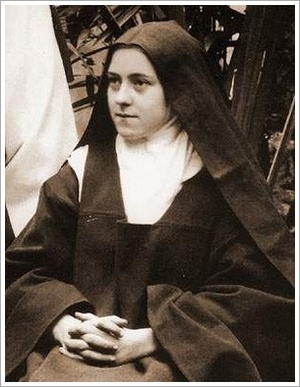

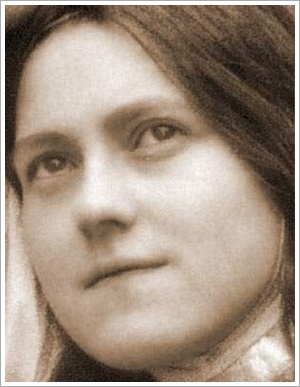

FEATURE image: Thérèse Martin (St. Thérèse of Lisieux) at 15 years old in a photograph taken in October 1887.

By John P. Walsh

October 1 is the feast day of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux (French, 1873-1897), one of only four women “doctors” in the Roman Catholic Church, and popularly known as The Little Flower of Jesus. Her religious name is Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face and, with St. Francis of Assisi, she is one of today’s most popular saints. For a young Norman woman who died at 24 years old in an obscure convent in northern France that is a surprisingly solid list of titles and accolades.

Yet, when she died on September 30, 1897, the Carmelite nuns in her community at the Carmel in Lisieux didn’t think they had any accomplishments to cite for her obituary. Her sister Céline (1869-1959), a nun in the same convent as Thérèse, observed: “In general, even in the last years, she continued to lead a hidden life, the sublimity of which was known more to God than to the Sisters around her.”1

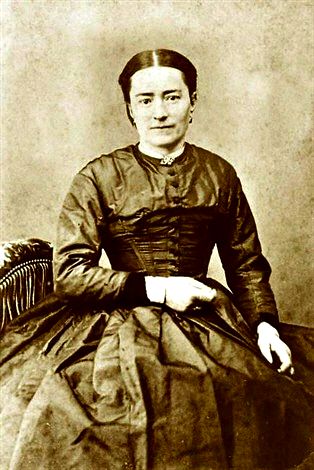

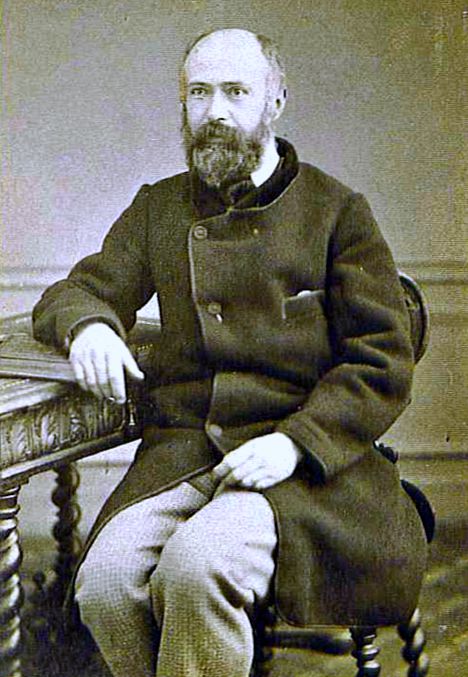

Born Marie-Françoise-Thérèse Martin in 1873, she was the youngest of five sisters and lively and precocious. She lost her mother Zélie Martin (née Guérin, 1831-1877) to breast cancer as a four-year-old. The next decade – according to Thérèse’s journal (The Story of a Soul, begun in 1895) – was the most “distressing” years of her life.2

Thérèse’s mother was the breadwinner in the Martin house and after she died little Thérèse naturally turned to her father Louis (1823-1894) for nurturing along with her four older sisters — especially the second eldest, Pauline.

For the rest of the 1870s and into the 1880s, Thérèse was the high-spirited baby sister in the family home called Les Buissonnets in the Normandy town of Lisieux.

As three of Thérèse’s sisters left the family homestead to enter convents -– two of them to a Carmelite convent (“Carmel”) in Lisieux and another later to a Visitation convent in Caen– the two youngest sisters, Céline and Thérèse, remained at home with their father.

Although Louis adored Thérèse and called her his “little flower,” Thérèse was headstrong and obstinate and she seemed to do chores with the attitude like she was doing the household a big favor. The young child also began to have panic attacks. Though intelligent and educated, at ten years old Thérèse believed she saw a statue of the Blessed Virgin given to her by her mother in her bedroom smile at her. While unusual, from that point forward, the girl’s nerves calmed. These early tantrums left a mark on her reputation. They, along with some of her later writings in journals, letters, and poems, left the future saint prey for others in her lifetime and after her death to be called “immature” and “sentimental,” even “neurotic.”3

Doubtless some of Thérèse’s thoughts sound naïve, though she writes profoundly: “At times when I am reading certain spiritual treatises in which perfection is shown through a thousand obstacles…my poor little mind quickly tires; I close the learned book that is breaking my head and drying up my heart and I take up Holy Scripture. Then all seems luminous to me; a single word uncovers for my soul infinite horizons, perfection seems simple to me, I see it is sufficient to recognize one’s nothingness and to abandon oneself as a child into God’s arms.”4

On April 9, 1888, a 15-year-old Thérèse entered the Carmel de Lisieux on Rue du Carmel, less than a one-half mile walk from Les Buissonnets. Younger than a typical postulant, exceptions had to be made. She received the habit after some delay mostly because of her father’s declining health in January 1890. Although her profession was also postponed, Thérèse’s spiritual life was deepening through her reading of another Carmelite, St. John of the Cross (1542-1591).

In due time, despite difficulty in prayer and doubts about becoming a nun, Thérèse received the black veil in September 1890. In early 1891 the 18-year-old Thérèse was made sacristan’s aide, a duty she carried into 1892 as her father lay slowly dying. During this time her reading and prayer transitioned to the Gospels and she began to write poems for which she had talent. Founded in 1838 as a “progressive” convent so that by the 1890’s the nuns were allowed to practice photography within its walls, the Carmel was also a working-class foundation comprised of daughters of shop-keepers and craftspeople brought up to expect a day’s work for a day’s wage. Thérèse, like another young French mystic saint, St. Bernadette Soubirous, sought to be useful.

When Thérèse’s favorite sister Pauline was elected prioress in early 1893, Thérèse was appointed novice master (though a novice herself) and embarked on her artistic avocation of picture painting. Scheduled to graduate from the novitiate in September 1893 it was postponed in part due to convent politics. The duty of doorkeeper’s aide was added to Thérèse’s tasks.

In the spring of 1894 Thérèse began to experience chest pains and a hoarse throat that grew worse by that summer. After her father died in July 1894, Céline entered the Carmel six weeks later. It was at that time that Thérèse began to seriously formulate her “little way” of seeking holiness of life based on scripture passages. Before 1894 had ended, her sister Pauline (Mother Agnes Of Jesus) ordered her to begin to record her life story in a journal (The Story of a Soul). The novice composed her journal in segments in her free time over the next two and a half years.

Early in 1895 Thérèse voiced the first prediction of her death as her prayer life was working out an idea for what she would dedicate her life to. It would be a life with God whom she called Merciful Love. On June 9, 1895, the Feast of the Holy Trinity, during Mass, Thérèse decided to offer herself to Merciful Love who is the Lord. Thérèse confided these spiritual developments to Céline so that by summer 1895 Thérèse recommended the same devotion to more nuns in the community.

Sister Geneviève recounted later in her memoirs: “Coming out of Mass, eyes all on fire, breathing holy enthusiasm, Thérèse dragged me without saying a word to follow our Mother who was then Mother Agnes of Jesus. She told him in front of me how she had just offered herself as a Holocaust Victim to Merciful Love, asking her permission to deliver us together. Our Mother, in a great hurry at the moment, allowed everything without really understanding what it was about. Once alone, Thérèse confided in me the grace she had received and began to compose an act of offering.” (”Au sortir de la messe, l’œil tout enflammé, respirant un saint enthousiasme, Thérèse m’entraîna sans mot dire à la suite de notre Mère qui était alors Mère Agnès de Jésus. Elle lui raconta devant moi comment elle venait de s’offrir en Victime d’Holocauste à l’Amour Miséricordieux, lui demandant la permission de nous livrer ensemble. Notre Mère, très pressée en ce moment, permit tout sans trop comprendre de quoi il s’agissait. Une fois seule, Thérèse me confia la grâce qu’elle avait reçue et se mit à composer un acte d’offrande.”)

Throughout 1895 Thérèse continued to write–composing poems and giving them as gifts on special occasions, writing plays and painting pictures. Her spirit was characterized by humility.

Thérèse wrote: “How shall she prove her love since love is proved by works? Well, the little child will strew flowers, she will perfume the royal throne with their sweet scents, and she will sing in her silvery tones the canticle of Love.”5 (the emphases are Thérèse’s).

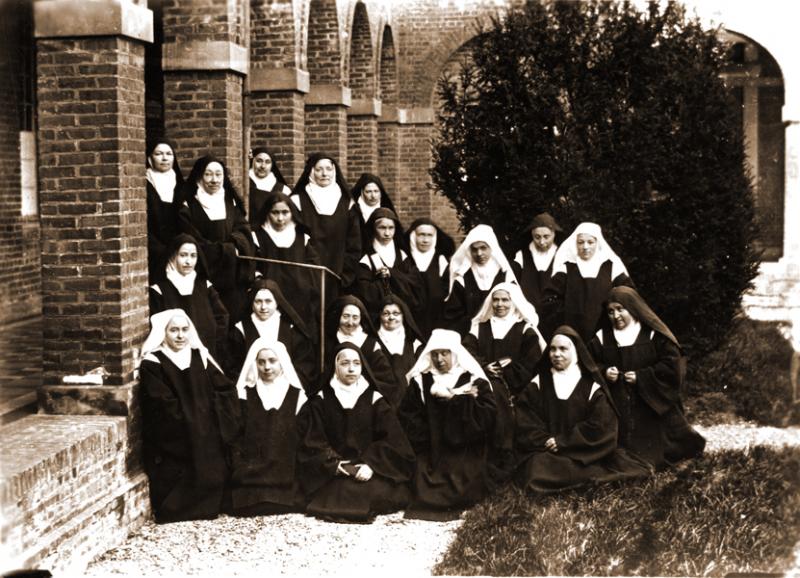

Above: Recent photograph of the Carmelite convent (Carmel) where Thérèse Martin entered at Lisieux in April 1888. Photograph of Carmel taken by Céline in September 1894 where Thérèse stands on the steps, third from the right.

Bishop Hugonin of Bayeux and Lisieux had confirmed Thérèse on June 14, 1884. Nearly four years later, he authorized, with some reluctance on account of her young age, Thérèse’s entrance in Carmel at 15 years old. Soon after, Bishop Hugonin presided over her clothing on January 10, 1889 as he showed continued solicitude for the young Carmelite novice he had specially approved. Less than two months before his own death in May 1898, Bishop Hugonin, on March 7, 1898, gave his verbal imprimatur to Thérèse’s Story of a Soul.

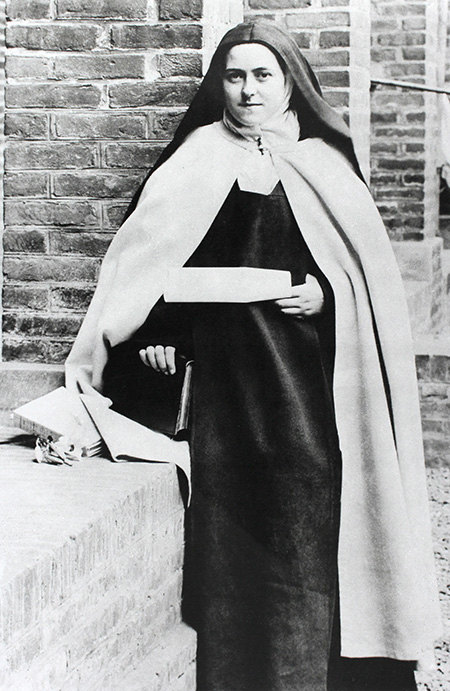

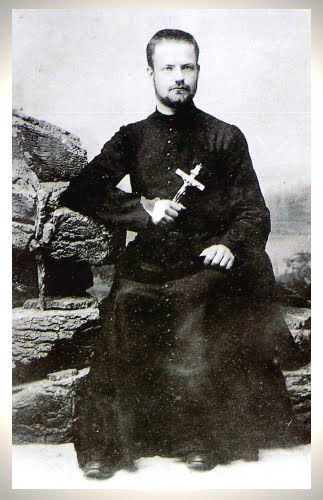

Two photographs above and one below: Thérèse as a novice in Carmel in a photograph taken in January 1889. She was 16 years old and in the convent nine months. The photographs were taken by Fr. Gombault, the bursar of the minor seminary.

A series of photographs taken by Céline from January 21 to March 25, 1895, in the convent courtyard. Thérèse is dressed as Joan of Arc who did not become a canonized saint until 1920. Thérèse played the part of La Pucelle in a play Thérèse had written called Joan of Arc Accomplishing Her Mission.

A longtime revered figure in France Joan of Arc was not yet a canonized saint in late winter 1895 when 22-year-old Thérèse dressed as her for a play within the convent walls and was photographed by her older sister Céline. Joan of Arc became a canonized saint following World War I on May 16, 1920.

Between January and March 1895 Thérèse chose to dramatize Joan of Arc who is today one of the patron saints of France. In the 15th century Joan became an unrelenting vessel of combat and action for the French King—and was burned at the stake by her enemies in Rouen, France, at the incredibly young age of 19 years old. Joan’s mission on earth always was driven by a spiritual dimension (her “voices”). About her dressing in armor, Joan said: “What concerns this dress is a small thing – less than nothing. I did not take it by the advice of any man in the world. I did not take this dress or do anything but by the command of Our Lord and of the Angels.”

In March 1895 Thérèse was 22 years old. In a little over a year Thérèse’s symptoms of tuberculosis indicated a serious turn for the worse in her health. Over the next two years, her health continued to decline so that by summer 1897 Thérèse was on her death bed.

Thérèse knew her great desire to be a missionary to Vietnam was now impractical. In June 1895 Thérèse decided to have an earthly mission within convent walls of “merciful love” and the “little way.” Like young Joan of Arc, Thérèse’s spiritual mission began on earth and would continue in heaven. So that a little over 6 months before her early death at 24 years old, Thérèse implored the favor by the command of Our Lord and of the Angels of “spending her heaven doing good on earth.”

Easter Monday, April 15, 1895.

Photograph taken by Céline for the feast of the Good Shepherd, April 27 or 28, 1895. Thérèse is at right between two of her white-veiled novices.

Above photograph (including close-up) was taken by Céline in July 1896. Thérèse had been ill for several months.

After July 3, 1896, photograph taken by Céline.

Thérèse holds a lily in a photograph taken by Céline in the convent garden in July 1896.

Photograph of the community taken by Céline. July 1896.

FRENCH:

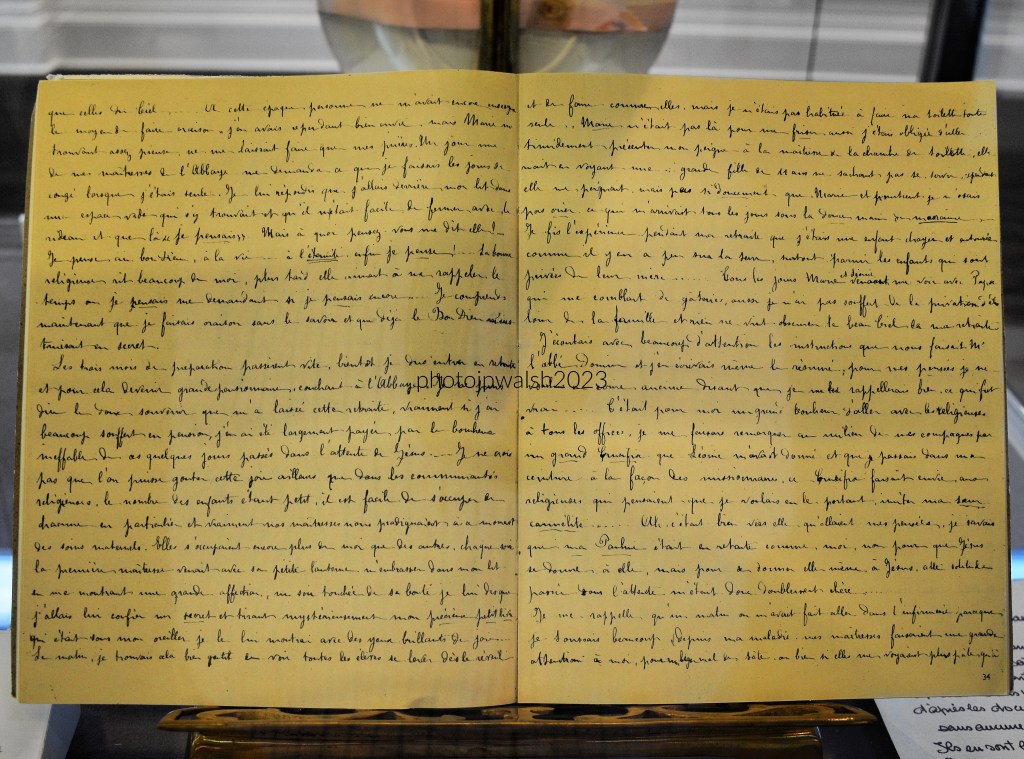

A cette époque, il m’eût été bien doux de faire oraison; mais Marie, me trouvant assez pieuse, ne me permettait que mes seules prières vocales. Un jour, à l’Abbaye, une de mes maîtresses me demanda quelles étaient mes occupations les jours de congé, quand je restais aux Buissonnets. Je répondis timidement: «Madame, je vais bien souvent me cacher dans un petit espace vide de ma chambre, qu’il m’est facile de fermer avec les rideaux de mon lit, et là, je pense…—Mais à quoi pensez-vous? me dit en riant la bonne religieuse.—Je pense au bon Dieu, à la rapidité de la vie, à l’éternité; enfin, je pense!» Cette réflexion ne fut pas perdue, et plus tard ma maîtresse aimait à me rappeler le temps où je pensais, me demandant si je pensais encore… Je comprends aujourd’hui que je faisais alors une véritable oraison, dans laquelle le divin Maître instruisait doucement mon cœur.

Les trois mois de préparation à ma première communion passèrent vite; bientôt je dus entrer en retraite et pendant ce temps devenir grande pensionnaire. Ah! quelle retraite bénie! Je ne crois pas que l’on puisse goûter une semblable joie ailleurs que dans les communautés religieuses: le nombre des enfants étant petit, il est d’autant plus facile de s’occuper de chacune. Oui, je l’écris avec une reconnaissance filiale: nos maîtresses de l’Abbaye nous prodiguaient alors des soins vraiment maternels. Je ne sais pour quel motif, mais je m’apercevais bien qu’elles veillaient plus encore sur moi que sur mes compagnes. Chaque soir, la première maîtresse venait avec sa petite lanterne ouvrir doucement les rideaux de mon lit, et déposait sur mon front un tendre baiser. Elle me témoignait tant d’affection, que, touchée de sa bonté, je lui dis un soir: «O Madame, je vous aime bien, aussi je vais vous confier un grand secret.» Tirant alors mystérieusement le précieux petit livre du Carmel, caché sous mon oreiller, je le lui montrai avec des yeux brillants de joie. Elle l’ouvrit bien délicatement, le feuilleta avec attention et me fit remarquer combien j’étais privilégiée. Plusieurs fois, en effet, pendant ma retraite, je fis l’expérience que bien peu d’enfants, comme moi privées de leur mère, sont aussi choyées que je l’étais à cet âge.

J’écoutais avec beaucoup d’attention les instructions données par M. l’abbé Domin, et j’en faisais soigneusement le résumé. Pour mes pensées, je ne voulus en écrire aucune, disant que je me les rappellerais bien; ce qui fut vrai. Avec quel bonheur je me rendais à tous les offices comme les religieuses! Je me faisais remarquer au milieu de mes petites compagnes par un grand crucifix donné par ma chère Léonie; je le passais dans ma ceinture à la façon des missionnaires, et l’on crut que je voulais imiter ainsi ma sœur carmélite. C’était bien vers elle, en effet, que s’envolaient souvent mes pensées et mon cœur! Je la savais en retraite aussi; non pas, il est vrai, pour que Jésus se donnât à elle, mais pour se donner elle-même tout entière à Jésus, et cela le jour même de ma première communion. Cette solitude passée dans l’attente me fut donc doublement chère.

Enfin le beau jour entre tous les jours de la vie se leva pour moi! Quels ineffables souvenirs laissèrent dans mon âme les moindres détails de ces heures du ciel! Le joyeux réveil de l’aurore, les baisers respectueux et tendres des maîtresses et des grandes compagnes, la chambre de toilette remplie de flocons neigeux, dont chaque enfant se voyait revêtue à son tour; surtout l’entrée à la chapelle et le chant du cantique matinal: O saint autel qu’environnent les anges!*

see HISTOIRE D’UNE AME – https://www.gutenberg.org/files/36708/36708-h/36708-h.htm

Circumstances were growing more difficult for Thérèse in terms of her health and spirituality. In 1896 a new prioress of Carmel confirmed Thérèse’s role in the novitiate where she could continue to teach her “little way” and work in the sacristy and the laundry room. In addition to finding it difficult to pray, in April 1896 she began to spit blood, a sure sign of the seriousness of her illness. These last eighteen months of her life proved a dark period for the normally vivacious five-foot three-inch Norman young woman. Her physical pain was often unrelenting and the dreams she had of becoming a foreign missionary to Vietnam had to be abandoned. Yet, the priest in charge of foreign missions, Father Adolphe Roulland (1870–1934) whom Thérèse had met in July 1896 as he was going to China, asked her to be a “spiritual sister” to the mission priests. This charge meant not only to pray for the priests but in her correspondence with them to “console and warn, encourage and praise, answer questions, offer corroboration, and instruct them in the meaning of her little way.”6

In a letter from Thérèse to Fr. Roulland she wrote: “Reverend Father… I feel very unworthy to be associated in a special way with one of the missionaries of our adorable Jesus, but since obedience entrusts me with this sweet task, I am assured my heavenly Spouse will make up for my feeble merits (upon which I in no way rely), and that He will listen to the desires of my soul by rendering fruitful your apostolate. I shall be truly happy to work with you for the salvation of souls. It is for this purpose I became a Carmelite nun; being unable to be an active missionary, I wanted to be one through love and penance just like Saint Teresa, my seraphic Mother….I beg you, Reverend Father, ask for me from Jesus, on the day He deigns for the first time to descend from heaven at your voice, ask Him to set me on fire with His Love so that I may enkindle it in hearts. For a long time I wanted to know an Apostle who would pronounce my name at the holy altar on the day of his first Mass….I wanted to prepare for him the sacred linens and the white host destined to veil the King of heaven…The God of Goodness has willed to realize my dream and to show me once again how pleased He is to grant the desires of souls who love Him alone.”7

The year 1897 was defined on the one hand by Thérèse’s physical decline because of tuberculosis and, on the other hand, her personal joy expressed in her conversations and poems. It was on the feast day of St. Joseph, March 19, 1897, during a personal novena to St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), that Thérèse asked St. Joseph to obtain from God the favor of “spending her heaven doing good on earth.” She asked St. Francis Xavier for the same intercession.8

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682), St. Joseph and the Child Jesus, Glasgow.

St. Francis Xavier baptizing, 18th century, Mexico City.

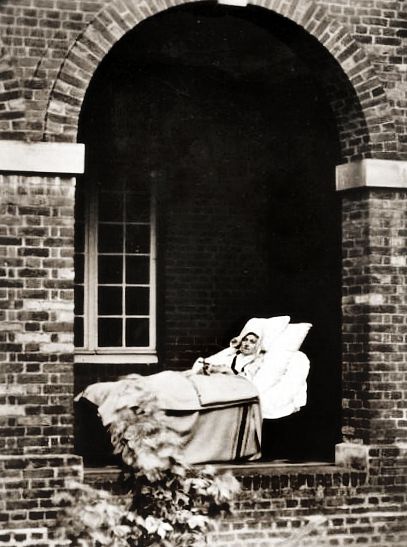

By April 1897 Thérèse was gravely ill and in May 1897 was relieved of all work duties and community prayer. Thérèse continued to write in her journal but abadoned it, too weak to write. In August 1897 Thérèse’s suffering was so great she confessed to the temptation of suicide. After August 19, 1897 Thérèse was too physically weak to even ingest the consecrated communion wafer. On September 30, 1897, Thérèse died in the convent infirmary. She was 24 years old.

In her last hours Thérèse said: “Oh! It is pure suffering because there are no consolations. No, not one! O my God…Good Blessed Virgin, come to my aid! My God…have pity on me! I can’t take it anymore! I can’t take it anymore!…I am reduced…No, I would never have believed one could suffer so much…never! never!…I no longer believe in death for me…I believe in suffering…O I love Him. My God I love you…”9 These last words of the dying nun were reported by more than one witness.

At the centenary of her death in 1997, St. Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) made Thérèse a “Doctor of the Church,” one of only thirty-three such credentialed. By elevating Thérèse’s example of simple love, the Polish pope, himself called out from behind an Iron Curtain and lived to see it fall, clarified what may constitute a Church Doctor’s character and purpose.

St. Thérèse of Lisieux was beatified on April 29, 1923 and canonized on May 17, 1925. She is co-patron saint of all church missions with St. Francis Xavier and co-patron saint of France with St. Jeanne d’Arc (1412-1431). Thérèse is patron saint of AIDS sufferers, pilots, florists, bodily ills (particularly tuberculosis), and the loss of parents.

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux’s obituary was written by the nuns of her community and printed in Le Normand. In an English translation it reads:

“It is with a spirited feeling of sadness that we learned Thursday evening of the death at the Monastery of Our Lady of Mount Carmel of a young person who gave the most beautiful years of youth to a life of prayer and sacrifice. Miss Marie-Francoise-Thérèse Martin, renounced the world at fifteen years of age and consecrated herself to God as Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus. She departed after ten years of angelic life in the shadow of the cloister, and we have sweet confidence that death which put an end to long and cruel sufferings has come to take this youth in her bloom and already placed on her head the immortal crown, the goal of all our earthly aspirations. The funeral will be celebrated Monday morning at 9 o’clock in the Carmel chapel. Le Normand offers to the family of Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus and to the Prioress and all the Carmelite sisters the tribute of its respectful condolences.”

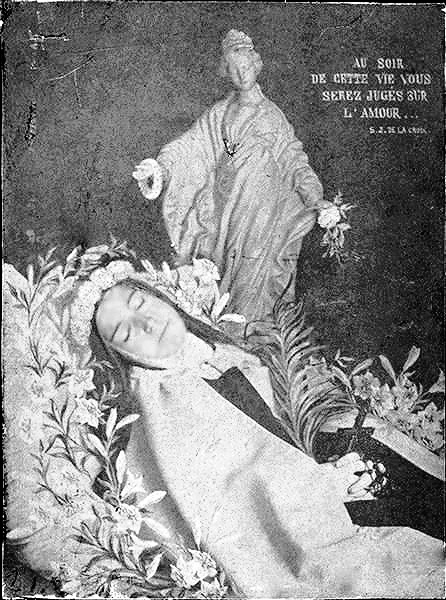

Thérèse died in the evening of September 30, 1897. The next morning, October 1, 1897, before her body left the infirmary where she died, Céline (Sister Geneviève), deeply impressed by Thérèse’s peaceful countenance in death, took one final photograph of her sister.

Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus was buried in the Carmelite section at the municipal cemetery at Lisieux on the morning of October 4, 1897 after a funeral Mass at the Carmel. An obscure figure at the time of her death, the funeral procession which followed her body to the cemetery was small that day. It was to this municipal cemetery grave that pilgrims first came. Miracles began to be reported to have taken place at her tomb through her intercession. One notable miracle was that of Reine Fauquet, a four-year-old girl from Lisieux, who was blind. On May 25, 1908, the child was brought by her mother to the tomb of Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus where the child’s sight was suddenly restored. A medical doctor who was not in favor of making Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus a saint, signed the medical documents attesting to the cure.10

Because of these events, a tribunal was convened by the bishop of Bayeux in August 1910 to interview witnesses at Lisieux. To investigate the corporeal remains of Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus for its condition, the body was exhumed on September 6, 1910. The exhumation took place in the presence of the bishop of Bayeux, Thomas-Paul-Henri Lemonnier (1853-1927) and scores of others. The doctors who treated Thérèse before her death confirmed that the body decayed in the usual manner, finding only bones and bits of clothes.

The site of Therese’s first grave from 1897 to 1910 continues to be marked by the same cross. The site of her second grave in the same Carmelite section of the municipal cemetery is also marked. The second grave held her bodily remains in a cemented vault from 1910 until 1923. When Sister Thérèse of the Child jesus was declared a “servant of God,” the first step on the road to sainthood, there was a second exhumation. It was to the second grave site that large and growing numbers of pilgrims came to implore the Little Flower’s intercessions. The cross that marked the second grave was completely covered by prayers and tributes to Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus by pilgrims.

On the occasion of her beatification, Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus’s remains were transferred for a third time on March 26, 1923 to the Carmelite Chapel at Lisieux. Saint Thérèse was canonized on May 17, 1925 by Pope Pius XI and declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope John Paul II in 1997. Her feast day is October 1.

It is recorded that on May 26, 1908, Reine Fauquet who lived in Lisieux was cured of an eye disease following her visit to Thérèse’s grave in Lisieux. The 4-year-old child explained to her sister that she had an apparition of Thérèse: “I saw little Thérèse, right next to my bed, she took my hand, she laughed at me, she was beautiful, she had a veil, and it was all lit around her head” (“J’ai vu la petite Thérèse, là, tout près de mon lit, elle m’a pris la main, elle me riait, elle était belle, elle avait un voile, et c’était tout allumé autour de sa tête“). When Reine Fauquet met Thérèse’s sisters at the Carmel they asked her how Thérèse had been dressed in the vision. The child replied: “The same as you!′′ (“Pareille à vous!“).

crèche.

On the evening of December 25, 1895, Thérèse created a ceremony for her community of sisters that celebrated the birthday of the Christ Child.

During the celebration each sister selected a folded note from a basket and handed it to an “angel” (one of the other sisters). The “angel” opened the note and sang its prayerful verse.

Each sister was then asked to offer to Jesus her best self in the coming year. Thérèse’s ceremony included a crib and wax figure of the infant Jesus for which Thérèse and her novice designed these hand-made costumes. A light-blue dress with lace trim was on display at the National Shrine of St. Thérèse in Darien, Illinois, in spring 2018. Photograph by the author.

The papal decree of August 14, 1921 declaring Thérèse of the Child Jesus a “Venerable” of the Church. It was promulgated by Benedict XV.

ENDNOTES:

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux: her last conversations, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1977, pp. 18-19. Her complete obituary printed in Le Normand reads: “It is with a spirited feeling of sadness that we learned Thursday evening of the death at the Monastery of Our Lady of Mount Carmel of a young person who gave the most beautiful years of youth to a life of prayer and sacrifice. Miss Marie-Francoise-Thérèse Martin, renounced the world at fifteen years of age and consecrated herself to God as Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus. She departed after ten years of angelic life in the shadow of the cloister, and we have sweet confidence that death which put an end to long and cruel sufferings has come to take this youth in her bloom and already placed on her head the immortal crown, the goal of all our earthly aspirations. The funeral will be celebrated Monday morning at 9 o’clock in the Carmel chapel. Le Normand offers to the family of Sister Thérèse of the Child Jesus and to the Prioress and all the Carmelite sisters the tribute of its respectful condolences.”

- see Story of a Soul: the Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1996, pp. 51-67.

- The Hidden Face: A Study of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Ida Friederike Görres, London, 2003, p. 83.

- Letter from Thérèse to Father Roulland, LT 226, dated May 9, 1897, Letters of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Volume II, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1974, p. 1094.

- Story of a Soul, p. 196. For this paragraph’s chronology see Letters of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Volume II, 1297-1329.

- Görres, p.189.

- Letter from Thérèse to Father Roulland, LT 189, dated June 23, 1896, Letters of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Volume II, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1974, pp. 956-957.

- see footnote 11 in Letters of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Volume II, p. 1074.

- Last conversations, pp. 204-205; 230; 243.

- Thérèse and Lisieux, Pierre Descouvement and Helmut-Nils Loose, Toronto: Novalis, 1996, p. 316.

*At that time, it would have been very sweet for me to make prayers; but Mary, finding me quite pious, allowed me only my vocal prayers. One day, at the Abbey, one of my mistresses asked me what my occupations were on my days off, when I stayed at Les Buissonnets. I replied timidly: “Madam, I often go to hide in a small empty space in my room, which it is easy for me to close with the curtains of my bed, and there, I think…—But what are you thinking? said the good nun, laughing.—I think of God, of the rapidity of life, of eternity; well, I think!” This reflection was not lost, and later my mistress liked to remind me of the time when I thought, asking me if I still thought… I understand today that I was then making a true prayer, in which the divine Master gently instructed my heart.

The three months of preparation for my First Communion passed quickly; Soon I had to retire and during this time become a boarder. Ah! What a blessed retreat! I do not believe that one can taste such joy anywhere else than in religious communities: the number of children being small, it is all the easier to take care of each one. Yes, I write it with filial gratitude: our mistresses of the Abbey then provided us with truly maternal care. I do not know for what reason, but I could see that they watched over me even more than my companions. Every evening, the first mistress came with her little lantern gently to open the curtains of my bed, and placed on my forehead a tender kiss.

I listened very carefully to the instructions given by Father Domin, and I carefully summarized them. For my thoughts, I would not write any, saying that I would remember them well; which was true. With what happiness I went to all the services like the nuns! I was noticed in the midst of my little companions by a large crucifix given by my dear Léonie; I put it in my belt like missionaries, and it was thought that I wanted to imitate my Carmelite sister in this way. It was to her, indeed, that my thoughts and my heart often flew away! I knew she was retired too; not, it is true, so that Jesus might give himself to her, but to give herself entirely to Jesus, and that on the very day of my First Communion. This solitude spent waiting was therefore

At last the beautiful day between all the days of life dawned for me! What ineffable memories left in my soul the smallest details of those hours of heaven! The joyful awakening of dawn, the respectful and tender kisses of mistresses and great companions, the washroom filled with snowflakes, with which each child saw himself clothed in turn; especially the entrance to the chapel and the singing of the morning hymn: O holy altar that surrounds the angels!

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Story of a Soul: the Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1996;

Light of the Night: The Last Eighteen Months in the Life of Thérèse of Lisieux, Jean-François Six, University of Notre Dame Press, South Bend, Indiana, 1996;

St. Thérèse of Lisieux: her last conversations, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1977;

Letters of St. Thérèse of Lisieux,Volumes I and II, translated by John Clarke O.C.D., ICS Publications, Institute of Carmelite Studies, Washington, D.C., 1974;

The Hidden Face: A Study of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Ida Friederike Görres, London, 2003;

http://floscarmelivitisflorigera.blogspot.com/2010/06/praying-for-priests-with-st-therese.html.

http://www.archives-carmel-lisieux.fr/

May I use some of your photos for a publication I am creating for the National Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, MI?