FEATURE image: Sir Georg Solti conducting the CSO in Orchestra Hall in November 1971.

By John P. Walsh

PART I: Fritz Reiner, Jean Martinon, & Georg Solti.

In 2013 just ahead of Game Four of the Stanley Cup Finals the principal conductor and music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra dressed up in a Chicago Blackhawk’s sweater to conduct his orchestral version of their pep rally song.1 Riccardo Muti (Italian, born 1941) has worn many hats as opera and classical music conductor in a forty-year career but perhaps none with such hometown flair.

In the decades before his 2010 CSO appointment Riccardo Muti appeared to have had a knack for getting into all sorts of fine arts trouble – his resignation as music director from La Scala in summer 2005 is recent although early in his career Muti walked away from productions in Florence, Milan, and Paris because of irreconcilable differences over artistic questions. Despite these encounters, Muti continues to be one of today’s celebrated Mozart and Verdi specialists while unconventionally asserting his prestige by mounting major productions of lesser known composers. From his earliest days as principal conductor of the opera festival Maggio Musicale Fiorentino in 1968 to his appointment as chief conductor of the London Philharmonia in 1972 – both posts held into the early 1980s – as well as a longstanding association with the Salzburg Festival starting in 1971, Muti is only recently being acclaimed in America for what he has long been famous for in Europe – as a first order musical firebrand who makes opera scores spring to vivid life.2

When Riccardo Muti was made music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1980 – a prestigious post with an American orchestra which had had only two previous music directors since 1912 (namely, Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy) – Muti almost immediately stepped into the annals of controversy as a conductor in America. Classical music lovers bred on the Philadelphia Orchestra’s broad, brilliant live and recorded performances under Stokowski and Ormandy found a nemesis in Muti. Verging on his 40s, the new conductor’s ideas for this venerable orchestra with a traditionally lush and enveloping string sound were received by Philadelphia audiences with dismay. It seemed that Muti strictly observed notated musical scores and shaped distinctive interpretations from them which altered a 75-year-old sound brand. Still touting its “distinctive sound”3 today as well as other past glories, the Philadelphia Orchestra under the 44-year reign of Eugene Ormandy (1936–1980) earned 3 Gold records and 2 Grammy Awards.4 In 2014, more than 20 years after Muti’s resignation from Philadelphia, critics continue to weigh in on his enduring influence. One hears the heaving sigh of relief that Muti revolutionized less than they feared.5 Musical idealism remains Muti’s calling card coming into Chicago. Do his efforts at parceling annotated music merit negative criticism? The “very clean sound” which CSO musical director Fritz Reiner (1953-1963) brought to Chicago at a time when the orchestra was looking for stable leadership is praised; the “lean sound” which Muti brought to Philadelphia following 70 years of stable leadership produced misgivings.6 At the October 3, 2014 CSO matinée performance of Polish-themed music (Panufnik, Stravinsky, and Tchaikovsky’s Third Symphony) it is evident that Chicago’s premier group of players is subjected to a similar set of permuted articulations under Muti’s command. Yet these CSO musicians are mindful of their musical worth and perform at a high level whoever appears on the podium responding to what is asked of them.

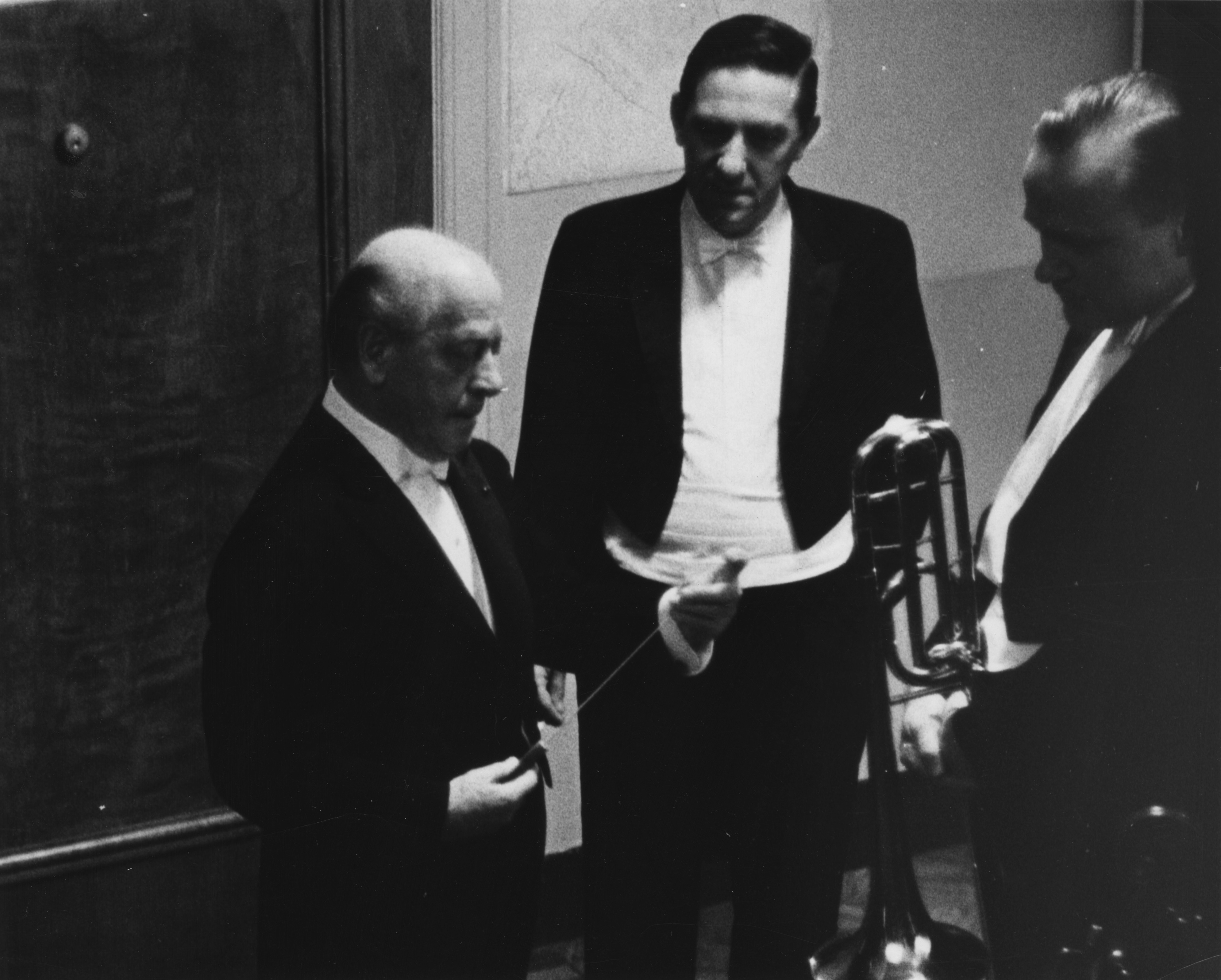

Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra Eugene Ormandy (Hungary, 1899-1985) with orchestra members in the 1960s.

Riccardo Muti (Italy, born 1941) rehearsing the Philadelphia Orchestra for his 1972 guest conductor debut with the ensemble.

Under music director Fritz Reiner the CSO’s celebrated brass section was born; later, Sir Georg Solti (1969-1991) gave it luster and clarity while Daniel Barenboim (1991-2006) added richness and depth. What is Muti doing?7 Since its founding in 1891 Riccardo Muti is the CSO’s tenth music director. Each of his predecessors had their own style but not all had the same impact or influence on the orchestra which harbors its own strong personality.8 I began my CSO concert subscription when today’s Symphony Center was Orchestra Hall and Sir Georg Solti was its music director. Like most everyone else in Chicago I was in awe of Solti. By 1985 he had with the CSO and chorus won 7 Grammy Awards for a succession of Mahler symphonic recordings plus 15 more Grammys for his Verdi, Puccini, Schoenberg, Berlioz, Mozart, Haydn, Bruckner, and Brahms. Over the next six years when I was regularly in the Hall Solti’s CSO won another 6 Grammy Awards – for his Liszt, Beethoven, Bartók, Wagner, Bach and Richard Strauss. Solti’s accomplishment in this area is wonderfully mind boggling.9 Both music director Fritz Reiner and Jean Martinon (1963-1968) wished to heighten the orchestra’s national and international profile by recordings and tours but it was maestro Solti who fulfilled and then surpassed these earlier objectives. When Solti finally left his post as music director in 1991 after 22 years at its helm he had the legacy of having established Chicago as one of the very best orchestras in the world.

Fritz Reiner (Hungary, 1888-1963) was the sixth music director of the CSO from 1953 to 1963. Russian composer Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) said that Reiner “made the Chicago Symphony into the most precise and flexible orchestra in the world.”

The CSO’s seventh music director (1963-1968) was talented composer Jean Martinon (French, 1910-1976). Never gaining the complete acceptance of orchestra members, Martinon improved the musicians’ work conditions and introduced the CSO to a new repertoire of French and contemporary classical music.

While music director in the early 1960s at Covent Garden Georg Solti (Hungary, 1912-1997) was known as “the screaming skull” for his outbursts in rehearsals.

As music director at Covent Garden for ten years starting in 1961 Solti generated a reputation for being “the screaming skull”10 because of his intense and at times bruising style. But musicians not much later in Chicago saw a different and more complex man. Solti did not bait or act harshly toward them as Reiner had done in the mode of Arturo Toscanini (Italy, 1867-1957). Reiner, in the first hour of the first rehearsal as music director, fired one of the musicians. He worked constantly after that to instill fear into his orchestra. He insisted on being called “Dr. Reiner” and inflicted cruel verbal tests onto his men to test, to his mind, their character. While believed to be utterly lacking in ready wit or sensitivity as sometimes displayed by the combustible Reiner, Solti was seen by his musicians to turn inwards into a private world.11 Unlike Leonard Bernstein, Solti could appear fashion challenged – he showed up at rehearsal in baggy pants and a simple coat thrown over a rumpled shirt. Nor did Solti drive a flashy sports car à la von Karajan or act podium showman like Stokowski. While Martinon and Solti were “late starters” to music, a 53-year-old Martinon came to the orchestra fully formed while 57-year-old Solti continued an intense drive to advance.12

The 1970s underway, Solti proved to be not the terror in rehearsal Reiner had been nor seeking anyone’s approval like Martinon. And while Solti was accessible and sometimes sought to be an intermediary to certain first-rank players’ intramural conflicts, he remained markedly tense. Solti did admit to “gentle bullying”13 in Chicago but only to get his way with the music. Respect for the CSO is high among its music directors while at Covent Garden Solti admiited he had been “a narrow-minded little dictator.”14 Under Solti’s leadership the CSO’s technical brilliance produced clear, lustrous, and notably loud sound – known as “Der Solti-Klang.” With Solti the CSO’s 1970 appearance at Carnegie Hall was a rousing success and for its first European tour in 1971 the orchestra basked in stellar reviews. In six weeks they played in Scotland, Belgium, Finland, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Italy, France and England. By 1972 the CSO won its first Grammy Awards under Solti for Mahler Symphonies 7 and 8, whose music was first suggested to Solti to conduct by Theodor Adorno. Sir Georg Solti and Chicago made for a winning team and the city shared in its glory.15

Louis Sudler (1903-1992) president of the Orchestral Association from 1966 to 1971, chairman from 1971 to 1977 and chairman emeritus from 1977 until 1992 announces that Georg Solti will become the CSO’s eighth music director beginning with the 1969-70 season.

Sir Georg Solti conducting the CSO in Orchestra Hall for the three-act opera (third act unfinished) “Moses and Aaron” by Arnold Schoenberg (Austrian, 1874-1951) on November 13, 1971.

Ticker tape parade turns north onto LaSalle Street in Chicago’s downtown financial district following the CSO musicians return from their autumn 1971 European concert tour. It was first such international event for the orchestra in its history.

In performance Solti’s large conducting gestures could appear stiff and stylized – one more aspect of the Toscanini temperament he dismissed. As Solti espoused Toscanini’s belief that music cannot be chopped up and must relax and flow Solti did not follow Toscanini’s lead – as Riccardo Muti, a Toscanini admirer, does not- to forego the written musical score on the conductor’s podium during a concert. If Muti’s reason is to read and interpret a score’s annotations, Solti’s was a psychological one. Like Toscanini Solti committed the music to memory but kept the annotated score ever-present to serve as an insurance policy for musicians, especially singers, who Solti believed needed reassurance that the conductor had everything under control during a performance. Despite this careful preparation, a recurring criticism of Solti’s work is that it “lack[ed] refinement…finesse and, above all, attention to detail.” 16 For the keen musical mind of Daniel Barenboim who brought neither Solti’s or Muti’s purpose to the podium he nearly always conducted like Toscanini with no score.

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) demonstrating conducting gestures for a crescendo.

Sir Georg Solti in rehearsal with mezzo-soprano Josephine Veasey (British, born 1930) in Covent Garden, 1966.

Daniel Barenboim in a typical conducting stance at the Veranos de la Villa Festival in Madrid.

Riccardo Muti conducts the CSO in an October 4, 2012 performance at Carnegie Hall.

When Sir Georg Solti died suddenly in September 1997 there was the critical reaction linking him to the passing of an era – an erstwhile time of “old school toughness” when a conductor was a “super-hero” who did not negotiate musical interpretation but demanded it and never shared credit or fame with any musician. But this, of course, is largely myth. The era of “democratic playing” which is criticized as today’s musical model – that is, one of dialogue and partnership between conductor and ensemble – is in fact something that started in the United States and elsewhere around 1960 when Solti was embarking on the next four decades of his best work.17 In what ways is Muti’s directorship affecting “the Chicago sound”? How is this new and highly experienced, talented and forceful conductor – conducting Stravinsky’s “The Firebird” on October 3, 2014 Muti jabbed the air like a boxer – an old Solti gesture – changing this vital orchestra? CSO’s future lies in Muti’s head, heart and hands and while players are incredibly talented (no orchestra plays Strauss and Mahler better) Muti keeps them on a tight leash. How do the musicians respond to his direction? Results from such control and semiotic interpolation of a composer’s intention in the score should be the grounds on which the public will judge Riccardo Muti over time. The CSO strives to play to its Chicago audience, not to one in Asia or Europe, and so the case for Muti’s rise or fall will essentially be local.

NEXT: Daniel Barenboim.

Footnotes:

1 Huff post Chicago, “Chicago Symphony Orchestra Plays ‘Chelsea Dagger’ In A Classy Show Of Support For The Hawks,” 06/20/2013. Retrieved October 2014.

2 irreconcilable differences – http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Riccardo_Muti.aspx. Retrieved October 2014; makes opera scores spring to vivid life – Peter G. Davis, “The Purist,” Opera News, October 2014, vol. 79, no. 4. Retrieved October 2014.

3 https://www.philorch.org/history#/ and http://www.spac.org/events/orchestra. Retrieved October 2014.

4 3 Gold records; 2 Grammy Awards – Townsend, Dorothy (13 March 1985). “Philadelphia Orchestra’s Eugene Ormandy, 85, Dies”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2014. See also http://www.grammy.com.

5James R. Oestreich, “The Big Five Orchestras No Longer Add Up,” New York Times, June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 2014.

6 William Barry Furlong, Season With Solti: A Year in the Life of the Chicago Symphony, Macmillan Publishing Co., 1974, p. 52.

7 whatever is asked of them – Donald Peck, The Right Place, the Right Time: Tales of Chicago Symphony Days, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2007, p. 6; brass born under Reiner – Oestreich; luster and clarity – Furlong, p. 84; richness and depth – Emanuel Ax, http://www.gramophone.co.uk/editorial/the-world%E2%80%99s-greatest-orchestras.

8Furlong, p. 62.

9 See http://www.grammy.com.

10 Furlong, p. 86.

11 insisted on being called “Dr. Reiner” – Peck, p. 2; private world – Furlong, p. 52.

12 flashy sports car – Furlong, p.79; podium showman – Furlong, p.81; “late starters” – Furlong, pp. 58 and 87; fully formed – Furlong, p.60; intensely driven – Furlong, p. 83, 141.

13 Furlong, p.86.

14 Furlong, p. 88.

15 technical brilliance – Furlong p.81; “Der Solti-Klang” – Furlong, p. 85; “stellar reviews” – Review of ”The Chicago Symphony Orchestra by Robert M. Lightfoot; Thomas Willis,” by M. L. M., Music Educators Journal, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Dec., 1974), pp. 87-88; European itinerary – http://csoarchives.wordpress.com/2012/08/18/solti-26-1971-tour-to-europe/. Retrieved October 2014; suggested to Solti by Theodor Adorno – Sir Georg Solti, Memoirs, Knopf, NY 1997, p. 100.

16 On Solti’s and Toscanini’s relationship – see Furlong, pp. 86; 93-94, 141; for quote “lack[ed] refinement…” – Furlong, p. 85. Solti first worked with Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) at the Salzburg Festival in 1936 and was invited by him to New York in 1939.

17 Old school toughness – Review of “The Right Place, the Right Time! Tales of the Chicago Symphony Days by Donald Peck,” by Lauren Baker Murray, Music Educators Journal, Vol. 95, No. 1 (Sep., 2008), pp. 21-22; “super hero” – “Editorial: Leading from the Front,” The Musical Times, Vol. 138, No. 1857 (Nov., 1997), p. 3; dialogue and partnership… started in…1960 – Furlong, p.110.