Photographs and Text by John P. Walsh.

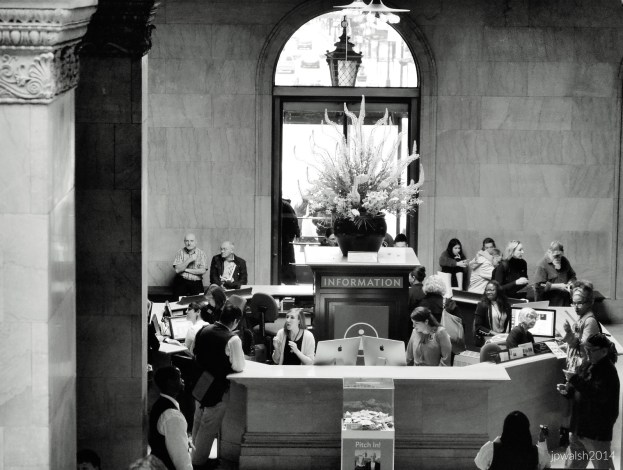

FEATURE image: Main Lobby. The Art Institute of Chicago (2014).

Photographs:

Photographs and Text by John P. Walsh.

FEATURE image: Main Lobby. The Art Institute of Chicago (2014).

Photographs:

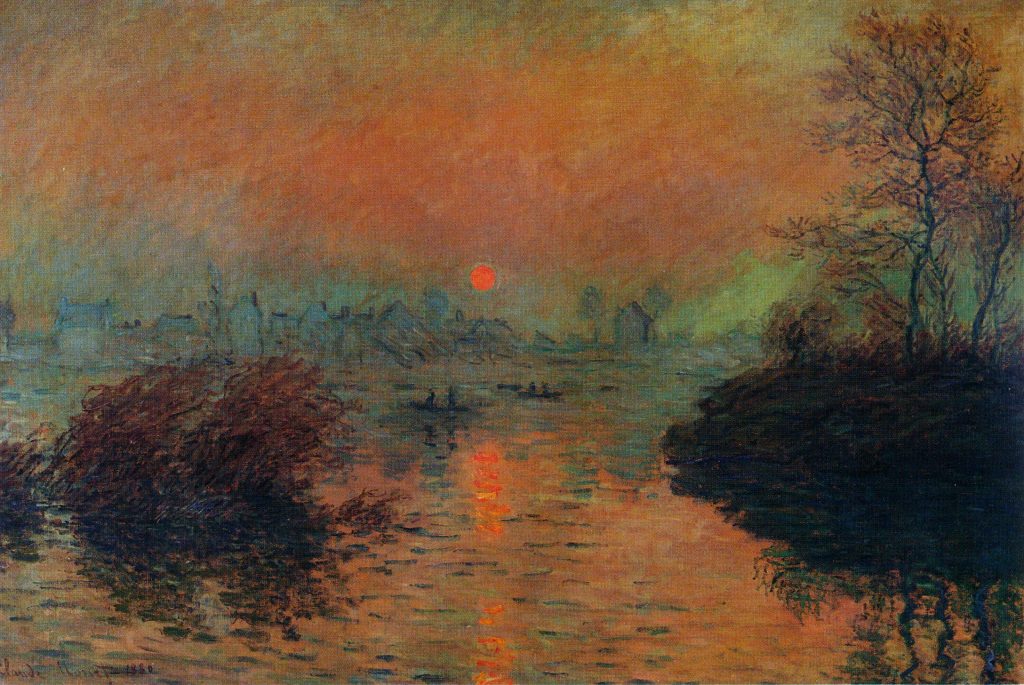

FEATURE image: P.A.-Renoir, A Luncheon at Bougival, 1881, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. The Seventh Impressionist Exhibition – 1882.

By John P. Walsh

In the five years between the “balanced and coherent” Third Impressionist Art Exhibition in April 1877 and the penultimate Seventh Impressionist Art Exhibition in March 1882 which included Gustave Caillebotte’s The Bezique Game, significant changes had occurred in the art world.

One major development that was especially impactful for the band of independent and ever-varying avant-garde artists known as the “impressionists” was that, after 1877, the group had fallen apart.

The Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877 organized by Caillebotte and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) demonstrated the benefit of a detailed marketing plan within a professional arts organization. Caillebotte’s attempted follow-up to host an impressionist exhibition in 1878, however, failed to get off the ground.

It wasn’t for any lack of his trying. In 1877, Caillebotte could measure success in the Third show by 18-count modern artists under a new brand name, along with 230 works. Show attendance numbers were up from the first and second exhibitions almost four fold. Picture sales were up.

In less than one year, the enterprise devolved to nothing tangible. This was because of a lack of collective coherence among the artists in terms of artistic and business outlook. Seeds of destruction among this klatch of mostly young, avant-garde artists became increasingly evident during the “glorious” 1877 show.

Caillebotte’s genius in the Third Exhibition was to know strengths to promote and problem to ignore. He avoided the veritable train wreck coming from associated artists who were antagonistic creatively by keeping them mostly literally physically apart.

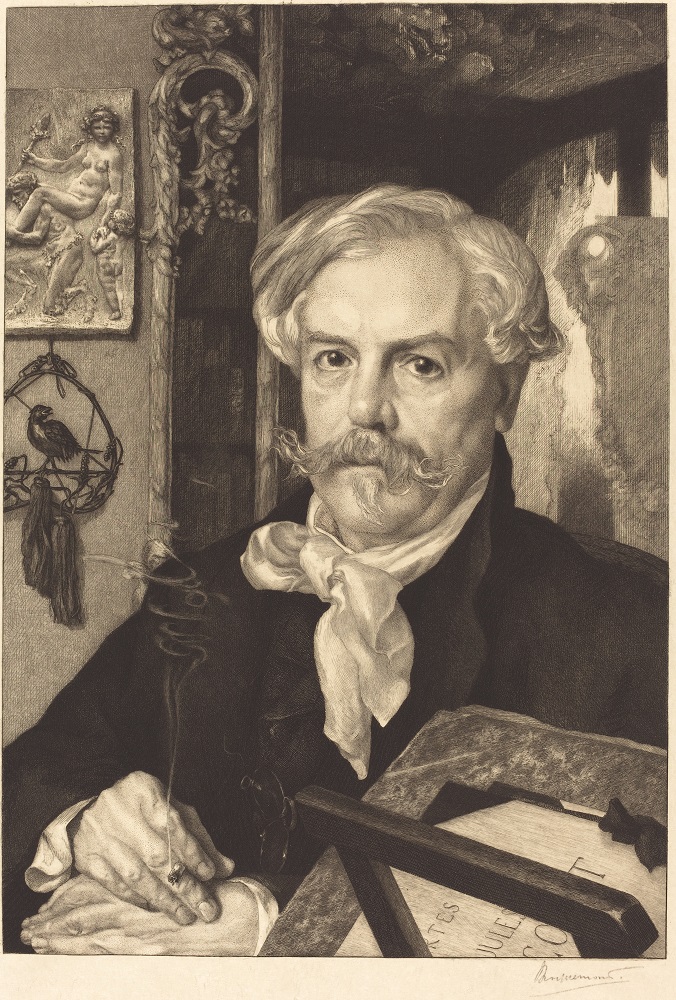

The Impressionists had two major factions. One was led by classically-trained Edgar Degas (1834-1917) with his realist urban figure drawing. The other was the nonacademic, “broken-brush” innovators or strict impressionists such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) who explored the effects of light.

For the duration of the Third Impressionist exhibition, all of Degas’s 25 beach and ballet works hung in a room of their own.

As a business seeks popular and financial success, a caveat towards that objective for the third and upcoming 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th impressionist art shows was “the terrible Monsieur Degas.”

Although Degas had an argumentative personality, major reasons for Degas’s dispute with Caillebotte’s impresionist show were not Degas’ making. After 1877, the battle line which ensued between Degas and his group of trained artists and Monet and his nonacademic group affected every next impressionist show up to the 8th and last one in 1886.

The catalyst for the Impressionists’ artistic divisions was their different understandings of what became another major development to affect the art world and all contemporary artists.

Throughout the 1860s, the Salon continued to be anti-democratic. By the late 1870s, there was a clear trend towards a more liberalized Salon. In 1881, the French government took itself out of the Salon. Even before that, in 1878, the year of the scrapped 4th Impressionist show, the government allowed strict or “broken brush” Impressionists like Monet and Renoir to participate in their “Exhibition of Living Artists.”

Whatever its drawbacks, the Salon remained the biggest art show in Paris.

While Caillebotte’s Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877 attracted 15,000 visitors in its one month run—a remarkable statistic—the Salon attracted 23,000 visitors per day.

The Salon displayed around 23x more art than the Impressionist show and attracted 50x more visitors. Opportunities for sales and new clients at one of these nineteenth-century warehouse events was immense.

In 1878, after years of fighting for greater participation in the Salon— the Salon des Refusés took place in 1863—innovative Impressionists were finally allowed to freely hang their artwork in an annual show that for hundreds of years had been the institurional enclave of the Paris art world’s elite.

Yet, In terms of the 4th impressionist art show, the bourgeois Degas devised an ingeniously small-minded idea that he presented ennobled by some principle.

Despite this historic opening of the Salon to young avant-garde artists—Monet and Renoir were in their late 30’s, Degas in his mid 40’s—the older and financially secure artist insisted that all impressionists must make a choice.

Either exhibit in the Salon or with the Impressionists.

Degas’s ultimatum was crafted to pressure the “broken brush” impressionists such as Renoir, Monet, Sisley and Cézanne to break ranks to the Salon—and likely improve their sales and reputations in a rapidly changing art market—and leave the impressionist art organization to Degas and his followers.

Degas’s wedge actually worked. By 1880, the “broken brush” impressionists were purged from the Impressionist exhibitions by their own choice to exhibit in the Salon. Though they saw no conflict with the Impressionist art organization per se that broken brush artists helped found, Degas’s ultimatum had been permitted to stand for the 4th, 5th, and 6th impressionist art shows and helped secure these Impressionist shows of 1879, 1880, and 1881 under the leadership of Degas.

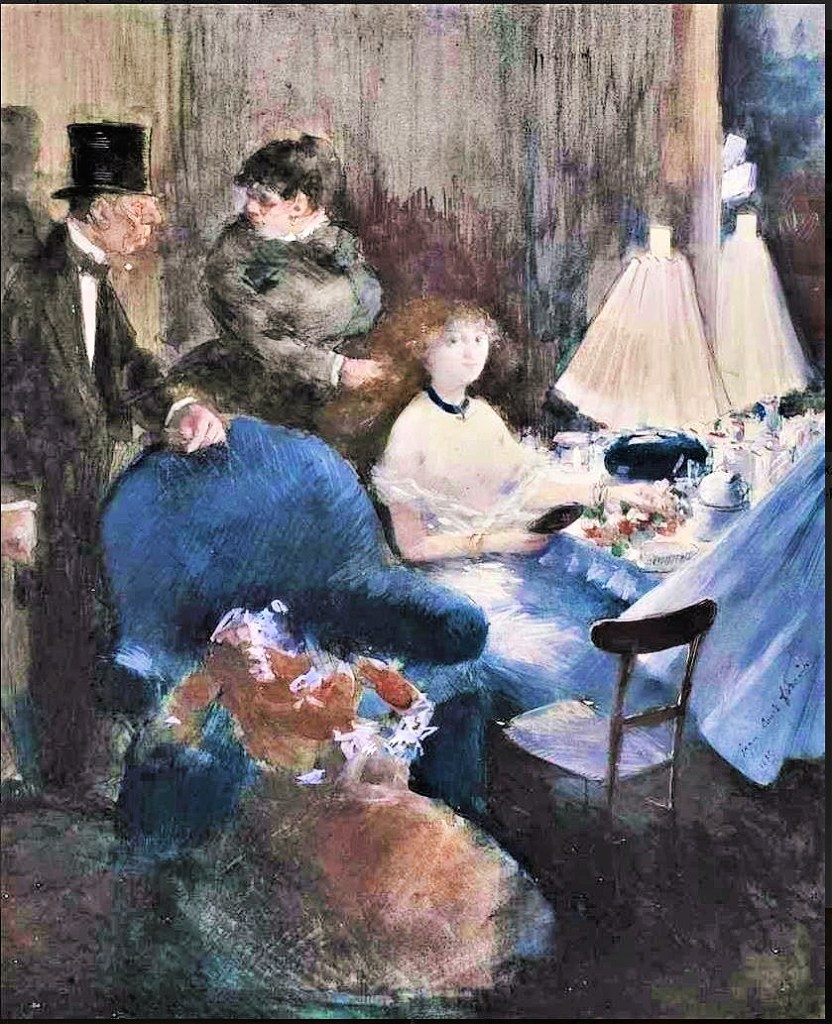

The 4th, 5th, and 6th exhibitions featured Degas and his favorite artists. It was in these Degas-led shows that the public had their first in-depth look at Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), among others.

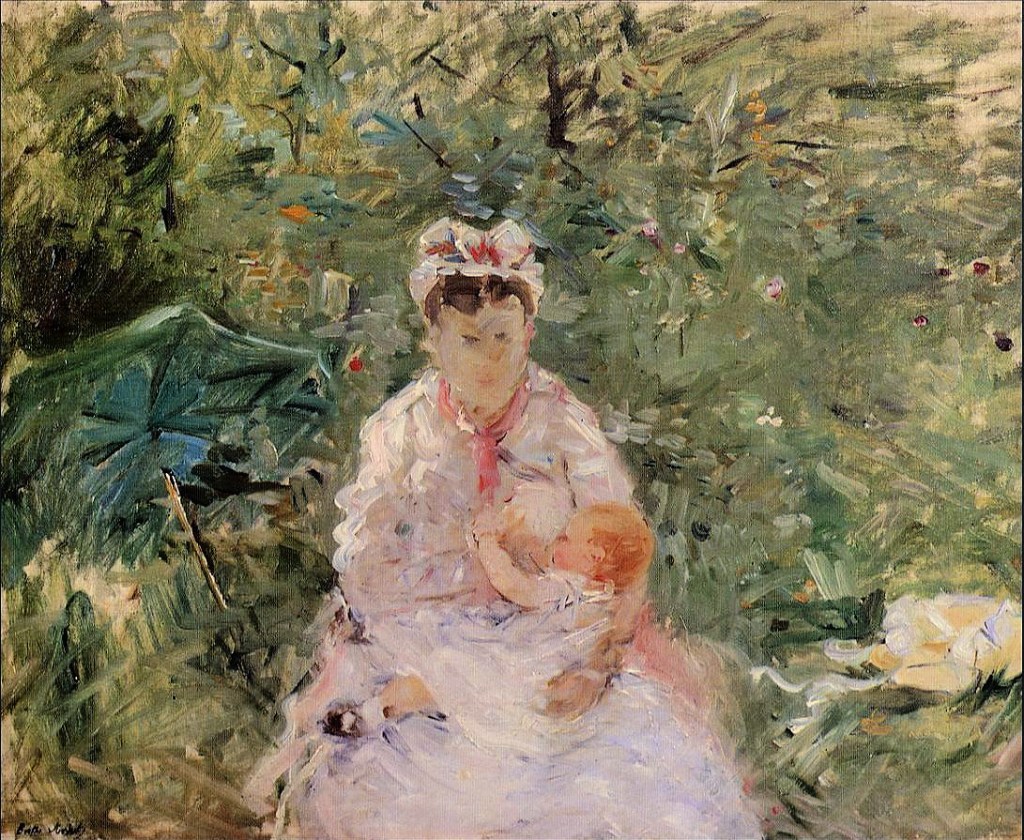

Not all of the Impressionists’ original members and strict impressionists decided to exhibit in the Salon. Camille Pissarro and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) chose to stay in the independent art group and continued doing so for the eight shows. (Morisot had a baby during the 4th and didn’t participate).

Gustave Caillebotte had invested his talent, reputation and resources into the independents since 1876 and continued to organize and exhibit with them in 1879 and 1880. Before the 6th show in 1881, Caillebotte himself finally broke with the Degas regime in a dispute nominally over a advertising issue.

As the calendar proclaimed a new decade, new opportunities for Impressionist exhibitions began percolating in Caillebotte’s head as he painted The Bezique Game (1880) within the shifting artistic environment.

The game of Bezique is a 64-card game for two players and curiously French. In the game two singles players sit across the net to compete to 1000 points. The rest are score keepers or observers. As the game carries on, card “tricks” pile up on the table.

Some art critics viewing Caillebotte’s contemporary subject of a popular game identified the painting as a “legible and tightly ordered” image out of the long-held pictorial tradition of card playing. Yet idiomatic clichés related to card playing such as “playing one’s cards right” or “holding one’s cards close to the chest” may be read into the painting. It is one of the canvasses painted by impressionist artists during this time that relate to the Impressionist group’s recent and ongoing exhibition experiences.

Nineteenth-century art critics usually grouped together the artwork of Caillebotte and Degas, Neither artist was among the “strict” impressionists such as of Monet and Renoir. Several critics wondered aloud in the newspaper why Caillebotte would even have dealings with those “broken-brush” daubers now at the Salon with Édouard Manet.

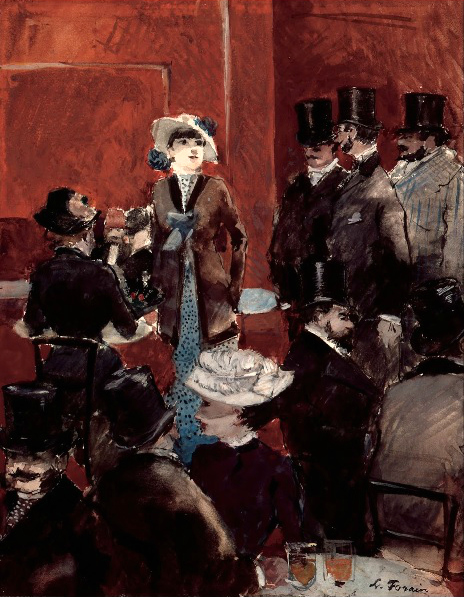

Competition between Degas’s partisans and the mostly younger strict impressionists such as Claude Monet, Renoir, and others, resulted in a schism in 1879. In addition to himself, Degas recruited talented newcomers such as Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), and Federico Zandomeneghi (1841-1917) for the 4th.

The Third Impressionist Art Exhibition held in April 1877 is known as “Caillebotte’s Exhibition.” It is the highlight of the eight Impressionist exhibitions held between 1874 and 1886. While scholars agree that the Third Impressionist Exhibition was in every sense “glorious,” the show’s euphoria was short lived. Two weeks after the show closed, as hope for picture sales grew high, there was a Constitutional crisis in the French government. The political turmoil resulted in a consolidation of Republican power defeating Royalists which led to a national economic recession. The Impressionist group, conceived and carefully built to unity by Gustave Caillebotte, resorted to squabbling as the artists jostled to survive in receding good times.

Gustave Caillebotte’s efforts for a fourth impressionist exhibition in 1878 were stymied and the next 3 exhibitions would be under Degas’s rule. In 1879 Degas exclude the “broken brish” artists Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and Alfred Sisley. In 1880, Degas cast out Claude Monet. The destructive outcome of these intramural politics was not lost on Caillebotte.

Caillebotte built the group’s brand in the Third Impressionist Art Exhibition in 1877 largely on “broken brush” impressionists nwho were excluded from Degas’s shows. Caillebotte, however, worked with Edgar Degas and his artistic coterie in 1879, 1880 and 1881. Oy was before the opening of the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in 1881 that Caillebotte finally departed the Degas-led organization. Caillebotte cited differences on an advertising issue.

Yet Caillebotte’s nonparticipation with the Impressionists was short lived.

The 32-year-old Caillebotte looked to a retro-style vision for an Impressionist Art Exhibition in 1882. His emerging partner was 51-year-old Impressionist art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922).

The Fifth exhibition lost Monet to the Salon which per Degas’s ultimatum excluded the figurehead through which the term “impressionism” received its label in 1874 from exhibiting with the group of independents in 1880. Other broken or free brush painters such as Camille Pissarro and Berthe Morisot did continue to exhibit in the 5th show. Ironically, critics responded to the truncated, Degas-led show, by wondering out loud what made this Impressionist show any different than a recently liberated Salon. While Morisot and American Mary Cassatt’s artwork received especial attention and praise in the 5th show, the month-long April 1880 show also introduced important newcomers to its Paris audience such as Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924).

Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot continued their impact as the most progressive impressionists according to critics during the 6th Impressionist show in 1881. Morisot’s Nurse and Baby was startlingly abstract to viewers of the 1881 show. Zandomeneghi’s Place d’Anvers quietly inspired artists to explore anew early Renaissance Italian mural painting. Raffaëlli, displaying over 30 works in the 6th show, made a huge impact for his realist, socially aware artwork. The 6th show’s centerpiece was Degas’ statuette of the ballet student in a fabric tutu that put impressionism in 3D and affected modern sculpture going forward. Gustave Caillebotte who had participated in the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th impressionist exhibitions (and would the 7th) as well as organized the 3rd, 4th, and 5th (and would the 7th), bowed out of participating at all in the 6th show.

The changing art market in the 1870s had taken a financial toll on the art dealer’s modern art business. Durand-Ruel re-tooled his dealership to focus not on large-scale group shows but small shows of individual artists. Overall the French economy had sunk into hard times and big shows cost more money. Following the disastrous Hôtel Drouot auction in 1875—which Durand-Ruel believed was an attempt by his critics to discredit him as an art dealer—the well-stocked Impressionist art dealer reluctantly agreed to go forward with Caillebotte’s exhibition plan for 1882. Caillebotte convinced the dealer that the Seventh show would earn a small profit.

Caillebotte’s main hook was to re-integrate the excluded “broken brush” or “strict” impressionists including Renoir and Claude Monet. Degas and his faction of artists including Mary Cassatt stayed away from the Seventh Impressionist exhibition though Paul Gauguin was represented. Also missing was the artist of Aix, Paul Cézanne, who was experimenting with volumes in the south of France. Cézanne would not be seen in a Paris art show until 1895 when a huge body of his work was featured in a landmark retrospective exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery.

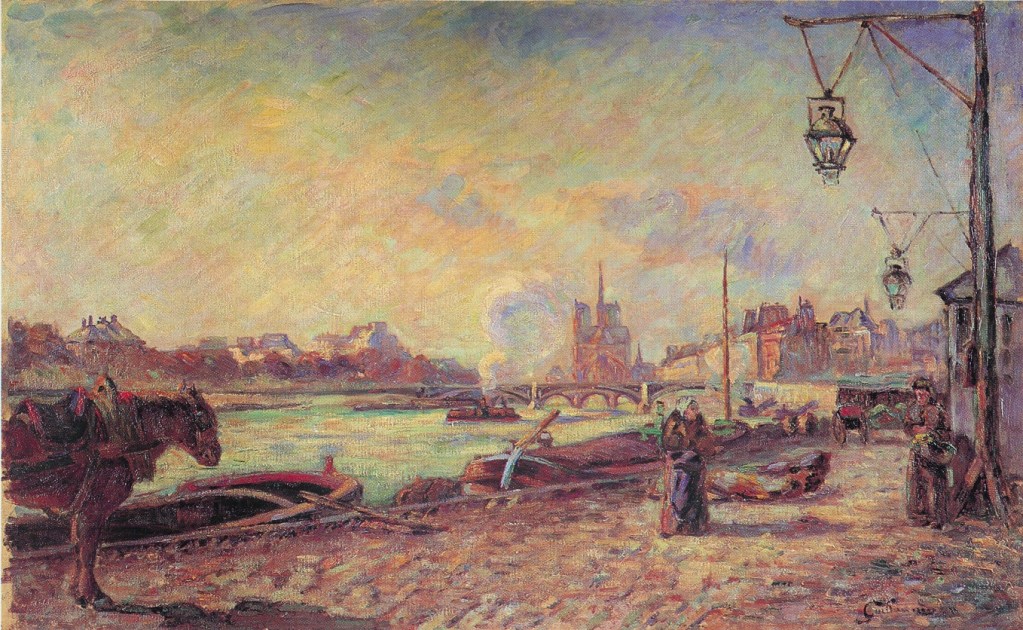

Caillebotte’s first move was to secure the popular Renoir for the upcoming March 1882 show. Renoir sent 24 new works, including his iconic large-format A Luncheon at Bougival (Un déjeuner à Bougival). Durand-Ruel insisted on a standardized presentation, including simple white frames for every work. In addition to Monet and Renoir, the seventh show hailed a triumphant return for Alfred Sisley. Camille Pissarro displayed several paintings of peasant girls. His tiny pseudo-pointillist brushstrokes overlaid with occasional dabs of thicker paint, built up an uneven surface that integrated the figure and background which worked to visually mimic the textures of the sitter’s wool clothing.

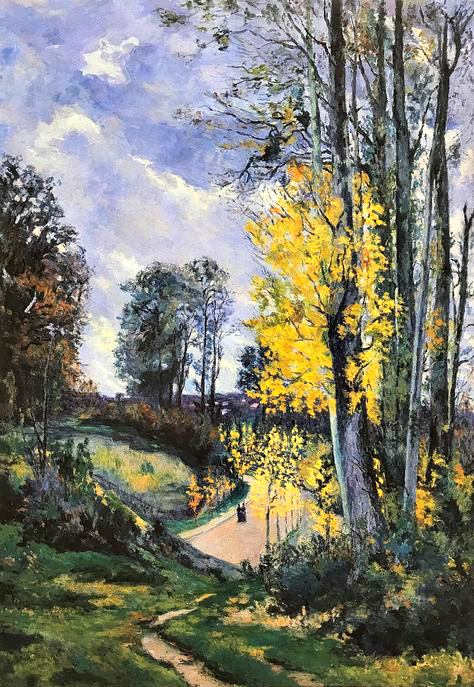

Caillebotte sent 17 works to the show. The Bezique Game (Partie de bésigue) painted in 1880, was joined by Rising Road (Chemin Montant) painted in 1881. This latter work’s path hardly rises—a feature that contributed to the canvas’s mystery. The question was asked whether it was a reprise of the “enhanced perspective” that aggravated critics in 1876 when they saw it in The Floor Scrapers.

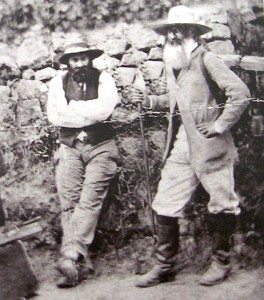

Rising Road is painted with a free handling of colors in the loose brushwork style of Monet and Renoir whose closer re-acquaintance Caillebotte made. One critic poked fun at the painting’s mysterious pair as viewers wondered with him who is “the conjugal couple…seen from the back” ? Their identities and location are uncertain although speculation has put Caillebotte in the painting with his lifelong companion Charlotte Berthier.

Rising Road (Chemin Montant) has had only two owners since 1881. It sold in 2003 for nearly $7 million ($6,727,500) at Christie’s in New York City,

Gustave Caillebotte and Impressionist art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel organized the exhibition which marked the triumphant return of the broken-brush or strict Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In many ways it was Renoir’s wide-ranging artwork that was the star of the 7th show.

Sources:

Charles Moffett, The New Painting, 1986.

Anne Distel, Urban Impressionist, 1995.

Ross King, The Judgment of Paris: The Decade that Gave Us Impressionism, 2006.

John Milner, The Studios of Paris, 1990.

Alfred Werner, Degas Pastels, 1998.

http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=4181485