FEATURE image: “Cary Grant” by classic film scans is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

By John P. Walsh

Cary Grant made exactly 72 feature films between 1932 and 1966. These ranged from classics of the genre that had the debonair English-American actor with boundless energy and superb timing tangle with Thrillers—Suspicion (1941), To Catch a Thief (1955), North by Northwest (1959)—and Comedies—Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940)— and Romances—Notorious (1946), An Affair to Remember (1957) – and much, much more.

In his 34-year Hollywood career Grant made his final films in the 1960’s – That Touch of Mink (1962), Charade (1963), Father Goose (1964), and Walk, Don’t Run (1966) – and they became some of his best work. Soon afterwards, Grant decided to retire at what was both a career and personal high note. In June 1965 the 61-year-old Grant married actress Dyan Cannon, 33 years his junior, and had his first child with her who was born in late February 1966. It was Dyan Cannon’s first marriage; Grant’s fourth. They divorced in 1968. After an acting career spanning four decades—Grant’s film debut was in 1932 for Paramount Pictures’ This is the Night, a comedy—Grant chose to say good-bye to the silver screen at 62 years old. In 1970 he received his sole Oscar, an honorary one for which he was pleased and humbled as his acceptance speech before the Academy and the whole world shows. It was Hollywood’s Golden Age, and in that time, Cary Grant had become a household name synonymous with suavity, comedy, drama, romance, and his perpetually tanned-and-pressed good looks.

“Ours is a collaborative medium—we all need each other,” Cary Grant said as he accepted his honorary Oscar from presenter and friend Frank Sinatra at the 42nd Annual Academy Awards ceremony on April 7, 1970 at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, California.

Grant’s final film came in 1966 with the summer release of the comedy, Walk, Don’t Run. It was one more film made by one of Grant’s newly-formed production companies and distributed by Columbia Pictures. Not coincidentally, in February of that same year, Grant became a father for the first time. Grant now looked to give his baby daughter, Jennifer—who Grant called his “best production”—the best of his time and attention. Grant opined: “My life changed the day Jennifer was born. I’ve come to think that the reason we’re put on this earth is to procreate. To leave something behind. Not films, because you know that I don’t think my films will last very long once I’m gone. But another human being. That’s what’s important.”

Cary Grant and wife Dyan Cannon with their baby daughter who was born on February 26, 1966.

Grant starting wooing Dyan Cannon in 1962. Within a three-year whirlwind courtship, as well as becoming eventually pregnant with Grant’s baby, a 28-year-old Dyan Cannon in 1965 sought once more a marriage proposal from one of cinema’s best, perhaps the best, and most important actors. But, once married, Dyan Cannon soon discovered that their marital relationship was more polite and frosty than she had expected to face with Hollywood’s quintessential leading man. On March 20, 1968, less than three years after tying the knot in a secret wedding ceremony in Las Vegas, Nevada, followed by flying to England in a private jet supplied by Grant’s longtime friend, magnate Howard Hughes, Cannon sought and was granted a divorce. As Cary Grant’s former wife and mother of his only child, Cannon did receive alimony from Grant to raise their daughter but the up-and-coming actress had to sort things out more completely after their break-up. Theirs had been a love affair with many memorable romantic moments. But Grant’s earlier confidence to Cannon when they were dating could have been seen as a warning of sorts if things happened to get more serious. “I don’t know what it is, but something happens to love when you formalize it,” Grant told her. “It cuts off the oxygen.”

Grant appears in character as an angel named Dudley in this promotional photograph for the 1947 fantasy romance film, The Bishop’s Wife. By seductively playing a certain song on the harp, Dudley convinces a rich woman to support the bishop’s cathedral building project. In real life, Grant was an ardent piano player.

When Grant asked to meet Dyan, she assumed it was for an acting part. Grant began his romance with then 25-year-old Dyan Cannon in 1962. By fall of 1962 the couple flew from California to New York where Cannon began rehearsing for The Fun Couple, a Broadway comedy play starring Jane Fonda and directed by Andreas Voutsinas. Grant meanwhile worked with film director Stanley Donen on Charade, an upcoming romantic comedy, pseudo-Hitchcock mystery thriller that Grant would co-star in with Audrey Hepburn. Hepburn had been filming another romantic comedy, Paris When it Sizzles, with William Holden.

Promotional poster for Stanley Donen’s Hitchcockian suspense thriller, Charade. The hit 1963 film was made in Paris in 1962 and 1963 and released at Christmas 1963. It starred Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn.

The Main Title for Charade with its punchy animated titles by Maurice Binder (1918-1991) was composed by Henry Mancini (1924-1994). At 39 years old Mancini was an Academy Award-winning composer — Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961 and Days of Wine and Roses in 1962. Charade would begin a number of successful collaborations for Mancini with Stanley Donen in the 1960’s, including Arabesque in 1966 starring Sophia Loren and Gregory Peck and Two For the Road in 1967 with Audrey Hepburn and Albert Finney.

Henry Mancini, c. 1970. The Main Theme from Charade was the first of a number of successful film score collaborations Mancini had with director Stanley Donen in the 1960’s.

On the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart a slightly longer vocal version of Charade reached no. 36 and was one of two top-40 pop hits for Mancini in 1963. It peaked at no. 15 on the Adult Contemporary chart. Charade produced one of Mancini’s eighteen Academy Awards nominations (he won four) for Best Original Song. The Oscar that year went to Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn for “Call Me Irresponsible” from Papa’s Delicate Condition, a comedy starring Jackie Gleason and Glynis Johns.

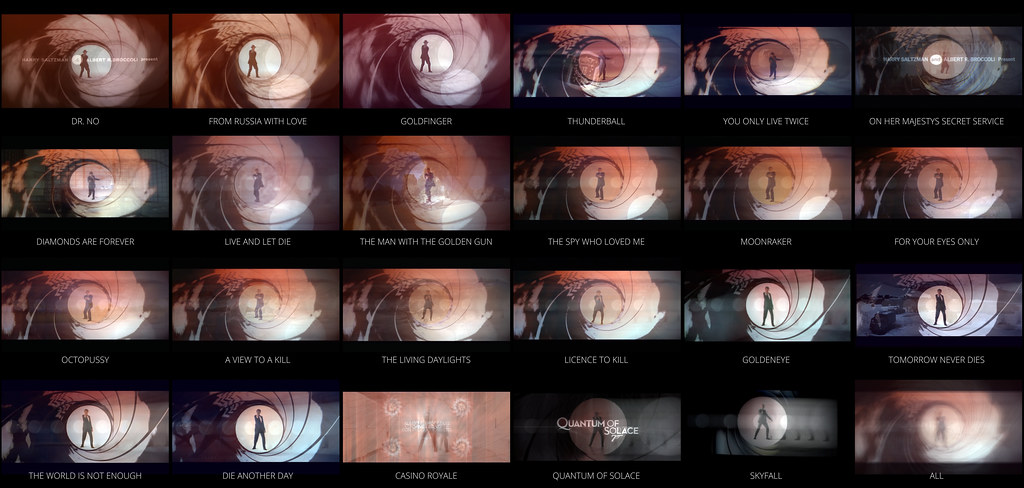

Maurice Binder did film title designs for dozens of films but is particularly known for ones he did for Stanley Donen such as Charade, as well as Indiscreet in 1958, The Grass Is Greener in 1960, and Bedazzled in 1967. Maurice Binder is also famous for 16 James Bond film titles he designed starting with the first Bond film, Dr. No, in 1962. In 1991 Binder explained the genesis of his main titles for Bond: “That was something I did in a hurry, because I had to get to a meeting with the producers in twenty minutes. I just happened to have little white, price tag stickers and I thought I’d use them as gun shots across the screen. We’d have James Bond walk through fire, at which point blood comes down onscreen. That was about a twenty-minute storyboard I did, and they said, this looks great!”

Bond Films Openings. Maurice Binder created the series’ first “Gun Barrel Sequence” for Dr. No in 1962.

Charade’s animated Main Title and music follows a wide screen shot of a quiet pre-dawn countryside in Europe as a speeding train eventually approaches and screeches past. A body is dumped out of the moving train, plunges down the ravine and stops in a ditch, the camera providing a close-up of the dead victim’s face. Colorful animation follows of pinwheels as the relentless wood-block-driven music heighten tension for what will be two charming lovers caught in a mysterious web of criminals after money.

Stills montage of Maurice Binder’s Main Title for Charade that accompanies Henry Mancini’s music.

Grant reluctantly left Cannon and the comforts of his suite at the Plaza in New York to make his way to Paris to shoot Charade (Hepburn’s home was near Paris). Walking along the left bank of the River Seine near Notre Dame is the Pont au Double bridge, just below the Quai de Montebello. During the filming of Charade, Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn walk along the riverbank below this bridge as they discuss who the killer is. Just outside of Parc Monceau is the Musée Cernuschi on the Avenue Velasquez. The museum is featured in Charade, where it is used as Reggie’s apartment which she finds ransacked after returning from a holiday ski trip. Located near the Louvre is the Palais Royal which was originally the residence of Cardinal Richelieu, and later the property of the King of France housing apartments, offices, shops and restaurants. The Palais Royal appears in Charade in its final scenes when the real Carson Dyle is revealed and shooting begins.

Shooting scenes for Charade involved many locations in Paris.

When Dyan Cannon had her first holiday break from Broadway rehearsals at Christmas, she hopped on a flight to Paris. Arriving on Boxer Day in 1962, Grant and Cannon spent the next several days together in his hotel. On New Year’s Eve, Grant and Cannon were the special guests of Audrey Hepburn and her husband Mel Ferrer at their castle. There was a sumptuous dinner and many flights of crisp and creamy French champagne. Cannon flew back to the States on January 2, 1963, after a most pleasant holiday. She resumed her theater work in New York City while Grant and friends stayed on in Paris to continue filming Charade.

Cary Grant, making his 70th film, was reluctant to leave the U.S. for Paris for the several months in late 1962 and early 1963 it took to film Charade. It premiered at Radio City Music Hall in New York City on Christmas Day 1963.

Radio City Music Hall in 2008.

The film Charade is well-known for its Hitchcock-style inspiration and screenplay by the original story’s author Peter Stone (1930-2003). From Stone’s 1961 short story, The Unsuspecting Wife, the film Charade offers witty lines and a head-knocking, heart-pounding whodunit. In Charade, Regina “Reggie” Lampert (Hepburn) is on winter holiday in the French Alps. Returning to her home in Paris, she is shocked to find that it has been ransacked of everything of value. The mysterious victim in the Main Title and the mysterious man Reggie just met on holiday in Grenoble– Peter Joshua, alias Alexander Dyle, alias Adam Canfield, alias Brian Cruikshank (Cary Grant) –merge into her life to help her solve the mystery of why these crimes have occurred and what they mean. Charade is about hidden money, spies and larcenists, double-crossing and being on the run. Besides that, it’s a love story. Charade was one of the last of a long line of suspense-screwball comedy films –a staple Hollywood film genre since the 1930’s–that faded out during the tumultuous 1960’s and not to reappear until the 1980’s.

Charade opened on December 25, 1963 at Radio City Music Hall. The film made six million dollars while the reviews, though mixed, were mostly positive. Critics did remark on the age difference between the romantic leads –a 59-year-old Cary Grant and 34-year-old Audrey Hepburn. By early 1964 the perfectly suave and likeable leading man for over 30 years was beginning to think about retirement. But there were still some things he hoped to accomplish first.

Charade in the rear view mirror, Grant came home just as Cannon became mostly absent. Throughout 1964 and much of 1965 Cannon had done no film work yet but continued her theater career as she was touring the country in the musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. Looking for something to do with his time, Grant formed a production company and made Father Goose.

Photographs above: Cary Grant in Operation Petticoat.

Grant’s character, Walter Eckland, played against Grant’s film type. Ecklund was a bedraggled loner in the South Pacific during World War II who reluctantly takes under his protection an unmarried French school teacher (Leslie Caron) and her seven grade school students. They were suddenly made refugees from the war during a Japanese bombing raid. The heart-warming Father Goose was a mega-hit at its release during Christmas 1964 and made millions of dollars. Receipts, however, were significantly less than in each of Grant’s three previous films — Operation Petticoat in 1959 with Tony Curtis, That Touch of Mink in 1962 with Doris Day, and Charade. Despite a lot of pre-Oscar buzz, Grant wasn’t even nominated for his performance. It was one more disappointment for Grant as he worked to possibly be given an Academy Award before he might retire.

Cary Grant and Doris Day in the hit romantic comedy, That Touch of Mink. Grant was dismayed that his 1964 romantic comedy adventure film Father Goose made less money than Charade and almost $6 million less than That Touch of Mink in 1962 and Operation Petticoat in 1959 combined.

That Touch of Mink co-starred Doris Day and Cary Grant. It was the hit movie of summer of 1962 though outshined in the movie world later that year by Lawrence of Arabia and The Longest Day. The romantic-comedy is great fun—it won, in this different age, a Golden Globe award for Best Comedy Picture-—and became a popular rerun on TV for the next decade.

Cary Grant was cast as wealthy businessman Philip Shane, a role originally meant for Rock Hudson. That Touch of Mink was, above all, intended to be a Doris Day vehicle. From 1962 to 1964 Doris Day was THE top box office star in Hollywood. Her presence definitely contributed to Universal Pictures’ bottom line since That Touch of Mink was the fourth biggest money maker of that year.

Playing working girl Cathy Timberlake, the movie is basically a stylish “boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back”—and given a chance to learn his lesson, they get married. American audiences loved the concept as well as Day and Grant together on the big screen. The film was the fastest million-dollar earner of the year- and set a record at the time for the highest gross earnings in an initial theatrical release.

For Grant it was his second highest grossing film of his 30-year career, which was especially prosperous for the 58-year-old actor since he was a co-producer. Grant personally made $4 million for That Touch of Mink (around $35 million in today’s money). Three weeks after its opening, Betsy Drake, Grant’s third wife, found it an opportune time to file for divorce.

The court proceedings of the high-profile couple after more than a decade of marriage were followed intimately by the press. The settlement for Drake, who told the papers, “I was always in love with him and I still am….but…he left me long ago,” included over one million dollars in cash and a profit share in every Cary Grant film ever made up to 1962.

Meanwhile, That Touch of Mink, a film thick with early 1960’s conventional sensibilities, was nominated for 3 Academy Awards. Both Grant and Doris Day never won an Academy Award. In 1970, after Grant retired from film, he won an Honorary Academy Award. The story goes that after her exit from films, Doris Day (born Doris Kappelhoff in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1922) was offered the Honorary Oscar multiple times but always turned it down. In 1962 That Touch of Mink was nominated for Best Sound, Best Art Direction and Best Screenplay. For the first two categories Oscar went to Lawrence of Arabia and, for the third category, to Divorce Italian Style.

Newly married in June 1965 to Dyan Cannon who was expecting their baby, Grant announced he was flying to Japan to make another movie. Grant returned to California permanently just in time to drive his wife to the hospital to deliver their first child, a baby daughter, born on February 26, 1966.

In June 1965, with Father Goose and the Oscars behind him and Dyan Cannon’s national tour ended—Grant and Cannon, who was now pregnant, got married. After a secret marriage ceremony in Las Vegas and a honeymoon, their news was eventually publicized. As the excitement began to settle down, Grant informed Cannon he would be making another film—and was traveling to Japan by himself for the next many months.

Grant had formed another production company and with producer Sol C. Siegel, signed with Columbia Pictures to distribute his new film. Buying the rights to The More the Merrier, a World War II-era comedy, Grant took the role that had been nominated in the early 1940’s for an Academy Award. Grant’s 1966 remake was called Walk, Don’t Run in which he played a British industrialist, Sir William Rutland,

The music is by Quincy Jones including its main title, “Happy Feet.”

The story concerns three strangers—Sir William (Grant), American Olympic competitor Steve Davis (Jim Hutton), and a young single British expat Christine Easton (Samantha Eggar). Leading different lives they suddenly come together to share a cramped apartment in Tokyo during the busy 1964 Olympics. Grant personally selected Hutton and Eggar for their roles.

In the film, Christine, whose tiny apartment it is, would prefer a female roommate. She sublets to Sir William because he is pushy, charming and a fellow Brit in need. But he immediately sublets half of his portion to Hutton, making for three.

Comedy results from three outsized adults sharing an acutely small living space as they pursue as normally as possible their lives’ conflicting schedules. In Grant’s last film he intentionally worked it so he did not get the girl. Rather Sir William tries to get Christine, who is engaged to a boring British diplomat, to hook up with Hutton.

Walk, Don’t Run was one of Quincy Jones’s first big breaks. The 33-year-old Chicago-born Jones came to score the film after its star and Executive Producer, Cary Grant, recommended him for the job. Grant met him briefly through their mutual friend, singer Peggy Lee. From that meeting Grant felt Jones’ style would be perfect for the film and he made sure he was hired. Jones went on to enormous success as the composer of numerous film scores such as In the Heat of the Night in 1967 and The Color Purple in 1985 as well as the producer of successful pop rock recordings such as Michael Jackson’s bestselling albums, Off the Wall in 1979, Thriller in 1982, and Bad in 1987. Jones was executive producer of the 1985 global recording phenomenon, We Are The World. That collaborative recording project raised funds for victims in Ethiopia when one million people died in that country’s 1983–1985 famine. In 2013, Quincy Jones was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

After Grant returned from Asia and the baby was born, in private and public he was adament that Walk, Don’t Run—released in June 1966—was his last film. It proved to be true. Grant stated he would not make a film with his wife, Dyan Cannon, a talented actress whose career had just begun. Instead, Grant insisted Cannon should retire from acting and be a stay-at-home mother. Grant’s ideas were not welcome news to Dyan Cannon, 33 years her husband’s junior. Already in 1966 Cannon began to wonder if—following an exciting courtship and an age difference they barely mentioned—her marriage to Cary Grant was in trouble.

NOTES:

Best production— “Hollywood loses a legend”. Montreal Gazette. December 1, 1986. p. 1.

That’s what’s important— McCann, Graham (1997). Cary Grant: A Class Apart. Columbia University Press, 1998.

Cuts off the oxygen— http://worldnewsblogx.blogspot.com/2011/10/my-husband-cary-grant-force-fed-me-lsd.html

Charade film locations—https://www.wessexscene.co.uk/travel/2017/02/21/audrey-hepburn-in-paris/

Fastest million-dollar earner of the year and record for highest gross earnings in an initial theatrical release – “Million-$ Gross In 5 Weeks; ‘Mink’ A Radio City Wow”. Variety, July 18, 1962. p.1. and “B’way as Spotty as Weather; ‘Town’ Big $41,000, ‘Guns’ Only Okay $20,000, ‘Grimm’ Giant 59G, ‘Mink’ 151G, 10th” Variety, August 22, 1962. p.9.

Betsy Drake settlement – Eliot, Marc, Cary Grant A Biography, Harmony Books, NY 2004, p 337.

Last film and would not make a film with his wife— Ibid., p. 352.

Might be in trouble—Cannon, Dyan, Dear Cary: My Life with Cary Grant, 2011, p. 217 ff.

PHOTO CREDITS:

FEATURE image-Cary Grant by classic film scans is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

2-Cary Grant by classic film scans is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

3-Fair use.

4-Cary Grant by twm1340 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

5-CHARADE by Laurel L. Russwurm is marked with CC0 1.0.

6-Public domain published in a collective work i.e. periodical in the US between 1925 and 1977 and no Copyright.

7-Bond Films Openings Montage (Amalgamation) by avhell is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

8-Charade titles by Maurice Bender by Stewf is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

9-Charade_1963_Audrey_Hepburn_and_Cary_Grant public domain because it was published in the United States between 1925 and 1963 and although there may or may not have been a copyright notice, the copyright was not renewed.

10- Cary Grant, in Charade 1963 by Movie-Fan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

11- Let’s continue this little Charade by Thiophene_Guy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

12-Radio City Music Hall (2008) by jpellgen (@1179_jp) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

13-Cary Grant by classic film scans is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

14-MM008600-39 by Florida Keys–Public Libraries is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

15- Cary Grant and Doris Day by classic film scans is licensed under CC BY 2.0,

16-1947 Bristol-born Hollywood film star Cary Grant alighting from Bristol Freighter G-AGVC at Los Angeles, 13 Jan 1947. by Gary Danvers is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

17- Walk, Don’t Run poster. Fair use.

18-Fair use.

CARY GRANT HOLLYWOOD FILMOGRAPHY (1962-1966):

1962:

That Touch of Mink

Cary Grant as Philip Shayne

Directed by Delbert Mann

Released June 14, 1962

Universal Pictures

1963:

Charade

Peter Joshua / Alexander Dyle / Adam Canfield / Brian Cruikshank

Directed by Stanley Donen

Released December 5,1963

Universal Pictures

1964:

Father Goose

Walter Christopher Eckland

Directed by Ralph Nelson

Released December 10, 1964

Universal Pictures

1966:

Walk, Don’t Run

Sir William Rutland

Charles Walters

Released June 29, 1966

Columbia Pictures

*The photograph copyright may be believed to belong to the distributor of the film, Universal Pictures and Columbia Pictures, the publisher of the film or the graphic artist. The copy is of sufficient resolution for commentary and identification but lower resolution than the original photograph. Copies made from it will be of inferior quality, unsuitable as counterfeit artwork, pirate versions or for uses that would compete with the commercial purpose of the original artwork. The image is used for identification in the context of critical commentary of the work, product or service for which it serves as poster art. It makes a significant contribution to the user’s understanding of the article, which could not practically be conveyed by words alone. As this is a publicity photo (star headshot) taken to promote an actress, these have traditionally not been copyrighted. Since they are disseminated to the public, they are generally considered public domain, and therefore clearance by the studio that produced them is not necessary. (See- Eve Light Honthaner, film production expert, in The Complete Film Production Handbook, Focal Press, 2001 p. 211.) Gerald Mast, further, film industry author, in Film Study and the Copyright Law (1989) p. 87, writes: “According to the old copyright act, such production stills were not automatically copyrighted as part of the film and required separate copyrights as photographic stills. The new copyright act similarly excludes the production still from automatic copyright but gives the film’s copyright owner a five-year period in which to copyright the stills. Most studios have never bothered to copyright these stills because they were happy to see them pass into the public domain, to be used by as many people in as many publications as possible.” Kristin Thompson, committee chairperson of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies writes in the conclusion of a 1993 conference with cinema scholars and editors, that they “expressed the opinion that it is not necessary for authors to request permission to reproduce frame enlargements … [and] some trade presses that publish educational and scholarly film books also take the position that permission is not necessary for reproducing frame enlargements and publicity photographs.”(“Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills,” Kristin Thompson, Society for Cinema and Media Studies.)