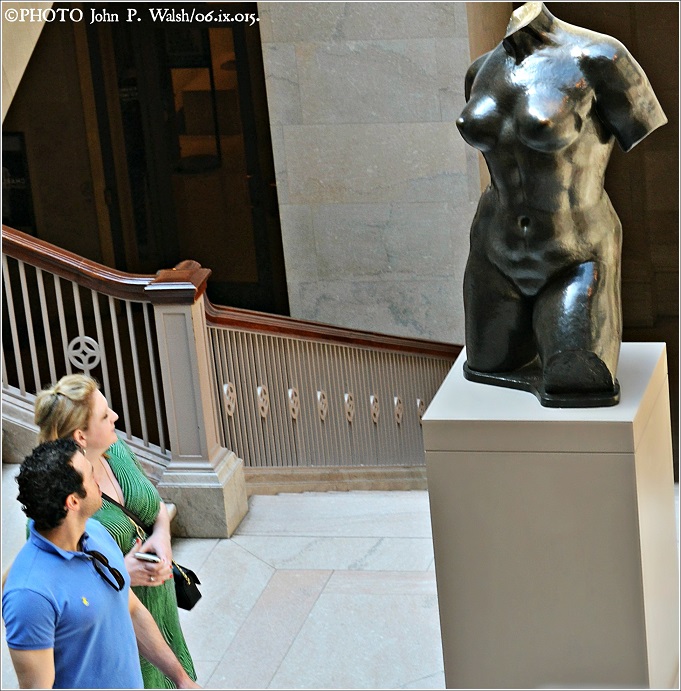

N.B. When this post was published in July 2016, Aristide Maillol’s Enchained Action — a torso cast in bronze and created in 1905 in France — enjoyed a lengthy time on the Women’s Board Grand Staircase at the Chicago art museum. In 2017 the torso was removed by museum curators and placed in an undisclosed location out of public view (see – https://www.artic.edu/artworks/82594/enchained-action). It was replaced by Richard Hunt’s Hero Construction (1958) (see – https://www.artic.edu/artworks/8633/hero-construction).

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

Text and photographs by John P. Walsh.

In September 2016 the Musée Maillol re-opens in Paris following its unfortunate closure due to poor finances earlier in the year. Under the new management team of M. Olivier Lorquin, president of the Maillol Museum, and M. Bruno Monnier, chairman of Culturespaces, the museum’s new schedule calls for two major exhibitions each year which will look to honor the modernist legacy of the artist, Aristide Maillol (French, 1861-1944) and the museum’s founder, Maillol’s muse, Dina Vierny (1919-2009).

This photographic essay called “Encountering Maillol” is constituted by 34 photographs taken by the author in The Art Institute of Chicago from 2013 to 2016 of the artistically splendid and historically notable sculpture Enchained Action by Maillol and random museum patrons’ reactions when viewing it. The impressive bronze female nude from 1905 stands almost four feet tall atop a plain pedestal which greets every visitor who ascends the Grand Staircase from the Michigan Avenue entrance. Enchained Action is one of Maillol’s earliest modernist sculptures and is doubtless filled by a dynamism not encountered anywhere else in his oeuvre.1

Modelled in France in 1905 by a 44-year-old Maillol who by 1900 had abandoned Impressionist painting for sculpture (first in wood, then in bronze) Enchained Action is one of the artist’s most impressive early sculptures. From the start of his sculptural work around 1898 until his death in 1944, the female body, chaste but sensual, is Maillol’s central theme. What can be seen in Enchained Action expresses the intensity in his early sculptural work which is not found later on—particularly the artist’s natural dialogue among his experimental works in terracotta, lead, and bronze each of which is marked by an attitude of robust energy expressed in classical restraint and modernist simplicity. Enchained Action exhibits Maillol’s early facility for perfection of form within a forceful tactile expression which deeply impressed his first admirers such as Maurice Denis (1870-1943), Octave Mirbeau (1848-1917) and André Gide (1869-1951) and cannot fail to impress the museum goer today.2 By force of this new work in the first decade of the twentieth century, Maillol started on the path of becoming an alternative to and, dissonant heir of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917).3

Maillol’s early sculptural work is important for what it is—and is not. Modeled around three years after he completed his first version of La Méditerranée in 1902 in terracotta and for which his wife posed—a major modernist achievement of a seated woman in an attitude of concentration—and whose radically revised second version was exhibited at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, Enchained Action forms part of Maillol’s revolution for sculpture starting around 1900. Maillol made a radical break with neoclassicism and stifling academicism with its strange blend of realism and mythological forms—and with a rising generation of young sculptors such as Joseph Bernard (1866-1931), Charles Despiau (1874-1946) and Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929)—blazed a new path for sculpture. Except for Maillol, all these young sculptors worked in menial jobs for Rodin. Because of Maillol’s chosen artistic distance from Rodin’s work, Maillol did not need to react to it and so rapidly achieved his own new style as soon as 1905, the year of Enchained Action.

Maillol’s concept and primary approach to the beauty of the human body was to simplify and subdue forms. This pursuit began in early 1900 and advanced until the artist’s first time outside France on his trip to Greece in 1908 with Count Kessler (1868-1937). An important early sculpture—Recumbent Nude, 1900—was cast with the help of his lifelong friend Henri Matisse (1869-1954). This friendship had ramifications for the Art Institute’s Enchained Action in that it was purchased from Henri Matisse’s son, art dealer Pierre Matisse in 1955 right after his father’s death. While it would prove quaint for The Art Institute of Chicago to install Maillol’s limbless torso of Enchained Action on The Grand Staircase to pay homage or evoke the Louvre’s Winged Victory or Venus de Milo, it is historically significant so to embody Maillol’s artistic outlook in 1905 for his new sculpture, of which Enchained Action is an example. In the years between 1900 and 1908, Maillol searched beyond realism and naturalism to create sculpture with an abstract anatomical structure that jettisoned the sign language of physical gestures which are emotional and where limbs could be problematic for Maillol’s end design. The human torso of Enchained Action foregoes limbs and head to alone embody and convey the artist’s import for it.4

On The Art Institute of Chicago’s Grand Staircase Enchained Action displays Maillol’s sensitive surface modeling capturing human flesh’s animation and sensual power more than its suppleness as found in Italian masters such as Bernini –such difference serves Maillol’s purpose for his subject matter. The torso is differently pliant—toned, muscular, and strident. It displays the humana ex machina whose stance and posture express the modern hero’s defiance and whose nakedness retains the beauty uniquely imbued in the female human body. Enchained Action is a different work altogether than every work Maillol modeled and cast up to 1905. His art progresses in experimentation by its direct interface with politics. Enchained Action is not only an artwork but a political artwork where Maillol empowers both spheres. For today’s viewer who reacts to nudity in art with the shame of eroticism, they may see (or avoid seeing) its sprightly breasts, taut stomach, and large buttocks of Enchained Action only in that mode. The museum limits such visitors to this narrow viewpoint because they do not explain to them Maillol’s artful technique, conceptual artistic revolution by 1905, or unique political and socioeconomic purpose for this imposing artwork in plain view.

With an aesthetic interest established for Enchained Action—for it signals a break with the artistic past and the birth of modern sculpture in its abstraction – a question is posed: what are the political and socioeconomic purposes for this work? Its original and full title reveals a radical social implication: Torso of the Monument to Blanqui ([En] Chained Action). Abbreviated titles—and such appear at The Art Institute of Chicago, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Torso of Chained Action) and in the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris (L’Action enchaînée)—neatly avoids or even voids the sculpture’s original radical social message. Maillol’s Enchained Action is dedicated it to the French socialist revolutionary Louis Auguste Blanqui (1805-1881).

In 1905 Maillol’s Enchained Action was a public monument honoring the centenary of Blanqui’s birth and consolidation of the French socialist movement that same year into the Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO), a single leftist political party that was replaced by the current Socialist Party (PS) in 1969. Given this background a visitor may simply stare at or bypass the torso but perhaps for reasons of politics rather than eroticism. The title omission—first promoted by André Malraux in 1964 for the Tuileries’ copy—does disservice to Maillol’s accomplishment and its full title should be restored. The Metropolitan has an incomplete title but on thee label includes information on Blanqui and clearly states their version was cast in 1929. The Art Institute of Chicago’s casting date for the torso is obscure. For a better appreciation of the artwork, familiarity with its social and political historical context is important to locate the intended nature of the energy expressed in it. Torso of the Monument to Blanqui ([En] Chained Action) is a figure study of a strident naked female torso and an expression of radical politics in France at the turn of the last century.

By 1905 Maillol’s new sculptural work attracted important collectors. Rodin introduced Maillol that year to Count Kessler at the Paris gallery of Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) and to other progressive writers, art critics, and painters. Maillol’s work was a new art form for a new century. It was in 1905 that Paris friends, among them Anatole France (1844-1924), Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), Gustave Geffroy (1855-1926), Jean Jaurès (1859-1914) and Octave Mirbeau, approached Maillol to persuade the avant-garde artist to accept a commission for the politically sectarian Blanqui monument. It would be a tribute très moderne to a fierce socialist revolutionary but and the entire Blanqui family tradition which had voted to guillotine Louis XVI in the French Revolution and plotted against each ruling regime in France afterwards. Immense confidence was placed in Maillol by these bold turn-of-the-century intelligentsia and by the artist himself who came from a generation that came to believe they were the torchbearers of a new art.

In France public opinion was frequently divided on art matters. When Rodin agreed to Maillol’s commission—he wanted Camille Claudel to do it, but she had become seriously psychotic by 1905—the older sculptor admired and purchased Maillol’s new sculpture—in addition to experiencing his own deep familiarity with the vagaries of creating public monuments. Committee members, by and large left-wing sympathizers, made a favorable impression on Maillol who agreed to do the work. On July 10, 1905, Maillol promised Georges Clemenceau, “I’ll make you a nice big woman’s ass and I’ll call it Liberty in Chains.”5 After that, Maillol’s new sculpture—a symbolic monument to a political revolutionary erected in October 1908 under protest of town leaders on the main square of Blanqui’s native village of Puget-Théniers in the south of France—became the subject of unending intense scrutiny. How to respond to a large and powerful standing figure, tense and in motion where human struggling is borne to the edge of absorbing mute serenity by restraint of chains symbolizing Blanqui’s thirty years in jails by successive French governments?6 In the first ten days of working on the new commission, Maillol made three small sketches and two maquettes of an armless torso followed by other preliminary work. He finished a final clay version in 1905 whose contemplative intimacy reflected socialist Jean Jaurès’s agenda for political life: “We are inclined to neglect the search for the real meaning of life, to ignore the real goals—serenity of the spirit and sublimity of the heart … To reach them—that is the revolution.”7 Sixty-five-year-old Rodin whose critical judgment of the new sculpture which undertook to streamline art forms to the point of austerity against Rodin’s “monstrous subjects, filled with pathos” remarked tersely on Enchained Action.8 Although Maillol saw this public monument as more reliant than ever on Rodin’s concepts, M. Rodin after seeing it was reported to ambiguously mutter: “It needs looking at again.”9

It may be better to judge Enchained Action inside its historical moment. Former Metropolitan curator Preston Remington (1897-1958) praised his museum’s copy of the torso calling it “splendid” and “impeccable” in its observation of the human form. Yet he concludes that it is “essentially typical” of the sculptor for it “transcends the realm of visual reality.”10 Enchained Action displays none of the delicacy, awkwardness, luminosity, or calm of the artist’s earlier sculptures and predates major developments in Maillol’s oeuvre after 1909 which differs extensively from that of Enchained Action11 and for which is based much of the artist’s legacy, even by 1929 when Remington is writing. Is it fair to identify Enchained Action as “essentially typical” even as it sublimates form? Viewed in 1905—a watershed year for modern art, including an exhibition of Henri-Matisse’s first Fauvist canvases at the Salon des Indépendents and at the Salon d’Automne—Enchained Action became that year Maillol’s largest sculptural statement to date. The commission, while relying on Rodin’s concepts in its depiction of strenuous physical activity—a quality Preston Remington recognized as “exceptional” in the torso and yet as a critical judgment ambiguous as to whether it refers to Maillol’s reliance on Rodin—afforded Maillol further confidence to execute his monumental art after 1905 for which today he is famous. While for Mr. Remington the representative quality of Enchained Action was what he sought for a museum collection, its exceptional qualities in values that are literally not “essentially typical” for the sculptor.

The complete final figure of Monument to Blanqui([En] Chained Action)—and not only the torso that is displayed on the Grand Staircase of The Art Institute of Chicago—depicts a mighty and heroic woman struggling to free herself from chains binding her hands from behind. Both of these “complete” versions are in Paris and found in the Jardin des Tuileries and in the Musée Cognacq-Jay. Maillol’s later studies for Enchained Action commenced without its head and legs that expressed a heightened anatomical intensity in place of Rodin-like strife.12 Chicago and New York each have a bronze replica of the torso. The Tate Britain has one in lead. Following the Great War, Maillol’s Monument to Blanqui ([En] Chained Action) standing for 14 years in Puget-Théniers’ town square was taken down in 1922 so to erect a monument aux morts. During World War II fearing that the extant original sculpture would be melted down for Nazi bullets, Henri Matisse purchased it from Puget-Théniers and gave it to the city of Nice. The original bronze was saved and now stands in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris.13

NOTES

- Dynamism not anywhere else in his oeuvre – “Maillol/Derré,” Sidney Geist, Art Journal, v.36, n.1 (Autumn 1976), p.14.

- Modeled in 1905 in France – http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/196526; abandoned Impressionist painting for sculpture – A Concise History of Sculpture, Herbert Read, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1966, p.20; first in wood and later in bronze – Aristide Maillol, Bertrand Lorquin, Skira, 2002, p.33; female body central theme – Lorquin, p. 36; Maillol’s early characteristic perfection of form -Lorquin, p. 38; first admirers – see http://www.galerie-malaquais.com/MAILLOL-Aristide-DesktopDefault.aspx?tabid=45&artistid=93646-retrieved July 21, 2016.

- Wife posed – http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.artic.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053235?q=maillol&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit – retrieved Sept 9, 2015; heir of Rodin – “Maillol/Derré,” Sidney Geist, Art Journal, v.36, n.1 (Autumn 1976), p.14.

- Development of Maillol’s early sculpture-see Lorquin, pp. 30-41; purchased from Pierre Matisse in 1955 – http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/82594?search_no=6&index=12.-retrieved July 21, 2016.

- In 1964-65, 18 large bronzes were placed in the Jardins du Carrousel, Paris, owing to André Malraux and Dina Vierny, Maillol’s last model-http://www.sculpturenature.com/en/maillol-at-the-jardin-tuileries/ – retrieved July 26, 2016; Metropolitan copy cast in 1929 –http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/196526; AIC cast date obscure- http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/82594?search_no=6&index=12 – retrieved September 8, 2015; Maillol meets Count Kessler – http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/204794-retrieved May 25, 2016; torchbearers – Rodin: The Shape of Genius, Ruth Butler, Yale University Press, 1993, p.284; Rodin admired Maillol’s new sculpture- Lorquin, p.52; Rodin wanted Camille Claudel for commission– Lorquin, p. 55; “make you a nice big woman’s ass…”- quoted in Lorquin, p 56.

- Under protest by town leaders – http://www.oxfordartonline.com.proxy.artic.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053235?q=maillol&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit – retrieved September 9, 2015; Blanqui’s thirty years in jails – Clemenceau and Les Artistes Modernes, du 8 décembre 2013 au 2 mars 2014. HISTORIAL DE LA VENDÉE, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne.

- Sketches, maquettes, final version – Lorquin, p. 57-58.; Jaurès quoted in Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870-1920, James T. Kloppenberg, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1986, p. 297.

- monstrous subjects, filled with pathos – see http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/events/exhibitions/in-the-musee-dorsay/exhibitions-in-the-musee-dorsay-more/article/oublier-rodin-20468.html?S=&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=649&cHash=24aea49762&print=1&no_cache=1&, retrieved May 24, 2016.

- Rodin quoted in Lorquin, p.59.

- “A Newly Acquired Sculpture by Maillol,” Preston Remington, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 11, Part 1 (Nov., 1929), pp. 280-283.

- Such works as Night (1909), Flora and Summer (1911), Ile de France (1910–25), Venus (1918–28), Nymphs of the Meadow (1930–37), Memorial to Debussy (marble, 1930–33; Saint-Germain-en-Laye) and Harmony (1944) which are composed, harmonious, and monumental nude female figures often labeled “silent” by critics.

- Enchained Action was first modeled with arms. The story of how the first limbless final version came about involving Henri Matisse – see Lorquin, p.58.

- taken down to erect a monument aux morts – http://www.commune1871.org/?L-action-enchainee-hommage-a – retrieved September 9, 2015; purchased by Henri Matisse for Nice – Lorquin, p. 59.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2016.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 7/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 11/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 7/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2016.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 7/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 11/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 5/2016.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 7/2015.

In situ: Aristide Maillol’s Enchained Action. The torso is cast in bronze and created in France in 1905. It sits on the landing of the Grand Staircase (main entrance) of The Art Institute of Chicago.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 8/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015.

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015. 624kb 35%

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015. 5.66 mb

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015. 6.70 mb

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015. 4.88 mb

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015. 668kb 30%

47 1/2 × 28 × 21 in. (121.2 × 71 × 53.3 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. 9/2015 30%

Photographs and text: