FEATURED image: Napoleon near Borodino, Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904), 1897, oil on canvas, State Historical Museum, Moscow.

Major facts of the life of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) are well known. Known as Napoleon I, the French Emperor who died two centuries ago was a shrewd, ambitious and skilled military leader who conquered much of Europe in the early 19th century.

Born on the island of Corsica that had recently handed authority from Italy to France, Napoleon rose rapidly in the French military during the unsettled period of the French Revolution after 1789 and until 30-year-old Napoleon seized power in a coup d’état in 1799.

In 1804 Napoleon crowned himself emperor in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris in the presence of the pope. In the next decade Napoleon successfully waged war against various coalitions of European nations and expanded his empire. Following his disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812 explored in some detail in this post, Napoleon abdicated his throne in 1814 and was exiled to the island of Elba not far from his native Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea near Italy.

In 1815, he escaped Elba and returned to France where he briefly returned to power in his Hundred Days campaign. He received a crushing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in today’s Belgium and was exiled until his death on May 5, 1821 to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. Napoleon Bonaparte was just 51 years old at the time of his death stemming from mysterious circumstances, though likely something such as stomach cancer.1

In 2021, the bicentenary of the death of Napoleon I is commemorated. While 200 years is a long time ago, in terms of History it is a relatively short span amount of time. In other words, Napoleon, who might have come to the United States (New Orleans) after his exile, is not very far away from modern times.

Napoleon Bonaparte, born in Corsica which had just switched allegiance from Italy to France, was born in 1769. In 1821 when he died on May 5 he was 51 years old. The former French emperor died far away from Europe on the island of Saint Helena in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. Napoleon had been exiled there following his defeat at Waterloo in Belgium in 1815 and escape from Elba in the Mediterranean, the British Government’s first location for his confinement.

Between the continents of Africa and South America, St. Helena is much more remote. The island built its first airport only in 2011.

Napoleon lived on St. Helena for about 6 years and died there, somewhat unexpectedly, at Longwood House. Napoleon’s permanent residence was completed for him in December 1815.

Napoleon was buried on St. Helena. In 1840, stirring old wounds of controversy, the remains of the warring General and French despot were transferred to Paris. Napoleon’s tomb in Les Invalides had been a military hospital whose construction was by Louis XIV (1638-1715).

The death mask was made on Saint Helena about two days after the former French Emperor’s death there on May 5, 1821 at Longwood House. (see – http://www.lautresaintehelene.com/autre-sainte-helene-articles-malmaison2.html – retrieved May 5, 2021).

In 1858, French emperor Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I, purchased Longwood House and various other lands associated with Napoleon I on St. Helena for the French government. Though Napoleon’s remains were returned to France in 1840, Napoleon III’s purchase on St. Helena remains the property of France . It is administered by a French representative under the authority of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (see – https://fondationnapoleon.org/en/activities-and-services/preserving-heritage/operation-st-helena/ – retrieved May 5, 2021).

IN THE YEAR 1812 – A BAD ECONOMY, CONTINENTAL BLOCKADES, AND A DISASTROUS INVASION OF RUSSIA BY NAPOLEON

During the War of 1812 which had ramifications for the U.S., world domination by Napoleon was being attempted within a sagging, uncooperative economy in Europe.

France had 300,000 French troops and a rafter of French generals occupying Spain to keep the blockaded British from invading. Napoleon, in a near constant state of war since 1793, had created an Empire whose subjected parts didn’t cooperate. In 1812, Napoleon had to choose between losing his blockade in Spain or in Russia.

Since the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 which followed the Battle of Friedland where Napoleon defeated the Russian army, Russia continued to transact business with England. This was a violation of the agreement and the pretext for Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812.

While over 1,500 miles away from Paris, Napoleon wanted to shut down Russia’s economy and take full control. For Russia, Napoleon’s invasion required the defense of their homeland.

NAPOLEON’S NEW WAR CAMPAIGN NEEDS 700,000 CONSCRIPTED SOLDIERS

Napoleon needed fresh conscripts but a third of Napoleon’s French draftees didn’t report for duty. Many of Napoleon’s generals advised the dictator to stay in Paris and enjoy life’s spoils. Napoleon refused. He explained that he would not rest until he fulfilled the dream to form a United States of Europe.2

Napoleon assembled 700,000 men with the monumental task to pay for it. For years the Emperor had been stockpiling supplies along the route to Russia and even arranged for their delivery on the battlefield.

Napoleon left St. Cloud for Moscow in June 1812. His high stakes gamble would affect not just Napoleon’s fortunes but the Empire’s inhabitants.

Ernest Meissonier’s Campaign of France, 1814, was the artist’s first painting produced in a cycle of Napoleon’s conquests. Though the episode Meissonier depicts was painted for the fiftieth anniversary of Napoleon’s invasion of France from Elba in 1814, it captures the overall desolation that surrounded the former French Emperor by the time of his invasion of Russia in 1812.

The series made by the 49-year-old artist, an admirer of seventeenth-century Flemish and Dutch small-format painting, captures the desolate landscape the Grande Armée endured. It also depicted a solitary, unusually unkempt, and tenuous figure of Napoleon who is leading the General Staff and troops in an over-extended military campaign that spelled defeat.

For the painting, the artist’s imagination was informed by historical documentation including interviews of surviving eyewitnesses, including the detail of the Emperor’s grey coat. Its realist style was a prevailing aspect of mid-19th century artistic taste during the Second Empire headed by Napoleon III from 1852 to 1870.

FAILURE OF THE SUPPLY CHAIN

The army marched 1,200 miles to Lithuania to defeat the Russian army. But the Russians had retreated. Napoleon’s men had to march another 550 miles to Moscow. The generous supply lines got snarled. French troops turned sick and exhausted.

In the Battle of Smolensk, the French invaders—viewed by some to be fighting for a united liberal Europe over small state autocrats—set that town on fire. Napoleon’s criminal reputation preceded him – he murdered without mercy and often by treachery. Royalists criticized him but also articulate liberals like Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) and François-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848). The emperor was the enemy of liberty. Chateaubriand wrote: “Les Français vont indistinctement au pouvoir, ils n’aiment pas la liberté, l’égalité est leur idole. Or l’égalité et le despotisme ont des liaisons secrètes” (“The French go to power indiscriminately, they don’t like liberty, equality is their idol. But equality and despotism have secret links”).

With casualties for the Battle of Smolensk around 15,000 for both sides, the Czar appointed Mikhail Kutuzov (1745-1813) as commander of Russian forces. Napoleon called Kutuzov, “The sly old fox of the north“ (cited in Roger Parkinson, The Fox of the North, 1976). At 67 years old, Kutuzov was lazy and lecherous, but knew how to fight—and, regarding Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, how to retreat strategically. It made Napoleon’s thirst for further battle on his own terms impossible.

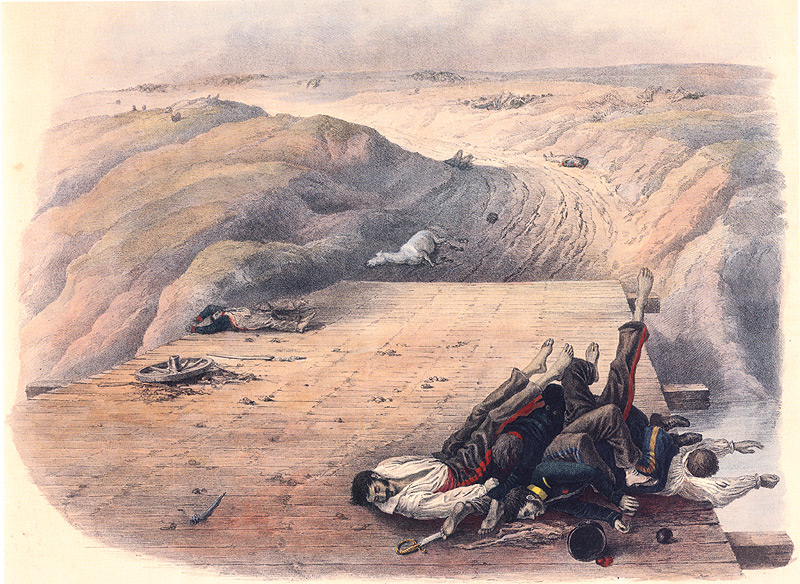

70 MILES WEST OF MOSCOW, THE BATTLE OF BORODINO PITS 242,000 TOTAL COMBATANTS WITH OVER 1,000 BIG GUNS ON SEPTEMBER 7, 1812

In his address to troops before the Battle of Borodino General Kutuzov told his men: “Napoleon is a torrent we are yet unable to stem. Moscow will be the sponge that sucks him dry.”3 Napoleon knew what he was up against. Without supplies, Napoleon ordered his men to keep marching: “Motion alone keeps this army together.”4

The march from Smolensk to Moscow took 3 weeks. Many soldiers of the Grande Armée died on the march. Kutuzov set up a defensive position in Borodino, about 70 miles west of Moscow. On Sept. 7, 1812, French forces engaged the Russians. Both sides were evenly matched – Napoleon had 587 guns and 130,000 troops and the Russians had 640 guns and 112,000 troops.

Hanging over the battlefield was the feeling that the destiny of Europe lay in the balance. The battle’s outcome was a draw. The French were masters of the field as the Russians retreated. It was another day for war’s slaughter— combined French and Russian losses was 80,000 soldiers.

In the War of 1812 Fedor Petrovich Uvarov (1769 -1824) commanded the 1st Cavalry Corps and then the Cavalry of the 1st and 2nd Russian Armies. With the Cossacks of Matvei Platov (1753-1818), Uvarov distinguished himself in the Battle of Borodino when he turned the left flank of the French army and made a raid to its rear. The Russian attack of the main French forces delayed Napoleon’s battle plans for two crucial hours.

The image of a sullen dictator (above) seated on his field chair with boots raised onto a battle drum, as his General Staff views in their spyglasses the men of the Grande Armée in harm’s way at the Battle of Borodino, can be seen as indicative of Napoleon’s exercise of arbitrary power as the first of modern history’s tyrants.

WHEN LEJEUNE’S BATTLE-PICTURES WERE SHOWN IN LONDON, EAGER CROWDS CAME TO SEE THEM FOR THEIR REALISTIC, DETAILED DEPICTIONS OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY EVENTS.

In the French invasion of Russia in 1812, Lejeune was made général de brigade and chief of staff to Davout (1770-1823). During the retreat, Lejeune was frostbitten on the face and left his post where he was subsequently arrested on Napoleon’s orders.

During his military service, Lejeune produced a series of important battle-pictures based on his experiences. They were generally executed from sketches and studies made on the battlefield. Known for their lofty perspective which, according to Chase Maenius in The Art of War[s], “offer[ed] a panoramic view of the totality of the battle’s events,” the Battle of Borodino… of 1822 is considered his masterwork.

In his Memoirs of Baron Lejeune, aide-de-camp to marshals Berthier, Davout, and Oudinot (translation, 1897), Lejeune related one of the many wretched scenes that the Napoleonic Wars produced. He wrote: “As we were pushing on the next day, we came upon two poor creatures at a turn in the road whose condition tore our hearts. They were a handsome well-built man of about forty and a woman of about thirty, also with a fine figure, both stark naked. They approached us and said to us in very good French, ‘Our home has been sacked by Cossacks, who stripped us of everything and left us as you see us. For pity’s sake help us.’ We could do nothing for them but give them a little food, and we felt very wretched as we turned away. The next day at a bivouac some distance off a fresh irresistible demand was made upon our pity, and our stock of provisions was so much reduced that I don’t know what we should have done but that some German peasants brought us a few sheep, with which we replenished our larder.” (p. 158, https://archive.org/details/memoirsbaronlej01maurgoog/page/n170/mode/2up

—retrieved May 5, 2021.)

Following the Battle of Borodino on September 7, 1812, the Russian army retreated towards Moscow and camped near Fili. A military council led by General Kutuzov assembled in a hut in Fili where, despite objections from younger generals, Kutuzov insisted on his plan to abandon Moscow.

The action not only saved the remains of the Russian army but worked to stymie and ultimately defeat Napoleon’s invasion drive. The personalities in the painting include Prince Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly (1761-1818), who was replaced by Kutuzov on order of the Czar and sits in the corner below the Virgin Mary and Child Jesus icon. Fyodor Uvarov sits near Barclay holding a paper. Nikolay Raevsky (1771-1829) sits by the window with his fingers locked together. Aleksey Petrovich Yermolov (1777-1861) stands on the far right. The much younger Yermolov resented old general Kutuzov’s plan and demanded to fight the enemy.

Napoleon and about 100,000 French troops reached Moscow on September 8, 1812, Napoleon found only Russia’s poor and displaced. Moscow was Russia’s largest city, its capital, and its Holy City—and French troops of the Enlightenment set it ablaze. The fires burned for 4 days as Napoleon’s army looted it.

Napoleon wrote a letter of apology and condolence to the Czar, Alexander I Pavlovich, the Blessed (1777-1825). One result was that Tthe Russians resolved never to surrender to their would-be conqueror. Only some of the wealthy in Russia looked to negotiate with Napoleon mainly out of fear of losing their assets, that is, the serfs. Napoleon surmised, “I beat the Russians every time—but that does not get me anywhere.”5 Old general Kutuzov’s inaction attained his objective to defend Russia whereas 43-year-old Napoleon failed to rally his men for his Empire these many hundreds of miles from home.

Napoleon’s interest became retreat. There was an intended coup d’état in Paris that Napoleon had to raise more fresh recruits to crush. Other parts of the Empire also raised their head following Napoleon’s inglorious retreat. But it grew worse to become one of world history’s worst defeats.

Weather in Russia turned to snow and ice. The Russians retreated into Mother Russia before they were defeated. The French retreated to the west in defeat. Reports of cannibalism among Napoleon’s army is recorded. Turning back to Paris, the French army lost another half of their men. All of Napoleon’s supply lines had been sacked. Adding further injury, the French were chased out of Russia by Kutuzov’s 80,000 troops.

On the retreat, surviving warriors fought among themselves over any existing supplies. Napoleon’s retreat included the humiliation of being chased out of Russia by Kutuzov’s redeployed 80,000 troops. The old man’s hot pursuit did not allow Napoleon, the once young Enlightenment military figure, to rest.

Under military surgeon Baron Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842), the Grand Army’s medical and sanitary measures were the finest in the world but the retreat route offered no food and no medical care. As a remedy for possible future ills, including his capture, Napoleon convinced his doctor to give him a vial of poison which the dictator could ingest if conditions deteriorated to become inescapably dire.

Baron Dominique Jean Larrey was a French surgeon and military doctor who distinguished himself during the near endless wars of the French Revolution and under Napoleon. Baron Larrey served as the Grand Army’s medical and sanitation leader and was an important innovator in triage who is considered the first modern military doctor and surgeon.

During the Russian Campaign, Fournier commanded a brigade of light cavalry composed of French, German, and Central European horsemen, and led a noted cavalry charge at the Battle of Smolensk.

Generals Kutuzov and Wittgenstein attacked at a bridge crossing in what today is Belarus. Hundreds of Frenchmen drowned. To slow the attack, Napoleon ordered the bridges destroyed. In the process the general stranded hundreds of his troops to enemy gunfire.

Napoleon now told his aide-de-camp, Armand-Augustin-Louis de Caulaincourt, what the Russian campaign taught him: “I can hold my grip on Europe only from the Tuileries.” In Warsaw, Napoleon met Abbé de Pradt, his ambassador, and told him: “From the sublime to the ridiculous is but a step.”6

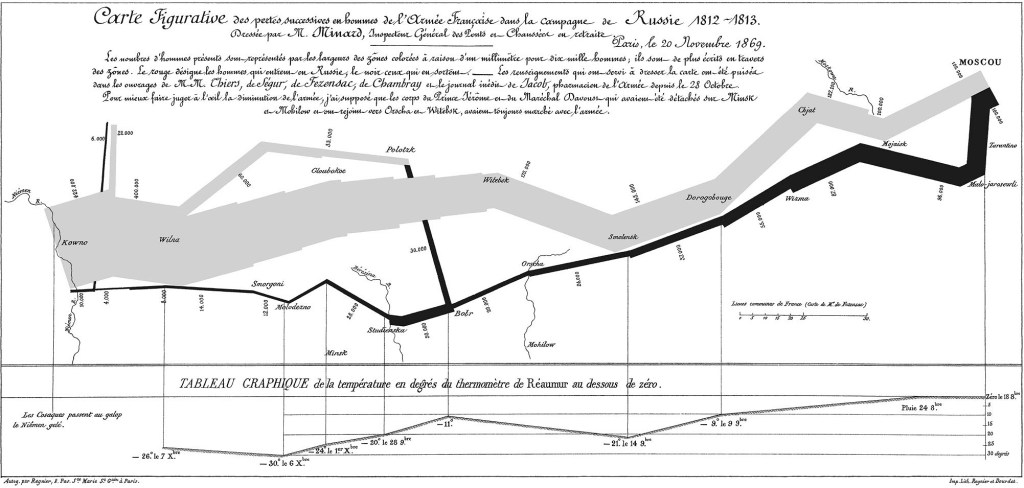

As Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture with its famous climax using cannon fire, ringing chimes and brass fanfare, commemorates a Russian defensive victory, French losses were staggering. Of Napoleon’s 700,000 men led into Russia, only 30,000 survived. Only 1,000 soldiers returned to active duty.7

NAPOLEON IN RUSSIA, HIS FORCES LOSE THE PENINSULAR WAR IN SPAIN; THE FOLLOWING YEAR, IN 1813, NAPOLEON LOSES THE BATTLE OF LIEPZIG, THE LARGEST LAND BATTLE UNTIL WORLD WAR I.

Simultaneous with the debacle of Napoleon’s Russian invasion, French forces lost the long fight (since 1808) in Spain and Portugal to keep the British off the Continent.

Significant losses in the east and west of the Empire were followed in 1813 by the Battle of Leipzig, Napoleon’s penultimate defeat by an international coalition that included Austria, Prussia, Russia and Sweden.

NAPOLEON FORCED TO ABDICATE IN 1814. EXILED TO ELBA; DEFEATED IN 1815 AT WATERLOO.

After Napoleon withdrew into France, in March 1814 these allied forces captured Paris. By early April 1814 Napoleon was forced to abdicate as Emperor. Napoleon had to go for his pursuit of glory had become a menace to his country and the world.

With the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Napoleon was exiled to Elba, and, following his brief escape into France in 1814, he was defeated for the final time at the Battle of Waterloo and exiled to St. Helena which held him until his death at 51 years old on May 5, 1821.

NOTES:

1. see- https://www.history.com/topics/france/napoleon

–retrieved May 5, 2021.

2. The Age of Napoleon, Will and Ariel Durant, Simon & Schuster: 1975, p. 698.

3. A Dictionary of Military Quotations, edited by Trevor Royle, Routledge: 1989, Section 105, quote 13.

4. http://www.military-info.com/freebies/maximsn.htm

5. The New York Times, “The Napoleon Legend—A New Look; How can we know the man whose transformation into a myth began long before his death?; Napoleonic Legend,” April 5, 1964. https://www.nytimes.com/1964/04/05/archives/the-napoleon-legenda-new-look-how-can-we-know-the-man-whose.html#:~:text=When%20he%20failed%2C%20he%20never,in%20defense%20of%20their%20country.–retrieved May 5, 2021.

6. Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 13th edition, p. 199.

— retrieved May 5, 2021.