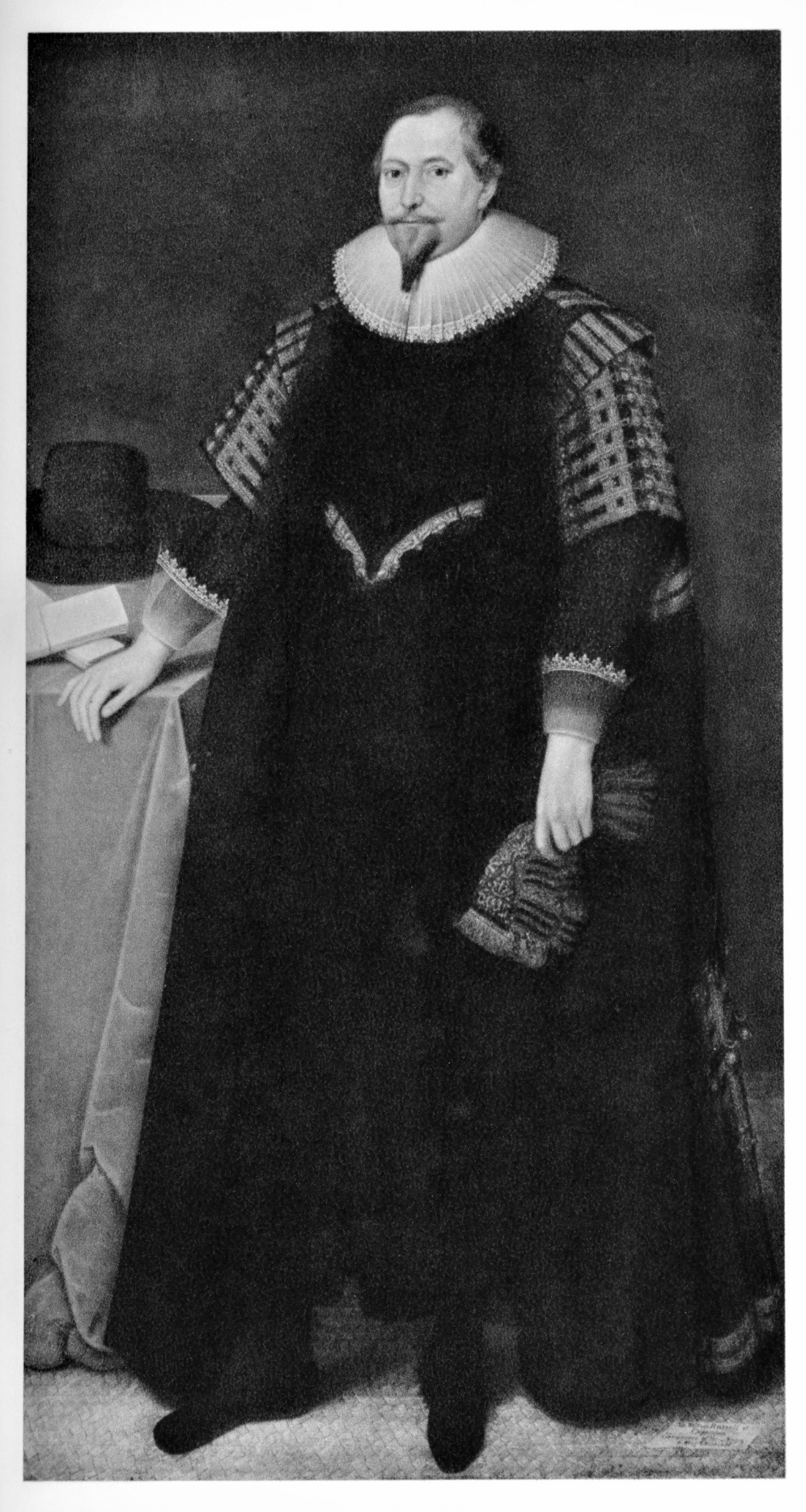

1 – Marcus Gheeraerts The Younger, Louis Frederick, Duke of Württemberg, 1608, oil on canvas, 225.1 x 113.1 cm, St James Palace. Probably painted for James I though first recorded in Charles II’s collection. (Strong 255, The English Icon).

Gheeraerts II painted portraits of several foreign dignitaries on their visits to the English court. Louis Frederick, Duke of Württemberg visited James I in London for three months in the latter part of 1608 and likely the artist produced this work at that time.

2 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, William Camden, 1609, oil of panel,, 76.2.x 58.5 cm, Bodleian Library, Oxford. Given to the Schools by Camden Professor (1622-1647) Degory Whear. (Strong 256).

3 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Lucy Davis, Countess of Huntingdon, 1623, oil on panel, 76.8 x 62.3 cm, Private Collection. (Strong 257).

4 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, William Pope, 1st Earl of Downe, 1624, oil on panel, 62.3.x 47.1 cm, Trinity College, University of Oxford. It was presented to Trinity College in 1813 by Henry Kett. (Strong 258).

5 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Elizabeth Cherry, Lady Russell, 1625, oil on canvas, 194.5 x 105.6 cm, The Duke of Bedford. This painting has been at Woburn Abbey since 1625. (Strong 259).

6 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir William Russell, 1625, oil on canvas, 195.6 x 111.8 cm, The Duke of Bedford. Always at Woburn Abbey. (Strong 260).

7 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Richard Tomlins, 1628, oil on panel, 111.8 x 83.9 cm. The Bodleian Library, Oxford. It was in the Library in 1759. (Strong 261).

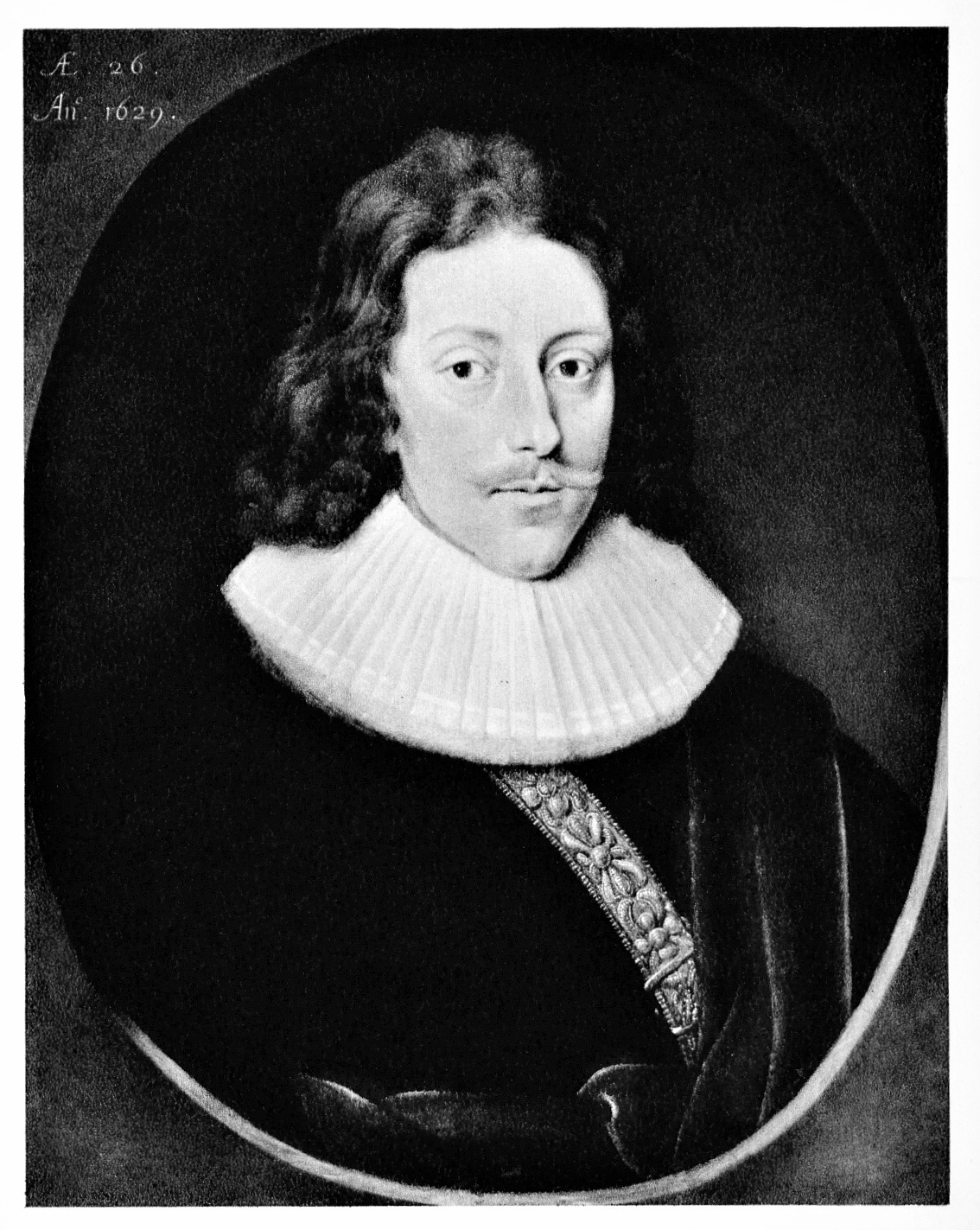

8 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Anne Hale, Mrs. Hoskins, 1629, oil on panel, 111.8 x 82.7 cm. Jack Hoskins Master, Esq. The painting remains in the family. (Strong 262). With detail.

2. DOCUMENTED AND DATED WORKS (3 works):

9 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Barbara Gamage, Countess of Leicester, and her children, 1596, oil on canvas, 203.2 x 260.3 cm, The Viscount De L’Isle. Always at Penshurst Place near Tonbridge, Kent, 32 miles southeast of London; first recorded 1623. (Strong 263).

10 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, William, 2nd Lord Petre, 1599, oil on panel. 111.8 x 90.2.cm. The Lord Petre; custody of the Essex County Record Office. (Strong 264).

11 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Katherine Somerset, Lady Petre, 1599, oil on panel, 111.8 x 90.2 cm. The Lord Petre. Always at Ingatestone Hall, the 16th century manor of the Barons Petre in Essex, England. Queen Elizabeth I spent several nights there in 1561. (Strong 265).

3. INSCRIBED AND DATED WORKS (18 works):

12 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Unknown Lady (Mary Rogers, Lady Harington), 1593, oil on panel, 114.3 x 94 cm, Tate (purchased 1974). The identity for the sitter is speculative, although her age (23 years old) is inscribed. It is one of the earliest known portraits by Gheeraerts. (Strong 266).

Detail, Unknown Lady (Mary Rogers, Lady Harington), 1593. The sitter is identified in part by the clothes she wears: the distinctive black and white pattern on her dress heralds the Harington coat of arms. The sitter is 23 years old and her portrait may have been painted in connection with a visit to Kelston (The Harington homestead) in 1592 by Queen Elizabeth. The Latin inscription in the painting reads, “I may neither make nor break” a dramatic phrase whose meaning is no longer clear.

13 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Captain Thomas Lee in Irish Dress, oil on canvas, 1594 (purchased 1980), Tate Britain. (Strong 267). With detail.

14 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Francis Drake, oil on canvas, 1594. Versions at National Maritime Museum, Greenwich and Lt.- Col. Sir geirge Tapps-Gervis-Meyrick.

15 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Unknown Man (Called the Earl of Southampton), 1599, location unknown. (Strong 269).

16 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Unknown Lady, 1600, oil on panel, The Lord Talbot de Malhide. (Strong 270).

17 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Henry Lee, oil on canvas, 1600, private collection on loan since 2008 to Tate Britain.

Sir Henry Lee (1533–1611), a Tudor Court favorite under Elizabeth I, was appointed as Queen’s Champion and Master of the Armoury. In that capacity, Sir Henry organised the annual public Accession Day festivals in honor of the queen. He commissioned the famous Ditchley portrait of Elizabeth I by Gheeraerts for his house at Ditchley in Oxfordshire. In 1597 he was made a Knight of the Garter and in Gheeraerts‘s portrait wears that order’s gold chain and bejeweled medal of St George slaying the dragon. (Strong 271).

18 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Henry Lee in Garter Robes, 1602, oil on canvas, 216.2 x 137.2 cm. Always at Ditchley until 1933. Today at The Armourers & Brasiers’ Company of the City of London. Founded in 1322, the livery company was awarded its first Royal Charter in 1453 from King Henry VI. In 1708 the Armourers joined with the Brasiers and received its current charter from Queen Anne. (Strong 272).

Detail, Sir Henry Lee in Garter Robes, 1602. One of Gheeraerts II’s finest portraits, Sir Henry Lee is a former man of action, whose old head is remarkably shrewd.

19 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Christophe de Harlay, Comte de Beaumont, 1605, oil on canvas, The Marquess of Salibury.

The Comte de Beaumont was the French ambassador to England at a time when the Kings of England and France were looking in their own ways for a diplomatic solution to the religious controversies in Europe. The painting was made for Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, a politician who had won James I’s trust. (Strong 273).

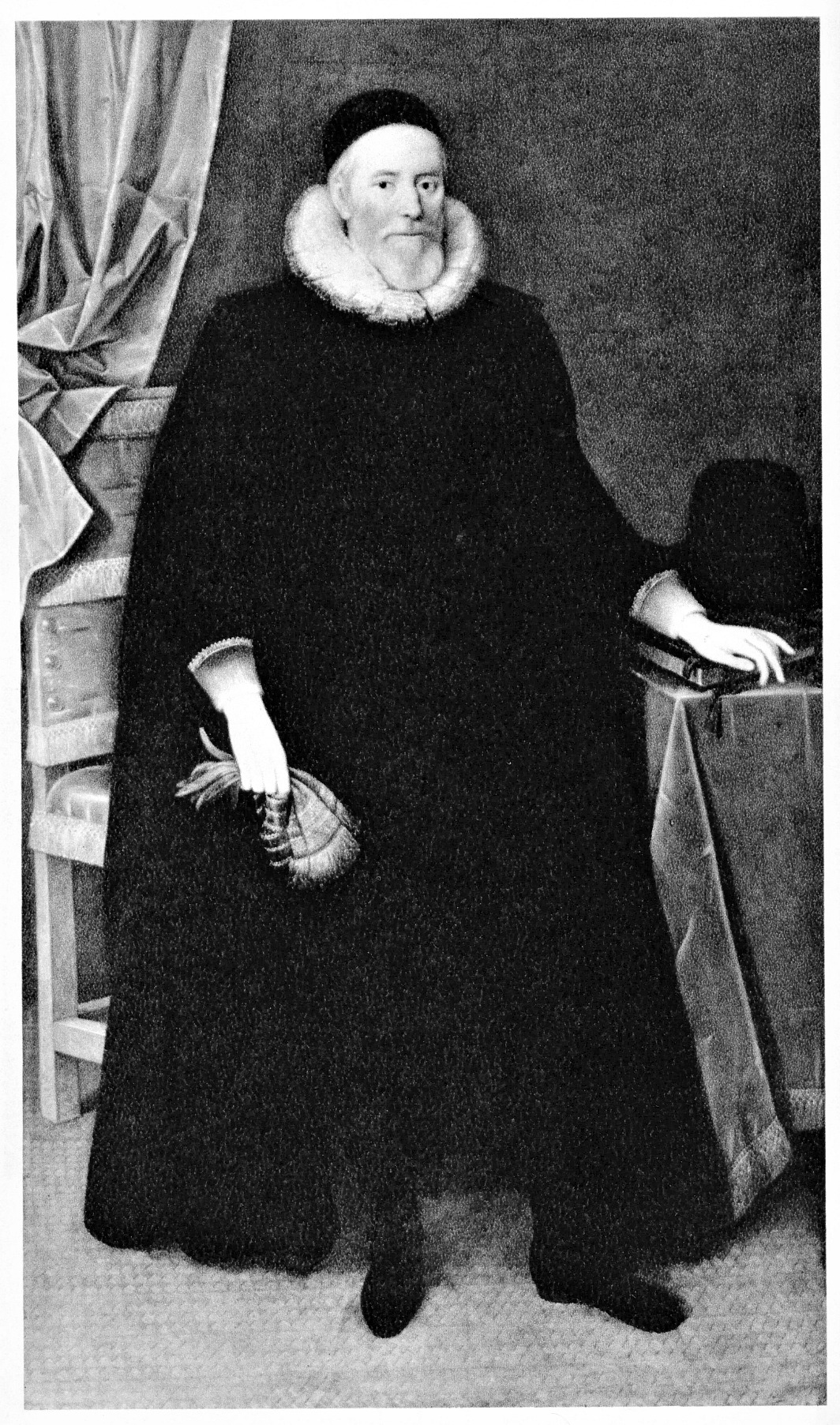

20 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Alexander Seton 1st Earl of Dunfermline, 1606.

Alexander Seton, 1st Earl of Dunfermline (1555–1622), a Scot, was regarded as one of the finest legal minds of his time. Seton served as Lord President of the Court of Session (top judge) from 1593 to 1604, Lord Chancellor of Scotland (top presiding officer of state) from 1604 to 1622 and Lord High Commissioner to the Scottish Parliament. (Strong 274).

21 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Anne of Denmark, 1614, oil on panel, 109.4 x 87.3 cm, Windsor Castle.

At 15 years old, Anne married the future James I of England in 1589. The Queen consort bore James three children who survived infancy, including the future Charles I (reigned 1625-1649).

Once fascinated with his bride, observers regularly noted incidents of marital discord between the dour and ambitious James and his independent and self-indulgent wife.

Before she died in 1619 the royal couple led mainly separate lives. (Strong 275).

22 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Ulrik, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, 1614, oil on canvas, 211.2 x 114.3 cm, The Duke of Bedford.

Prince Ulrik of Denmark, (1578–1624) was the second son of King Frederick II of Denmark and his consort, Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow.

As second-born Ulrick bore the merely titular rank of Duke of Holstein and Schleswig although he later became Administrator of Schwerin.

After his sister Anne became Queen of England, Ulrik was godfather to Princess Mary. (Strong 276).

23 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir John Kennedy, oil on canvas, 1614, The Duke of Bedford. Upon James I’s accession, Elizabeth Brydges — Maid of Honour of Queen Elizabeth I — married Sir John Kennedy, one of the king’s Scotch attendants. This occured at Sudeley Manor in Gloucestershire.

Chandos appears to have opposed the match, and it was rumored in early 1604 that Sir John Kennedy had a wife living in Scotland. James I wrote to Chandos (February 19, 1603 or 1604) entreating him to overlook Sir John’s errors because of his own love for his attendant.

Elizabeth Brydges apparently left her husband and desired to have the matter legally examined. As late as 1609 the legality of the marriage had yet to be decided.

Lord Chandos declined to aid his cousin, and Sir John Kennedy’s wife died deserted and in poverty in 1617. (Strong 277).

24 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Catherine Killigrew, Lady Jermyn, 1614, oil on panel, 73.7 x 57.2 cm, Yale Center for British Art. (Strong 278).

Catherine Killigrew was 35 years old when she sat for this portrait. The wife of an MP as well as the mother of three children, Catherine was the daughter of Sir William Killigrew (d. 1622) who was a courtier to Queen Elizabeth I and to King James I. Her father, Sir William, served as Groom of the Privy Chamber. (Strong 278).

25 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, probably Mary (née Throckmorton), Lady Scudamore, oil on panel, 1615, 45 in. x 32 1/2 in. (1143 mm x 826 mm), National Portrait Gallery, London, purchased 1859.

The sitter, once wrongly identified as the Countess of Pembroke, is likely Lady Scudamore though about whom little is known. The portrait is likely for the occasion of her son’s marriage (John, later Viscount Scudamore) to Elizabeth Porter of Dauntsey, Wiltshire.

The wreath of flower and inscribed motto ‘No Spring Till now,’ suggest the hope that this marriage must have represented within the family. (Strong 279).

26 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Henry Savile, 1621, 216.2 x 127 cm, Bodleian Library, Oxford. Gift from the sitter’s widow, 1622.

Sir Henry Savile (1549-1622) was an enterprising Bible scholar. When his qualifications did not meet the standards for the role of Provost of Eton, he had Queen Elizabeth I waive the college’s rules for him.

As Warden of Merton — a post secured with the help of influential friends — he was unpopular with faculty and students though the college itself flourished.

Sir Henry’s brother was a powerful lawyer who helped guide his brother’s career which included knighthood in 1604. (Strong 280).

27 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Henry Savile, 1621, oil on canvas, 1621, 203.7 x 122 cm, Eton College. A second smaller copy of the Bible scholar and college administrator. (Strong 281).

28 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, 1628, oil on panel, 68.5 x 48.2 cm, Philip Yorke.

Under King James I, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1580 –1630), founded Pembroke College, Oxford, in 1624. In 1623 the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays was dedicated to him and to Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery (the later 4th Earl of Pembroke), his brother.

A bookish man, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke was engaged to be married three times. The first engagement was to Elizabeth Carey in 1595. Elizabeth was the granddaughter of the Lord Chamberlain who ran Shakespeare’s company. William simply refused to marry her. In 1597 William was engaged a second time. This time it was to Bridget de Vere. As William found her dowry arrangements to be unsatisfactory, negotiations dragged out to a tiresome point where the match became unacceptable.

In 1600 William impregnated a mistress at court whom he refused to marry. The child was born and died soon after. Following this episode, William and the mistress (Mary Fitton) were barred from court.

In 1604 William married Mary Talbot. Their children both died in infancy. At the same time, William was having an extra-marital affair with his cousin, Lady Mary Wroth, which produced two illegitimate children.

A lively patron of the arts, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke died suddenly in 1630 at 50 years old. He is buried in Salisbury Cathedral in the family vault at the foot of the altar. (Strong 282).

29 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Charles Hoskins, 1629, oil on panel, 66.1 x 52.7 cm, Jack Hoskins Master. Esq. (Strong 283).

30 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Lady in Fancy Dress (The Persian Lady), 1590s, oil on panel, 216.5 x 135.3 cm, Hampton Court.

First recorded in the collection of Queen Anne but believed to be part of the Royal Collection before that time, in the cartouche the sonnet reads: “The restless swallow fits my restless minde, Instill revivinge still renewinge wronges; her Just complaintes of cruelty unkinde, are all the Musique, that my life prolonges. With pensive thoughtes my weeping Stagg I crowne whose Melancholy teares my cares Expresse; hes Teares in sylence, and my sighes unknowne are all the physicke that my harmes redresse. My only hope was in this goodly tree, which I did plant in love bringe up in care: but all in vaine, for now to late I see the shales be mine, the kernels others are. My Musique may be plaintes, my physique teares If this be all the fruite my love tree beares.”

Lady in Fancy Dress is a good example of Elizabethan allegorical portraiture. Importantly, the painting may be related to the Ditchley portrait of Elizabeth I (Strong 285) as well as the portrait of Captain Thomas Lee (Strong 267 ). These three portraits may be connected in some way to the entertainment given by Sir Henry Lee, the Queen’s Master of the Armouries and Champion of the Tilt, when the Queen visited Ditchley in 1592. (Strong 284).

Queen Elizabeth I is standing on a map of England. Detail from The Ditchley Portrait of Elizabeth I by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger in 1592.

Detail of a bejeweled fan in Queen Elizabeth I’s right hand from The Ditchley Portrait of 1592 by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. In the decade before The Ditchley Portrait Gheeraerts the Elder, Marcus II’s father, had painted a full- length oil on panel portrait of Elizabeth I. In the ensuing handful of years, practical technical innovation in art is in evidence in the Elizabethan court — the the son’s oil portrait of the same royal personage was able to be produced on canvas on a much larger scale.

Detail of the beautiful garment and accessories.

Detail, Queen Elizabeth I. Ditchley portrait. Three fragmentary Latin inscriptions in the painting have been interpreted as: “She gives and does not expect”; “She can, but does not take revenge”; and, “In giving back, she increases.”

An inscribed sonnet, whose author is not known, takes the sun as its subject. At some later date the canvas was cut more than 7 centimeters fragmenting the final words of the each line.

31 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Queen Elizabeth I (“The Ditchley Portrait”), oil on canvas, 1592, 95 in. x 60 in. (2413 mm x 1524 mm). National Portrait Gallery, London. Bequeathed by Harold Lee-Dillon, 17th Viscount Dillon, 1932.

Queen Elizabeth was nearly 60 years old when this portrait was made. It is traditionally understood to have been painted on the Queen’s visit to Ditchley, the timber-framed family house in north Oxfordshire of Sir Henry Lee (1533-1611).

Like John II Walshe (d.1546/7) of Little Sodbury, Gloucestershire, who was the King’s Champion to Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII, Henry Lee served at that standard for Queen Elizabeth from 1570 until his retirement about two years before this painting was made.

Ditchley once provided lodging and access to the royal hunting ground of Wychwood Forest. (Strong 285).

32 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Sir Henry Lee, 1590s, oil on canvas, 117 x 86.4 cm, The Ditchley Foundation. Always at Ditchley. The painting and inscribed verses memoralize an incident where Bevis – Lee’s dog – saved his master’s life. “More faithfull then favoured…” (Strong 286).

33 – Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Michael Dormer, mid 1590s, oil on canvas, 122 x 91.5 cm, J.C. H. Dunlop, Esq. There are Latin inscriptions which surround and are written across the globe and shield. (Strong 287).

The social and cultural world of Sir Henry Lee once again influences the young artist’s portrait of Michael Dormer, who was an Oxfordshire neighbor to Sir Henry. In Dormer’s three-quarter-length portrait, the right hand is posed similarly to Thomas Lee’s portrait. As Captain lee’s portrait is the centerpiece of this post’s explorations,it may be said with Michael Dormer’s this post has traveled full circle around Marcus Gheeraerts II’s verifiable portraiture in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.

Here then concludes the complete collection of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’s signed and dated works (Strong 255-262); inscribed and dated works (Strong 266-283); and, inscribed and undated works (Strong 284-287). Not included here are works dated and attributed to the artist (Strong 288-294) and attributed and undated (Strong 295-313). The last group includes several well-known portraits including William Cecil, Lord Burghley, c. 1595, in the National Portrait Gallery (Strong 295) and Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, c. 1596, in collection of the Duke of Bedford. (Strong 300).

CAPTION NOTES:

Strong 255 – Hearn, Karen, Marcus Gheeraerts II, Elizabethan Artist (In Focus series), Tate Publishing, 2002, p. 29.

Strong 264 and 265 – http://www.ingatestonehall.com/

Strong 266- http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gheeraerts-portrait-of-mary-rogers-lady-harington-t01872

Strong 271- http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gheeraerts-sir-henry-lee-l02883

Strong 272- http://www.armourershall.co.uk/armourers-hall

Strong 277 – http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/BRYDGES.htm#Catherine BRYDGES (C. Bedford)

Strong 278- http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1669266

Strong 279 – http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw05683/Probably-Mary-ne-Throckmorton-Lady-Scudamore#sitter

Strong 280 – https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/sir-henry-savile-15491622-228559/search/actor:gheeraerts-the-younger-marcus-1561156216351636/view_as/list/page/2; White, Henry Julian (1906). Merton College, Oxford. pp. 93–94; http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/savile-henry-ii-1549-1622; https://www.oxforduniversityimages.com/results.asp?image=BOD000038-01; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Savile_(Bible_translator)

Strong 282 – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Herbert,_3rd_Earl_of_Pembroke

Strong 284 – https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/406024/portrait-of-an-unknown-woman; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artists_of_the_Tudor_court; http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gheeraerts-portrait-of-captain-thomas-lee-t03028; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Lee_(army_captain); https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:PKM/icon4

STRONG 285 – John II Walshe (d.1546/7) of Little Sodbury, Gloucestershire, was King’s Champion at the coronation of Henry VIII in 1509 and was a great favorite of the young king’s. Transactions of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Vol.13, 188/9, pp. 1–5, Little Sodbury”. Bgas.org.uk. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-19; Sir H Lee – Butler, Katherine (2015). Music in Elizabethan Court Politics. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 129–42. ISBN 9781843839811.; Ditchley once provided lodging and access to the royal hunting ground of Wychwood Forest. – timber-framed family house in classic north Oxfordshire wooded farmland, – https://web.archive.org/web/20070404233018/http://www.ditchley.co.uk/page/37/ditchley-park.htm; Inscriptions – http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02079/Queen-Elizabeth-I-The-Ditchley-portrait#description; http://npg.si.edu/exhibit/britons/briton1.htm; Hearn, Karen, Marcus Gheeraerts II, Elizabethan Artist (In Focus series), Tate Publishing, 2002, p. 31.

STRONG 287 – Hearn, Karen, Marcus Gheeraerts II, Elizabethan Artist (In Focus series), Tate Publishing, 2002, p. 24.