FEATURE image: Staff members of The Charles A. Stonehill Estate on the beach, c. 1912.

By John P. Walsh

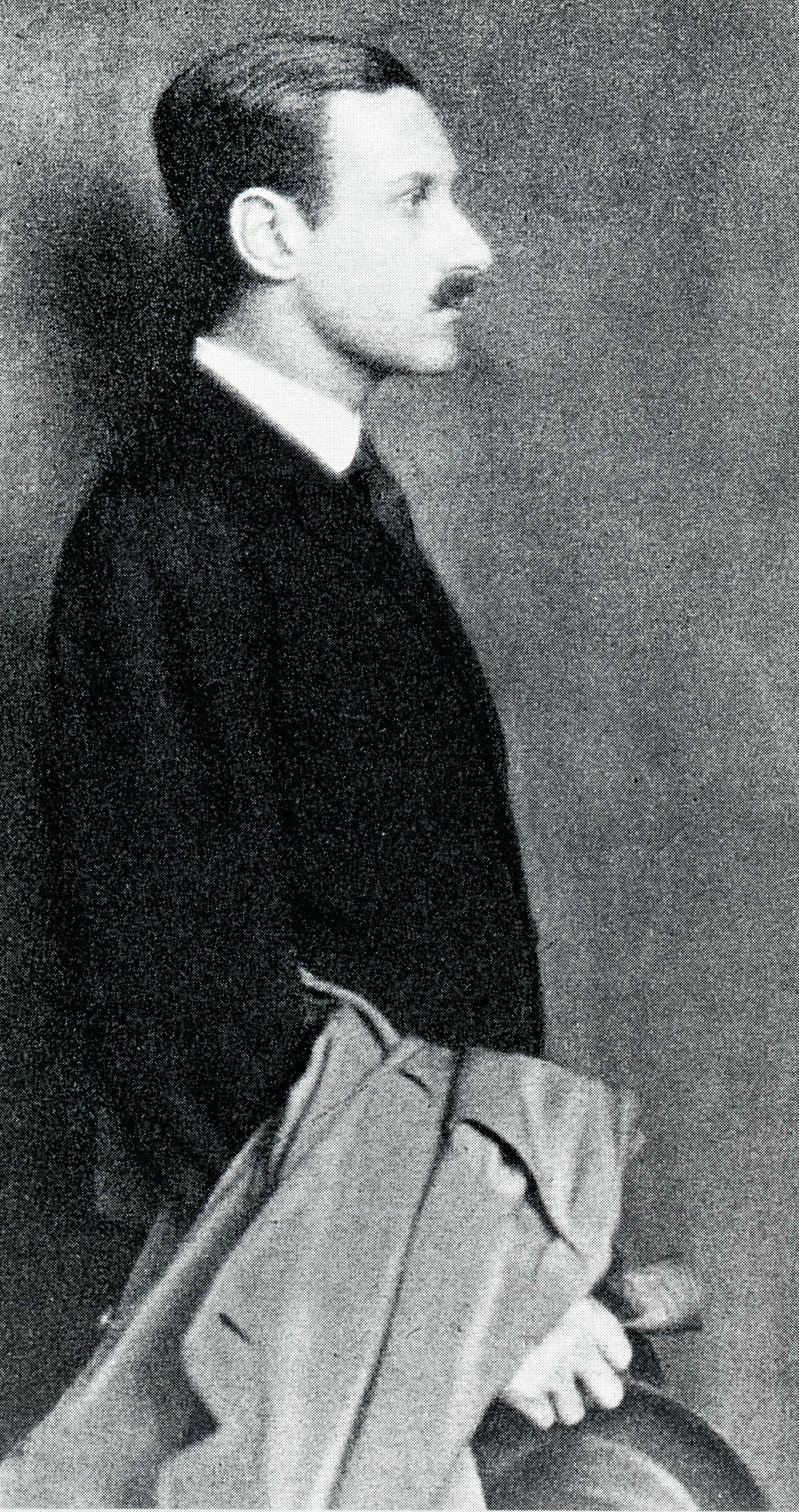

David Adler (January 3, 1882 – September 27, 1949) was an American architect who made major contributions in domestic architecture for mostly affluent clients in and around Chicago. Different than German-American modernist architect Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) who also practiced in Chicago around the same time, David Adler’s important work drew from the past for his architectural idioms.1 What are these artistic arrows in Adler’s quiver and what makes his work interesting and valuable today?

Buildings intact and standing today.

A great amount of his domestic buildings are still standing and mainly intact for the viewer to see and experience today. Only seven of his architectural projects have been demolished. These monuments of a gilded age attract one’s attention by their powerful presence based on their typical enormity, ornate details, and tasteful grace rooted in the classic European style. Gigantic skylights, curved staircases, ornate fanlight windows, columns, working fountains, and many other features, characterize Adler’s homes for his clients.

Based on his commissioned projects, David’s Adler’s architectural career spanned from 1911 following his return from studying in Europe after an undergraduate career at Princeton University, until the year of his death in 1949.

Early work and later updates.

In 1913, 31-year-old Adler was designing and building outside of the Chicago area—specifically, a chapel and iron gates at Greenwood Cemetery in Galena, Illinois.

After 1915, he was doing out-of-state projects such as the Berney house and garage in Fort Worth, Texas and the Dillingham house in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Adler’s grandiose floor plans made their appearance at the start of his career in 1911 and continued over 38 years in more than 200 major works, several of which he returned to in later years and updated.

Diverse projects for social elite.

His work includes mostly houses, whether complete or in alterations and additions, but also apartments, townhouses, gates and terraces, outbuildings and dependencies, clubhouses, locker rooms, bathhouses, swimming pools, cottages, commercial buildings, boardrooms, lodges, prefabricated houses, houseboats, and in 1924, a dining car for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad. In the late 1940s, Adler turned to designing an altar and headstones for the social elite.2

Adler planned and built in locations throughout the United States including the aforesaid Fort Worth, Texas and Honolulu, Hawaii; Wisconsin; Minnesota; Massachusetts; New York City and State; Connecticut; Colorado; Georgia; California; Florida; Louisiana; Virginia; New Mexico; as well as internationally, including British Columbia; and London, England.

Work in and near Chicago, Illinois.

The vast majority of his commissions—whether he planned and built them or only planned them—are found in the American Midwest, especially in Illinois, and particularly in and around Chicago.

While some Adler commissions were also planned but not constructed, only a handful of buildings have been so far razed. This translates for today’s viewer into a near complete body of Adler’s architectural work to be appreciated (although most remain in private hands).

Anti-Modernist, European tradition and American taste.

As streamlined, monumental and functional modernist architecture made its appearance in the late nineteenth century based in part on the stylistic language of industrialization, the wealth generated in that prosperous machine age became concentrated in the hands of individuals and their families who, having begun the perennial pilgrimage of American tourists to Europe, desired to live in private residences that evoked the palatial surroundings of historical nobility.3

David Adler’s “traditionalist” work in the first half of the twentieth century was part of, and built on, the great American tradition of architects who relied on European antecedents but adapted them to contemporary American taste. Additionally, Adler’s years in Europe between 1908 and 1911, especially in France, and his return to Chicago which like other cities in the United States after 1890 experienced a Beaux-Arts (academic neoclassical) renaissance, led him to embrace traditional architectural systems and rules for his clients throughout his career.

Honorary licensed architect of the “Great House.”

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s Adler’s architectural practice— surprisingly he was not a licensed architect although he received an honorary license in his mid-career—encountered socioeconomic conditions in Chicago and elsewhere that benefited his early and later design success.

Proliferation of his traditional work is more remarkable when viewed in the context of the modernist architectural achievements which were materializing on the landscape in the United States and Europe in those same years he practiced.4

Onset of the Great Depression and Memorial Service at The Art Institute of Chicago.

By the end of his life Adler expressed regret that the lengthy era of the “great house” was over. In the Great Depression in the 1930s, Adler had to adapt to designing smaller-scaled projects.

When Adler died unexpectedly at 67 years old in 1949, he left new commissions on the drafting table. His memorial service was held in The Art Institute of Chicago where Adler had been a board member for almost twenty five years and he was buried in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery.

NOTES

- The Country Houses of David Adler, Stephan M. Salny, Introduction by Franz Schulze, W.W. Norton & Company, New York and London, 2001. p. 9.

- Ibid., pp.193- 203.

- Ibid., p. 10; see We’ll Always Have Paris, American Tourists in France since 1930, Harvey Levenstein, The University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Country houses, p.11.

Charter Club, Princeton, New Jersey, 1903. Razed in 1913.

Adler’s sketch in 1905 for Princeton’s Charter Club.

The Charter Club based on Adler’s design. One of Princeton’s undergraduate eating clubs.

Charter Club, symmetrical Georgian Revival design. The entrance portico was supported by four Doric columns that partly masked a balcony on the second story. Strong dental molding crowd the tops of the second-floor windows, while a row of five identical dormers gave the structure a top-heavy look. A covered porch extended to the east, supported by Doric columns. As a cost-saving measure, the entire structure was built of wood. It was replaced in 1913.

Mrs. and Mrs. Charles A. Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. Louis XIII style. Alterations, 1930. Razed, 1960s.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. View of house from Lake Michigan.

David Adler when a young man.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. Terrace façade.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A. Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. Dining Room. English walnut paneling with hand-carved walnut table and high back upholstered chairs.

Original entrance to Stonehill Mansion on Sheridan Road in Glencoe, Illinois. It sat on more than 19 acres on Lake Michigan. In 2016 North Shore Congregation Israel Temple is on the site.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A. Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. RAZED in the 1960s.

David Adler, Stonehill (called Pierremont), Entrance Hall. The Stonehill family lived at the estate until the Crash of 1929.

The Château de Balleroy is a seventeenth-century château in Balleroy, Normandy.

One of two stone rams at the entrance to courtyard at Stonehill mansion. Landscape architect Jens Jensen (1860-1951) designed several gardens at the mansion.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A. Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. Music Room. Louis XVI paneling and parquet-de-Versailles flooring with Louis XV furnishings.

Members of the Household Staff at the Charles A. Stonehill Estate. The mansion was demolished in the 1960s.

Garden trellis at the Charles A. Stonehill estate in Glencoe, Illinois.

Inspired by the Chateau de Balleroy in northern France, Charles A. Stonehill commissioned his son-in-law David Adler to design and build this Louis-XIII style building. Set high on the bluff overlooking Lake Michigan, this home was a popular weekend destination by many of Chicago’s elite in the 1910s.

Members of the staff of The Charles A. Stonehill Estate on the beach.

David Adler, Mr/s. Charles A. Stonehill, Glencoe, Illinois, 1911. Drawing Room. Tuscan pilasters. Unique octagonal-shaped coffered ceiling.

Mrs. and Mrs. Ralph H. Poole, Lake Bluff, Illinois, 1912. Louis-XV style. Stands.

Mr/s. Ralph H. POOLE, Lake Bluff, IL, 1912. Adler was influenced by François Mansart (1598-1666) for this early commissioned project.

Floor plan, Poole house, Lake Bluff, Illinois, 1912. Adler placed the five main rooms along the rear of the house with the living room as the central gathering point.

POOLE (Lake Bluff, IL), 1912. Adler’s interior is based on the Hôtel Biron in Paris (today’s Musée Rodin).

POOLE (Lake Bluff, IL), 1912. Living room to music and dining rooms.

POOLE (Lake Bluff, IL), 1912. Dining room.

Mrs. and Mrs. Charles B. Pike, 955 Lake Road, Lake Forest, Illinois. Built in 1916 in the Italian Villa style. Building stands.

The house at 955 Lake Road in Lake Forest, Illinois, sits on Lake Michigan and is designed in the Italian villa style. Built in 1916 for Charles and Frances Pike, the 21-room house possesses one of Adler’s most successful outdoor spaces – the entrance Courtyard.

Creating paths using paving beach stones with embedded designs, this outdoor garden was encapsulated on four sides by the back wall of the house (the main entrance which faces the road) as well the Kitchen, classically-proportioned Entrance Loggia and fifty-foot-long Gallery.

The Courtyard was further integrated with the interior space where one enters the house’s main rooms from the Entrance Loggia into the Vestibule (with Adler’s masterful treatment of pediments and coffered ceiling) or by way of one of three sets of French doors with pilaster-supported archways into the vaulted Gallery.

In addition to the Vestibule and Gallery with its airy fifteen foot-tall ceilings, the interior first-floor plan of the Pike house contained the Living Room, Dining Room and East Loggia. Each of these main rooms was oriented to the balustraded landings of two staircases which led to an expansive sunken garden and towards Lake Michigan. The second floor of the Pike house contained bedrooms.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest, Illinois. 1916. Entrance Facade.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Entrance Loggia.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Entrance Loggia, another view.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Courtyard.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Courtyard with view of his design of the pavement using beach stones creating an interplay of color, texture, and shape.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Vestibule. From the Entrance Loggia one enters the house’s main rooms into this Vestibule with Adler’s masterful treatment of pediments and coffered ceiling.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Gallery.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Living Room (or Library). The black stone fireplace mantel was the focal point of the room.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Living Room (or Library) in recent times.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Dining Room. The same size as the as the Living Room, the black terrazzo floor was consistent on the first floor, but Adler achieved greater intimacy with the beamed ceiling.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Dining Room today.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Garden/Main Facade. The house was inspired by Charles A. Platt’s Villa Turicum from 1908, but Adler turned the Pike house’s orientation to the Lake and away from the road.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Sunken Garden. Looking toward Lake Michigan.

D. Adler. Pike House. Lake Forest. 1916. Garden/Main Facade today.

Mrs. and Mrs. Alfred E. Hamill, Lake Forest, Illinois. Built by Henry Dangler in 1914 in the Italian style and renovated by David Adler in 1917. Building stands.

When Adler became involved in the project, the Hamill House added two bronze centaurs on pedestals at the foot of the driveway introducing its new brick and limestone forecourt. A more dramatic change was the installation of the false parapet that heightened the house and hid its tiled roof.

Adler added the library to the west wing with steps going down to it from the living room. Warm and inviting the library had tall walnut bookcases and a hemispherical niche. One door opened to a staircase leading to Hamill’s second-floor bedroom. The fireplace was detailed in black marble and limestone with a pediment mantel. Over time Adler directed interior changes that included a breakfast room and music room.

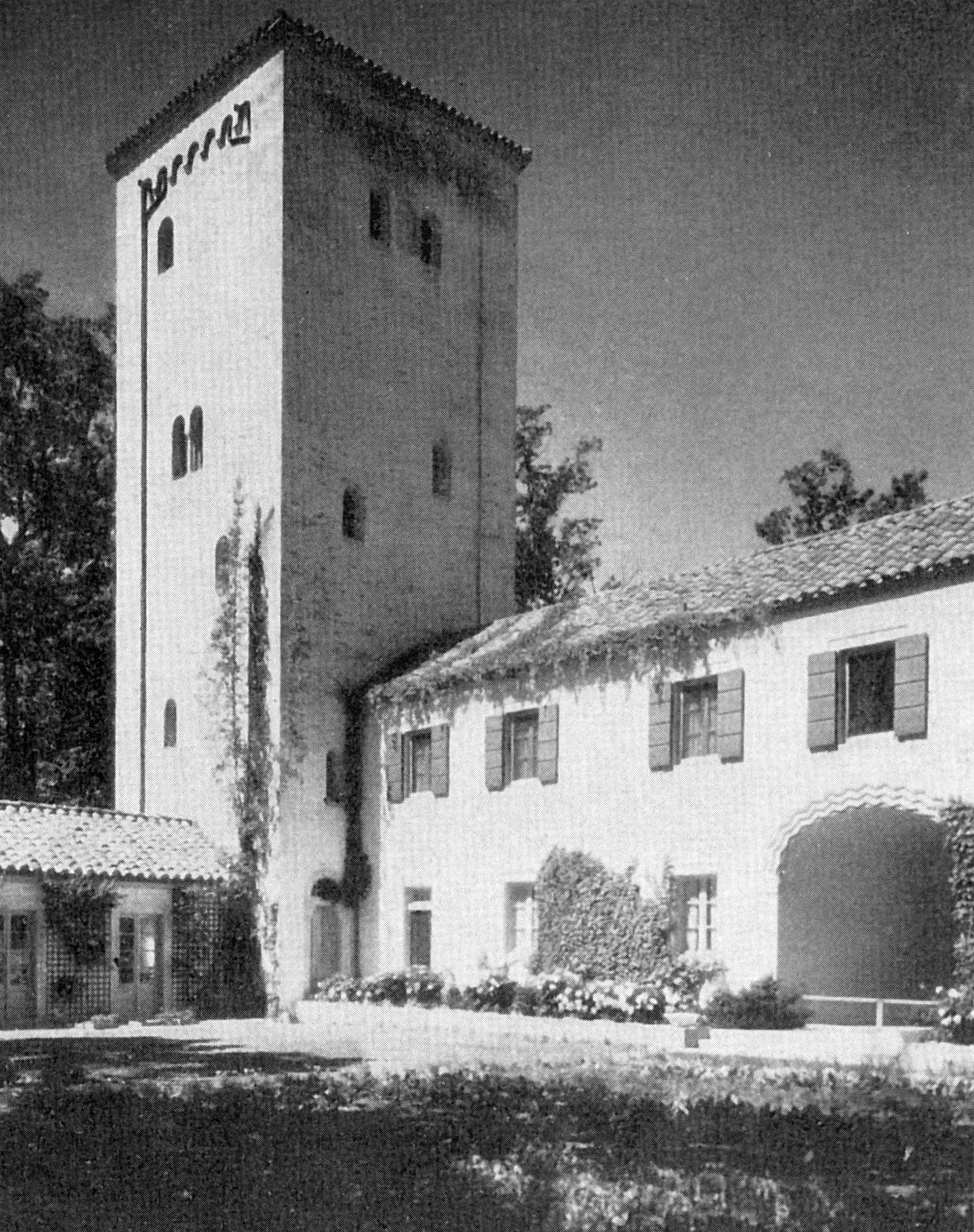

Into the 1920’s Hamill — an investment banker and the man who introduced Adler to involvement with the Museum of The Art Institute of Chicago — continued to make grandiose changes to his house. Some included adding a tower building and garage and servants’ quarters in the same Italian design as the main house. The tower stood almost seventy-five feet tall and included Alfred Hamill’s study.

Alfred Hamill’s study in the Italian-style tower by David Adler in the 1920’s is reminiscent of Napoleon’s tented study at Malmaison in France.

Another of Hamill’s improvements in the 1920’s was a Palladian-designed Garden Pavilion with limestone open summerhouse and cylindrical posts encircled by stairs leading to a deck. Today the Hamill House as well as its tower and garden pavilion stand, but are separate properties.