https://johnpwalshblog.com/2022/12/07/french-art-in-the-17th-century-simon-vouet-1590-1649/

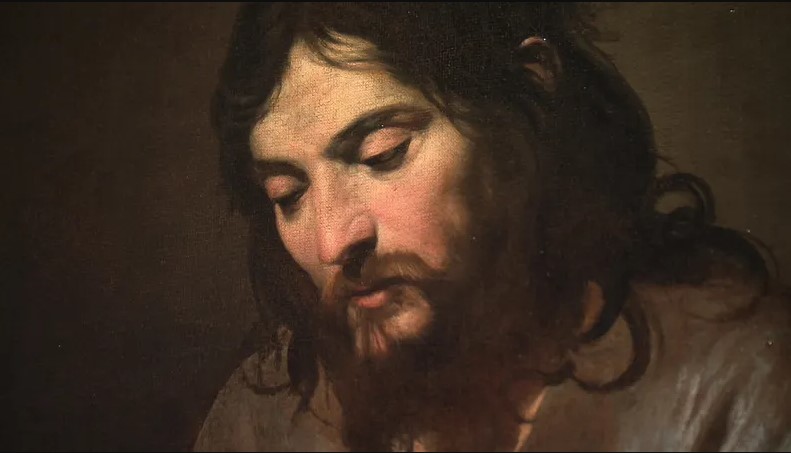

FEATURE Image: Simon Vouet (1590-1649), Self-portrait, c. 1626–1627, Musée des Beaux-arts de Lyon. https://www.mba-lyon.fr/fr/article/simon-vouet In Simon Vouet’s self portrait painted in his final years in Rome he displays his signature rapid brushwork and desire for movement in the picture.

Simon Vouet was born into modest circumstances in Paris on January 9, 1590. After stays in England in 1604, Constantinople in 1611 and Venice in 1613 of which little is known, the French painter Simon Vouet (1590-1649) spent nearly 15 years in Rome starting around 1614. In 1624 Vouet was elected to lead the Accademia di San Luca, an artists’ association founded in 1593 by Federico Zuccari (1539-1609).

Most French painters born in the 1590s made a stay in Rome which influenced art in France in the 17th century. Vouet was in Italy, primarily in Rome, between around 1613 until 1627 and received a special privilege from the French crown in 1617. It was this traffic of young French, Flemish and other international artists between Italy and their home countries in the first third of the 17th century that, for France, helped revolutionize French art. This was achieved by way of the contemporary application of ideas and styles influenced by late Renaissance Italian realist artists such as the aesthetic of Caravaggio (1571-1610) and the history painting method of Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), among many others, to which French artists were exposed while in Italy. In Rome Vouet, like other French artists such as Valentin de Boulogne (1591-1632), was patronized by Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597-1679) and Cavaliere del Pozzo (1588-1657), among others. In 1624 Vouet was commissioned to paint the fresco to accompany Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s and while greatly admired it was destroyed in the 18th century.

In addition to Rome, Vouet traveled to Naples, Genoa in 1620 and 1621, and, in 1627, Modena, Florence, Parma, Milan, Piancenza, Bologna and again Venice where he copied Titian (1488-1576), Tintoretto (1518-1594) and Paolo Veronese (1528-1588). During these visits Vouet studied the chief art collections that informed Vouet’s own style which amounted to a free form of temperate, classicized Baroque. This is the style, along with the latest Venetian-influenced brighter colors, vivid light, and painterly execution that Vouet returned and introduced to France in the 1630s. In France, Vouet had taken to himself as a painter his particular appreciation for the classicized compositions of Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) and the cool colors of Philippe de Champaigne (1602-1674).

In 1627, King Louis XIII (1601-1643) called Vouet back to Paris to be his court painter. Vouet refined Caravaggio’s innovations into a style that would become the French school of painting starting in the 1630s and extending into the middle of the 18th century. Until about 1630 it was Late Mannerism which dominated in French painting and included unnatural physiognomy, strained poses, and untenable draperies. This changed with Vouet’s return who brought back from Italy a style with classical, realist, and Baroque painting components that was unknown in France until then and which Vouet stamped with his own style.

This painting entered the Louvre as a work of the Neapolitan school. It was recent scholarship that attributed it to Vouet which would make it one of his earliest portraits in Rome. Building on the premise, scholars have proposed Francesco Maria Maringhi (1593-1653), a Florentine patrician and lover and protector of Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), as the model.

Vouet married twice. His first wife was a young Italian woman he met in 1625 – Virginia da Vezzo (1600–1638). In France Vouet’s wife, who bore him 4 children, was well received by the French court. After Virginia died in 1638, Vouet married Radegonde Béranger (b. 1615), a young beauty from Paris, in July 1640. Radegonde bore Vouet another 3 children (one died in infancy), and survived him.

The Birth of the Virgin was one of many paintings in a somber palette that Vouet produced in Rome influenced by Caravaggio though its mood is more vibrant. The composition is broad, low and somewhat setback from the picture plane. Amidst the swirling movement and vitality of the drawing and figures, including sumptuous draperies, it is observed that the head of the maid servant in the middle of the composition is modeled on one by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). These early qualities that Vouet had taken from Italian painting were, when he returned to France, taken over by a heightened decorative style in the 1630s and 1640s.

In Rome Simon Vouet adopted a Caravaggesque style coupled with elements from Michelangelo such as in this painting for an ancient church in Rome. While Vouet worked directly from the model and used closely observed poses from reality, the head of St. Francis of Assisi seems to be taken from one by Michelangelo. see –https://www.finestresullarte.info/en/works-and-artists/-almost-as-unbelievable-as-a-church-painting–simon-vouet-and-his-saint-francis-tempted

As Vouet stayed in Italy he increasingly turned to a Baroque style of which The Crucifixion with Mary and John in Genoa is an early example. The Appearance of the Virgin to St. Bruno in the Carthusian monastery of San Martino in Naples is a later and more fully realized Baroque style example. The atmosphere of each showing saints in ecstasy is a clear element in Baroque’s intensified and elaborated religious representation. In Italy Vouet’s paintings are more restrained than the full contemporary Baroque art of Pietro da Cortona (1597-1669) and his followers such that the French painter’s figure of the Virgin in his Naples’ picture tends towards a classical Renaissance tradition that would be an important part of the expression of French taste in the 1630s and 1640s.

The painting by Vouet towards the end of his Roman period, the identity of the young man above is unknown though speculation by modern scholars is impressive (i.e., St. Thomas Aquinas, among others). The painting’s copies are numerous which points to the composition’s success. These copies can be found in major museums throughout Europe.

In 1627 Vouet painted Saint Jerome and the Angel featuring an elderly bearded saint and a winged curly-haired angel holding a trumpet that signifies the Last Judgment. While the composition is Caravaggesque in its naturalistic depiction of half figures, stark lighting, and dark-brown palette, Vouet’s painting features brighter colors in the robes and clothes which was a departure from the Caravaggesque tradition and, among some contemporary artists in Rome in the late 1620s, an aesthetic innovation. The painting demonstrates Vouet’s superb fluid handling of paint which he brought back to and deployed in France starting in the 1630s.

Vouet was a leading French artist in Rome when asked to return to France by the king in 1627. At his arrival, though embraced by King Louis XIII and his mother, Marie de’ Medici, Vouet was kept at a distance by Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) who viewed the ambitious artist as a social climber. Though modest compared to the great collections in London and Madrid, Cardinal Richelieu collected about 272 pictures, the canvasses listed in an inventory compiled by Vouet and his student, Laurent de la Hyre. Though Richelieu succeeded in getting Poussin to return to France from Rome in 1641and as “First Painter,” this direct competition to Vouet was short-lived. Richelieu died in 1642 and Poussin left for Italy the same year.

The king set Vouet to the task of painting portraits of the court nobility though just one survives today – that of Richelieu’s secretary. In 1648, when the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture was established – an organization that held monopoly power over the arts in France for the next 150 years – Vouet was not invited to join. Vouet understood that the academy, which included his pupils Le Brun and Le Sueur, was established in part as a generational shift that challenged his influence and authority. Vouet countered by modernizing the old painter’s guild but did not live to see the battle joined. He died of exhaustion in June 1649. The Academy went on to school artists, provide access to prestigious commissions, and hosted the Salon to exhibit their work. After Vouet’s death, the Académie soon rose to prominence with Jean-Baptiste Colbert, First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under Louis XIV, as its protector and Charles Le Brun as First Painter and the Académie’s director.

Upon Vouet’s return to France in late November 1627, his French style set to work mainly on religious subjects which were admired by the public, particularly in diocesan and religious orders’ churches of Paris. As late as 1630, the eye of the Paris art consumer was used to prevailing late 16th century mannerism. It took time for the French to better accept Vouet’s new Caravaggesque naturalism. Further, while France was a so-called eldest daughter of the Catholic Church, Parisians did not share the intense religious enthusiasm that was the art expression in the papal states. Parisians did not fully accept the swirling heavenly masses found in Italian Baroque. In France Vouet had to temper his stylistic synthesis of classicism, naturalism and baroque as the French expression of and contribution to a great international style.

Vouet’s new and tempered French style is exquisitely represented in Madonna and Child (1633). During the religious reformation period in the 16th century one of the Catholic Church’s responses was the renewal of devotion to the Virgin Mary. This cult of the Virgin, once blossomed in the 12th century, was in renewed full maturity in the 1630s and even inspired the French king to dedicate his North American empire to her in 1638. Vouet painted more than a dozen compositions of the Virgin and her son at half-length. While the blank background and figurative monumentality remain from his Roman days, Vouet’s mastery of light and use of bright colors signal the realization of the new French style. The monumental figure of the seated Virgin depicted in a Mannerist and Classical synthesis holds her son on her lap and looks at him with drooping eyes.Her arm supported by the foundation of a classical column, Mary’s dark hair is held back by a fabric band as her neck and shoulder are exposed. The Christ child reaches up to kiss his mother, his body in a Baroque twist as he caresses her face. The brilliantly executed moment expresses intimacy and tenderness while maintaining religious seriousness.

The Bible story of depravity that Vouet depicts is that of Lot and his daughters found in Genesis 19. The angels have warned Lot who is an upright man that Sodom and Gomorrah are to be destroyed for its sins. As Lot’s family escapes, they are warned not to look back on the Divine destruction. Lot’s wife disobeys and is turned into a pillar of salt. Despairing of finding husbands where they are going and so carry on their own people, Lot’s daughters devise to get their father drunk and lie with him. Both daughters become pregnant in this way.

Vouet depicts Lot of the Old Testament story as they break the taboo of incest to carry on the race in desperate times using Renaissance artistic language of a god from pagan mythology. In place of moralizing, Vouet composes a sensual scene showing Lot, a male figure of late middle age, tasting the company of two nymph-like young women in a canvas filled with the attraction of the flesh and drunken debauchery. The lines and forms of Vouet’s new painting give priority to its narrative power which will be the manner of his artwork following his return to France. It is noted that Vouet used a contemporary engraving of an ancient relief to model the figure of the seated daughter.

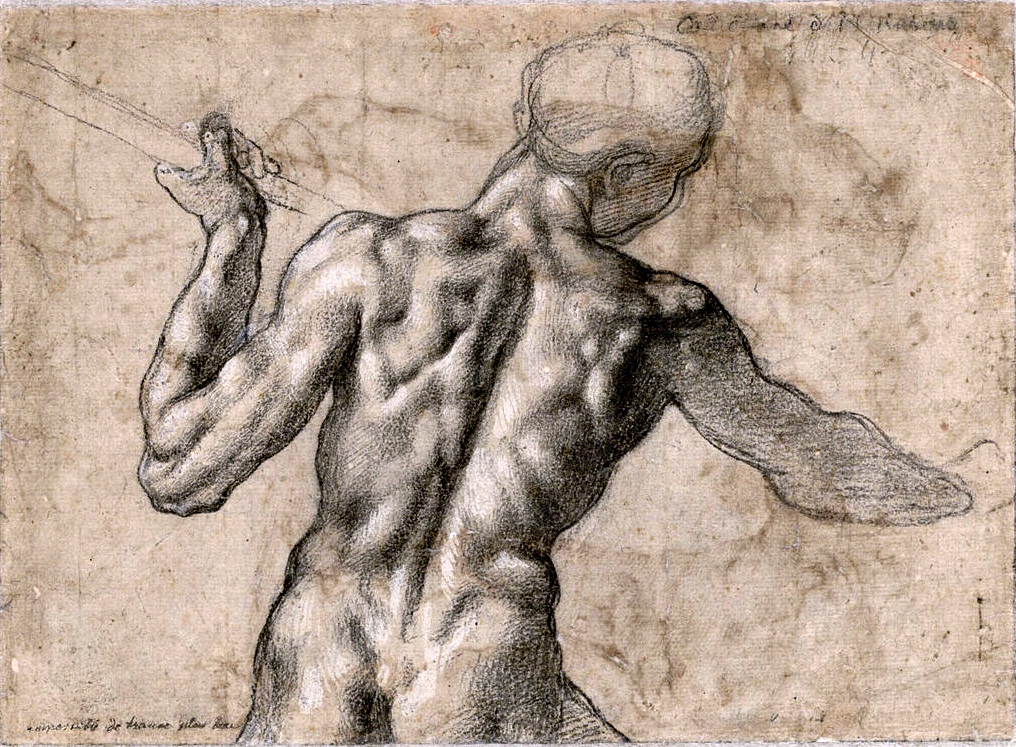

Commissioned by Cardinal Richelieu for his Palais Royal’s Gallery of Illustrious Men the painting of Gaucher de Châtillon was set into one of its bays. The portrait was greatly admired in that generation for the figure’s resolute pose as well as the execution of Vouet’s drawing and painting. Critics assessed that since the pose and head were so artistically beautiful Vouet’s subject was not modeled from life but inspired by Carracci. Seeing the subject turned and from behind was in the Mannerist tradition that Vouet loved and adopted for this historical figure of Gaucher de Châtillon (1250-1328), a constable of France and advisor to Capet kings, Philip IV the Fair (1268-1314), and then to his sons, Louis X the Quarreler (1289-1316), Philip V the Tall (1293-1322) and Charles IV the Bald (1294-1328). The Louvre’s picture has been restored.

Back in France Vouet had a successful career as the painter of large decorations and religious and allegorical paintings. His studio was the largest international workshop and school in Paris. Vouet was a most sought-after and beloved teacher and his art collaborators were numerous (Le Brun, Le Sueur, Mignard, Du Fresnoy, Le Nostre, among others). Per usual practice among professional artists in Europe, those with talent were encouraged to marry into the master’s family so to keep the training, skill and social connections “in house.”

The 1630’s began an age of cultural realignment and reorientation in France that would remain until about the French Revolution. In 1634 the Académie Française was founded under Cardinal Richelieu. In 1637 René Descartes published in French his Discourse on Method (“Je pense, donc je suis” “I think, therefore I am”) ushering in radical subjectivity in philosophical thought. That same year Peter Corneille’s Le Cid was produced, the first great stage play. In 1640 the Imprimerie Royale was founded to publish scholarly books and improve societal erudition. The decade’s innovations continued to transform culture over the next 30 years. By the 1660s French artists, writers and others in France viewed their language, thought, and artistic culture as the world’s most refined and unparalleled in history. Vouet’s return in 1627 was well situated for him to contribute to this prolonged period of interest in artistic matters in France.

In the mid17th century, wealthy French patrons began to collect Italian and Italian-inspired art. This included Louis Phélypeaux de La Vrillière (1599-1681) who collected 240 major paintings for his house in Paris. Critics have observed about Vouet that as he played the role of art functionary by importing and translating Italian art tradition into France, he remained less of a truly profound original artist.

In the 1630s, classical understanding of Carraci from Domenichino (1581-1641) was giving way to a different understanding of history painting from Giovanni Lanfranco (1582-1647). Lanfranco viewed Caracci’s legacy as decoration in search of vitality more than a spatial or formal articulation which extended to include figures in action. Vouet worked rapidly to populate the churches, monasteries and abbeys, royal palaces and private mansions, many newly built, of Paris, with his artwork. Vouet also produced large public commissions, all of which expressed a prevailing Baroque potpourri.

Vouet’s most significant contribution to French painting is his innovations in decorative painting whose influence was felt in France into the mid18th century. Vouet’s influence may be out sized to his intellectual quality and artistic originality but he made a tremendous impression on his contemporaries and was the artist, in a city of intense competition, who was the leading figure of the new Italian art manner for the French public and in many different projects for over 20 years. Vouet’s position as painter is on par with architects Jacques Lemercier (c.1585-1654) and Louis Le Vau (1612-1660) as part of that same generation in France who formed the classicizing French Baroque. They used French art practice since King Francis I (1494-1547) and solid current Roman practice forged into a French synthesis associated with Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII. Vouet’s pupils, Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), Pierre Mignard (1612-1695), Nicolas Mignard (1606-1668). Le Sueur (1617-1655), and François Perrier (1590–1650) carried on the tradition of Vouet’s artwork.

For his decorative work Vouet collaborated with artists in other media such as sculptor Jacques Sarrazin (1592-1660). Vouet painted large-scale decorations for royal patrons such as Anne of Austria (1601-1666), wife and mother of French Kings, at Fontainebleau in 1644 and at the Palais Royal between 1643 and 1647. Vouet did a decorative series at the Arsenal. At Hôtel Séguier (no. 16 rue Séguier) in Paris for the chancellor of France, Pierre Séguier (1588-1572), Vouet painted the chapel, library, and lower gallery. In these projects, Vouet reintroduced forgotten French painting traditions of illusionism practiced by Italian artists at Fontainebleau in the 1530s. Vouet synthesized it with the new Italian style in the 1630s, including imitating the use of gold mosaic and big oval designs derived from Venice. Today these decorations survive only by others’ engravings of them.

Some of Vouet’s decorative schemes survive at the Château de Wideville west of Paris. The castle was originally built in the late 16th century and sold to King Louis XIII’s minister of finances, Claude de Bullion (1569-1640), in 1630. Starting in 1632, the new owner set about building and expanding the castle in the Louis XIII style, with red bricks, white quoins and a pair of chimneys. Bullion involved the best decorators including Vouet for painting as well as Jacques Sarrazin (1591-1660) and Philippe de Buyster (1595-1653) for sculpture. Château de Wideville later became base for Louise de La Vallière (1644-1710), maitresse d’amour of King Louis XIV.

Vouet completed a later decorative panel, Muses Urania and Calliope in or around 1640, with the help of his studio. Likely commissioned as an altarpiece for the private chapel of a wealthy Parisian, the painting depicts porcelain skin women, bejeweled drapery, and putti in a classical architecture setting.

With his patrons Vouet was an amenable creator and he was a facile painter. His wealthy and powerful patrons wanted showy decorative artwork painted in the modern Italian manner without very serious religious or political messages for their often newly-acquired or built residences. The Toilet of Venus is exuberant and intriguing though based on the latest Italian art of the day – the theme is inspired by a treatment of Francesco Albani (1578-1660) while the figure of Venus is derived from Annibale Carracci. Though the figures remain weighty in the mode of Italian Naturalism, Vouet transforms the group into curvaceous polished and floating interlocking forms.

As many of Vouet’s large-scale decorative and other works were virtually systematically destroyed in the Revolution so that the connoisseur must assess Vouet’s artistic merit by way of surviving decorative schemes more than individual canvases or fragments, The Presentation in the Temple is an important extant painting by the hand of Vouet that allows qualitative comparisons to other 17th century French artists such as Laurent de La Hyre (1606-1656), Eustache Le Sueur, Charles Le Brun, and Jean-Baptiste Jouvenet (1644-1717). Commissioned for the Jesuits by Richelieu in 1641 for what is today’s Saint-Paul-Saint Louis in Paris’s Marais it was part of a rich ensemble of artifacts whose overall artistic scheme was dedicated to Christ and the French monarchy. Vouet’s presentation theme evokes the birth of Louis XIV and the painting was flanked by sculptures of Jesuit saints and French political figures.

There remains some similarity to what Vouet had produced in Italy in the mid1620s, particularly in The Appearance of the Virgin to St Bruno in Naples, such as his use of diagonals. Yet 15 years later in France Vouet’s composition is more classical in orientation including a rational not emotional or supernatural treatment of the subject more in the style of Nicolas Poussin who was called back to France from Italy the year before.

To give the illusion of grandeur, Vouet provides a very low position at the bottom of the stairs surrounded by gigantic religious architecture of which he paints a fragmentary synecdoche. For depth, Vouet interposes firmly-modeled foreground figures that partly mask more distant such figures in statuesque draping. Vouet’s cool colors reflect the influence of Philippe de Champaigne and the Baroque turning movement extends into the entablature of the architecture of the temple of Jerusalem, as well as the inclined position of the two angels painted in the upper portion.

By 1762, 20 years after Vouet painted The Presentation, politics changed unpleasantly for the Jesuits as they were suppressed by the Pope and their Paris flagship church’s high altar ensemble was dismantled. The painting was housed in the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture and later transferred to the Louvre during the French Revolution.

In 1651, two years after the death of Vouet, the painting above was inscribed in Latin to state that Vouet had painted the artwork and in the house of “very noble lord” Louis de Hesselin, one of the king’s advisors. The inscription also gives the meaning of the palm branch the Virgin holds – it is a sign of the means of her effectual assistance to the afflicted. Sieur Hesselin was a confident to the artist who was both godfather to Vouet’s eldest son in 1638 and witness to the marriage of Vouet’s daughter 10 years later. Two other known versions of the painting are found in the United States and in England. X-rays revealed that Vouet fully completed the neckline of the virgin before he added the painted golden robe upon it.

Louis XIV owned this painting of Christ being scourged by Roman soldiers at the pillar during his Passion. In the 18th century the painting was attributed to Eustache Le Sueur which still has its defenders today. Attribution to Simon Vouet began in the 20th century among scholars. In the 21st century scholars have proposed Charles le Brun (1619-1690) and the “Workshop of Simon Vouet” which the Louvre has settled upon. Preparatory drawings for the painting exist at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich and at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Besançon. The artwork may have come from a chapel of the Château in Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The painting was restored twice in the 18th century and in the 1960s.

Preparation drawing for a Last Supper picture.

At the same time that Vouet was painting religious subjects for churches in Paris he was painting allegorical and poetical artwork. For these paintings Vouet’s designs are freer, modeling looser and, in the Venetian style, the composition determined more by color and light.

Vouet painted this artwork and two other allegorical paintings for the decoration of the châteauneuf of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In the 17th century the painting was known as “Seated Victory.” The female figure holds a flaming heart in her right hand and palm leaf in her left hand as a Cupid-like figure of love places a laurel wreath on her head. Later, the allegorical figure was called “Faith.” The painting was heavily restored in the mid1960s.

The painting was made for the decoration of the Château Neuf de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In the 18th century the female figure wearing a laurel was described as “Victory” and holding Louis XIV in her arms. In the 19th century the female figure was viewed as an allegory for “Wealth” though other attributes such as the main figure’s foot resting on a cornerstone and strewn open books point to a figure representing “Christian Faith.” The standing cherub who offers her sparkling necklaces and the child on her lap have been interpreted as figures representing earthly and heavenly love, respectively.

Vouet depicts a scene on the standing silver vase of the nymph Daphne being pursued by Apollo, god of the arts. It is a classical mythological story which, despite aid from Cupid, the god of love, relates the vanity of earthly goods and pleasures. The scholarly theory of what is depicted in Vouet’s painting adds up to “Christian Faith” holding onto the figure of heavenly love as she is being tempted by baubles and pleasures of earthly love. The painting was restored in the 1950s and 1980s.

Beyond the thoughtful allegorical presentation, Vouet’s innovative style and reliance on lyrical emotion and sentiment more than ordered arrangement is in evidence as he presents a sensual winged goddess with healthy, chubby children in a fantasia of rich draperies and elegant linear architecture amid a metallic treasure hoard, all of which together enlivens the picture. Its languorous elegance derives from the Italian Baroque. Though a dictatorial teacher, unrivaled ambitious artist, and living in Paris during the grim era of the Thirty Years’ War, in Vouet’s painting for the French nobility there is no sense of unease and any subject’s forthrightness is tempered by superficiality.

A chasm of space between the two angels holding up the shroud and the three women at the tomb before dawn on the third day delineates the heavenly from the earthly although these figures are linked by vibrant colors and a reflective animation of spirals. Detailed drawing is forgone for conventional pose and vague, mannered forms. Vouet seems not to be interested in the Biblical story or its meaning per se but the vivacity of the narrative by way of its stylistic elements. In contrast to Poussin’s statuesque figures or Le Valentin’s introspective art, Vouet introduced Baroque lyricism and fancy into French art.

Saturn who represents Time in Roman mythology has tumbled next to a scythe and hourglass, his attributes. Holding him by the hair the bare breasted figure has been identified as Beauty but also Truth and is likely a portrait of Vouet’s Italian wife. Virginia da Vezzo. She holds a lance over him. To the left is Hope who holds out a hook, her symbol, as a trio of cupids pluck feathers from Time’s wings. The allegorical message may be that Love defies Time.

In another allegorical painting of the same theme, Saturn is Father Time. The old man is overcome by Love (Cupid), Beauty or Truth (a bare breasted figure, perhaps Venus), and Hope (holding an anchor, her traditional symbol). Above these in colorful robes is Fama, the figure of fame, who announces herself blowing her trumpet. Fama embraces Occasio, her hair traditionally blowing forward, holding an emblem of wealth, and signifying the fortunate occasion. In Vouet’s picture which synthesizes classical elements such as statuesque figures in the style of Poussin and swirling masses and vibrant colors of the international Baroque style, Time is the victim of what he usually despoils. The large painting originally hung in the Hôtel de Bretonvilliers in Paris.

In the collection of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans (1725-1785) in the Palais-Royal in Paris before 1785, it entered the collection of Louis Philippe Joseph d’Orléans (1747-1793), known as Philippe Égalité afterwards, and was sold in 1800. In 1961 Friends of the Louvre acquired it in New York City and donated it to the Louvre that same year.

The young woman seated on an elevated throne wearing armor is, according to the influential Iconologia of 1593 by Cesare Ripa (1555-1622), the allegory for Reason. The pair of young women, one offering an olive branch and the other a palm branch, are allegories for Peace and Prosperity. The golden vase is decorated with a bacchanalia. Above the main scene are two cherubs bringing a palm frond and laurel with a twisted column wrapped with a vine that symbolizes Friendship.

Vouet painted this allegory of good government about Anne of Austria as she cooperated with Cardinal Mazarin’s peace policies. The painting was probably commissioned for the decoration of Anne of Austria’s apartment at the Palais-Royal around 1645. It was kept in the collection of the Dukes of Orleans at the Palais-Royal in the 18th century. and moved to London after the death of Philippe Égalité. It was purchased in New York by the Société des Amis du Louvre in 1961. The work was re-oiled with glue by Jacques Joyerot and restored in a pictorial layer by Jeanine Roussel-Nazat between 1979 and 1981.

Simon Vouet died in Paris on June 30, 1649 at 59 years old. His burial details are unknown.

SOURCES:

A Dictionary of Art and Artists, Peter and Linda Murray, Penguin Books; Revised,1998.

French Painting in the Golden Age, Christopher Allen, Thames & Hudson, London, 2003.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Ier_Ph%C3%A9lypeaux_de_La_Vrilli%C3%A8re

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Mansart

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Ier_Ph%C3%A9lypeaux_de_La_Vrilli%C3%A8re

French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century, Philip Conisbee, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 2009.

Baroque, Hermann Bauer, Andreas Prater, Ingo F. Walther, Köln: Taschen, 2006.

The Painting of Simon Vouet, William Crelly, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962.

Art and Architecture in France 1500-1700 (Pelican History of Art), Anthony Blunt, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982.

French Painting From Fouquet to Poussin, Albert Chatâlet and Jacques Thuillier, trans. from French by Stuart Gilbert, Skira, 1963.

https://gw.geneanet.org/garric?n=beranger&oc=0&p=radegonde

17th and 18th Century Art Baroque Painting Sculpture Architecture, Julius S. Held, Donald Posner, H.W. Janson, editor, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. and New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1972.

French Painting in the Seventeenth Century, Alain Mérot, trans. by Caroline Beamish, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995.

Kings & Connoisseurs Collecting Art in Seventeenth-Century Europe, Jonathan Brown, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. and Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Mannerism: The Painting and Style of The Late Renaissance, Jacques Bousquet, trans, by Simon Watson Taylor, Braziller, 1964.

Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio, Annick Lemoine, Keith Christiansen, Patrizia Cavazzini, Jean Pierre Cuzin, Gianni Pappi, Metropolitan Museum of Art; 2016.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/194104613/simon-vouet

http://www.museereattu.arles.fr/reattu-collectionneur.html

![Tu Style Magazine [Italy] (9 May 2016)](https://jwalsh2013.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/tu-style-magazine-italy-9-may-2016.jpg)