FEATURE image: Cú Chulainn dying in battle, 1911, bronze, by Oliver Sheppard (1865 – 1941), General Post Office (G.P.O.), Dublin, Ireland. Public Domain.

By John P. Walsh. May 12, 2016.

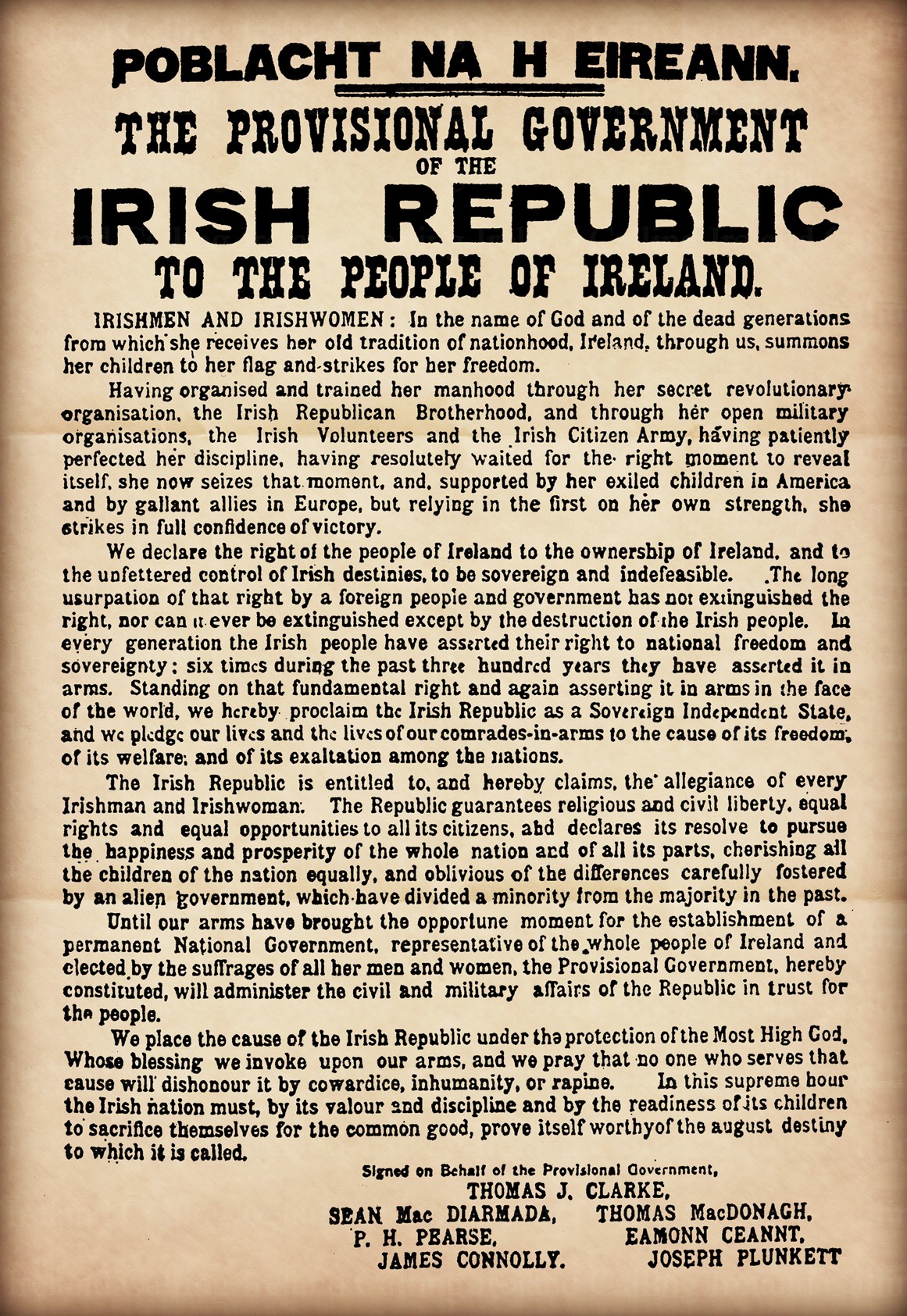

Today marks the centenary of the final executions of Irish rebel leaders by British firing squads in connection with the 1916 Easter Rising which proclaimed an Irish Republic and left Dublin in ruins. James Connolly and Seán Mac Diarmada—the final two of 14 executions that began on May 3, 1916 with the executions of Pádraic Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and Thomas Clarke—died in the same fashion as the others: taken at dawn from their cells into a Kilmainham Jail yard—Connolly tied to a chair because his battle wounds in the Rising made him too weak to stand—and summarily shot dead. Three years later, in April 1919, military forces under British command halfway around the world in India reacted with similar cruel and vindictive logic to national protest—this time one that was nonviolent—which by official British statistics killed 379 and wounded 1200 Indians in what is known as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

EXECUTED ON MAY 3, 1916:

PÁDRAIC PEARSE (1879-1916), school headmaster, orator, and writer. The extended court-martials and executions by British General Maxwell of Irish rebel leaders—as well as arrests of hundreds without trial following the general surrender on April 29, 1916—fulfilled Pearse’s romantic and revolutionary ideology expressed in notions of “blood sacrifice.” Pearse’s idea was that Ireland “was owed all fidelity and always asked for service (from its people), and sometimes asked, not for something ordinary, but for a supreme service.” Pearse was one of seven signatories of the Irish Proclamation.

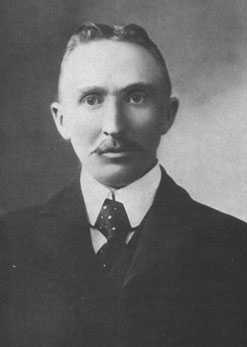

THOMAS MACDONAGH (1878-1916). Poet, playwright, educationalist. A leader of the Easter Rising – MacDonagh was one of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. He wrote letters to loved ones in jail before being executed expressing the hope that his death would share in the custom of blood sacrifice for Irish freedom. MacDonagh wrote that he was proud to “die for Ireland, the glorious Fatherland” and anticipated that his blood would “bedew the sacred soil of Ireland.”

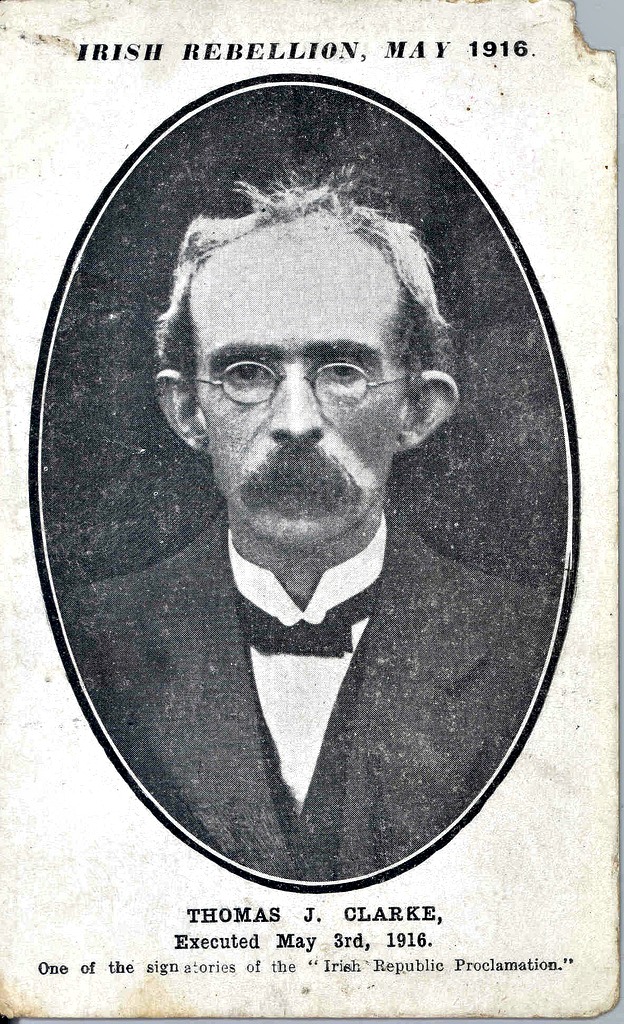

THOMAS J. “TOM” CLARKE (1858-1916). Deeply involved with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) since youth, Clarke established in 1915 the Military Committee of the IRB to plan what became the Easter Rising. A signatory of the Irish Proclamation, Clarke was the oldest rebel to be shot by the British in May 1916. Sergeant Major Samuel Lomas who helped shoot the three Irishmen on May 3, wrote that unlike Pearse and MacDonagh who died instantly, “the…old man, was not quite so fortunate requiring a bullet from the officer to complete the ghastly business (it was sad to think that these three brave men who met their death so bravely should be fighting for a cause which proved so useless and had been the means of so much bloodshed).”

The rising involved a treasonable conspiracy that resulted in the deaths of British soldiers among the 418 people killed in and around Dublin. The penalty for such action would certainly call for capital punishment in Western European countries in 1916. It is surprising that executions were kept to under 15 rebels, although British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith (1852-1928), following the first three executions on May 3, 1916, expressed concern that the trials and death sentences were being briskly implemented. General Maxwell’s blunder was to stretch out the executions over two weeks, where the element of daily shock and surprise as to who made the list of the dead forever changed the tide of Irish public opinion against British rule.

General Sir John Maxwell (1859-1929) was the military governor in Ireland. He ignored all appeals by British politicians — including the Prime Minister and Roman Catholic bishops in the United Kingdom — to halt the executions.

EXECUTED ON MAY 4, 1916:

JOSEPH PLUNKETT (1887-1916). Hours before he was executed on May 4, 1916, sickly Joseph Plunkett married his fiancée Grace Gifford in the prison chapel. Thomas MacDonagh, who was executed on May 3, had married Grace’s sister Muriel Gifford in 1912. Plunkett, who came from a wealthy background, was a poet and journalist, a member of the Gaelic League, and a standing member of the IRB Military Committee that planned the Easter Rising. During the Rising, Plunkett’s aide de camp was Michael Collins. Plunkett signed the Irish Proclamation.

EDWARD “NED” DALY (1891-1916). From Limerick, Ned Daly was commandant of the 4th Battalion, where some of the fiercest fighting of the Rising took place. Daly’s father had taken part in the Fenian Rising of 1867; his uncle, John Daly, served 12 years in English jails; and his sister, Kathleen, was married to Thomas Clarke. Daly commanded the Four Courts garrison during Easter Week 1916. Though there were not enough Volunteers to hold all posts, following the bitter battle of Mount Street Bridge, Daly and his comrades still held the Four Courts, and other significant outposts in Dublin until called by Pearse to a general surrender.

WILLIAM “WILLIE” PEARSE (1881–1916) was the younger brother of Padraic Pearse. Willie stayed by his brother’s side during the entire Rising at the General Post Office (G.P.O.) which served as rebel headquarters. In Kilmainham Jail Willie was promised he could visit his brother before he died on May 3, but the British hid the truth of it since Padraic Pearse was shot as Willie was being taken to see him.

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN (1877-1916). Michael O’Hanrahan had come to a newly-formed Sinn Féin out of his work with the Gaelic League as a linguist and published writer where he founded its Carlow Branch and later worked with Maude Gonne and Arthur Griffith. Like Edward Daly, his father had been deeply involved in the Fenian Rising in 1867. O’Hanrahan was the National Quartermaster for the Irish Volunteers and, during the Easter Rising, served under Thomas MacDonagh of the 2nd battalion based at Jacobs Factory.

EXECUTED ON MAY 5, 1916:

MAJOR JOHN MACBRIDE (1868-1916). Second in command at Jacob’s Biscuit Factory during the Easter Rising. MacBride had had a colorful career previously as an Irish émigré to South Africa where in 1899 when the Second Boer War broke out he raised a brigade of other Irish emigrants who fought bravely against the British. Upon his return to Ireland he married (and divorced) Maude Gonne. Now facing the British firing squad in May 1916 at Kilmainham Jail, MacBride refused a blind fold. He told his executioners, “I have looked down the muzzles of too many guns in the South African war to fear death and now please carry out your sentence,” which they did.

Irish public opinion changed virtually overnight regarding the rebels who had brought the central city of Dublin down onto their heads during the 1916 Easter Rising. At the surrender Volunteers were jeered and cursed on their way into British hands. Two weeks and 14 executions later, they were forever-after hailed as Irish heroes. The attitude of the Irish populace to their British overlords during martial law turned spiteful. The British lost their credibility as a civilizing force for the island. The executed Irish rebel leaders were not saints although some such as forty-one-year-old Michael Mallin, thirty-four-year-old Éamonn Ceannt and twenty-seven-year-old Con Colbert were devoutly religious Catholics. They offered a modern dream of an independent Irish Republic and did it at the supreme sacrifice of their lives. These rebels’ fixity in the pantheon of Irish history rests in large measure on imagery and legend for their undeniably courageous but failed six-day insurrection. Self-appointed, this group of mostly young idealists who by force of arms, will, and words were able, despite a dastardly outcome, to have had an enduring impact on an independent Ireland is well worth remembering today.

EXECUTED ON MAY 8, 1916:

ÉAMONN CEANNT (1881-1916). Inspired by nationalist events such as the Second Boer War, Éamonn Ceannt joined the Gaelic League which promoted Irish culture. There he met Padraic Pearse and his future wife, Aine O’Brennan. A talented musician and Irish linguist, he joined Sinn Féin and the IRB which was sworn to achieve Irish independence. With Joseph Plunkett and Sean Mac Diarmada, Éamonn Ceannt served on the IRB Military Committee which planned the Easter Rising. He signed the Irish Proclamation. During the Rising, Ceannt saw intense fighting as commandant of the 4th Battalion of the Volunteers stationed south of Kilmainham Jail where he would later be executed. In prison he wrote: “I die a noble death, for Ireland’s freedom.”

MICHAEL MALLIN (1874–1916). With Constance Markievicz as his deputy, Michael Mallin commanded the Irish Citizen Army under James Connolly at St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin during the Rising. At his court martial Michael Mallin, the father of five children, claimed he was not a Rising leader nor had a commission in the Irish Citizen Army. Since the British refused to execute Countess Markievicz, Mallin became their best alternative although his garrison had inflicted little damage from the Green. Mallin had had a fourteen year career in the British Army where, while stationed in India, he became anti-British. In Ireland he rose to become a leading official in the silk weavers’ union where he successfully negotiated a 13-week strike lockout. His negotiating skills led to an appointment as deputy commander and chief training officer of the Irish Citizen Army which was formed by James Connolly to protect workers from employer-funded gangs of strike-breakers. In 2015, Mallin’s youngest child, who became a Jesuit priest, celebrated his 102nd birthday.

SÉAN HEUSTON (1891-1916). A railway clerk, Séan was a member of Fianna Éireann, a youth organization which helped raise soldiers for the Irish Volunteers and had outreach to the IRB. During the 1916 Easter Rising, he held the Mendicity Institution on the River Liffey with only 26 Volunteers when after more than two days, “dog-tired, without food, trapped, hopelessly outnumbered, [they] had reached the limit of [their] endurance” and surrendered. Heuston Train Station in Dublin is named for this Irish rebel who had worked there in a traffic manager’s office.

“Con” Colbert (1888-1916). Like Séan Heuston, Colbert joined Fianna Éireann – an Irish nationalist youth organization founded by Bulmer Hobson and Constance Markievicz – at its first meeting in 1909. The night before Con Colbert was shot on May 8 – he had been a student of Pádraic Pearse at St. Enda’s School – he asked to see a Mrs. Séamus Ó Murchadha who was a prisoner since she cooked meals for the Irish Volunteers during the Rising, including Colbert. The 27-year-old rebel told Mrs. Ó Murchadha he would be “passing away” tomorrow at dawn and that he was “one of the lucky ones” to die for Ireland’s freedom. Colbert told her he was going to leave his prayer book to one of his twelve siblings and gave Mrs. Ó Murchadha three buttons from his Volunteers uniform. He asked her that when she heard the shots at first light that would kill him, Éamonn Ceannt, Sean Heuston, and Michael Mallin to say a “Hail Mary” for each of their departed souls. Colbert also requested that the other women prisoners, reprimanded that morning for saluting the men going to the jail’s Sunday Mass, to do the same. According to the surviving Mrs. Ó Murchadha, the British soldier guarding Colbert began to cry as he heard their exchange and said: “If only we could die such deaths.”

May 12, 1916 now arrived. Twelve rebel leaders had been shot since May 3 and there would be two more today. In that short amount of time the traitors of Easter week became Ireland’s martyrs and ascendant heroes. Their pictures started to be hung in Irish homes and their poetry read for inspiration. W.B. Yeats wrote his famous verse about Ireland shortly after the Rising and its executions: “a terrible beauty is born.” A mythical Cú Chulainn dying in battle, an image beloved by Pádraic Pearse, had suddenly become real.

EXECUTED ON MAY 12, 1916:

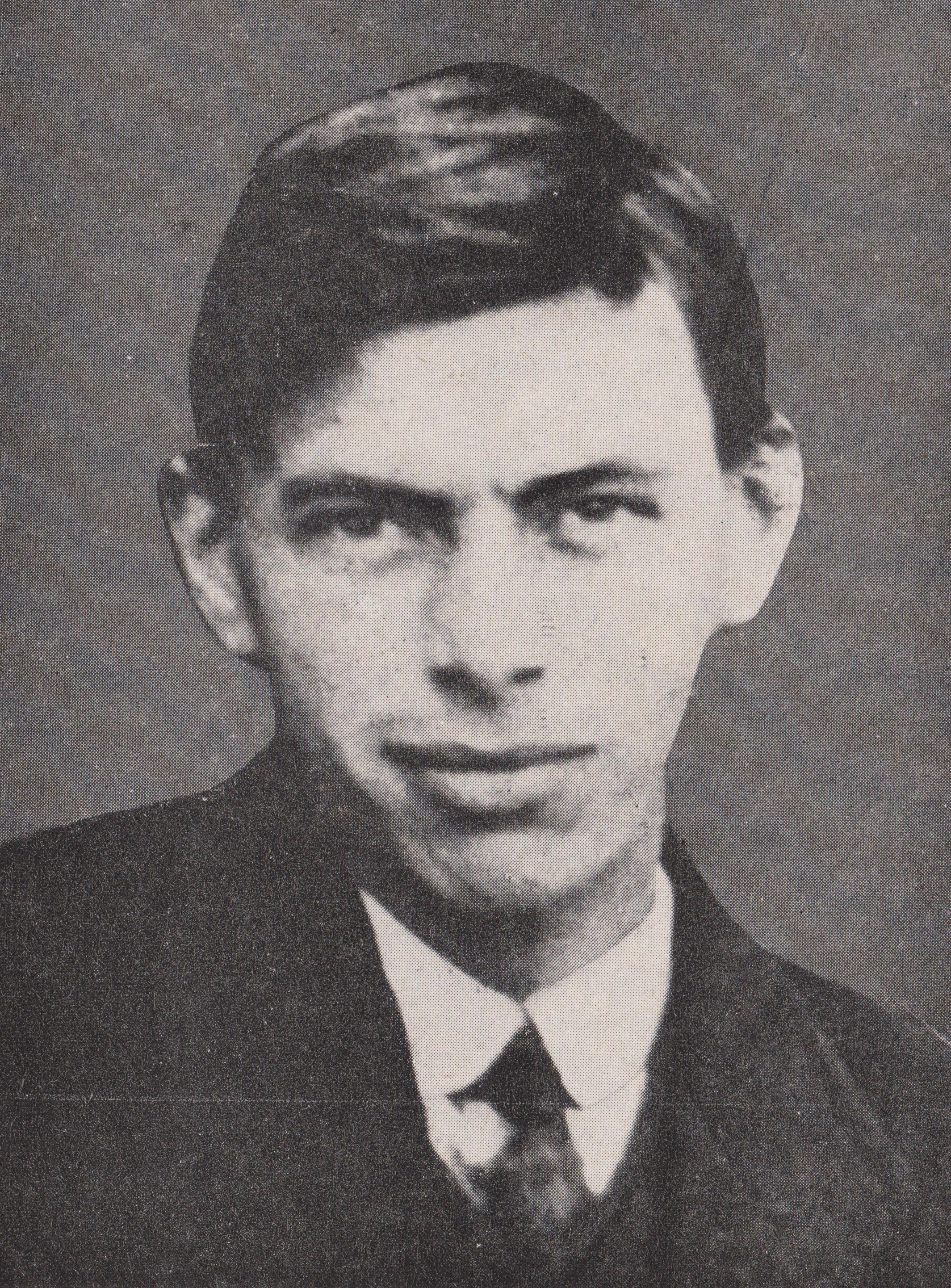

SÉAN MAC DIARMADA (1883-1916). Séan Mac Diarmada was on the IRB Military Committee which planned the Rising and a signer of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Mac Diarmada promoted Irish nationalism in the Gaelic League and in the Irish Catholic fraternity of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. He organized for Sinn Féin, managed Irish Freedom, a radical newspaper started in 1910 by Bulmer Hobson, and helped found the Irish Volunteers. After the surrender, Mac Diarmada, who had been with Pearse at the G.P.O., nearly escaped but was identified by Daniel Hoey of G Division who, in 1919, was shot himself by a firing squad with Michael Collins standing behind it. The British Officer Lee-Wilson who ordered Mac Diarmada to be shot rather than imprisoned, was also murdered on Collins’s order during the Irish War of Independence. Before his execution, Mac Diarmada wrote: “I feel happiness the like of which I have never experienced. I die that the Irish nation might live!”

JAMES CONNOLLY (1868-1916). James Connolly stood aloof from the Irish Volunteers because he considered the leadership to be too bourgeois and not concerned enough with the plight of Ireland’s workers. Roman Catholic by birth and committed socialist by choice, Connolly considered using his Irish Citizen Army to strike a blow for Irish independence in early 1916 (Michael Collins later announced that he “would have followed [Connolly] through hell”). The IRB’s Tom Clarke and Padraic Pearse fostered a partnership between the Irish Volunteers and Connolly’s ICA for the Easter Rising in 1916. Connolly became the de facto Dublin commander at the G.P.O. After his capture, because he was severely wounded, Connolly was held in a makeshift infirmary at Dublin Castle instead of at Kilmainham Jail. He might have died just from his wounds, but the execution order was given out and on May 12, 1916 the last prisoner was shot. To his executioners Connolly reportedly said: “I will say a prayer for all men who do their duty according to their lights.”

On May 12, 1916 at Kilmainham Jail in Dublin, James Connolly is brought to his execution by British soldiers. Connolly was shot by a firing squad after being carried in on a stretcher from a first-aid station at Dublin Castle.

NOTES –

“died in the same fashion” – see Britain & Irish Separatism: from the Fenians to the Free State 1867/1922, Thomas E. Hachey, The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, D.C., 1984, p. 176.

For the Jallianwala Bagh massacre see – Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (Monograph series / Indian Council of Historical Research), V.N. Datta and S. Settar, Pragati Publications, 2002; Imperial Crime and Punishment: The Massacre at Jallianwala Bagh and British Judgment, 1919-1920, Helen Fein, University of Hawaii Press, 1977; Jallianwala Bagh Massacre; A Premeditated Plan, Raja Ram, Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, 2002; The Historiography of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, 1919,Savita Narain, Spantech & Lancer, 1998.

Pearse’s idea of blood sacrifice – quoted in Dividing Ireland: World War I and Partition, Thomas Hennessy, Routledge, London, 1998, p.126.

MacDonagh letter excerpts – quoted in Last Words: Letters and Statements of the Leaders Executed after the Rising at Easter 1916, edited by Piaras F. MacLochiliann, The Stationary Office, Dublin, 1990, pp.55-56.

Sergeant Major Samuel Lomas on Tom Clarke – quoted at http://www.irishmirror.ie/news/irish-news/enemy-files-rte-documentary-gives-7591758.

418 people killed – Myths and Memories of the Easter Rising: Cultural and Political Nationalism in Ireland, Jonathan Githens-Mazer, Irish Academic Press, Portland, OR, 2006, p.120.

P.M. Asquith expressed surprise – http://www.irishmirror.ie/news/irish-news/enemy-files-rte-documentary-gives-7591758.

On Edward Daly – http://www.anphoblacht.com/contents/24778.

On Michael O’Hanrahan – http://www.nli.ie/1916/exhibition/en/content/risingsites/jacobs/ and http://thewildgeese.irish/profiles/blogs/no10-in-the-series-s-on-the-leaders-of-the-19116-easter-rising.

Éamonn Ceannt quote – MacLochiliann, pp. 141 and 171.

Collins quote – Michael Collins: The Man Who Made Ireland, Tim Pat Coogan, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002.

Connolly quote – For the Cause of Liberty: A Thousand Years of Ireland’s Heroes, Terry Golway, Simon and Schuster, 2012.