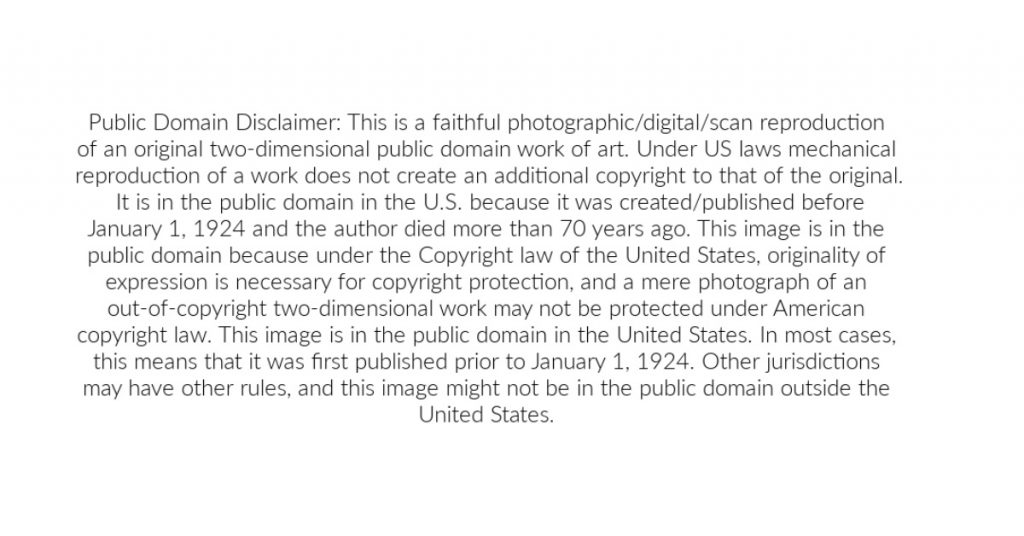

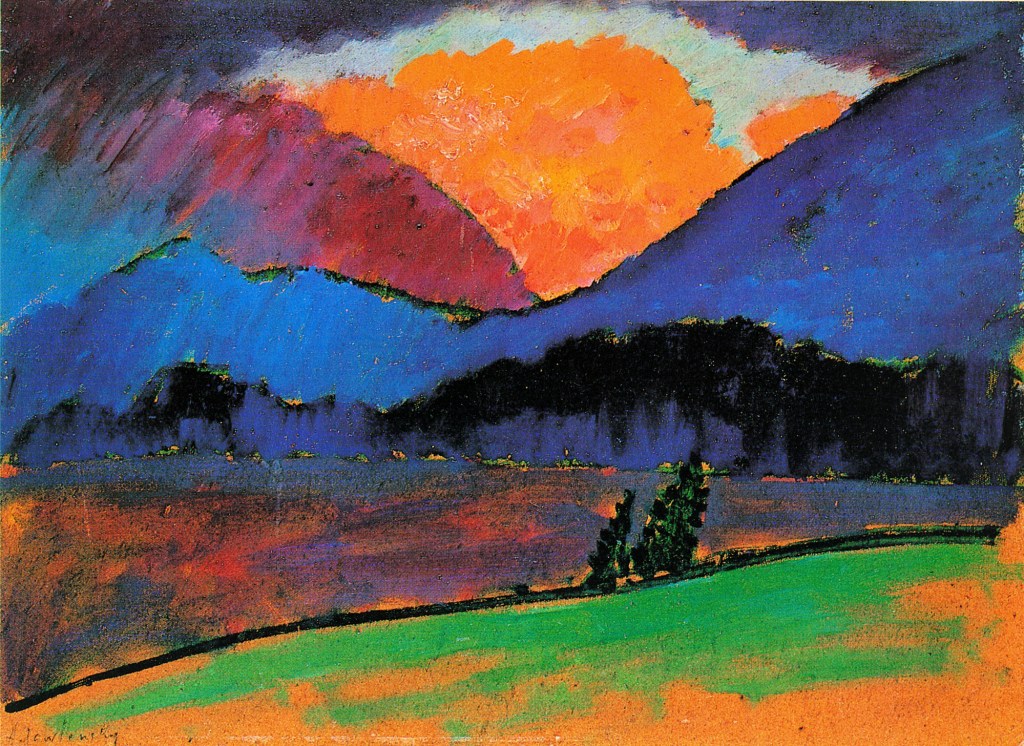

FEATURE Image: Jawlensky, Hügel (Hills), 1912, oil on hardboard, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund.

Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941), Russian-émigré German Expressionist painter.

SUMMARY:

Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941), a young Russian-émigré artist to Germany beginning in the mid 1890’s, became one of the most progressive avant-garde modernist artists of his generation. His international search—from Russia to France, England and the Low Countries, as well as his lifelong expatriate base in Munich, Germany—led him to experiment and synthesize unto German Expressionism the main currents of modern art styles before World War One. This included significant borrowings from Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Cloisonnism, Synthetism, Symbolism, and Fauvism. Jawlensky, with Russian compatriot Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and German painter Gabriele Münter (1877-1962), among several others, pursued a decade-long dialogue of their individual experimentation, particularly in the liberation of color and form, as, in part, an artistic response to a modern society increasingly saturated by industrialization and mechanization. Within the socio-economic context of a rising newly-formed German Empire before World War I, these emergent German Expressionists sought to free the object (and unto the natural world) from its objective fixity and situate it within the inner feelings and spirit of the artist. Within European modernism, Jawlensky developed a wide network of contacts and took especial inspiration from modern painters such as Édouard Manet (1832-1883), Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), and others. Jawlensky sought in modern art exhibitions and the co-founding of, and participation in, the New Munich Artist’s Association in 1909 and Der Blaue Reiter in 1911, to lead modern art towards representational expressionism and abstraction.

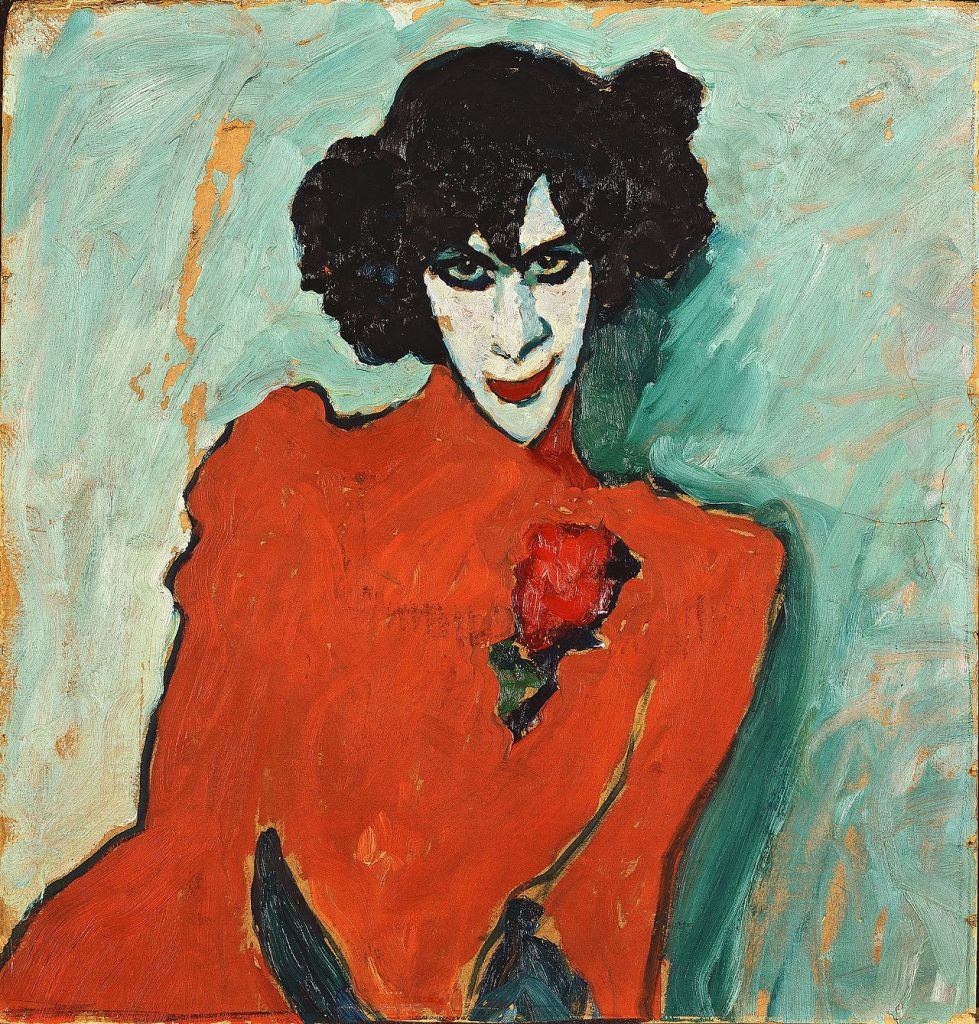

Alexei von Jawlensky, Self Portrait, 1912.

In 1871, the newly-founded German Empire fused together most of the German speaking states in Central Europe under Prussian leadership. Over the next 60 years under several different forms of government—that of Emperor Wilhelm I (1871-1888), his grandson Wilhelm II (1888-1918) and, following World I, the Weimer Republic (1918-1933) —Germany worked to create and define a political and cultural identity all its own.

In World War I (1914-1918), the recent German Empire fought to consolidate its gains but the effort failed—and Central European powers were divided up into smaller states after the war. The German Empire had risen and fallen in less than 50 years.1

Before unification in 1871, German-speaking denizens of Central Europe came from many independent and differing political units. The Kingdom of Prussia, which in 1816 annexed the Kingdom of Brandenburg, was the foremost German power alongside Austria. Long-held liberal dreams based on the French Revolution of 1789, the Napoleonic empire (defeated at Waterloo in 1815) and later mid-19th century pan-European revolutions looked to unify these diverse states into a national union based on self-determination. But these idealistic political aspirations did not reflect all the conditions and facts in these lands.

Napoleon’s invasions into Central Europe in 1806 and 1807 resulted in German state governments that were conservative and anti-constitutional monarchies. When unification came for Germany in 1871, it was not by popular uprisings or democracy. It was the diplomatic handiwork of the six-foot-three-inch Prussian prime minister, Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898).

Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898).

In 1849, Otto von Bismarck was elected to the Landtag, or Prussian parliament. Following a decade of government service, König Wilhelm of Prussia appointed Bismarck in 1862 as Minister President of Prussia and Foreign Minister. This gave Bismarck virtual absolute power.

In 1866, Bismarck started a short, decisive war with Austria. It proved Prussia was the dominant force in German territory. The Austrian war led to the Prussians with their allies annexing territories and forming the North German Confederation comprised of 22 German states. Nationalism throughout German-speaking Europe rose significantly after this military victory over Austria which had in the contest lost its dominant power position in Europe.

By 1870, German unification was both cause and effect of German nationalism. Unification was opposed by European nations, particularly France, as well as German expansion. The smaller German kingdoms reacted to the diplomatic opposition by uniting with Prussia. It was France that, since the 17th century, was viewed as the actual destabilizing force in Europe, and not a new Germany.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 which started when France was maneuvered by Bismarck to declare war on the North German Confederation, was a disastrous defeat for France. The Prussian victory allowed them to annex Alsace-Lorraine from the French and became another impetus for independent German states to join a united Germany. The German empire was founded and declared on New Year’s Day, 1871. Bismarck crowned Wilhelm as Kaiser Wilhelm I, and Bismarck became Grand Chancellor.

With Austria as an exception, Bismarck ruled the German states as the Second Reich. He brutally censored and repressed any contradictory forces to German nationalism—including the Catholic Church and the Communists and worked to mold scattered German speaking residents into one political and cultural nationality. This nationalistic vision of centralized power—and entangling alliances to support or offset it—led to the mechanized death mill of World War I. In that conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire—the so-called Central Powers—fought the Allied Powers of Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Japan and, later, the United States.

In this “Great War” the total number of military and civilian casualties on both sides was around 40 million—about 20 million deaths and 21 million wounded. Of the 20 million deaths, it included about 10 million in the military and 10 million civilians. The Allies lost almost 6 million soldiers and the Central Powers lost about 4 million.2

World War I was a dividing point in modern history which also had effects on modern art in Germany. Many young, avant-garde artists were killed in action as soldiers in the war. Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Alexei von Jawlensky (1864-1941), both Russian-émigrés, had to flee Germany, only to emerge from the general carnage years later. After the war, German architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969) believed that his work could be picked up precisely where it was left off before the war. But Gropius quickly realized that was not going to happen going forward, as if the worldwide calamity could exclude art-making in its whirlwind.

Prior to World War I, however, the German Empire experienced dynamic activity and prosperity. During Wilhelm II’s 30-year reign (1888-1918), rapid industrialization, population growth, and the growing gap between an increasingly wealthy and politically influential elite and disenchanted working class rippled throughout the empire. Berlin became Germany’s national capital and Europe’s young new city.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, c. 1901, by German painter Christian Heyden (1854-1939).

Antique map of the German Empire in 1900 showing population density.

Within this modern-state commotion, the role of art in Germany became a battle for the nation’s soul: from the pole of freedom to produce outstanding artworks in the modernist spirit to a regressive cultural heritage with proto-fascist overtones. Cultural conservatives argued for turning inward to German sources for the future direction of German art. These conservative critics dismissed French Impressionism as nonacademic, genre painting of modern life. Above all, it was foreign.

Conversely, the Berlin Secession (1898-1934) and Neue Galerie Thannhauser in Munich challenged academic and state-sponsored artwork and introduced international styles. These venues were where Germans went to see post-Impressionists such as Vincent Van Gogh and later Cubists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

By the dawn of the 20th century, what it meant to be German, and among a culturally diverse citizenry, was a 30-year experimental construct forged by Bismarck using raw power so to achieve a unified empire on the world stage. The fall of that empire and the peace that followed it, helped set the stage for the rise of Fascism leading to World War II.

Modern artists of the key artistic movements of the Wilhelmine period, particularly Expressionist art groups such as Die Brücke (“The Bridge”) in Dresden from 1905 to 1913 and Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) in Munich from 1911 to 1914 — avant-garde forms of modernist abstraction and romanticism — wanted to offset conventional social values based on German industrial materialism by using a contradictory form of self-expression based on the sensual and spiritual.

The issue of what exactly was, or would be, “German” art in the modern age were the stakes for these artists. These artists sought to unify body and soul by expressing internal qualities through exterior appearances and saw this integrated expression as their contribution to that societal and artistic endeavor.3 Progressive artists never dismissed the idea of a German art. They sought its expression in avant-garde artistic elements and forms thereby rejecting its basis on historical and cultural anecdote or nostalgia.

Published in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1900 the map of the Russian Empire is labeled in French with topography relief shown by hachures and Paris as the meridian reference. Transcontinental rail lines in Russia and extend to Paris. Jawlensky, born in western Russia in 1864 was stationed in the 1880’s as a soldier in Moscow and St. Petersburg. As a professional artist in Germany in the 1890’s and afterwards, Jawlensky returned to visit Russia including in the year this map was made. (see- https://www.mapsofthepast.com/russia-empire-kartograficheskoe-circa-1900.html

Alexei von Jawlensky, born in Torzhok in western Russia in 1864, started his career in the military. At 25 years old, in 1889, Jawlensky, stationed in Moscow, requested a transfer to St. Petersburg to study painting at the Academy of Arts. In St. Petersburg, Jawlensky learned about the French Impressionists, particularly the artwork of Édouard Manet (1832-1883) and Alfred Sisley (1839-1899). In 1892, while taking painting lessons with Russian naturalist painter Ilya Repin (1844-1930), Jawlensky met realist painter Marianne von Werefkin (1860-1938) who became his mistress and dedicated patron. In 1893 Von Werefkin invited Jawlensky to her father’s estate in Kovno governorate (modern Lithuania) where Jawlensky met Hélène Nesnakomoff (1881-1965), Von Werekin’s personal maid. In time she became Jawlensky’s mistress, mother of his child and, ultimately, in 1922, his wife.

Jawlensky at 23 years old in his military uniform in Russia in 1887.

Marianne von Werefkin.

After seven years studying art in St. Petersburg, Jawlensky’s request to leave the military was granted. He left in early 1896 with a 20-year half pension and the rank of staff captain. That summer Jawlensky traveled through Germany, Holland and Belgium with Marianne von Werefkin and a female friend. Returning to St. Petersburg by way of Paris and London, Jawlensky viewed and admired artwork of J. W. M. Turner (1775-1851) and living artists, James Whistler (1834-1903) and Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898).

In St. Petersburg, Jawlensky entrusted his possessions with family in Russia. With two young painter friends, Igor Grabar (1871-1960) and Dmitrij Kardovskij (1866-1943), he set off to settle in Munich at the end of 1896. Marianne von Werefkin and Hélène Nesnakomoff joined Jawlensky soon after. From his arrival into Munich, Jawlensky lived, with the exception of World War I, in Germany until his death in 1941. In 1897 Jawlensky, Von Werefkin and Hélène Nesnakomoff took an apartment at Giselastrasse 23, a residential street near the Englischen Garten, where they lived until 1914.

Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky in their studio at Gut Blagodat, 1893.

In Munich Jawlensky attended Anton Ažbe’s art school where he met other young German artists, and in 1897, fellow Russian artist, Wassily Kandinsky. Anton Ažbe (1862-1905), a Slovene realist painter, was a master of human anatomy. He enforced figure drawing studies in his classes which Kandinsky loathed but Jawlensky had been studying since 1890. Kandinsky did appreciate Ažbe’s expressed view that an artist should never conform to a theory or set of rules. Ažbe, who died at 43 years old of cancer in 1905, said: “You must know your own anatomy but in front of the easel you must forget it.”4

Anton Ažbe, Self portrait, 1886.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944). Jawlensky met Kandinsky in 1897 in Munich at Anton Ažbe’s art school.

After five months in Munich, Jawlensky traveled to Venice in April 1897. He went with Werefkin, Grabar and Kardovskij, and Anton Ažbe. The next summer, in 1898, Jawlensky returned to Russia with Marianne von Werefkin and Hélène Nesnakomoff to visit family. That autumn the Russian group returned to Munich, where artists continued to draw heads and nudes at Azbé’s school. In 1898 Jawlensky met German Symbolist painter Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) and where, in 1900, Kandinsky matriculated in his art class.5 Jawlensky’s conversation with von Stuck was not on the expression of German character in Symbolist art but the technical issue of working in tempura. In 1898 Jawlensky also received a visit from Russian portraitist Valentin Serov (1865-1911).

Franz von Stuck, Lucifer, 1890, oil on canvas, Bulgaria. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, critics observed that Franz von Stuck (1863–1928) was “one of the most versatile and ingenious of contemporary German artists.” Jawlensky met the renowned Symbolist painter, architect, designer, and co-founder of the Munich Secession in 1898.

Valentin Serov (1865-1911). Self portrait, c. 1888.

In 1899, with Grabar and Kardovskij, Jawlensky executed the ambitious project to open their own painting school in Munich which was short-lived. Kardovskij returned to Russia in 1900 to eventually become a professor at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in 1907. Grabar returned to Russia in 1903 to became director of Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery. Jawlensky, remaining in Munich, was painting still lifes and looking for color harmonies.

Painter Dmitri Nikolayevich Kardovsky, Marianne von Werefkin, Igor Grabar, and Jawlensky in 1900.

Alexei von Jawlensky, Stillleben mit Samowar (Still life with a samovar), 1901.

Jawlensky visited Russia in 1901 with Marianne von Werefkin and Hélène Nesnakomoff. They visited the Ansbaki estate in the Vitebsk governorate (modern Belarus). When Jawlensky fell ill possibly with typhus, he recovered at the Black Sea with Marianne von Werefkin. There he met Kardovskij and his wife, Olga Lyudvigovna Della-Vos-Kardovskaya (1875-1952), a painter who studied at Anton Ažbe’s in Munich in 1898 and 1899.

Olga Lyudvigovna Della-Vos-Kardovskaya, Self portrait, 1917.

The following year, in January 1902, a son, Andreas, was born to Jawlensky and Hélène Nesnakomoff. Jawlensky was continuing to paint still lifes and figural pictures, some of which were influenced by Swedish artist, Anders Zorn (1860-1920). Jawlensky’s pictures featured as models Hélène and her sister, Maria, after she arrived to Munich in November 1902 to aid the new parents. In a visit in 1902, Prussian-born artist Lovis Corinth (1858-1925) advised Jawlensky to send a painting to the Berlin Secession. Jawlensky did so and it was exhibited.

Anders Zorn (1860-1920), Self portrait, 1896.

Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), Self-portrait with Skeleton, 1896, Lenbachaus, Munich. Corinth is a leading figure painter marked by draftsmanship and brushwork. Like Jawlensky, Corinth pursued his artistic training throughout Europe, including in Munich and Paris, and settled permanently in Berlin in 1902. (https://www.kimbellart.org/collection/ap-201701.)

Jawlensky, Hyazinthentöpfe (Haycinth-pots), oil on canvas, 1902. (https://www.artsy.net/artwork/alexej-von-jawlensky-jacinthes

Jawlensky, Stillleben mit orangen (Still Life with Oranges), 1902, oil on canvas.

Jawlensky, Cottage in the Woods, 1903.

Between 1903 and 1907, with Munich as his base, Jawlensky spent much time in France, including in Paris, Brittany and Normandy. In 1903, as Marianne von Werefkin and Georgian artist Alexander Salzmann (1874-1934) traveled in Normandy, Jawlensky was in Paris where he was fascinated with the color and texture of Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890). That same year, in Munich, Jawlensky attended lectures on aesthetics by Theodor Lipps and met the young, eccentric Austrian printmaker Alfred Kubin (1877-1959). Lipps’ theory of aesthetics involved the overlap of psychology and philosophy creating a framework for the concept of Einfühlung (“empathy”) which, defined as “projecting oneself onto the object of perception,” became a key component of Expressionism.5

In 1904, an over-worked Kubin married Hedwig Gründler, an older widow. In early 1906 Jawlensky painted her portrait in his Munich apartment before the Kubins left Munich to live in Austria. In the 23 x 30 inch, oil-on-cardboard portrait, Jawlensky’s colors and modeling of the face showed the influences of French Impressionism and emergent Fauvism.

Jawlensky, writing after his visit to France in 1903. (Dube, p.114).

Jawlensky, Porträt Hedwig Kubin (Portrait of Hedwig Kubin), 1906, oil on cardboard.

Jawlensky stayed in Reichertshausen in the summer of 1904. A woody hamlet 15 miles east of Heidelburg, Jawlensky painted a series of landscapes. In 1905 he followed up with a series of landscapes at Füssen. Jawlensky made friends with Wladimir Bechtejeff (1878-1971), a young Russian painter who relocated to Munich in 1904 in admiration of Jawlensky. Like the older artist, Bechtejeff stayed in Munich until 1914. When Jawlensky visited the 38-year-old German composer Felix vom Rath (1866-1905), son of a wealthy industrialist, Jawlensky saw for the first time at his home a painting by Paul Gauguin (Riders on the Beach of Tahiti, 1902, Essen). At Vom Rath’s home, Jawlensky also met pianist Anna Langenhan-Hirzel (1874-1951).7

Gauguin, Riders on the Beach, 1902, Essen. Jawlensky saw this, his first Gauguin, in a private collection in Germany in 1904.

Jawlensky, Selbstbildnis mit Zylinder (Self-portrait with a top hat), 1904, private collection.

Jawlensky, Hélène im spanischen Kostüm (Hélène in Spanish costume), 1904, Wiesbaden.

Jawlensky, Stilleben mit Weinflasche, 1904.

Jawlensky, Marianne von Werfekin, 1905, Switzerland.

Jawlensky, Portrait de Madame Sid, 1905.

Jawlensky, The Hunchback, 1905.

The middle years of the first decade of the 20th century—1905, 1906 and 1907—were key to Jawlensky’s artistic development. It is likely that Jawlensky traveled to France in 1905. He exhibited six paintings in the Paris Salone d’Automne in 1905, the exhibition which gave birth to the Fauves.

In January 1906 Jawlensky returned to St. Petersburg to exhibit nine paintings. As evidenced in his correspondence, he traveled to France in 1906. He visited Paris and Carantec in Brittany which was a region where Gauguin had worked. That same year Jawlensky exhibited ten paintings at the Paris Salone d’Automne in the newly-formed Russian Pavilion organized by ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929). At the salon, either in 1905 or 1906, Jawlensky met Henri Matisse (1869-1954) whose Fauvist artwork Jawlensky unreservedly admired. During Jawlensky’s visit to France in 1906 he also met Russian painter Elisabeth Ivanowna Epstein (1879-1956) and studied the artwork of Gauguin, Paul Cézanne (who died in October 1906), and Maurice de Vlaminck (1872-1958). Over the next couple of years, Jawlensky wrestled with Cézanne’s influence on his art.8

Jawlensky, writing after his visit to France in 1905 or 1906.

Jawlensky, Stillleben mit Blumen und Früchten, c. 1905.

Jawlensky, Bretonische Bäuerin, 1905.

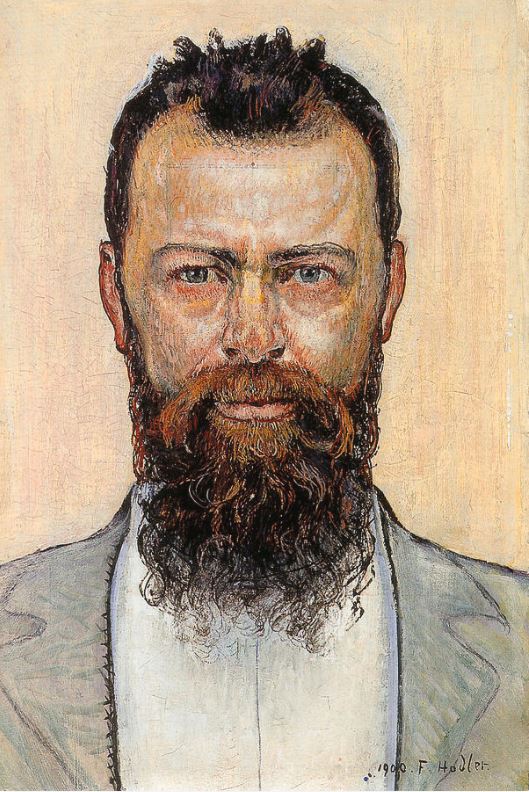

In 1905 and 1906 Jawlensky painted landscapes and character studies, mainly heads. Following the 1906 exhibition in Paris Jawlensky traveled to the Mediterranean resort town of Sausset-les-Pins outside of Marseilles to continue to paint landscapes. Jawlensky returned to Munich by way of Geneva where he visited Swiss Symbolist artist, Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918).

Ferdinand Hodler, Self Portrait, 1900.

Jawlensky, Self portrait, 1905.

Jawlensky spent the fall of 1906, as evidenced in correspondence, in Wasserburg am Inn outside of Munich. He painted landscapes and portraits.

The next year, in 1907, he returned to Wasserburg for a shorter stay with his 5-year-old son, Andreas. In fall 1907 he went to Paris with Hélène Nesnakomoff and Andreas to view the Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d’Automne. He also visited at Matisse’s studio. Near Marseilles to paint landscapes alone afterwards, Jawlensky believed that he achieved his primary goal to use color that was autonomous from the object and based on the artist’s inner feeling. This was a major breakthrough for his painting. Jawlensky’s Mittelmeerkűste (Mediterranean Coast) (below) became the result of these searches and his talisman for landscapes going forward.9

Jawlensky, Mittelmeerkűste (Mediterranean Coast), 1907, oil on hardboard, Munich.

Jawlensky, Wasserburg am Inn, 1907, oil on board.

Jawlensky, Wasserburg am Inn (Melancholy in the Evening), 1907, oil on cardboard.

The landscape Wasserburg am Inn (Melancholy in the Evening) provides insight into Jawlensky’s artistic development at this time. Painted at Wasserburg Am Inn outside Munich in 1907, Jawlensky experimented with applying the techniques of French post-Impressionism, especially Van Gogh, Gauguin and Henri Matisse. The painting and others in this period express Jawlensky’s goal of making unnatural color harmonies and giving visual form to the artist’s inner nature or spirituality. In the manner of Van Gogh, Jawlensky used chisel-like brush strokes and, like Gauguin, thick outlining to achieve a rhythmic, flat, two-dimensional landscape.

Following these travels to Wasserburg am Inn, Paris and Marseilles in 1907, Jawlensky was back in Munich at Christmas and met Dutch Symbolist artist Jan Verkade (1868-1946) in January 1908. Verkade was a Dutch post-Impressionist and Symbolist painter who was a member of the French Nabis under Gauguin in Brittany. Verkade taught Jawlensky and Marianne Weferkin about Gauguin’s ideas on Synthetism. A convert to Catholicism in the mid1890s, Verkade became a Benedictine monk and priest and lived at a monastery in nearby Beuron. In 1907 and 1908 Verkade stayed in Munich and at times painted in Jawlensky’s studio. Jawlensky also learned from Verkade about the writings of French theosophist Edouard Schuré (1841-1929) who influenced the Nabis’ art. In 1908 Jawlensky met Paul Sérusier (1864-1927) who painted The Talisman, an icon to Gauguin’s ideas of Synthetism. 10

Jan Verkade, Self-portrait, 1891.

Paul Sérusier, The Talisman, 1888, Musée D’Orsay.

In Munich in 1908 Jawlensky met other significant figures for his art, including the acquaintance of German painter Karl Caspar (1879-1956) and 22-year-old Alexander Sacharoff (1886-1963). Sacharoff was one of Europe’s most innovative solo dancers. Jawlensky formed a lifelong friendship with Sacharoff and painted his portrait several times between 1909 and 1913. Jawlensky’s 1909 portrait of Sacharoff was painted spontaneously one evening when Sacharoff arrived to Jawlensky’s studio before a performance. In his full theater costume, Jawlensky’s portrait of Sacharoff is notable in that it was one of the first examples of the painter’s motif of wide, piercing eyes.11

Jawlensky, Alexander Sacharoff, 1909.

Jawlensky, Girl with Peonies, 1909. Von der Hevdt Museum.

Vincent Van Gogh, La Maison du père Pilon, 49 × 70 cm, May 1890.

In 1908, with the help of Theo van Gogh’s widow, Jawlensky acquired a Van Gogh painting, La maison du Père Pilon. Jawlensky spent the next three summers—in 1908, 1909 and 1910—in southern Bavaria at Murnau am Staffelsee with Hélène Nesnakomoff, Andreas, Marianne von Werefkin, Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter (1877-1962).

In 1909 Jawlensky met Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), Baltic German painter Ida Kerkovius (1879-1970), and German Expressionist painters Erma Barrera-Bossi (1875-1952) and August Macke (1887-1914). These were all notable figures to the formation of avant-garde expressionism. Jawlensky also met the Ukrainian brothers and avant-garde artists David Burliuk (1882-1967) and Wladimir Burliuk (1886-1917).

Jawlensky’s summer visits to Murnau led to significant development in his painting, This was especially true for his large format portraits. In 1909, his Murnau landscape is a highly stylized reduction of the subject of mountains, trees, and pathway into flat, geometrical forms and harsh, contrasting and unnatural colors influenced by French Cloisonnism and French Cubism. The painting, Murnau landscape, is another example of Gauguin-inspired Synthetism with its high degree of stylization and artificial bright colors. Some of the experimental nature of the painting is indicated by the color samples in the lower righthand corner of the painting.

Jawlensky, Murnauer Landschaft, (Murnau landscape), 1909, oil on cardboard.

It was Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter who discovered Murnau in the spring of 1908 on a bicycle tour. They told Jawlensky about it who visited that summer with Marianne von Werfekin and wrote to Kandinsky to join them. In 1909 Münter and Kandinsky bought a house in Murnau which they called “The Russia House.” The importance of the Bavarian landscape as an inspiration to these artists’ work cannot be underestimated. The Murnau years of 1908 to 1910 was the start and bonding of artists that evolved in 1911 to the formation of The Blue Rider. In 1908 it was Jawlensky’s sharing of his new ideas gained from his visits to France that made him the progressive leader of the group in this period. Accompanied by Marianne von Werfekin, Jawlensky returned to this market town several times where he stayed at Gasthof Griesbräu.12

Jawlensky, Vue de Murnau, c. 1908–1910.

Jawlensky, Skizze aus Murnau (Murnau Sketch), 1908-09, oil on cardboard, Lenbachhaus.

Jawlensky, Weisse Wolke (White Cloud), summer 1909, oil on textured cardboard mounted, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California.

Jawlensky, Kiefer (Pine Tree), summer 1909, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California.

Jawlensky, Sommerabend in Murnau (Summer Evening in Murnau), 1908-09, oil on cardboard, Lenbachhaus.

The painting Summer Evening in Murnau is marked by intense colors, dark contours, simple drawing, and a reduction of form reflecting Jawlensky’s understanding of Gauguin’s “Synthetism.” Sérusier had observed that “art is above all a means of expression.” Within the embryonic Blue Rider group of artists before 1911, Gauguin’s “Synthetism” meshed to Wassily Kandinsky’s idea of “inner necessity.” Intense colors and imaginary reduction of forms that marks German Expressionism had its nascent development in Jawlensky’s paintings at Murnau.13

In March 1909 Jawlensky co-founded Neue Künstlervereinigung München (“New Munich Artists”), an exhibition organization to counteract the inability of official academic art to accommodate avant-garde practice in a new century and counteract the Munich Secession, one of the oldest breakaway modern art groups founded in 1892. Before the first NKVM exhibition in Munich in December 1909, Jawlensky, Kandinsky and other artists resigned from the Munich Secession.14

In 1909 Jawlensky. Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, and art historian Oskar Wittenstein and Heinrich Schnabel elected Kandinsky as NKVM president and Jawlensky as vice-president. German magic realist painter Alexander Kanoldt (1881–1939) was appointed secretary and German painter Adolph Erbslöh (1881–1947) was made chairperson of the association’s exhibition committee. German painter and printmaker Paul Baum (1859-1932) joined as did Russian painter Wladimir Bechtejeff (1878-1971), and German painters Erma Barrera-Bossi (1875-1952) and Carl Hofer (1878-1955). Alexander Sacharoff, Austrian Symbolist printmaker Alfred Kubin, and East European artist Moissey Kogan (1879-1943) soon joined this German avant-garde secession.

The NKVM hosted, in Munich, three annual exhibitions—in 1909, 1910, and 1911. These Munich shows then traveled around Germany. On December 1, 1909 the first New Munich Artists (NKVM) show opened at the Neue Galerie Thannhauser. It included ten painters, one sculptor, one printmaker and other invited artists. Though half of the exhibitors were Russians, these visual artists showed no similarity in style.15 The first show traveled to Brünn, Elberfeld, Barmen, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Wiesbaden, Schwerin, and Frankfurt am Main. It was greeted almost universally with jeers by the public. The critics called it a “carnival hoax” and saw their art as evocative of bad French Impressionism.16

Designed by Kandinsky, the poster advertising for the first exhibition by the Neue Künstlervereinigung München, December 1909. Lenbachhaus, Munich.

The pamphlet for the foundation of the artist association stated, “Our starting point is the idea that the artist not only receives new impressions from the world outside from nature, but that he also gathers experiences in an inner world. And indeed, it seems to us that at the moment more artists are again spiritually united in their search for artistic forms. They are looking for forms that will express the mutual interdependence of all these experiences and which are free from everything irrelevant. The aim is that only those elements which are actually necessary should be expressed with emphasis. In other words, they are striving for an artistic synthesis This seems to us a solution that is once again uniting in spirit an increasing number of artists.”17

Jawlensky, Schwebende Wolke (Floating Cloud), 1909-10, oil on cardboard, 32.9 x 40.8 cm, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California.

In 1909 and 1910, working in Murnau am Staffelsee, Alexei Jawlensky took outings into the foothills of the Bavarian Alps to paint. It was a manageable walk for the 45-year-old artist into surrounding mountains and woods. Floating Cloud is one painting that is part of a group of artworks from this period that evokes mountains, clouds and trees. The painting is undated so there is no irrefutable proof it was painted in 1910 — Jawlensky’s final summer stay in Murnau — but its varied and discordant colors and tendency to synthetic composition points to having been created in 1910 or summer 1909.

Its foreground green, dark trees, pink clouds, and orange sky are formal elements found in landscapes from the period. The painting had been later discarded by the artist though under exactly what circumstances is unclear. When World War I began in August 1914, Russian-émigré Jawlensky had to leave works behind in Munich to be retrieved in 1921 and 1922. Floating Cloud was brought to the United States in 1924 by its owner, Galka Scheyer (1889-1945). Jawlensky began his series of monumental heads by 1910 that defined his artwork in the years ahead.

In Floating Cloud, shapes are precisely delineated; the chain of the pine trees’ triangular forms are echoed in the repetition of the mountain chain’s pointed shapes in the background. The clearly defined planes of foreground, middle distance, and background are parallel to the picture plane but compressed into a narrowed, stage-like area. Jawlensky also began many figural drawings of the female nude in 1910 though he did not use them for paintings much. Its formal properties as well as subject is similar to paintings of Henri Matisse in this time period.18

Jawlensky, Sitzender Weiblicher Akt (Seated female nude), c. 1910 oil on cardboard.

Jawlensky, Girl with the Green Face, 1910, oil on hardboard, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Meanwhile Kandinsky’s Blue Mountain in 1908-1909 continued to demonstrate his direction towards abstraction. In the picture, a blue mountain has a yellow and a red tree on each side of it. A procession of human figures and horses crosses in the foreground. Their faces, clothing, and saddles are composed of bold colors, with little linear detail. The flat, contoured colored shapes indicate French Fauvist influences.

Kandinsky, Der Blaue Berg (Blue Mountain), 1908-1909, Guggenheim, New York.

Kandinsky, 1908, oil on card, Murnau, Landschaft mit Turm (Murnau Landscape with Tower Centre), Pompidou, Paris.

Floating Cloud was exhibited by Jawlensky, along with ten other of his paintings, in the important second exhibition of the New Artists’ Association which opened in September 1910 at the Neue Galerie Thannhauser. In that second show, Jawlensky also exhibited Child with Doll (Kind mit Puppe). In that painting, the sitter was a local school girl in Murnau. In 1912 Jawlensky returned to the subject of a girl with doll and gave one such picture to Franz Marc.19

Jawlensky, Kind mit Puppe (Child with Doll), c. 1910, oil on paper mounted on cardboard, Norton Simon.

Heinrich Thannhauser (1859-1934) opened his gallery in Munich in 1904. In 1908 it hosted an important exhibition of over ninety works by Vincent van Gogh. The Neue Galerie Thannhauser became the leading proponent of international modern art in Germany in the 1910’s exhibiting French Impressionist and post-Impressionist art as well as German and other international modern artists. Designed by Paul Wenz in the glass-domed Arcopalais developed by Georg Meister and Oswald Bieber at Theatinerstraße 7 in the heart of Munich’s shopping district, several rooms of the Neue Galerie Thannhauser were set up as fashionable domestic environments. With Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc in December 1911, Thannhauser organized the first exhibition of Der Blaue Reiter.

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of the Art Dealer Heinrich Thannhauser, 1918, Kimbell.

The second NKVM exhibition is important in that it was the world’s first modern art exhibition that assembled an estimable scope of international artists represented by Germans, French, Russians, and others.

The second exhibition expanded to include French Cubists, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, Postimpressionists, and Fauvists, such as Henri Le Fauconnier, Andre Dérain, Maurice Vlaminck, and Kees van Dongen.20 The historic showing at the Neue Galerie Thannhauser afterwards traveled to Karlsruhe, Mannheim, Hagen, Paul Cassirer Berlin, Leipzig, Galerie Arnold Dresden, Munich Weimar, and the Neue Secession Berlin. The exhibition was the precursor of future great international shows such as the Cologne Sonderbund in 1912 and New York Armory Show in 1913. The Armory Show, in which Neue Galerie Thannhauser participated, introduced European Modernism to the United States.

The Munich gallery occupied over 2,600 square feet of the glass-domed Arcopalais and was divided between two floors. Nine exhibition rooms were on the ground floor with a skylit gallery on the floor above. Similar to the first NKVM exhibition, the Munich public derided the offerings of the second. The German press called for its closure as the artists were “anarchists.” A small group of sympathizers gathered to support the avant-garde exhibitions including other modern artists and some German curators, one of whom was afterwards dismissed from his official curatorial posts because he espoused contemporary nonacademic views.21

Picasso, Head of a Woman, spring 1909, gouache, watercolor, and black and ochre chalks, manipulated with stump and wet brush, on cream laid paper. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Gabriele Münter, Landschaft mit weisser mauer (Landscape with a White Wall), 1910, oil on hardboard, Hagen.

The second exhibition catalog had five articles and was illustrated by Picasso’s Head of a Woman. In addition to Jawlensky’s 11 art works, Gabriele Münter exhibited 7 art works, including Landscape with White Wall from 1910. Kandinsky had carefully defined his different categories for a painting—an impression; an improvisation; and a composition.22 Kandinsky exhibited examples of all three at the second NKVM show in September 1910, including Composition no.2 of early 1910 and Improvisation no.12-The Rider painted in summer 1910.

Kandinsky, Improvisation no. 12 The Rider, summer of 1910.

Karl Ernst Osthaus (1874–1921), an important German patron of European avant-garde art, founded the Folkwang Museum at Hagen, Germany, in 1902. Following the second New Artists’ Association exhibition, Osthaus organized an even larger exhibition of Expressionist painting with works by Jawlensky and Kandinsky.

Ida Gerhadi, Portrait of Karl Ernst Osthaus, 1903.

By 1910, with 20 years of art practice, Jawlensky had built up and continued to expand his circle of collectors. His friendship with Cuno Amiet (1868-1961), a pioneer of modern art in Switzerland, likely started in 1909. In Still Life with Vase in 1909 Jawlensky painted in simplified forms, vivid colors, and decorative lines, following the example of Henri Matisse.23 From 1906 to 1911, Jawlensky’s still lifes were influenced by Matisse who Jawlensky met in Paris. In 1909 and 1910 Jawlensky painted still lifes that are among his finest works. Starting in 1911, Jawlensky focused increasingly on the human face. Regarding his still lifes, Jawlensky observed that he was not searching for a material object, but by way of form and color, “want[ing] to express an inner vibration.”24

Jawlensky, Stilleben mit Vase und Krug (Still Life with Vase and Jug), 1909, oil on Hardboard, Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

Jawlensky, Stilleben mit Früchten, (Still Life with Fruit), c. 1910, oil on cardboard.

In late 1909 and into early 1910 Marianne von Werefkin visited family in Lithuania. Since the early 1890’s, Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin were a pioneering artist couple of the avant-garde. With the founding of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München in 1909, from which The Blue Rider emerged in 1911, individually and as a couple they advanced modernism as a conceptual and creative force making a significant contribution to early 20th century modern art. Each had found the other’s soulmate in which their interpersonal relationship was intense and complex. Lily Klee (1876-1946), wife of painter Paul Klee, wrote in her memoirs that Jawlensky and von Werfekin were “no marriage” but rather “an erotically platonic friendship love.” Though their domestic partnership ended, they remained loyal partners and art colleagues. A wealthy, Russian aristocrat, Von Werfekin was, as a painter and knowledgeable supporter of their theories and ideas, an influential force in the NVKM and Blaue Reiter that benefitted these progressive artists’ work.25

Marianne von Werefkin, Selbstbildnis I (Self portrait I), , c. 1910, tempera on paper on hardboard, Städtische Galerie am Lenbachhaus Munich.

In 1910, Jawlensky met German painter and printmaker Franz Marc (1880-1916) and, in 1911, after seeing the second exhibition of the Neue Künstlervereinigung, Marc joined NKVM. Pierre Girieud and Henri Le Fauconnier also joined. That same year Kandinsky, Marc, and others in the NKVM resigned and founded Der Blaue Reiter.

The approach of Le Fauconnier’s painting influenced by Gauguin and Emile Bernard greatly influenced Jawlensky’s work in this period. Kandinsky’s mediation led to Jawlensky exhibiting 6 paintings in Vladimir Izdebsky’s salon in Odessa and Kiev from December 1909 to February 1910 and again in Odessa at the same venue in December 1910. Jawlensky also exhibited at the Sonderbund Westdeutscher Künstler in Düsseldorf. In 1911 Jawlensky visited Franz Marc in Sindelsdorf, south of Munich and spent that summer with his family and Marianne von Werefkin in far northern Germany. At Prerow on the Baltic Sea he painted landscapes and large figural works in bright strong colors. The artist considered his time at Prerow as “a turning point in my art.”

Jawlensky, Blonde, c. 1911, oil on carboard. The time Jawlensky spent in the summer of 1911 on the Baltic coast was a turning point in his art.

Jawlensky, Blühendes Mädchen (Blossoming Girl), c.1911. Norton Simon. The precise date and the sitter are unknown, and the work was titled much later and not by Jawlensky.

Jawlensky, Turandot I, 1912, Privatsammlung.

In Fall 1911 Jawlensky traveled to Paris with von Werefkin where he saw Matisse, visited with Pierre Paul Girieud (1875-1940) and met Kees van Dongen (1877-1968). Later that year Girieud stayed with Jawlensky in Munich where Heinrich Campendonk (1889-1957) visited him in the studio in November. In December 1911 Kandinsky, Marc, Münter, Kubin and Macke resigned from the Neue Künstlervereinigung and Kandinsky and Marc founded Der Blaue Reiter.

The fault line between NKVM and The Blue Rider was over the degree of artistic importance of representation (Kanoldt and Erbslöh) versus nonrepresentation (Kandinsky, Marc, Kubin, Münter) in avant-garde German expressionism. The resignations came after Kandinsky and Marc had forcefully advocated for a jury show and, then, having overcome some other members’ intractable resistance, one of Kandinsky’s large format pictures was rejected by the jury for the 1911 NKVM show.26

Adolf Erbslöh, Mädchen mit rotem Rock (Girl with Red skirt), 1910, Von der Heydt Museum.

Alexander Kanoldt, Nikolaiplatz, 1910-13.

Jawlensky, Yellow Houses, 1909.

Kandinsky in 1910 produced the first painting, a watercolor, that was completely nonrepresentational—Untitled in the collection of the Pompidou in Paris. In late 1911 Kandinsky, seeing his painting as a triumph of art over the external object, published his art theories in a major treatise entitled Über das Geistige in der Kunst (“On the Spiritual in Art”). Kandinsky, who was informed on European modern art currents, synthesized and personalized ideas that were broadly available at the turn of the 20th century—one, that there is an order of pre-eminent human experiences; second, that all artworks possess spiritual or expressive qualities to be researched, expanded to the sensory faculties and refined to and superseded by physical and psychological effects; and, third, that the essential nature of art makes it autonomous of naturalistic external appearances.

Modern, specifically abstract, art, through the artist’s practice of relaying his emotive and spiritual qualities can, within the broad engagement of culture as well as art that possesses an autonomous spiritual-expressionist nature, can become a barometer for social progress and gauge the spirit of the age.

Since art is the embodiment of spirit or expression, Kandinsky postulated no specific formal or stylistic language—form is meaningless apart from the expression, the making visible, of the artist’s inner reality. This is true for the “great” avenues of realism or abstraction. The immediate use of Cubist and Futurist forms dematerialized further into a spiritual significance of colors and nonrepresentational forms in Abstract Expressionism.27

The third and final NKVM show was held in December 1911 at Neue Galerie Thannhauser. It featured 58 paintings and 8 illustrations by eight of the original and early member artists, namely, Jawlensky, Adolf Erbslöh, Alexander Kanoldt, Erma Barrera-Bossi, Wladimir von Bechtejeff, Moissey Kogan, Pierre Girieud and Marianne von Werefkin. It was hardly mentioned in the German press.

The show closed on January 12, 1912 and likely did not travel though scheduled to do so. In the same month of December 1911 and in the same gallery Der Blaue Reiter hosted its first exhibition. Though Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin sympathized with Kandinsky and der Blaue Reiter, they did not follow into the group until 1912.

Neither did Jawlensky follow Kandinsky into nonrepresentational abstract art. He continued with representational motifs. Jawlensky was more concerned with synthesis—a term and practice with a broad, diverse, and even contradictory definition. For Jawlensky, synthesis occurred between impressions of the outer world and experiences of the artist’s inner world. In terms of his art, it involved the “outer” object and “inner” expressive, unnatural colors. It involved the “outer” pictorial composition and “inner” colors and forms, with these categorical elements being fluid in terms of their opposition.

Kandinsky, Untitled, 1910, watercolor, Indian Ink and pencil on paper. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Reputedly the first nonrepresentational (abstract) painting.

Franz Marc, Pferd in Landschaft (Horse in a Landscape), 1910, oil on canvas, Folkwang Museum, Essen.

Jawlensky, Hügel (Hills), 1912, oil on hardboard, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund.

Jawlensky, Landschaft mit gelbem Schornstein (Blue mountains landscape with yellow chimney), 1912, Museum Wiesbaden.

Jawlensky, Jünglingskopf (Head of a Young Man, called Hercules), 1912, oil on hardboard, Dortmund.

Kandinsky, Der Blaue Rider (The Blue Rider), 1903, private collection.

NOTES

1. German Unification – Confronting Identities in German Art: Myth, Reactions, Reflections, Smart Museum, Chicago, 2002, pamphlet.

2. World War I casualties- http://www.centre-robert-schuman.org/userfiles/files/REPERES%20%E2%80%93%20module%201-1-1%20-%20explanatory%20notes%20%E2%80%93%20World%20War%20I%20casualties%20%E2%80%93%20EN.pdf

3. Idea of German art–https://www.britannica.com/place/Torzhok

4. Ažbe Quote- Boehmer, Konrad, Schonberg and Kandinsky: An Historic Encounter (Contemporary Music Studies), Routledge, 1998, p. 209.

5. matriculated at von Stuck’s- Watson, Peter, The German Genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century, HarperCollins, 2010, p. 515.

6. Trip to Paris and Brittany– Clemens Weiler, Jawlensky: Heads, Faces, Meditations, Pall Mall Press, 1971.; Theodor Lipps– Encyclopedia Britannica.

7. Hedwig Kubin—Hoberg, Annegret, The Blue Rider in the Lenbachhaus, Munich, Prestel, Munich, 1989. Wladimir Bechtejeff —https://www.kreisbote.de/lokales/garmisch-partenkirchen/schlossmuseum-murnau-zeigt-bilder-wladimir-bechtejeff-9688996.html

8. Paris Salone d’Automne and Matisse- Donald Gordon, Modern Art Exhibitions 1900-1916, Munich, 1974.

9. On Mediterranean Coast painting- Elger, Dietmar, Expressionism: A Revolution in German Art, Taschen, Cologne, Germany, 1998, p.166.

10. Melancholy in the evening –https://mfastpete.org/obj/wasserburg-on-the-inn-melancholy-in-the-evening/; Verkade- http://www.peterbrooke.org/art-and-religion/denis/intro/beuron.html

11. Sacharoff portrait—Hoberg, Blue Rider in Lenbachhaus.

12. Murnau art colony—Watson, German Genius, pp. 516-518; progressive artist- Hoberg, Blue Rider in Lenbachhaus; Barnett, Vivian Endicott, The Blue Four Collection at the Norton Simon Museum, 2002, p. 84.

13. Hoberg, Blue Rider in Lenbachhaus.

14. Selz, Peter, German Expressionist Painting, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1974. p.185.

15. ibid., p 186 and 191.

16. First NKVM exhibition travel cities– Hoberg, not paginated; carnival hoax—Selz, German Expressionist Painting, p. 191.

17. Elgar, Expressionism, p. 168; Selz, German Expressionist Painting, p 191; Watson, German Genius, p. 516.

18. Selz, p. 195; Barnett, p. 86.

19. Barnett, p. 90.

20. Hoberg (not paginated); Selz, p.193.

21. Selz, p. 196.

22. “An impression is a direct impression of nature, expressed in purely pictorial form. An improvisation is a largely unconscious, spontaneous expression of inner character, non-material nature. A composition is an expression of a slowly formed inner feeling, tested and worked over repeatedly and almost pedantically. Reason, conscious, purpose, play an overwhelming part. But of calculation nothing appears: only feeling…” Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, quoted in Selz, p.196.

23. Elgar, Expressionism, p. 169.

24. Hoberg, not paginated.

25. Elgar, Expressionism, p.177.

26. Selz, p. 197.

27. Harrison, Charles & Paul Wood, Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford U.K. and Cambridge, MA, 2000, p 86); Chipp, Herschel B., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1971, pp. 126-127; Kern, Stephen, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1983, p. 203).

Bibliography

Barnett, Vivian Endicott, The Blue Four Collection at the Norton Simon Museum, 2002.

Boyle, Nicholas, German Literature: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford New York, 2008.

Chipp, Herschel B., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1971.

Dube, Wolf-Dieter, Expressionism, Oxford University Press, New York and Toronto, 1972.

Elger, Dietmar, Expressionism: A Revolution in German Art, Taschen, Cologne, Germany, 1998.

Harrison, Charles & Paul Wood, Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford U.K. and Cambridge, MA, 2000.

Hoberg, Annegret, The Blue Rider in the Lenbachhaus, Munich, Prestel, Munich, 1989.

Kern, Stephen, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1983.

Koldehoff, Stefan and Chris Stolwijk, editors, The Thannhauser Gallery: Marketing Van Gogh, Mercatorfonds, Brussels, 2018.

Selz, Peter, German Expressionist Painting, University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1974.

Taylor, A.J.P., Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman, Vintage Books, New York, 1967 (originally 1955).

Watson, Peter, The German Genius : Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century, HarperCollins, 2010.