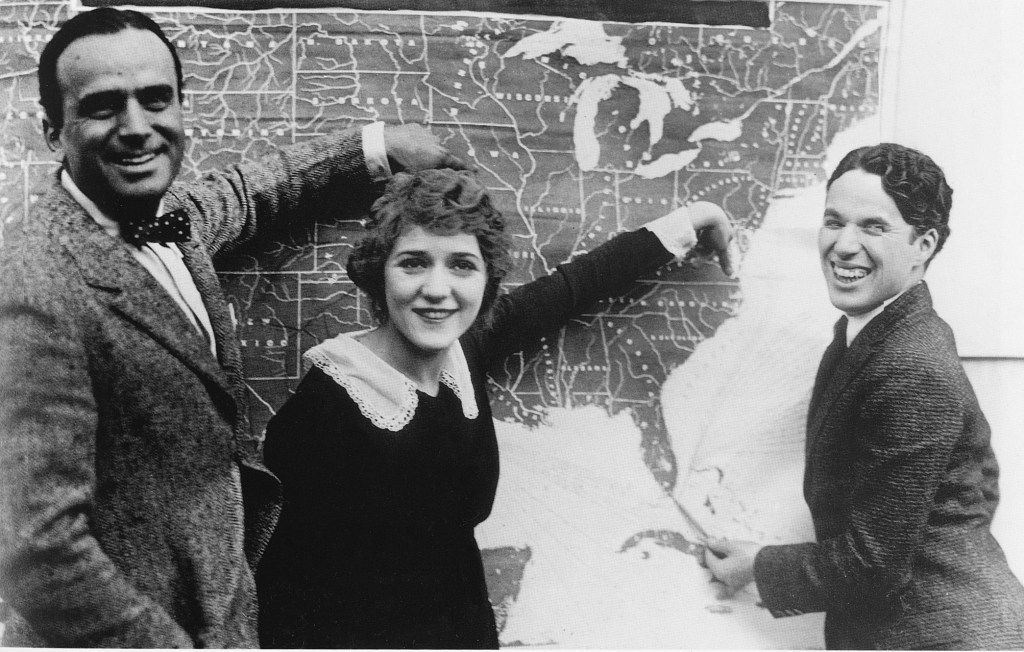

FEATURE image: United Artists founders in 1919, (Left to right) Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939), Mary Pickford (1892-1979). Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) and D.W. Griffith (1875-1948).

By John P. Walsh

It is debated whose brainchild the United Artists Corporation (UA), founded in 1919, ultimately was. Was it Mary Pickford’s and Douglas Fairbanks’ theatrical lawyer and a later UA executive who advised them to found an artist-controlled movie company or UA’s first president, a former U.S Treasury Department official, who suggested Douglas Fairbanks start a distribution company for his films or was it a publicity man for one of the majors who suggested to UA’s first general manager to create a movie studio run by artists for artists – or, finally, was it, as Charlie Chaplin claimed, by way of his elder half-brother Sydney who had hired a pretty girl to spy on another studio’s imminent potential merger and whose culled information led directly to founding their own?1 Whatever or whoever was the conduit or original source, in 1919, four of Hollywood’s legendary film artists — actors Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939), Fairbanks’ future wife, Mary Pickford (1892-1979), Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977), and “the Father of Film Technique” director D.W. Griffith (1887-1948)- formed United Artists, one of Hollywood’s name-brand film studios.

Distinct from other movie studios, UA was especially founded by artists for artists. From His Majesty, The American in 1919 starring Douglas Fairbanks that premiered in New York City at the newly-built Capitol through to The Underdoggs scheduled for 2024, a comedy starring Snoop Dog – and many hundreds of major motion pictures in between – United Artists’ impact on the entertainment industry and culture has been highly significant in that its range of film product envisioned and presaged the artist/ producer-driven film industry that is normal today. Yet United Artists was also more as it allowed independents to make their films free of heavy-handed interference from the higher ups which was often the case at the majors. Such freedom in the marketplace could be risky and United Artists’ survival through the decades is nothing other than extraordinary.

The following artist corporate manifesto was released to the press on February 5, 1919. Over 100 years later it remains prescient for many reasons including a warning about the use of technology in filmmaking (“machine-made entertainment”) and freedom of choice for the consumer in terms of viewership (“not force[ing] upon him program films he does not desire”) – A new combination of motion picture stars and producers was formed yesterday, and we, the undersigned, in furtherance of the artistic welfare of the moving picture industry, believing we can better serve the great and growing industry of picture productions, have decided to unite our work into one association, and at the finish of existing contracts, which are now rapidly drawing to a close, to release our combined productions through our own organization. This new organization, to embrace the very best actors and producers in the motion picture business, is headed by the following well-known stars: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith productions, all of whom have proved their ability to make productions of value both artistically and financially. We believe this is necessary to protect the exhibitor and the industry itself, thus enabling the exhibitor to book only pictures that he wishes to play and not force upon him (when he is booking films to please his audience) other program films which he does not desire, believing that as servants of the people we can thus serve the people. We also think that this step is positively and absolutely necessary to protect the great motion picture public fromthreatening combinations and trusts that would force upon them mediocreproductions and machine-made entertainment.2

In a short 30 years, by the early 1950’s, with the demise of the studio system and the rise of broadcast television, UA would bring this visionary independent investor and producer driven film product to the world as the business template for how all films in and outside of Hollywood would be made. In 1919, United Artists was originally conceived as a prestige studio that distributed some of the industry’s best larger budget pictures. By the 1940’s it had evolved to add less expensive film products that met audience demands and kept the studio’s distribution networks humming. As capital and power tends towards concentration in a capitalist economy, the notion for a nimble, relatively low overhead movie-making patron facilitating production planning and distribution of films by independent producers proved a vital idea whose relevancy renewed itself through the years.3

In contrast to the major studios, such as MGM, Paramount, Fox, RKO, and Warner Bros., which had production, distribution and exhibition arms, United Artists focused solely on distribution. Unlike the majors, United Artists had no star stable, no studio facilities to speak of, no directors, no technicians, no chain of theaters, no house style, but, functioned as a distribution outlet for independently-made productions. In that way, UA was responsible for all phases of an independent production company’s film releases. This included the layers of market testing desired, the planning (including some financing) and booking of production releases, sundry marketing, and settlement matters following release. Distribution duties ranged from pre-production to marketing assistance as well as a bird’s-eye evaluation during production. Post-production distribution of motion pictures to the country 23,000 theatres in the 1930’s was an umbrella term for what was really a chain of complex business actions starting at the beginning of a film project to its being shown flickering on a local screen.

In the beginning: the 1920’s.

Throughout the silent era’s heyday and ultimate demise—the 1920’s—UA was clearly distributing films of its four founders which was a large reason for the company’s genesis. This soon included bankable silent film stars, such as Gloria Swanson (1889-1983). Lillian Gish (1893-1993), Buster Keaton (1895-1966) and Norma Talmadge (1894-1957). UA had no shortage of money-making hits in the roaring ‘20’s. There were melodramas such as Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) to his Way Down East (1921) and comedies starring Mary Pickford, including Pollyanna (1920) and Little Annie Rooney (1925). Douglas Fairbanks starred in UA crowd-pleasers in roles that in the 1930’s sound era was played by Errol Flynn, such as The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1923) and The Thief of Bagdad (1924).

Gloria Swanson, born in Chicago, was, at 26 years old, considered the most bankable silent film star of the time. In a successful career in film since 1918, she signed with United Artists in 1925 with UA chairman of the board Joseph Schenck who was brought in the year before. It was a six-picture distribution deal, and her production company was advanced financial loans through United Artists’ own Art Cinema Corporation subsidiary. Swanson also agreed to invest in UA by buying $100,000 of preferred stock. These financial terms proved difficult for Swanson to repay later and required the services of financier Joseph P. Kennedy (1888-1969) who reconfigured her business portfolio to meet her obligations and produced one of her films.4 Meanwhile, her UA debut, The Love of Sunya, basically broke even. Swanson made two other UA films that were critical and financial successes –Sadie Thompson in 1927 with director Raoul Walsh (1887-1980) and The Trespasser, one of Swanson’s few sound films. The latter was directed by Edmund Goulding (1891-1959) and produced by Kennedy in 1929. For both of these films, Gloria Swanson received Academy Award nominations for Best Actress.

As its founders first looked to protect their public image and screen product, United Artists opened its doors to an array of outside suppliers expanding their business operations. In 1929 UA produced 18 pictures – a company record – and, in the next few years, was expanding to distribute films of Samuel Goldwyn, Howard Hughes, Joseph Schenck, Walt Disney, Alexander Korda, David O. Selznick, and Walter Wanger, among others. With the onset of talkies in 1927 and the Great Depression in 1929 the new pressures on the movie studios were enormous. While having built their reputation on silent film stars and watching their film output dwindle 25% in the early 1930’s, UA benefited from the management of Joseph Schenck (1876-1961) who facilitated the release of several popular money-making features by Samuel Goldwyn (Palmy Days), Howard Hughes (The Front Page – nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture), Charlie Chaplin (City Lights) and Alexander Korda (The Private Life of Henry VIII).5

In 1926, Joseph Schenck in a visionary move, set up the United Artists Theatre Circuit which selectively acquired certain first-run theatres in major markets to show their pictures. This also had the effect of the majors working more accomodatingly with an astute competitor and showed UA pictures in their venues. Yet, since United Artists, as part of its nimble, skeletal organization, did not have a portfolio of theatres like MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., Fox, and RKO – collectively, these majors owned about 15% of the country’s total number – meant that when times were bad, such as in the Great Depression, UA was not impacted as negatively by the sudden decline in movie attendance or dipping real estate values. Moreover, UA’s low operating overhead included a smaller staff that resulted in less lay-offs in hard times. Under Joseph Schenck, UA started in the 1930’s to invest money in future productions with profit-sharing in addition to simply loaning money to producers to be paid back with interest in post-production (Gloria Swanson’s deal). After Joseph Schenck partnered with Darryl F. Zanuck (1902-1979), formerly of Warner Bros., to form Twentieth Century Pictures in 1933, they produced most of UA’s films in 1933 and 1934. When Schenck left United Artists in 1935 after being rejected for partnership6 he merged with Fox Films to form Twentieth Century-Fox and became its chairman. The situation placed United Artists in a difficult position of having to replace their leading producer. The leadership issue was, arguably, not be addressed by UA until Krim and Benjamin in the 1950’s. After-Schenck’s departure, notable filmmakers slowly fled UA, though this was also the natural condition of the movie business, especially among the independent-minded, to find greener pastures. Disney exited in 1936 and Goldwyn in 1940, both moving to RKO, and William Wanger moved in 1941 to Universal Pictures. Not until in the post-war period did Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin look to recruit vibrant new leadership for UA following the demise of the studio system in the late 1940’s and the rise of television at the same time – and would swiftly result in their own departures from the company.

Meantime, in 1935 David O. Selznick (1902-1965) joined UA and released his pictures – in 1936, Little Lord Fauntleroy and The Garden of Allah; in 1937, A Star is Born, The Prisoner of Zenda, and Nothing Sacred; in 1938, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Young at Heart; and, in 1939, Made For Each Other and Intermezzo, starring Ingrid Bergman who Selznick introduced to American film audiences. These films were jewels for UA and made a fortune for the studio. Selznick International Pictures’ Gone With The Wind should have been released through UA but part of the condition of MGM lending Clark Gable to the project was that the film would be distributed by Gable’s home movie studio. In the 1940’s Selznick released Rebecca (1940), Since You Went Away (1944), I’ll Be Seeing You (1945) and Spellbound (1945) through UA.

Other notable films from the 1930s released by UA included Walter Wanger’s Trade Winds (1938), John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), and Samuel Goldwyn’s Wuthering Heights (1939). Before Goldwyn’s departure in 1940 under circumstances not unlike Joseph Schneck in 1935 – a star producer wanting to buy in or buy out UA- he left to form his own movie enterprise after 50 critically acclaimed and money-making films in 14 years for United Artists.

The War Years.

Seeking diversion, news information, and community camaraderie, America continued to go to the movies in record numbers before and during World War II (1939-1945). In 1938 there were 80 million tickets sold every week.7 The U.S. population in 1940 was about 130 million people and in pre-Pearl Harbor 1941 about 55 million of them (about 40% ) attended the movies each week. 8 In three years, by 1944, weekly attendance numbers nearly doubled to 100 million people – or about 75% of the U.S. population.9 By comparison, starting in the early 1970’s and through to today, the trend is very different. About 10% of the population may attend the movies each week at movie theatres. The early 1940’s was booming times for the movie industry whose contemporaneous films often extolled democracy’s virtues as well as a sentimental Homefront along with providing the outright escapist fare such as Westerns, comedies and musicals. Despite this prosperity UA’s film product was mostly undistinguished in this period and their income fell slightly from the end of the pre-war period.10 After the war, movie attendance levels dropped as people returned to start families, and go back to school and work. In response, the movie industry released less product – and the decline spiraled so that by the end of the decade of the 1940’s UA was in debt and ripe for a takeover.

Notably, at the end of the decade, beyond film noir with, as Michael F. Keaney points out, “its thematic criminal content” and “Emphasis on obsession, desperation, alienation, and paranoia” that is noted for its “dark visual style,“11 United Artists’ releases contributed to the new willingness after the war and ushering in of the Atomic Age to present serious social issues in films such as Home of The Brave (1949) exploring issues of race bigotry. Produced by Stanley Kramer, directed by Mark Robson, and written by Carl Foreman Kramer and others would continue to explore these social issues in the future.

The Post War Era: 1950’s to 1970’s. Krim and Benjamin.

In 1951, Arthur B. Krim (1910-1994) and Robert Benjamin (1909-1979), lawyers and producers, were given leadership at UA and, based on their immediate success, soon acquired the movie studio. The duo unabashedly practiced the capital-producer-driven model for making movies which has since defined the film industry business model. United Artists’ visionary low overhead approach from its inception proved prescient for film production outside the once all-encompassing major studio system. Continuance of a skeletal staff which caused independent producers, notably Samuel Goldwyn, to flee from its sometime sloppy operations and no studio space – such could be leased from Pickford and Chaplin – became the de facto method to critical and box office success. 12 When Krim and Benjamin took over United Artists, stockholders gave them three years to make a profit. They did it in six months.13 United Artists devised a strategy based on financing and distribution of independent production that quickly and sustainably transformed the company into an industry leader. The revamped 1950’s United Artists worked with producer Sam Spiegel (1901-1985) and director John Huston (1906-1987) to have two upfront hits – The African Queen in 1951 and Moulin Rouge in 1952. This was followed up by High Noon in 1952 which was nominated for 7 Academy Awards and won four. United Artists was soon working closely with Stanley Kramer, Otto Preminger, Hecht-Hill-Lancaster Productions (actor Burt Lancaster’s production company) and other free-agent actors and others wanting to produce and direct. UA’s innovative and successful business model made the movie studio run by artists for artists the envy of the film industry so that, by the 1960’s, the majors were imitating them.

“The African Queen (1951)” by Wasfi Akab is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Surviving Founders Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin Sell.

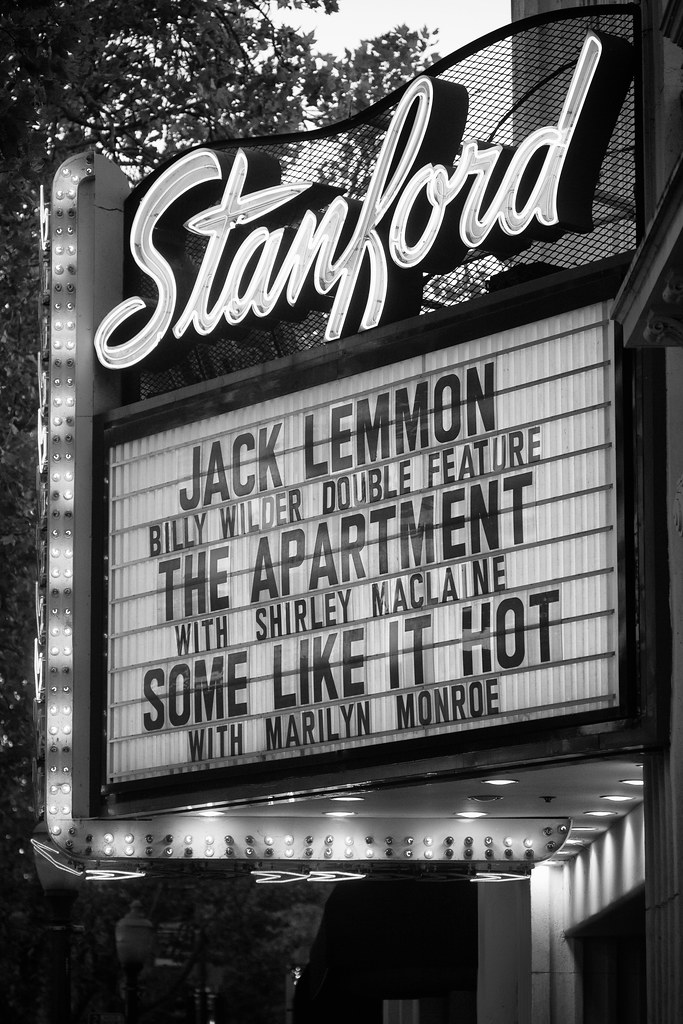

By 1956 both Chaplin and Pickford had divested their shares to Krim and Benjamin who came from Eagle-Lion Films. United Artists then made a motion picture, Marty in 1955, that won four Oscars, including Best Picture. In 1957, a social drama, 12 Angry Men, was Oscar-nominated multiple times. There was also The Bachelor Party, an Oscar-nominated follow-up to Marty, in 1957 and Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones in 1958. UA also released some of the era’s great comedies, including Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot in 1959 and The Apartment in 1960 which won the Best Picture Oscar. In the 1960’s Wilder did some of his best work with United Artists including, all of them box office hits, One, Two, Three in 1961, Irma La Douce in 1963, Kiss Me, Stupid in 1964 and The Fortune Cookie in 1966.

“Some Like it Hot” by Thomas Hawk is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

In 1957 Krim and Benjamin did something the founding owners didn’t do and if they had the studio’s history, likely starting in the mid-1930’s, would be very different: they took UA public. Before the 1950’s was finished, United Artists was the envy of the Hollywood motion picture industry, very profitably producing films, television shows, and records.14 Arthur Krim and Robert Banjamin remained with UA until 1978 when, with others, they created Orion Pictures. From 1978 to 1992, Krim attempted to mirror UA’s success with a company that, since 1997, is a subsidiary of MGM.

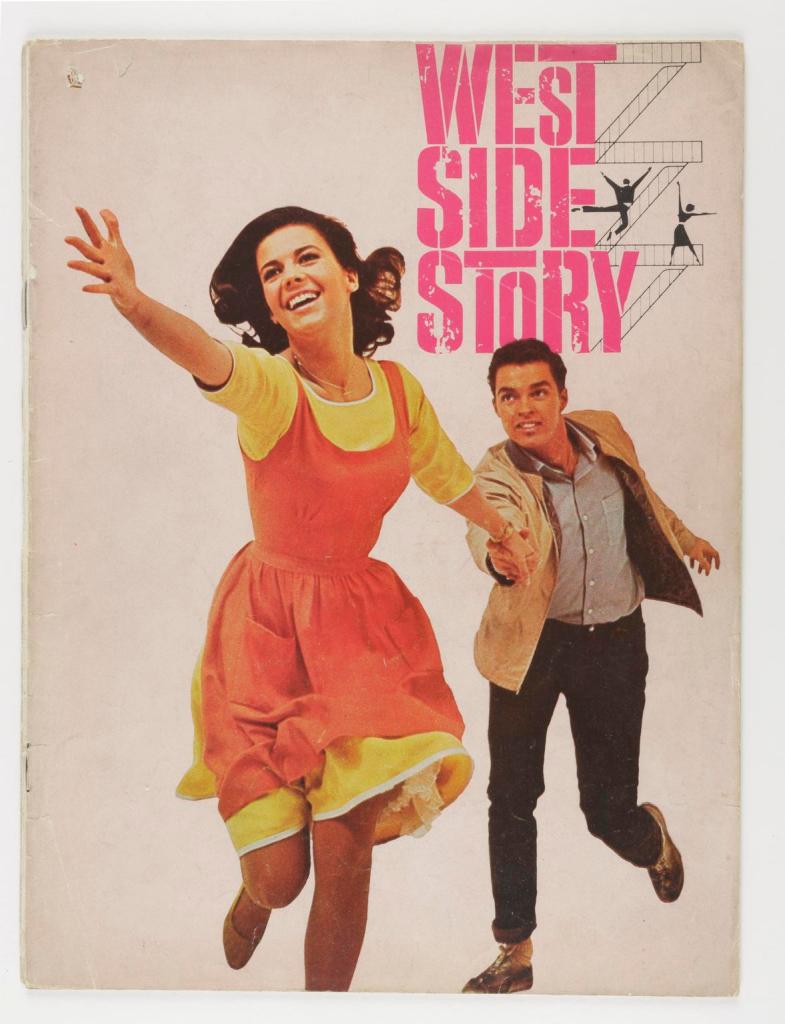

In 1961, United Artists released West Side Story which won a record 10 Academy Awards including Best Picture. Producer-Director Stanley Kramer with whom United Artists first started working in 1958, released Judgement At Nuremburg in 1961 and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World which, in its homage to slapstick, featured a Who’s Who ensemble cast of stage and screen comedians and became a box office smash.

It was also in 1963 that United Artists backed the first film in the James Bond 007 franchise – Dr. No. Starting in 1964, they also backed The Pink Panther films directed by Blake Edwards and Bud Yorkin. Starting in 1964, Clint Eastwood was well on his way to becoming a star by way of his UA-backed spaghetti westerns. These and other films looked to satisfy the younger movie-going demographic that increasingly desired depictions of sex and violence at the cinema.

In 1964 and 1965 United Artists got on board to introduce the Beatles to U.S. film audiences with A Hard Day’s Night and Help. Both films were phenomenal money makers. In 1965 UA had the means to finance, at $20 million, the most expensive film ever made up to that time: George Stevens’ production of The Greatest Story Ever Told. Starring Max von Sydow as Jesus Christ with an ensemble cast of actor favorites, the film was critically acclaimed and received five Academy Award nominations in 1965. However, the film recouped most though not all of its historic initial investment.

LATER DEVELOPMENTS and the end of an era.

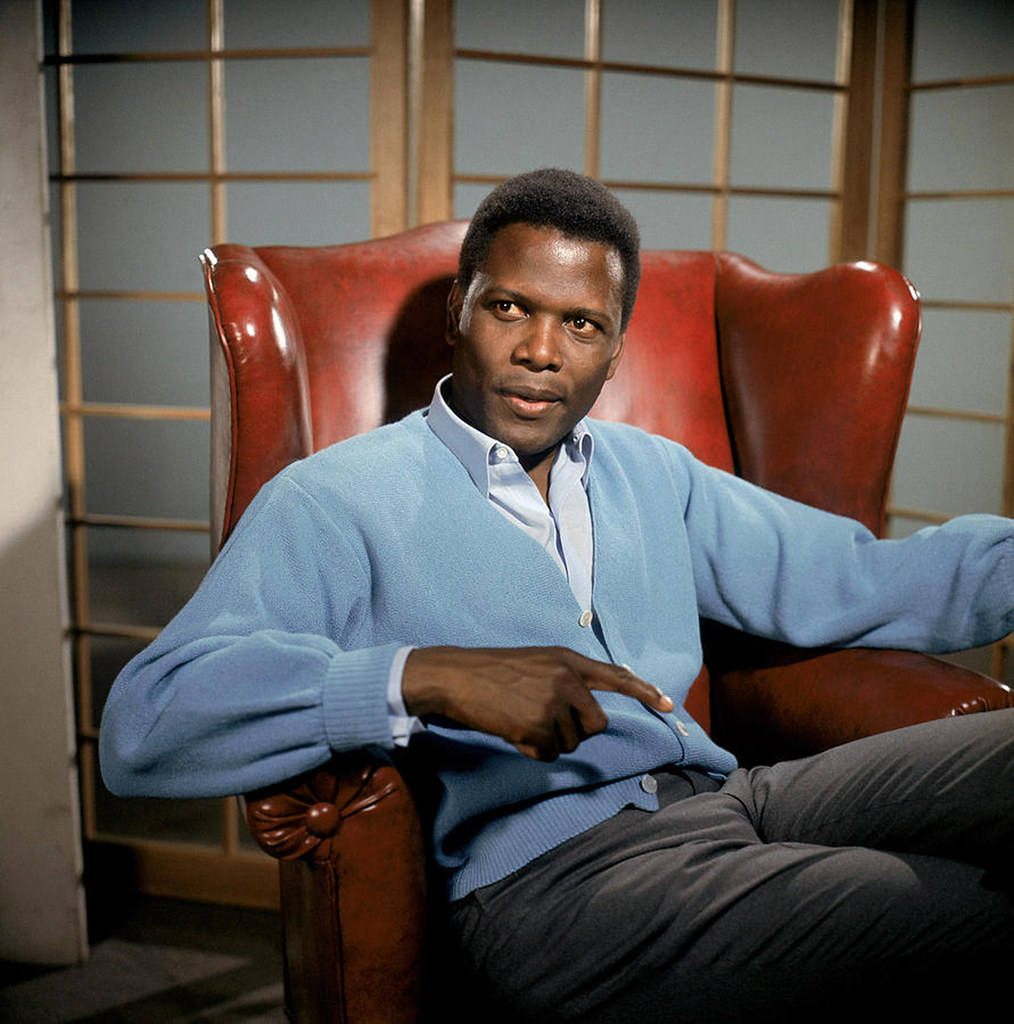

United Artists was ascendant in the 1960’s. It won 5 best Picture Oscars in the decade – more than any other single movie studio, a remarkable accomplishment. In addition to The Apartment in 1960 and West Side Story in 1961, there was Tom Jones directed by Tony Richardson in 1963, In the Heat of the Night in 1967, and Midnight Cowboy in 1969. United Artists was working with an array of directors such as Norman Jewison (In The Heat of the Night in 1967 and The Thomas Crown Affair in 1968), John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven in 1960), Robert Wise and Blake Edwards.15 In the 1960’s this diverse array of directors and actors and their films from United Artists found their audience although, as production exploded with independent projects, not every movie made its mark.16 Purchased in 1967 by Transamerica Corp. based on its film and television success, Krim and Benjamin were pushed aside for new management as UA continued to manufacture film hits such as The Graduate (Best Picture nominee) and In The Heat of the Night (Best Actor and Best Picture winner). In 1968 UA’s income reached $250 million with a $20 million in profit. Yet, in 1970, the studio lost $35 million. Krim and Benjamin were restored while staff and overhead expenses drastically cut.17

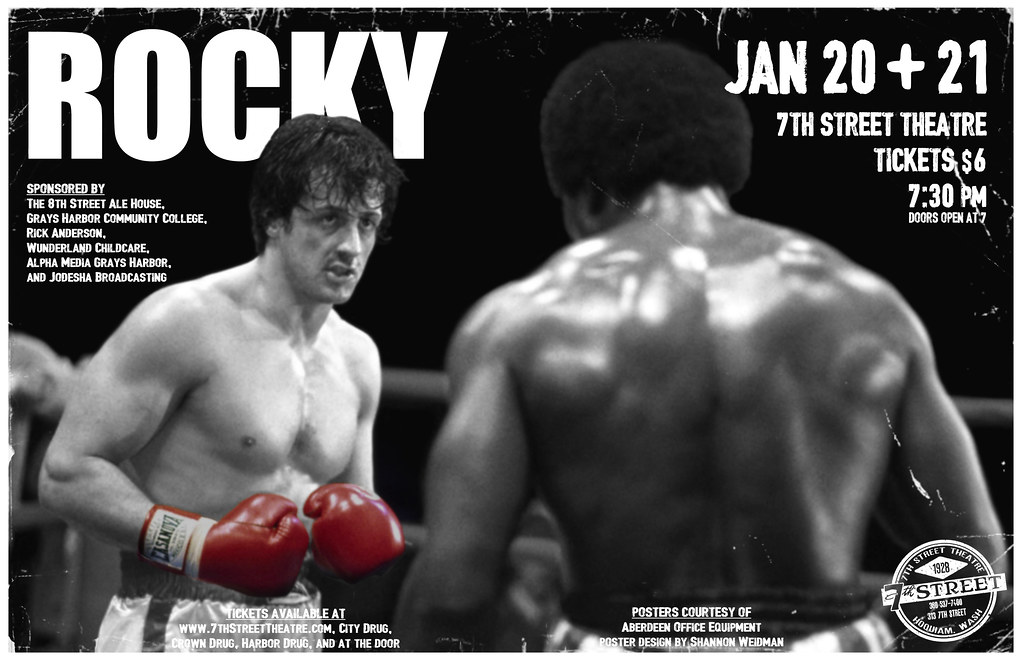

The decade of the 1960’s saw a precipitous decline in movie attendance. What began in 1960 with 44 million Americans, or 25% of the population, going to cinema each week was 15 million in 1970 – or less than 10%. Most of these numbers were concentrated in a few films while the rest languished. The movie studios’ search for the surefire blockbuster intensified. One or two misses could – and did – sink a studio’s fortunes. Though UA was no longer the Oscar leader, the 1970’s was a mostly remarkable decade for United Artists. It made hits such as Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and the James Bond series with Roger Moore and had three Best Picture films in a row – One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Rocky (1976) and Annie Hall (1977).19 Significantly, in 1977 and 1979, respectively, Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford both passed away – and, with them, some of the last vestiges of old Hollywood.

In 1978, following Chaplin’s death, Krim and Benjamin left UA to form Orion Pictures, looking to make it a worthy heir to what United Artists had been. Their exit evolved with clashes with Transamerica since the insurance giant took over the movie studio in 1967. In 1973, as United Artists took over U.S. sales and distribution of MGM films and its music publishing business, in 1981 Transamerica sold United Artists and its film library to Tracinda Corp. Since Tracinda Corp. owned MGM, these two iconic film studio brands merged to become MGM/UA Entertainment Company with a host of subsidiaries.20

Mid-1970’s – Three Best Picture Oscars in a Row.

The end of the 1970s was profitable for UA. Though Krim and Benjamin were gone, UA was headed by Andy Albeck, Krim’s longtime assistant and the studio’s investments were reaping themselves handsomely at the box office – Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979), Bond installment Moonraker (1979) and Rocky II were all hits, Although Westerns had fallen out of favor, in 1978 UA fronted almost $8 million for Heaven’s Gate. Starting in the 1960’s the film market was gearing to younger audiences. This trend intensified so that in the late 1970s and early 1980s most films were targeted to teenagers.21 Heaven’s Gate became way over budget and then opened to devastatingly reviews. Albeck saw the train wreck that was coming. The film was released then pulled and re-released after severe editing but was a box office bomb, Albeck resigned and UA, despite its money-making releases, including For Your Eyes Only (1981), Rocky III (1982) and Yentl (1983) was sold to MGM and became MGM/UA Entertainment Corp.

“moonraker” by cdrummbks is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Late 20th century to today.

By 1983, MGM started selling UA assets such as its New York City headquarters as part of the consolidation process while in terms of film and television production the two jointly-owned studios under Kirk Kerlorian’s Tracinda Corp. were put in direct competition with one another. In March 1985 both studios went under one studio head, Alan Ladd, Jr.22 In March 1986,Ted Turner bought MGM/UA and renamed it MGM Entertainment Co. selling back the United Artists’ assets (about one third of the deal) to Tracinda Corp. Though it shared the same or similar assets, it was, from a transactional viewpoint, the end of the original United Artists and start of a new company.23

Later in 1986 Turner sold back MGM’s production and distribution assets to United Artists, retaining ownership of film libraries. United Artists was renamed MGM/UA Communications Company.24 In the 1990s United Artists (MGM/UA) traded hands from and back to Tracinda Corp and in the 2000s MGM folded UA into Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures though certain distributorship, branding, and copyrights could bear the United Artists name. In 2005, Comcast, Sony and partner banks bought United Artists and, its parent, MGM, and folded those operations into Sony. The era of mega-consolidation was well underway.25 In 2006, in a return to its roots as an artists’ film studio, actor Tom Cruise, producer Paula Wagner and MGM Studios created United Artists Entertainment LLC. In 2011 it was revealed that MGM bought United Artists whose brand name remains though the last films made under the United Artists banner was in 2009. 26

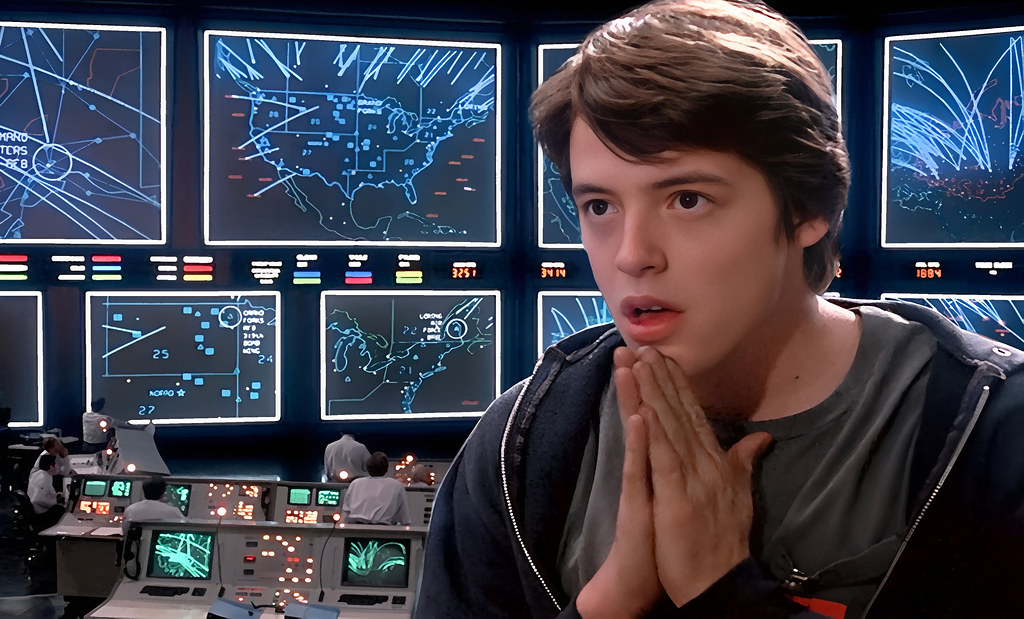

Since the 1980’s until today, certain UA films have been geared to mature audiences -such as, François Truffaut’s The Last Metro (1981), Karel Reisz’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), Walter Hill’s Wild Bill (1995) and other less successful ventures. But, starting with War Games (1983), the majority of feature films released in the last 40 years are geared to the youth market demographic.

Notes:

1. Bergan, Ronald, The United Artists Story, Crown, 1986, p. 8.

2. Ibid., p.8.

3. Ibid., p.6; see – https://www.movieinsider.com/m20828/the-underdoggs – retrieved August 8, 2023.).

4. see- Balio, Tino, United Artists, Volume 1, 1919–1950: The Company Built by the Stars, 2009 and Welsch, Tricia, Gloria Swanson: Ready for Her Close-Up, University Press of Mississippi, 2013.

5. The UA Story, p.41; https://web.archive.org/web/20220213144356/http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/metro-goldwyn-mayer-inc-history/ – retrieved 8.17.23.

6. The UA Story, p.41.

7. A Short History of The Movies, Gerald Mast, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis, 1977, p.263.

8. https://news.gallup.com/poll/388538/movie-theater-attendance-far-below-historical-norms.aspx – retrieved August 11, 2023.

9. The UA Story, p. 87.

10. Mast, p. 263 and https://news.gallup.com/poll/388538/movie-theater-attendance-far-below-historical-norms.aspx – retrieved August 11, 2023.

12. https://web.archive.org/web/20220213144356/http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/metro-goldwyn-mayer-inc-history/ – retrieved 8.17.23.

13. https://www.jewoftheweek.net/2019/04/10/jews-of-the-week-mathilde-and-arthur-krim/ – retrieved 8.17.23.

14. Mayer, Arthur L., “UA at 40,” Variety, June 24, 1959, p. 42; Balio, Tino (March 2, 2009). United Artists: The Company that Changed the Film Industry (1st ed.). Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 226–227.

15. The UA Story, p. 195.

16. Ibid., p. 231.

17. Ibid., p. 251.

19. The UA Story, p. 251.

20. https://web.archive.org/web/20220213144356/http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/metro-goldwyn-mayer-inc-history/ – retrieved 8.17.23. “Big 3 Sold to UA; Plus 1/2 Can. Co”. Billboard Magazine. October 27, 1973. p. 3. – retrieved August 8, 2023; Cole, Robert J. (May 16, 1981). “M-G-M is Reported Purchasing United Artists for $350 Million”. The New York Times, p.1 – retrieved August 8, 2023.

21. The UA Story, p. 293.

22. https://web.archive.org/web/20220213144356/http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/metro-goldwyn-mayer-inc-history/ – retrieved 8.17.23.

23. Balio, Tino (March 2, 2009). United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 343.

24. Gendel, Morgan (June 7, 1986). “Turner Sells The Studio, Holds on to the Dream”. Los Angeles Times – retrieved August 8, 2023; “Turner, United Artists Close Deal”. Orlando Sentinel. United Press International. August 27, 1986 – retrieved August 8, 2023.

25. Leming, Mike Jr; Busch, Anita (September 22, 2014). “MGM Buys 55% Of Roma Downey And Mark Burnett’s Empire; Relaunches United Artists”. Deadline Hollywood; “United Artists restructuring by MGM”. CNNMoney. June 7, 1999.

26. Fritz, Ben, “MGM regains full control of United Artists”. Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2012.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Short History of The Movies, Gerald Mast, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis, 1977.

Film Noir Guide, Michael F. Keaney, McFarland & Co., Inc. Jefferson North Carolina, 2003.

History of the American Cinema, Volume 5, 1930-1939, Charles Harpole, General Editor, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993.

Hollywood The Glamour Years (1919-1941), Robin Langley Sommer, Gallery Books: New York, 1987.

License To Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films, James Chapman, 2009.

My Autobiography, Charlie Chaplin, Melville House Publishing, Brooklyn and London, 2012 (originally published in 1964).

The American Film Industry, ed. Tino Balio, University of Wisconsin Press, 1976.

The United Artists Story, Ronald Bergan, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1986.

United Artists, Volume 1, 1919–1950: The Company Built by the Stars, Tino Balio, University of Wisconsin Press, 2009

United Artists, Volume 2, 1951–1978: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, Tino Balio, University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

You’re Only as Good as Your Next One: 100 Great Films, 100 Good Films, and 100 for Which I Should Be Shot, Mike Medavoy and Josh Young, New York: Pocket Books, 2002.