FEATURED image: Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), The Kite (detail), 1777/78. Oil on canvas, 269 x 285 cm.

These are a selection of the first two suites of decorative tapestry cartoons (or designs) completed for El Escorial in 1775 and El Palacio Real del Pardo between 1776 and 1778 by Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) .

Both of these palaces were the residences of the future Carlos IV (reigned, 1788-1808) and his wife, Queen consort of Spain, María Luisa de Parma—they are the Prince and Princess of Asturias for whom the artist did these works.

1. DINING ROOM OF THE PRINCES OF ASTURIAS IN SAN LORENZO DE EL ESCORIAL, 1775.

1. Decoy Hunting 1775. Oil on canvas, 112 x 179 cm.

The cartoon called Decoy Hunting is part of the first commission that Goya received for the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Bárbara in 1774-1775.

It was part of a series of fourteen tapestries—of which Goya rendered nine of them. They depicted hunting subjects, a keen passion for the Spanish nobility, to hang as decoration in the dining room at El Escorial of the Prince and Princess of Asturias.

Newly arrived to Madrid in January 1775 , Goya completed and submitted his cartoons for this commission between May and October 1775.

The cartoon called Decoy Hunting is part of the first commission that Goya received for the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Bárbara in 1774-1775.

It was part of a series of fourteen tapestries—of which Goya rendered nine of them. They depicted hunting subjects, a keen passion for the Spanish nobility, to hang as decoration in the dining room at El Escorial of the Prince and Princess of Asturias.

Newly arrived to Madrid in January 1775 , Goya completed and submitted his cartoons for this commission between May and October 1775.

2. Dogs on a leash 1775. Oil on canvas, 112 x 174 cm.

This is Goya’s tapestry cartoon of two hunting dogs chained together—one of which sits up and holds a fixed gaze on the viewer—with hunters’ tools on the ground. It is part of a series of decorative tapestries depicting hunting subjects for the new Bourbon rooms installed in 1773 by the architect Juan de Villanueva (1739-1811) at El Escorial.

Goya, newly arrived to Madrid from Zaragoza in 1775, was brought into the project because one of its originators, Ramón Bayeu y Subías (1746-1793), after having completed five of the intended fourteen cartoons by March 1775, was appointed to assist painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728–1779) at El Palacio Real de Madrid in the execution of several frescoes there.

Goya rendered the remaining nine cartoons, six of which are included in this blog post.

3. Hunting Party 1775. Oil on canvas, 290 x 226 cm.

Hunting Party is one of the nine cartoons Goya provided for the royal dining room at El Escorial. This cartoon scene displays different types of hunting.

While Goya worked closely with the designs of Ramón and elder brother Francisco Bayeu y Subías (1734-1795), the originators of this project, the young artist placed his own stamp upon the commissioned work.

For instance, in the background, Goya’s sprinting greyhound provides an original and engaging study of how to represent rapid animal movement in a painting.

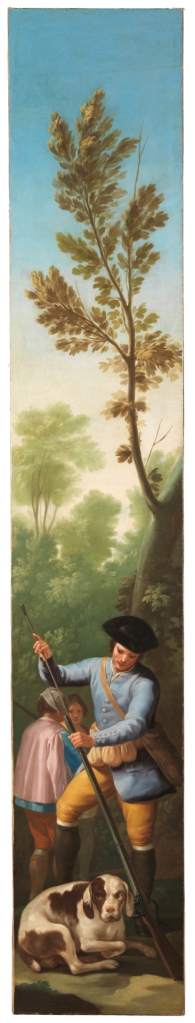

4. Hunter with his Hounds 1775. Oil on canvas, 268 x 67.5 cm.

The two cartoons below called Hunter with his hounds and Hunter Loading his Rifle are paired for a tapestry in El Escorial to hang by a window or door.

The cartoon is notable in part for Goya’s successful rendering of a hunter depicted from the back with a rifle on his shoulder and two leashed dogs — a “modern figure in a landscape.” Goya’s late 18th-century artistic accomplishment became a leading challenge for later 19th century French Impressionists such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) to attempt the same sort of figural art work.

5. Hunter loading his Rifle 1775. Oil on canvas, 292 x 50 cm.

Goya’s cartoon is called Hunter loading his rifle. It is paired with Hunter with his hounds. the cartoon depicts a face-forward hunter with a sitting dog who stares at the viewer. In the background are others in the hunting party.

The design is for a dining room tapestry at El Escorial for the future Carlos IV (1748-1819) and his wife, María Luisa de Parma (1751-1819).

6. The Angler 1775. Oil on canvas, 289 x 110 cm.

Two activities are represented in this cartoon scene—fishing and hunting. A transition between them is marked by the sports’ different tools that overlap in the middle of the canvas.

The Angler completed the commission begun in 1774 by Francisco and Ramón Bayeu to prepare a set of fourteen tapestry cartoons for the decoration of the dining room of the future Carlos IV and María Luisa de Parma at El Escorial, of which Goya produced nine of them.

The theme of hunting was specifically selected to merge with the monarchs’ use of El Escorial in the autumn as a hunting grounds.

Two activities are represented in this cartoon scene—fishing and hunting—with a transition between them marked in the sports’ different tools overlapping in the middle of the canvas.

The Angler completed the commission begun in 1774 by Francisco and Ramón Bayeu to prepare a set of fourteen tapestry cartoons for the decoration of the dining room of the future Carlos IV and María Luisa de Parma at El Escorial, of which Goya produced nine of them. The theme of hunting was specifically selected to merge with the monarchs’ use of El Escorial in the autumn as a hunting grounds.

2. DINING ROOM OF THE PRINCES OF ASTURIAS IN THE PALACE OF EL PARDO, 1776-1778.

7. The Picnic 1776. Oil on canvas, 271 x 295 cm.

The Picnic is part of Goya’s 10-tapestry decorative cartoon series depicting leisure in the countryside for a dining room tapestry at El Pardo for the Prince and Princess of Asturias.

Notable for its foreground still life, this scene depicts young revelers sitting on the banks of the Manzanares River at Madrid’s periphery.

The Picnic is joined in Goya’s second cartoon series by Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares, A Fight at the Venta Nueva, An Avenue in Andalusia (or The Maja and the cloaked Men), The Drinker, The Parasol, The Kite, The Card Players, Children blowing up a Bladder, and Boys picking Fruit.

8. A Fight at the Cock Inn 1777. Oil on canvas, 41.9 x 67.3 cm.

An early draft called El Mesón del Gallo by Goya for his preparatory sketch for the cartoon of A Fight at the New Inn.

Goya’s artistic models for the cartoon range from typical seventeenth century Flemish and Dutch genre scenes to elements of Italian classicism.

The 32-year-old Goya displays a creative edginess in a tapestry that is to hang in the royal house. The artist presents a brutal and ironically humorous scene showing country folk from diverse regions of Spain and of varying social roles using several weapon types to violently contest a card game involving money.

9. Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares 1776 – 1777. Oil on canvas, 272 x 295 cm.

The resulting tapestry was to be hung on a wall of the dining room at the Palacio de El Pardo in Madrid for the princes of Asturias. Progressing from his hunting cartoon suite done on behalf of the brothers Bayeu the year or so before, this 10-part series of country life scenes was completely Goya’s own invention.

Goya’s cartoon called Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares depicts a scene of majos and majas (country folk) dancing the seguidillas, a dance that was popular in Madrid and throughout Spain’s Castile region.

The view of the river banks and the figure of the man clapping his hands are composition elements preserved in Goya’s drawing notebook suggesting they were taken from life.

10. Children blowing up a Bladder 1777 – 1778. Oil on canvas, 116 x 124 cm.

The tapestry resulting from this cartoon hung in the dining room of the future Carlos IV and Queen consort María Luisa de Parma in El Palacio de El Pardo in Madrid.

With his cartoon Goya started his childhood scenes in this series of ten tapestries of “country” subjects for the royal house.

In a playful yet dramatic scene, a boy of about 7 years old inflates an animal bladder as his companion awaits the outcome raising one hand to her heart.

Two women seated in the background are perhaps the children’s mothers. One of the women displays a melancholic disposition as she holds a hand to the head while the other looks straight at the viewer.

11. An Avenue in Andalusia or The Maja and the cloaked Men 1777. Oil on canvas, 275 x 190 cm.

This tapestry cartoon presents an ostensible love scene of a well-dressed young woman with her companion. in the tapestry factory invoice Goya identified both figures as gitanos, or gypsy people.

The scene is populated with other stealthily dressed figures, perhaps with their own sinister intent, suggesting an undercurrent of jealous spying on the gitano pair.

For a Madrid royal palace’s dining room (El Pardo), Goya considered this scene a fanciful contemporary walk in far-off Andalucia in southern Spain.

12. The Parasol 1777. Oil on canvas, 104 x 152 cm.

A bottom-to-top perspective view joined to its format indicates that this tapestry cartoon for the El Pardo dining room was intended to decorate an over-arch.

A cortejo holds a green-color parasol to shade an elegant young woman from the Iberian sunshine.

Goya’s cartoon could have possibly been modeled on the work of Jean Ranc (1674–1735), a French portrait painter or on a lunette entitled Vertumnus and Pomano by Italian painter Pontormo (1494-1557).

If it is the Pontormo that inspired Goya then, in this instance, the artist creatively transformed what was an ancient mythological subject into a scene of modern Spanish life.

13. The Kite 1777 – 1778. Oil on canvas, 269 x 285 cm.

In this mid-to-late eighteenth century contemporary scene, possibly drawn from life, Goya describes it as young people who “have gone out to the field to fly a kite.”

A majo is smoking, body splayed upon the ground, sending smoke into the air. In the cartoon’s center three majos fly the popular kite with a sun face on it. One figure holds the spindle, another guides its string, and a third in heroic stance, launches and maintains the kite aloft.

In the background, couples chat and watch the kite’s flight, while a dog sits and looks towards the viewer.

The building in the cartoon’s upper right part has been interpreted as an astronomical observatory, a scientific project popularly spoken of in the days of Carlos III (1716-1788).

14. The Drinker 1777. Oil on canvas, 107 x 151 cm.

A cartoon for a tapestry in the dining room in the Palace of El Pardo in Madrid, one of a series of ten made by Goya between 1776 and 1778.

The scene has been interpreted as has been seen as Goya’s allegory of gluttony. A young man drinks from a boot and a boy eats a raw turnip snatched out of a collection of meager vegetables with a round loaf of bread that constitutes the cartoon’s still life.

These images would be based on characters from a 1554 Spanish novella entitled The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities. The novella tells the story of a boy named Lazarillo who learns the world’s wiles from a blind beggar with whom he is apprenticed.

The format and bottom-to-top perspective view indicates the modern tapestry cartoon was for an over-window decoration.

15. Boys picking Fruit 1778. Oil on canvas, 119 x 122 cm.

Boys picking Fruit is another of Goya’s childhood scenes. It is one of four scenes of a set with Children blowing up a Bladder, The Parasol, and The Drinker which hung as overhead decorations in the dining room at El Pardo.

The joyful and playful cartoon depicts four boys gathered at a tree to shake down its fruit. It is part of a series of ten tapestry cartoons of “country” subjects—all conserved in the Prado Museum in Madrid—that Goya composed and produced.

16. The Card Players 1777 – 1778. Oil on canvas, 270 x 167 cm.

To give this scene an appearance of realism, Goya carefully crafted each individual face and unique expression for each figure. These creative details enriches the depiction of country folk cheating and being cheated at cards.

Goya’s accurate study of the contrast of light and shadow enhances his varied colors which works to heighten the scene’s realism.

A group of majos situate themselves in a field as three of them play card. They gather under a man’s cloak placed on a tree branch which shadows them from the sun at siesta.

With gold coins tossed into a hat on the ground by one of the players, the two other majos study their hands, each with an expression of concern.

Darkly humorous, the cartoon revealed to its viewer the accomplices standing behind two players and who are sending signals to a third player about the unsuspecting victims’ cards.

The Card Players concludes Goya’s 10-part cartoon series of scenes of country life for the tapestries in the dining room of El Pardo for the princes of Asturias.

CONCLUSION.

Between 1775 and 1792, Goya painted more than 60 cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory located in Madrid since 1720. (It moved to its present site by the main train station in the nineteenth century). Like Les Gobelins, an older counterpart in Paris, the Royal Tapestry Factory supplied the Spanish royal court with tapestries which were among the most prestigious objects owned by them.

By the late eighteenth century, large tapestries were hung in palaces mainly for decoration. Goya’s contemporary scenes from that period illuminated newly-built Bourbon rooms at El Escorial and the dining room at El Pardo.

In 1775, that the Prince and Princess of Asturias were hanging tapestry scenes about the hunt—an activity that would become the future Carlos IV’s passion —or about peasant life had been the fashionable choice for the ruling class for around two hundred years already.

For Goya’s designs to display the artist’s playfully sensuous inventions joined with a dark and ironically humorous wit—along with the candid appreciation of the modern scene based on first-hand observation (especially the costumes) as well as using stock social characters doing things that can intelligently impress and amuse a royal audience and their guests—makes these disposable cartoons the more remarkable.

Further, the fact that they were retrieved largely intact from the basement of a Madrid royal palace almost a century after Goya’s death and are now housed in the Prado makes their firsthand study in the 21st century altogether amazing.

SOURCES:

On Goya’s cartoons:

https://www.goyaenelprado.es/obras/lista/?tx_gbgonline_pi1%5Bgocollectionids%5D=5-56;

Goya, Robert Hughes, Knopf, New York, 2003.

On tapestries:

http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/exhibitions/divineart/usefunctap;

http://www.millefleurstapestries.com/en/history-of-tapestries.