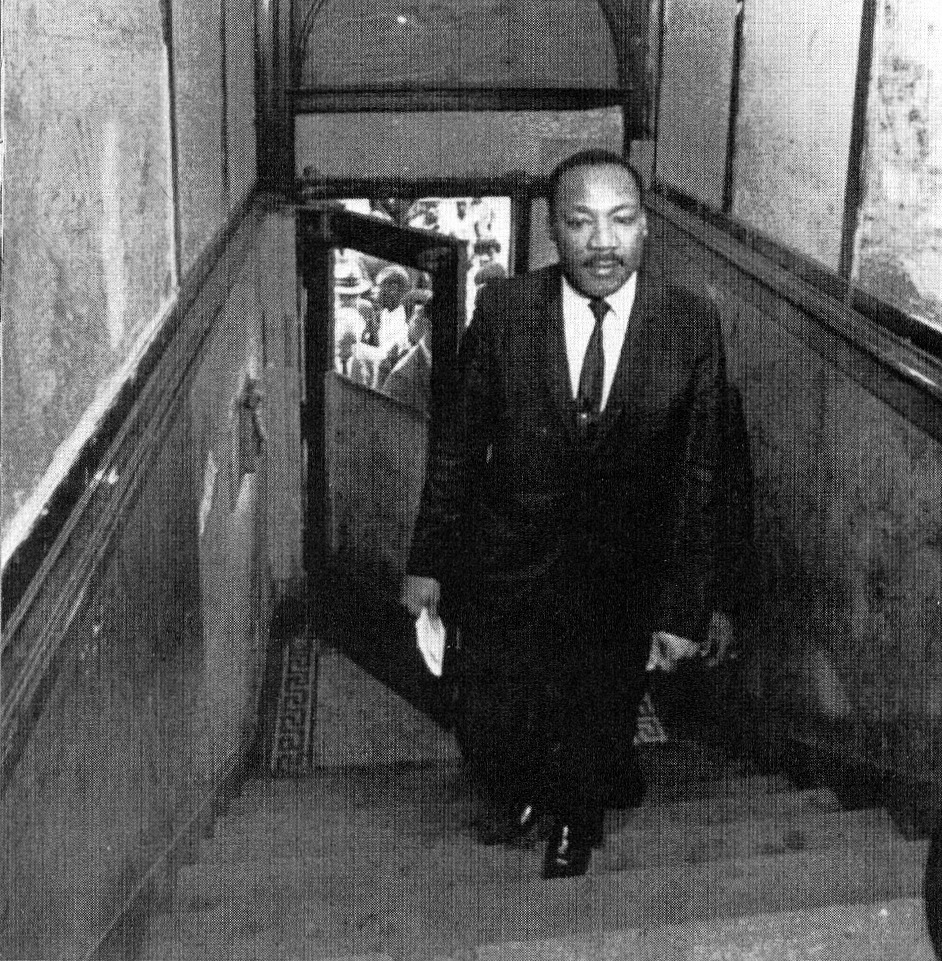

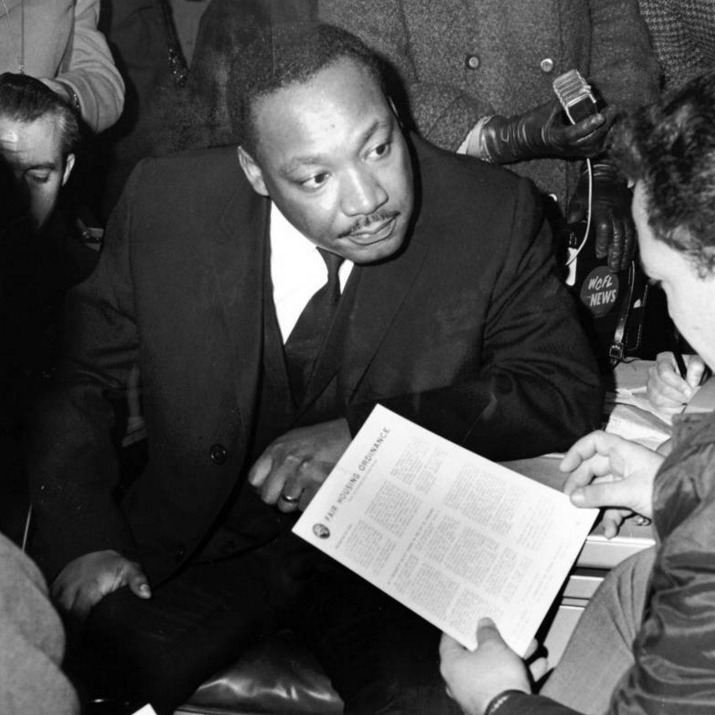

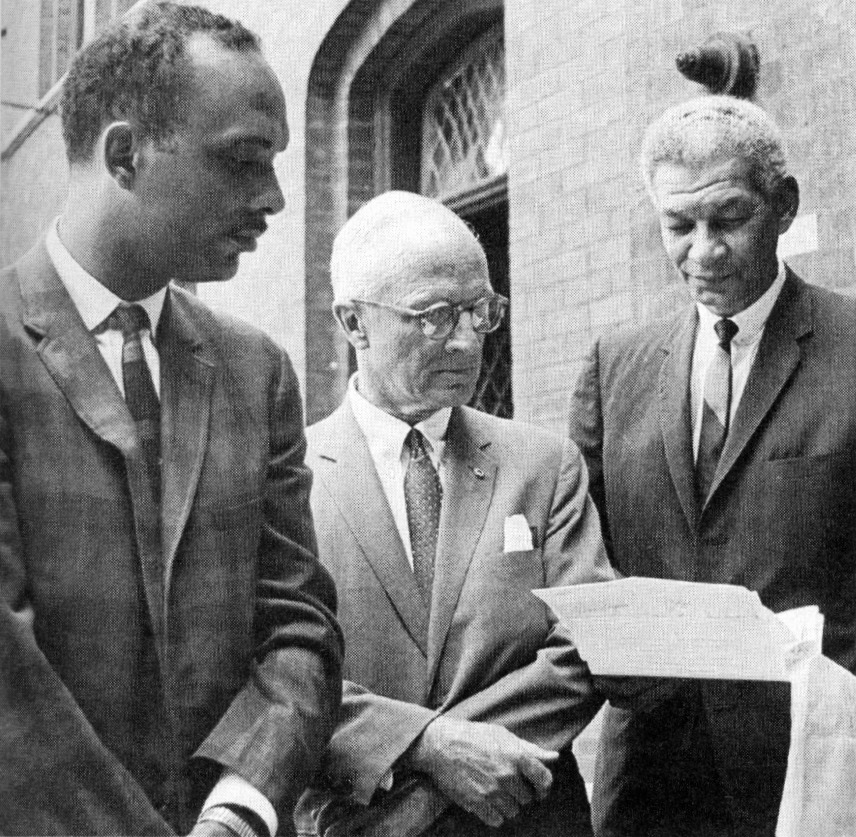

FEATURE image: At Chicago’s City Hall, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Chicago Freedom Movement leaders, July 10, 1966. Following a speech in front of thousands at Soldier Field and a march downtown, Dr. King presented Mayor Daley with fourteen demands for a racially open city.

August 5, 2016 – by John P. Walsh.

Released on July 4, 1966 The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Summer in the City” reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in August 1966 and stayed there for three consecutive weeks.1 “Hot town, summer in the city, back of my neck getting dirty and gritty, been down, isn’t it a pity, doesn’t seem to be a shadow in the city. All around, people looking half dead, walking on the sidewalk, hotter than a match head…”

In Chicago in 1966 Dr. King promised a summer of nonviolence but that didn’t stop a white Chicago policeman from shooting and killing a 21-year-old Puerto Rican on June 10, 1966 and sparking a riot of the victim’s neighbors who looted stores, torched squad cars and assaulted firefighters called out to quell the blazes. A month earlier Stokely Carmichael, elected by a razor-thin margin over John Lewis to lead the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, pronounced a new Black Power movement that ended that organization’s interracial efforts.

While the Chicago Freedom Movement remained staunchly interracial King warned Daley on July 9, 1966 that the mayor’s aloofness towards fundamental improvements for African-Americans in Chicago could lead to more radical black groups making their own demands. Since black Chicagoans were, despite a fair housing ordinance, mostly restricted to the ghetto where landlords charged higher rents to a captive market, King’s allies believed open access to Chicago’s real estate market was necessary to tackle larger problems of slums, unemployment, and underprivileged schools.

Chicago, Illinois, summer 1966 (AP Photo). In the foreground is the Shangri-La with its parking garage and deck at 222 N. State Street. Billed on its matchbooks as “the world’s most romantic restaurant” the Far Eastern/Polynesian themed establishment opened in 1944 and closed in 1968. The 65-story Marina Towers (background) opened in 1963. When completed in 1968 the twin towers were both the tallest residential buildings and the tallest reinforced concrete structures in the world.

Released on July 4, 1966, The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Summer in the City” reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 in August 1966 and stayed there for three consecutive weeks.

Mayor Richard J. Daley views the Chicago skyline in 1966 from atop the new Daley Center. Daley was focused on downtown development in the mid-1960’s and viewed King largely as an outsider with his own political agenda who simplified complex urban social problems for which Chicago was not completely at fault.

Martin Luther King Jr., with Stokely Carmichael in Mississippi in 1966. Although King saw Carmichael as a most promising young leader, in May 1966 Carmichael declared a new Black Power movement that ended the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s interracial efforts. The Chicago Freedom Movement to which King was attached stayed staunchly interracial.

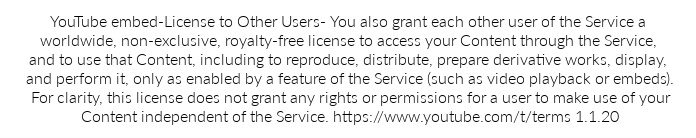

Dr. King exits the tenement apartment at 1550 S. Hamlin on Chicago’s West Side where his family stayed during the Chicago Freedom Movement in 1966. American Friends Service Committee found that white and black families paid about the same in monthly rent but whites earned half as much more as what blacks earned. They found that for the same money blacks on average lived in about 15% less space (3.35 to 3.95 rooms). King looked to solve these and other socioeconomic discrepancies in his 1966 Chicago sojourn.

1550 S. Hamlin on Chicago’s West Side, the redeveloped site where King and his family stayed during the Chicago Freedom Movement in 1966. Screenshot October 29, 2018.

Mathias “Paddy” Bauler who in 1955 famously quipped that “Chicago ain’t ready for a reform mayor”2 was still an active Northside Chicago alderman in 1966. To some Chicagoans, Bauler’s colorful quip should have been Mayor Daley’s prevailing opinion towards open housing. In July and August 1966 King’s street marches into the white-only neighborhoods of Gage Park, Marquette Park and Chicago Lawn3 were intended to showcase the Chicago Freedom Movement’s reform message of open housing.

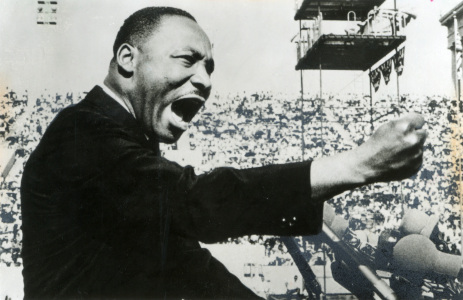

Following a rally at Soldier Field on Sunday, July 10, 1966 where King spoke to thousands of supporters including these words, “we will no longer sit idly by in agonizing deprivation and wait on others to provide our freedom,”4 he then led thousands on a march to City Hall. Marching peacfully three miles from the lakefront into downtown, King posted the Chicago Freedom Movement’s fourteen demands for a racially open city at City Hall. The next day Daley met with King but the pair, who personally respected one another, floundered at an impasse.

King was impatient for direct action but Daley was passive and noncommittal. Afterwards King made clear to Daley that these were 14 demands, not suggestions. From Daley’s viewpoint, King was a public relations disaster for Chicago because he was an outsider articulating simple solutions to complex and not always only local social problems. King indicated an inclination that it was time to march into the neighborhoods.

Sunday, July 10, 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. delivers a 12-page speech at a rally for civil rights at Soldier Field in Chicago that drew tens of thousands of supporters of open housing, better education and increased employment opportunities for the city’s black community. Photo: the Sun-Times archives.

The crowd and Dr. King at the Chicago Freedom Movement rally on Sunday, July 10, 1966, at Soldier Field. Photograph by Bernard Kleina.

Following a rally for civil rights at Soldier Field in Chicago where Dr. King addressed the crowd on Sunday, July 10, 1966, thousands marched through downtown Chicago to City Hall.

The march ended when the list of demands was nailed to the door of Chicago’s City Hall.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Chicago’s City Hall on July 10, 1966.

King met with a passive and noncommittal Daley in City Hall on Monday, July 11, 1966 (this photo, March 24, 1966). The antagonists met infrequently in 1966 to address The Chicago Freedom Movement’s issues and each time King left with vague, piecemeal promises for change.

On July 14, 1966, three days after the Daley-King meeting, a drifter named Richard Speck tortured, raped, and murdered eight female student nurses from South Chicago Community Hospital on the south side of Chicago. Speck, born in an Illinois farm town in 1941, lived in Dallas for the last 15 years and, running from the law there, only arrived into Chicago in April 1966. In the pall of a July heatwave, the serial killer was on the loose in the city for three days – a police sketch plastered everywhere in newspapers and on TV – until he was arrested on July 17, 1966. These gruesome killings were called “The Crime of the Century” and added panic, gloom and a general fear to an already tense city.5

Two weeks later, on August 1, 1966, in Austin, Texas, Charles Whitman, shot 49 victims from the bell tower of the University of Texas, killing 17 – and brought the term “mass shooting” into the American popular discourse.

These violent crimes precipitated ramped-up tension in Chicago and the nation in the hot and muggy summer of 1966. Already gripped by an escalating Vietnam War as well as massive civil rights movements, women’s rights movements, youth counter-cultural movements, and even radical church reform (“Vatican II”) movements, American society was swiftly and increasingly wrapped into a tight fist of revolutionary social change whose resistance to it tended to exacerbate the possibility of what King called “social disaster.”

Violent crimes of mass murderers Richard Speck in Chicago in midJuly 1966 and Charles Whitman in Texas in August 1966 worked to ramp-up tension people felt in Chicago during the long, hot summer of 1966.

Speck’s horrendous crimes came in the same week when Chicago police shot and killed two black Chicagoans, including a pregnant 14-year-old girl, during riots on the predominantly black West Side that Daley blamed on King. King denied any such connection and told Daley that if it wasn’t for the Chicago Freedom Movement’s preaching nonviolence those riots would have mushroomed into another Watts. To King’s way of thinking these disturbances among a swath of the city’s population should serve as the clarion call to Daley to act boldly on behalf of the black community and begin to enact the 14 demands brought to him to make Chicago a racially open city.6

Instead Daley’s response was to mobilize 4,000 members of the National Guard to restore law and order. In the wake of the violence—with police brutality blamed by the police on the rioters—another meeting between Daley and King took place where they agreed on a handful of reforms– (1) to establish a citizen’s advisory committee on police and community relations; (2) that grassroots workers go door to door in riot-affected areas to advise calm; and, (3) a new investment to build more swimming pools in black areas.

King was unimpressed with what he considered Daley’s lackadaisical approach and local media mocked the mayor’s feeble plan.

“Get Ready” by Smokey Robinson was recorded by The Temptations in December 1965 and released in February 1966. It landed at no.1 on the Billboard R&B singles chart and reached no. 29 on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart. The up-tempo dance number was led by the falsetto of The Temptations’ Eddie Kendricks. Since The Temptations were formed in Detroit, Michigan, in 1961, the male vocal group has proven to be one of rock history’s most enduring groups who are unparalleled in their artistic and commercial success.

For his part, King started “walking,” that is, organizing marches into the city’s largely white neighborhoods adjacent to black ones so to highlight the need for open housing. KIng also re-started talks with Chicago gang members to convince them to forsake violence and join his nonviolent racially integrated movement.7

Since Daley viewed Chicago as having more accomplishments than problems in the area of race relations and that, further, the Mayor publicly considered the outsider King to be a selfish agitator, many white residents of soon-to-be-marched-upon city neighborhoods assumed Daley would take their side.

But Daley’s politics of law and order and incremental social change succeeded in alienating almost everyone. In the Chicago mayoral election in 1967 black voter turnout and support for Daley disappeared and did not return for him in subsequent mayoral contests in 1971 or 1975. Meanwhile, white residents felt the fatal sting of being “betrayed”8 by the city powers as Daley did not stop the marches from going forward.

The north edge of Marquette Park in early 2016. Photograph by author.

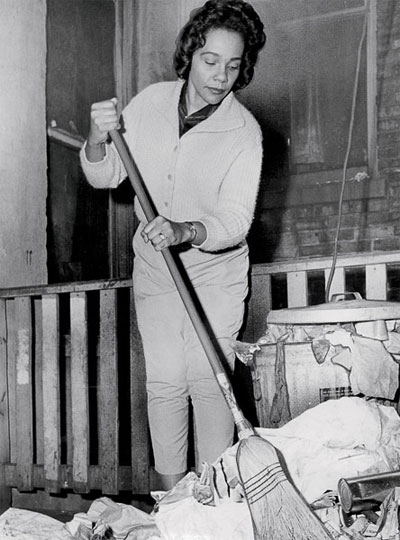

The Rev. Martin Luther King and Chicago building janitor Robert DeBose, left, discuss the eviction of families from the building. DeBose contended the families were evicted for not paying rent.

The first march was on Saturday, July 16, 1966 when a group of 120 demonstrators marched from Englewood into Marquette Park “for a picnic.” The next day, Sunday, July 17, 1966 about 200 marchers, taunted by neighborhood whites, held a prayer vigil outside a Gage Park church. Almost two weeks later, on Thursday, July 28, 1966, protesters began an all-night vigil at 63rd Street and Kedzie Avenue at a realty company that systematically discriminated against black buyers looking to move into Gage Park. The realtors had been reported to the Chicago Commission on Human Relations but nothing happened. White counter demonstrators appeared and with nightfall Chicago police struck a deal for the lawful open housing (or open occupancy) protesters to file into paddy wagons for safe escort back to the ghetto.

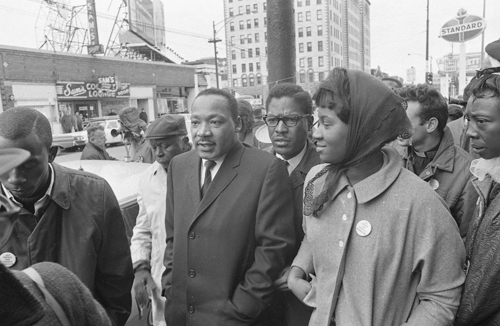

Dr. King attended two marches in Marquette Park on August 5, 1966 and, shown here, South Deering on August 21, 1966.

Movement leaders Al Raby (left), James Bevel (second from right) and Jesse Jackson (center) protest in front of the Chicago Real Estate Board in downtown Chicago.

Chicago Lawn white hecklers during a Chicago Freedom Movement march in summer 1966.

Chicago Police in Marquette Park on August 5, 1966. Their presence did not prevent severe rioting by white mobs that day.

On July 30, 1966 about 250 open housing protesters, furious about the recent night’s humiliation, looked to return to the same southwest side intersection. They were met by bottles and rocks thrown by whites so that the protesters retreated again east of Ashland Avenue into Englewood. When demonstrators marched out of Englewood again on July 31, 1966 more than 500 whites met them as the protesters crossed Ashland Avenue on 63rd Street. Armed with cherry bombs, rocks, bricks, and bottles, the surly mob grew to over 4,000 whites where they burned cars and injured around 50 open-occupancy protesters, including a first grade teacher hit by a projectile.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Jesse Jackson in Chicago. King holds a Chicago Daily News with a headline that reads “City Seeks To Cut Marches.”

On August 2, 1966, Daley met with white homeowner groups from the southwest side. In addition for calling for law and order from blacks and whites, the mayor acknowledged the open housing protesters had a legal right to march. Daley, through an intermediary, sent King modest housing improvement and integration proposals which King rejected and Daley implemented anyway. Daley next sent to an embattled King some local black aldermen who opposed the Chicago Freedom Movement but carried more substantial housing and employment offers from City Hall. The city government hoped that King, who was known to be looking for a way out of Chicago with a tangible victory, might accept a negotiated pact and call an end to the campaign. With these serious talks going on between Daley and King, the late summer marches for open housing continued under an increasingly vicious white backlash.

A white mob attacks a car during the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s August. 5, 1966 march to Marquette Park. Photo by Bernard Kleina.

White rioters encountering Chicago police at a Clark gas station in Marquette Park on August 5, 1966. A Confederate flag is on the right. Photo by Bernard Kleina.

Whites moving east on 63rd Street to confront marchers on the way to Marquette Park on August 5, 1966. The Clark gas station in the background is the site of the photos by Bernard Kleina.

The infrastructure of the former Clark gas station still exists today on 63rd street (July 2018). Screen shot dated October 29, 2018.

The old Clark gas station looking east on 63rd Street at Whipple. Screenshot October 29, 2018.

On Friday, August 5, 1966, Al Raby and Mahalia Jackson led a group of about 500 open occupancy protesters into Marquette Park in south Chicago Lawn. A white mob of over 10,000 had gathered there and verbally abused the marchers and then turned physically violent. King, who up to this point had not participated in these marches, arrived and joined the march on the north side of the park. It was here, between Francisco and Mozart Streets south of Marquette Road that Martin Luther King was struck in the head behind the right ear by a baseball-sized rock and felled to one knee.

The open housing marchers, angry and disgusted, made their way the short distance out of the park and towards 63rd and Kedzie where King dodged a knife thrown at him. The crowd began to shout “Kill him!” as well as other racially charged epithets and about 2,500 whites now started throwing bottles, burned cars, smashed bus windows and clashed with police for the next five hours.

King with (from left) Mahalia Jackson, Jesse Jackson, and Al Raby at the New Friendship Baptist Church at 848 W 71st St in Chicago —the staging point for the 3 and a half miles walk to Marquette Park —on August 4, 1966. Photo: Chicago Tribune.

Marching south down Kedzie Avenue to Marquette Park in Chicago on August 5, 1966. Bourne Chapel is located at 6541 S. Kedzie, just two blocks from the park. Today the funeral home is gone. The yellow-brick building housing Tony’s Barber Shop in 1966 is still there today, though the barber shop business is gone. Photo by Bernard Kleina.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. falls after being struck by a rock from a taunting white mob in Marquette Park in Chicago on August 5, 1966. King would also dodge a knife hurled at him in the park. King soberly reacted by saying: “Oh, I’ve been hit so many times I’m immune to it.”

Vandals overturn a car before the August 5 march in Marquette Park. Photograph by Jim Klepitsch.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. with supporters in Marquette Park shortly after someone hurled a rock that hit him in the head. Photo by Bernard Kleina.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s comments on that day’s violence entered the annals of civil rights and American history and marks a failing grade for Chicago: “I’ve been in many demonstrations across the south, but I can say I have never seen – even in Mississippi and Alabama – mobs as hostile and hate-filled as I’ve seen in Chicago. I think the people from Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate.”9

A permanent memorial to Dr. King and the Chicago Freedom Movement was erected in Marquette Park on August 5, 2016 for the 50th anniversary of the Marquette Park marches. This MLK Living Memorial at 67th Street and Kedzie Avenue includes a bench to contemplate the 300 tiles created by Chicagoans of all ages representing their understanding of “Home” and representations of a diverse community who continue to work to advance Dr. King’s vision of peace and justice.

In Chicago on Sept. 15, 1966, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr, characterized an open housing agreement reached with Mayor Richard Daley and civic, business and religious leaders “a one-round victory.” King had named Chicago his first target in the North for racial equality in January 1966.

NOTES:

- The Lovin’ Spoonful – Hot 100″. Billboard(Nielsen) 78 (33): 22. 1966-08-13.

- On Mathias “Paddy” Bauler – http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/527.html; Challenging the Daley Machine: A Chicago Alderman’s Memoir, Leon M. Despres and Kenan Heise, Northwestern University Press, 2005, 3.

- In 1960 virtually no blacks – only 7 according to that year’s U.S. Census– lived among a white population of 100,000 in Gage Park/Chicago Lawn/Marquette Park areas – cited in American Pharoah: Mayor Richard J. Daley His Battle for Chicago and the Nation, Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor, Little Brown and Company, New York, 2000, p. 392. Fifty years after the Marquette Park march in 2016, the surrounding neighborhood of Chicago Lawn is a very different place from the all-white enclave King encountered. Whites now account for just 4.5 percent of the neighborhood’s population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. African-Americans make up 49 percent and Hispanics 45 percent –http://chicago.suntimes.com/news/mitchell-rev-martin-luther-king-still-bringing-us-together/- retrieved August 5, 2016.

- Soldier field rally quote- http://www.thekingcenter.org/archive/document/speech-chicago-freedom-movement-rally# – retrieved August 5, 2016.

- On Speck murders – see http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1986-07-06/features/8602180462_1_richard-speck-cab-driver-bags – (and following) retrieved August 5, 2016; See The Crime of the Century: Richard Speck and the Murders that Shocked the Nation,” Dennis L. Breo and William J. Martin, 2016, Skyhorse Publishing.

- Results of West Side riots – American Pharoah, p. 389; Substance of 14 demands – Ibid., p. 385.

- Media mock Daley’s plan and King re-engages gang members– Ibid., 389-391.

- Black voter support declines – Black Politics in Chicago, William J. Grimshaw, Loyola University Presas, 1980, p. 25; whites feel “betrayed” – American Pharoah, p. 394.

- American Pharoah, p. 392-396 and http://sites.middlebury.edu/chicagofreedommovement/don-rose/ – retrieved August 5, 2016.

- C.T. Vivian quotation and text below- Image is Creative Commons CC-BY-SA 4.0.) SOURCE: https://aha.confex.com/aha/2012/webprogram/Paper9589.html

Chicago public school teacher Al Raby (left) of the CCCO and Edwin “Bill” Berry (right) of the Chicago Urban League inspect the open-housing agreement reached in Chicago in late August 1966 with Ross Beatty (center) of the Chicago Real Estate Board. It contained mostly broad volunteer promises for modest integration in all Chicago neighborhoods by the end of 1967, a mayoral election year. At an August 26, 1966 meeting at a downtown hotel with King and Daley both present — and after city faith leaders promised their resolute support of the agreement — Ross Beatty only tepidly endorsed the plan: “Well,” he confessed, “we’ll do all we can, but I don’t know how I can do it.”

June 19, 2022: Video in Marquette Park in Chicago of the Living Memorial taken during my visit.

The Dr. Martin Luther King Living Memorial is on the north side of Marquette Park in Chicago where the park is bisected by busy Kedzie Avenue. It was near this location that Dr. King, as he led protesters into the park during the historic Chicago Freedom Movement march on August 5, 1966, so to protest for open housing, was struck in the head and felled to the ground by a projectile thrown at him by angry white mobs who had gathered and were throwing bottles, rocks and bricks.

The memorial was dedicated on the 50th anniversary of the march (August 5, 2016). It is composed of a plaza, low seating wall, and three carved brick rectangular obelisks by artists Sonja Henderson and John Pittman Weber. The sculptural reliefs depict Dr. King and other prominent community members who marched with him that day.

If you liked this blog post , please visit Parts 1 and Part 2 in the series here:

Also visit the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Quotations Page here: