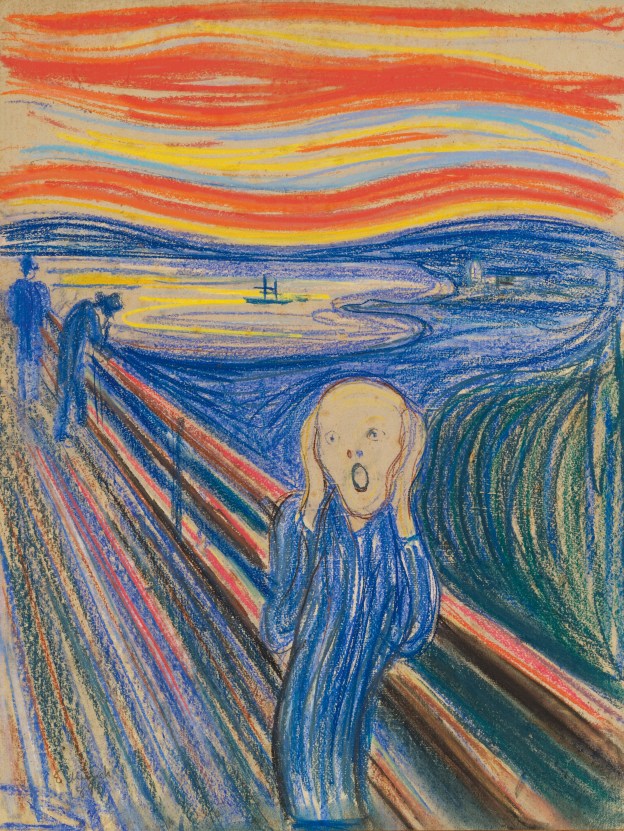

FEATURE image: Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1895, pastel on cardboard, private collection.

By John P. Walsh

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, oil on canvas, 1886.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was a Symbolist and Expressionist artist from Norway.

In the 1890s, anti-naturalism mainly took the form of Symbolism – that is, the fascination with many types of literature and the inclination to draw upon these sources for inspiration in dreams and visions. This movement informed the art of Edvard Munch throughout that decade and into the twentieth century. Inspiration from literature, however, was not illustration. By the 1890s the younger generation of modern artists saw that by giving the artist an example of constructing an irrational logic, the artist’s dream, or more specific to Munch, psychology, had been freed not only from the restrictions of nature in terms of form, line, color and subject but also its potentially literary or ideological sources. It manifests as a style of drawing that the imagination has liberated from the concern of natural details in order that it might freely serve only as the representation of conceived things.

For Edvard Munch, this resulted in the creation of several fantastic scenarios which are designed and constructed as the artist deems them necessary to be. The distinction between Impressionism and Symbolism is the difference emanating from the tradition of naturalism and the expression of ideas by means of its symbol that is searching beyond naturalism.

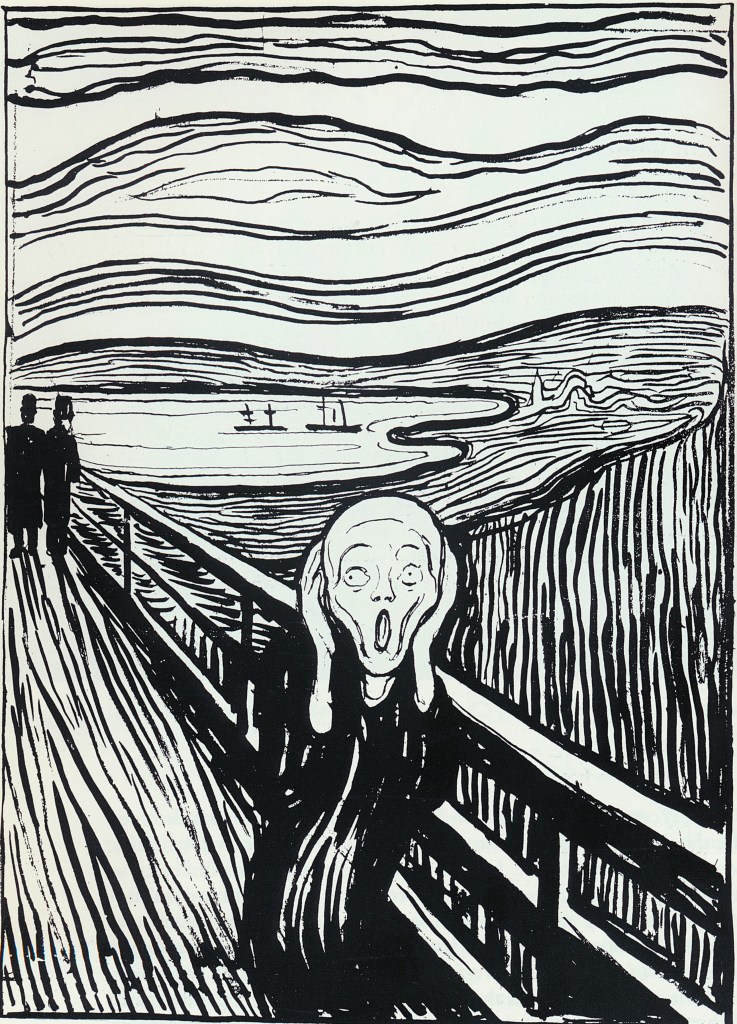

Edvard Munch, The Scream, crayon, 1893.

Edvard Munch is a precursor and practitioner of Expressionism. Although the major portion of Munch’s artwork lies outside this classification, his expressionist paintings are some of his best-known works.

The Scream is Munch’s most famous work, and is widely interpreted as representing the universal anxiety of modern man. It is one of modern art’s most iconic paintings along with Whistler’s mother (Arrangement in Grey and Black, Number One, D’Orsay), Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (Louvre), and Grant Wood’s American Gothic (Chicago).

Expressionism was a movement that was a combination of Symbolism, ideals of the human spirit, often confined in solitude, and poetical lyricism laced with emotion.1

1870’s, 1880’s KRISTIANIA (OSLO): MUNCH’S FIRST ARTWORK AND “THE SEEDS OF MADNESS”

In an artistic career that spanned from the early 1880s until his death in 1944 at 80 years old, Edvard Munch experimented within painting, graphic art, drawing, sculpture, photography and film.

Growing up in Kristiania (today’s Oslo) Munch decided at 17 years old that he was going to be a painter. Munch’s family encouraged his artistic pursuits so that in 1880 Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania where he expanded his drawing repertoire to include live models and en pleine aire (out of doors).

Often ill as a child, Munch believed that in his experiences growing up, “…I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born.”

In his career, Munch painted mania in several pictures, including Melancholy (1901). It depicted his younger sister Laura who suffered from schizophrenia, and was hospitalized regularly for what was diagnosed as “hysteria” and “melancholia.”2

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, Laura, 1901.

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, 1882, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Interior Pilestredet, oil on canvas, 1881, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Still Life with Jar, Apple, Walnut and Coconut, 1881, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, From Saxegårdsgate, c. 1882, oil on canvas, Lillehammer Art Museum.

Edvard Munch, Laura, both 1882, oil on paper (top) and oil on cardboard (below), Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Andreas Studying Anatomy, 1883, Oil on Cardboard, Munch Museum, Oslo.

SOUL PAINTING: MUNCH’S FIRST ARTISTIC BREAKTHROUGH

Between 1884 and 1889 young Munch made a range of drawing and paintings that was extensive and meaningful. His portfolio included landscapes, domestic environments, portraits, self-portrait, still life, and fictional motifs. Munch’s drawings included industrial sites along the Akerselva River, and promenading denizens and local farmers at work.

In Munch’s early work there is a hint of his wrestling with eros and the nature of woman that became a lifelong obsession.

In Kristiania Munch began to live a bohemian life under the influence of anti-establishment writer Hans Jaeger (1854-1910). Jaeger urged Munch to paint his own emotional and psychological state called “soul painting.”

Munch’s first “soul painting” was The Sick Child (1886). The artist produced five versions over decades. Munch’s freedom of treatment and color – also found in the painting Tête-à-Tête in 1885 – is largely owed to Impressionism. In 1886, Munch participated in the Artists’ Autumn Exhibition in Kristiania and exhibited The Sick Child. It met with very negative reaction. The motif of the sick was popular but Munch’s hasty Impressionistic treatment was seen as insensitive. It was the first breakthrough for Munch’s art.

Edvard Munch, Tête-à-tête, oil on canvas, 1885, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child (original version), 1885-86, National Gallery, Oslo. Other versions are in the Konstmuseet Gothenberg (1896), Tate London (1907), Thiel Gallery (1907) and Munch Museum (1925).

Munch later painted Hans Jaeger’s portrait in Oslo in 1889 after Jaeger lost his job and had to flee Norway one step ahead of the law. This was after Jaeger published a novel about local Bohemian life that the authorities considered inflammatory. Young Munch began to explore in his art personal situations, emotions, and states of mind. He wrote in his “soul” diary: ” I attempt In my art to explain life and its meaning to myself.”3

Edvard Munch, Hans Jæger, 1889, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Night on the Beach, 1889, Bergen Art Museum. Known also as Inger on the Beach, it was painted in the summer of 1889 at Åsgårdstrand. The sitter is Munch’s youngest sister Inger. The artwork created a storm of confusion and controversy. Its simplified forms, thick outlines, contrasting colors and shades, and subtle emotional content signaled the direction of Munch’s developing style.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait, c. 1888, Munch Museum, Oslo.

PARIS AND ÅSGÅRDSTRAND IN 1885: MUNCH ENCOUNTERS OLD MASTERS, MODERNIST ÉDOUARD MANET—AND HAS HIS FIRST LOVE AFFAIR

With friends, Munch rented a studio in Kristiania. His mentor, established artist Christian Krohg (1852-1925), encouraged Munch to conform to his own artistic vision.

In 1885, 22-year-old Munch traveled to Paris for the first time to explore the world’s art capital. During his three-week stay in Paris Munch visited the Louvre and the Salon and was particularly impressed by French Modernist painter, Édouard Manet (1832-1883). Munch began to incorporate those ideas and techniques of French Modernism into his artistic vision. In the same year Munch produced his full-length Portrait of the Painter Jensen -Hjell to the derision of critics in Kristiania. The penchant for Manet’s artwork continued for Munch into the new century with a full-length portrait called The Frenchman (Monsieur Archimard) in 1901.

In summer of 1885 Munch had his first love affair which affected him deeply. It occurred in the coastal resort town of Åsgårdstrand when Munch met Milly Thaulow (1860-1937), a fashion model and singer.

Milly had been married since 1881 when she met Munch and they had a passionate affair. The short, secret relationship filled Munch with mixed feelings of love and shame. Its inevitable ending produced melancholy that affected Munch’s artmaking.

Milly Thaulow remained active in the arts, translating Maurice Maeterlinck’s French play, Pelléas et Mélisande, into Norwegian in 1906. She went on to divorce her husband in 1891 and remarry that same year. Her second marriage ended in divorce. In the end, Munch justified his experience with Milly as part of radical bohemian artist culture which Hans Jaeger preached where love is free and self-expression is paramount.

Edvard Munch, Portrait of the Painter Jensen -Hjell, 1885, National Gallery, Oslo.

PARIS IN 1889-91: MUNCH’S MODERNIST VISION AND TECHNIQUE

In 1889 Munch rented exhibition space in Kristiania to display 110 of his artworks. His entrepreneurship resulted in receiving state grant funds that led to a second, yet back and forth, stay to Paris whose time amounted overall to about two years.

In Paris, Munch took drawing lessons, explored art galleries, and networked with expatriate artists, especially at the venerable 17th-century Café de la Régence near the Palais-Royal.

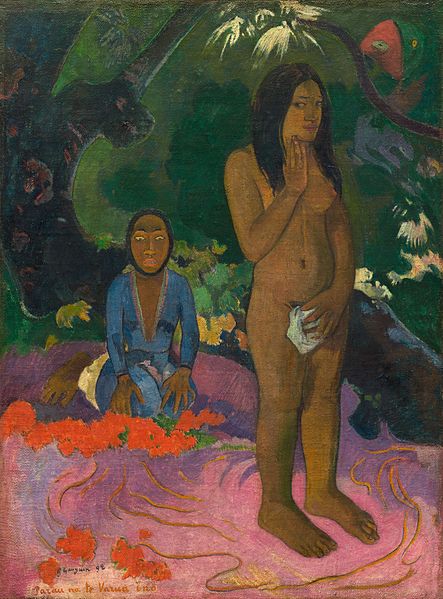

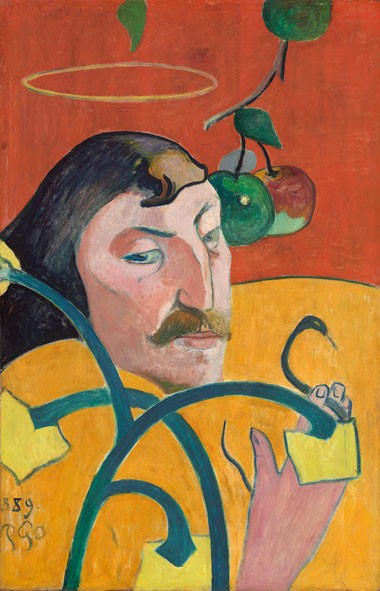

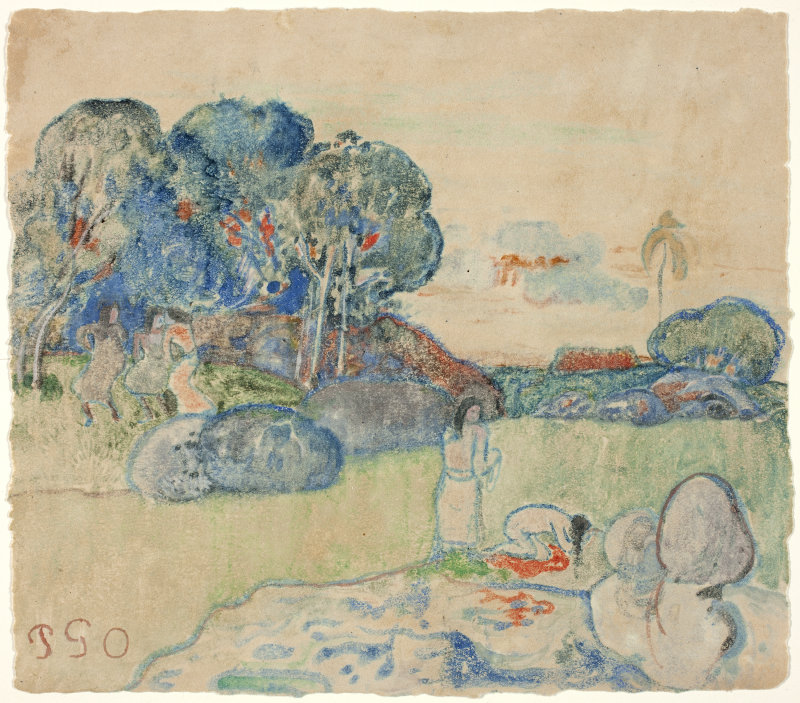

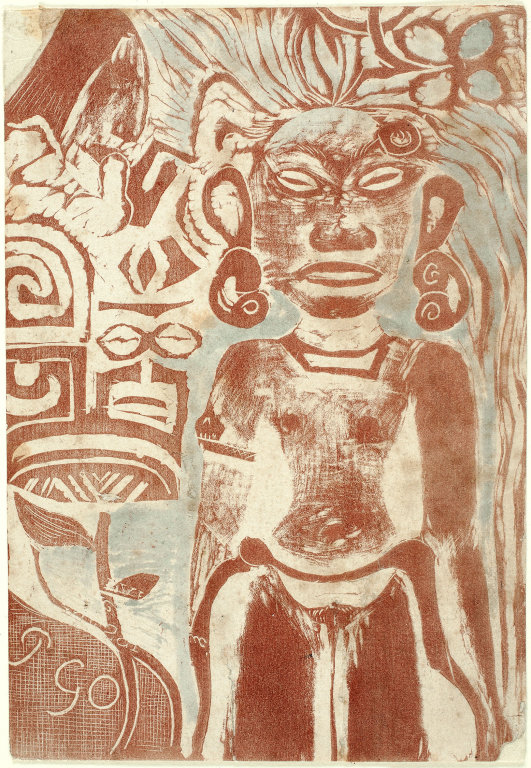

In his study, Munch became inspired by the rhythmical and decorative art of Paul Gauguin (1847-1903), several of the Nabis, Japonisme, and the Symbolist drawing of Odilon Redon (1840-1916).

Though Munch rejected Realism in art, he embraced Impressionism, particularly the technique of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Thomas Couture (1815-1879). Munch was particularly impressed by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and their unnatural use of color to express sensory perception and emotion. In this milieu Munch painted Rue Lafayette (1891).

The 26-year-old Munch had just arrived into Paris when his father died, an event which devastated the artist. Running low on money, Munch left the city and, with Danish poet Goldstein, rented a small apartment in the suburb of St. Cloud.

Munch’s experiences of relative poverty and the death of a loved one offered new insights and impetus for his art in terms of seeking to understand and express the memory of his human existence.

He painted Night In St. Cloud (1890) and Evening on the Karl Johan (1889) in this time period. Munch also conceived the idea of The Frieze of Life, a series of paintings exploring human existence from a range of pathos, terror, desire, dread, nightmare, and anxiety, to other fascinations, so to include The Dance of Life, The Scream, The Vampire, Madonna, and Death and the Maiden.

In 1891 Munch had exhibitions in Kristiania, Berlin, and Munich. He returned to Paris several times in the next decade for short term visits as in 1899 which included a trip to Italy.4

Edvard Munch, Night In St. Cloud, 1890, oil on canvas, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening on the Karl Johan, 1889, oil, Bergen Art Museum.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the Window, 1891, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening Melancholy, 1891, oil, crayon, pencil on canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Rue Lafayette, 1891, oil on canvas, National Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Rue de Rivoli, 1891, oil on canvas, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Edvard Munch, Inger in a White Blouse, 1891, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Pleine-aire, 1891, oil on canvas, 60 x 120 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

BERLIN 1892-1895: MUNCH’S ARTISTIC POWER REACH MATURITY

In 1892, Munch’s pictures were again exhibited at the Autumn Exhibition in Oslo (it was his final time)–and led to the 29-year-old artist being invited to exhibit at the Verein der Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists) in Germany in November 1892 for a one-man exhibition.

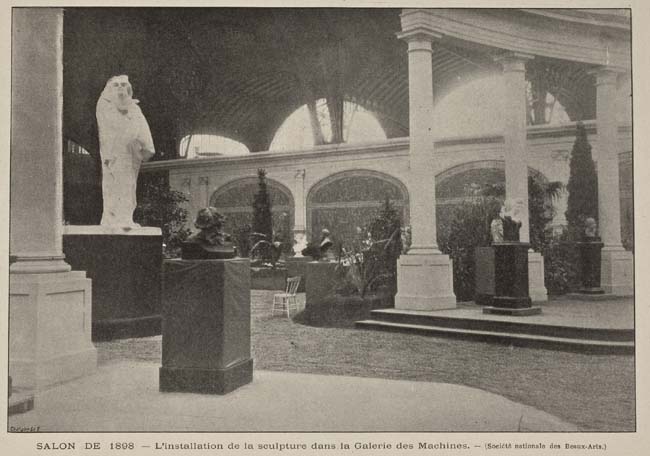

Munch’s exhibition of Melancholy (1891) in Oslo was called Norway’s “first Symbolist painting.” His exhibition of 55 pictures in Berlin proved another breakthrough for Munch’s reputation in Europe: it made him infamous. The critical reaction to his artwork was divided. Critics described Munch’s art as “repugnant, ugly and mean.” As it shocked the Berlin public, German artists Max Liebermann (1847-1935) and Ludwig von Hofmann (1861-1945) setting up a dissident “Group of XI” that led to the establishment of the Berlin Secession later on May 2, 1898.

The government of Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859-1941) set the mood for the public reaction in that art which “presumes to overstep the limits and rules” which Wilhelm had set, “is no longer art.” In the eyes of German society, Munch’s artwork “misused the word ‘freedom’ and (with) a total loss of restraint and excess of self-esteem.”

Later, by around 1910, that same Emperor in his constant pursuit of cultural influence, mostly supported the Berlin Secession. Yet the Secession’s public and financial success which Wilhelm II eventually helped to build, came at the price of a benevolent autocrat’s constant interference, particularly in the modern art group’s jury process.

Munch stayed in Berlin until 1895. In the Berlin exhibitions of 1893 and 1895 Munch presented a sequence of pictures he called Man’s Life, From the Modern Life of the Soul and, simply, Love. These all contained artwork that contributed to The Frieze which Munch intended to be a symbolic expression of reality and not a mere symbol of or for reality.

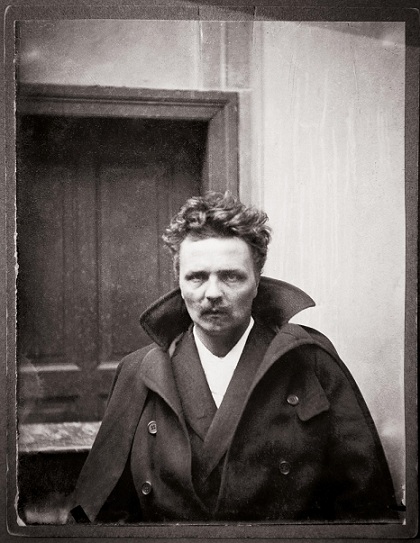

Munch’s bohemian circle in Berlin included editors of the magazine Pan, the German arts publication analogous to France’s La Revue Blanche. It also included Swedish avant-garde writer, August Strindberg (1849-1912) who would soon provide Munch with influential introductions to the Berlin and Paris art worlds. In 1890 Strindberg broke with naturalism and was in his own artistic and personal crisis as he sought new art forms within an emerging Symbolism. Munch met German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe (1867-1935) and socialized with Polish decadent naturalist and Symbolist novelist, dramatist, and poet Stanisław Przybyszewski (1868-1927) along with Przybyszewski’s paramour and later short-term wife, Dagny Juel (1867-1901). Munch painted both of these friends’ portraits.

Munch’s Berlin friends understood what Munch was doing with symbolism though the German critics did not. Przybyszewski wrote: “The old kind of art and psychology was an art and psychology of the conscious personality, whereas the new art is the art of the individual. Men dream and their dreams open up vistas of a new world to them.”

In addition to exhibiting in Berlin in both 1893 and 1894, Munch exhibited in Copenhagen, Dresden and Munich in 1893 and in Stockholm in 1894.

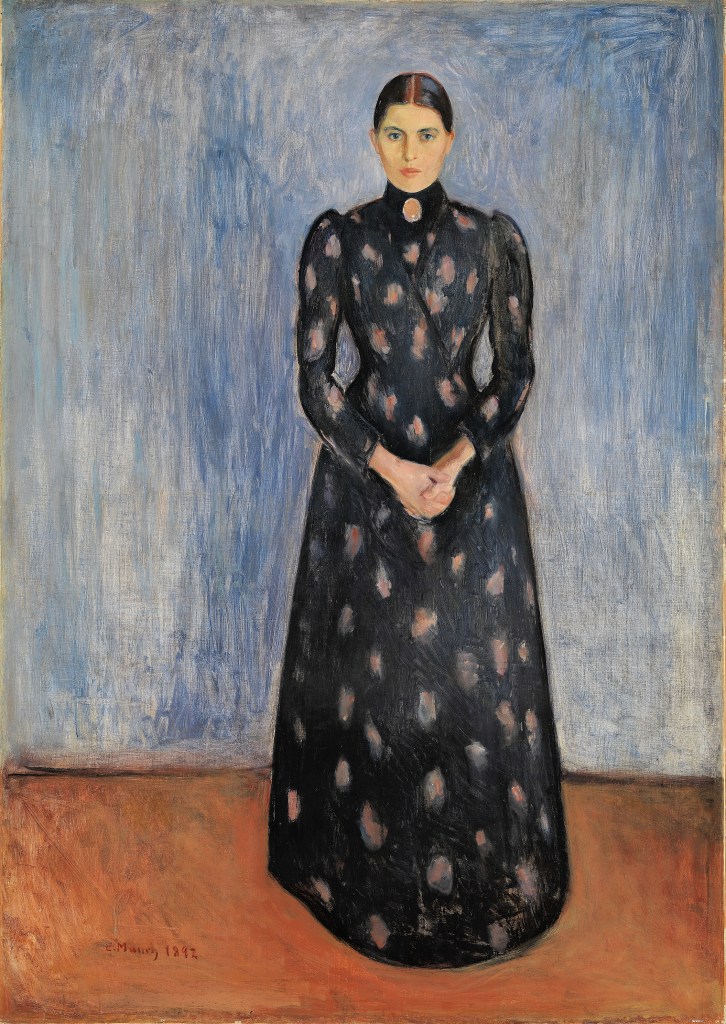

Working on the Frieze of Life, Munch created painting with turbulent, ambiguous and morose themes with titles such as Despair (1892), The Girl and Death (1893), Stormy Night (1893), The Voice (1893), Anxiety (1894), The Three Stages of Woman (1894), Ashes (1894), Death Struggle (1895), and Jealousy (1895). Aspects of Symbolism extended to romantic aspects of nature in paintings such as Coastal Mysticism (1892), Evening (Melancholy) (1893), Moonlight (1893), Starlit Night (1893), Sunrise at Åsgårdstrand (1893) and The Evening Star (1894). He painted many portraits in this period, in addition to those in his Berlin Bohemian circle, including Sister Inger (1892). Other iconic, overtly anecdotal Munch paintings were created such as Self Portrait in Hell (1895), Self Portrait under a female mask (1892), and Self portrait with Burning Cigarette (1895).

Other paintings, including casino scenes, showed Munch’s simplification of form and detail. The artist favored shallow pictorial space and a minimal backdrop for his foreground figures. Poses, forms, colors, lines and subjects were carefully constructed images that expressed psychological and emotional states, and often appear monumental as if they were playing a role on the stage of life.5

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, 1893, oil, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy (The Yellow Boat), 1891, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the window, 1892, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1892, oil, Private Collection.

Edvard Munch, The Girl by the Window, 1893, oil, Art Institute of Chicago.

Edvard Munch, Separation, 1893-94, Gouache, watercolor and crayon on paper, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Parting, 1894, oil on canvas, 67 x 128 cm, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Three Stages of Women (Sphinx), c. 1894, Bergan. Munch painted woman as dreaming, hungry for life, and as a nun.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894–1895, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 110 cm, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Anxiety, 1894, Munch Museum. Art critics see the painting as closely related to The Scream (1893). The faces show despair and the colors impress a depressed state showing emotions of heartbreak and sorrow.

Edvard Munch, Despair, 1893, oil on canvas, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, The Storm, oil on canvas, 1893, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

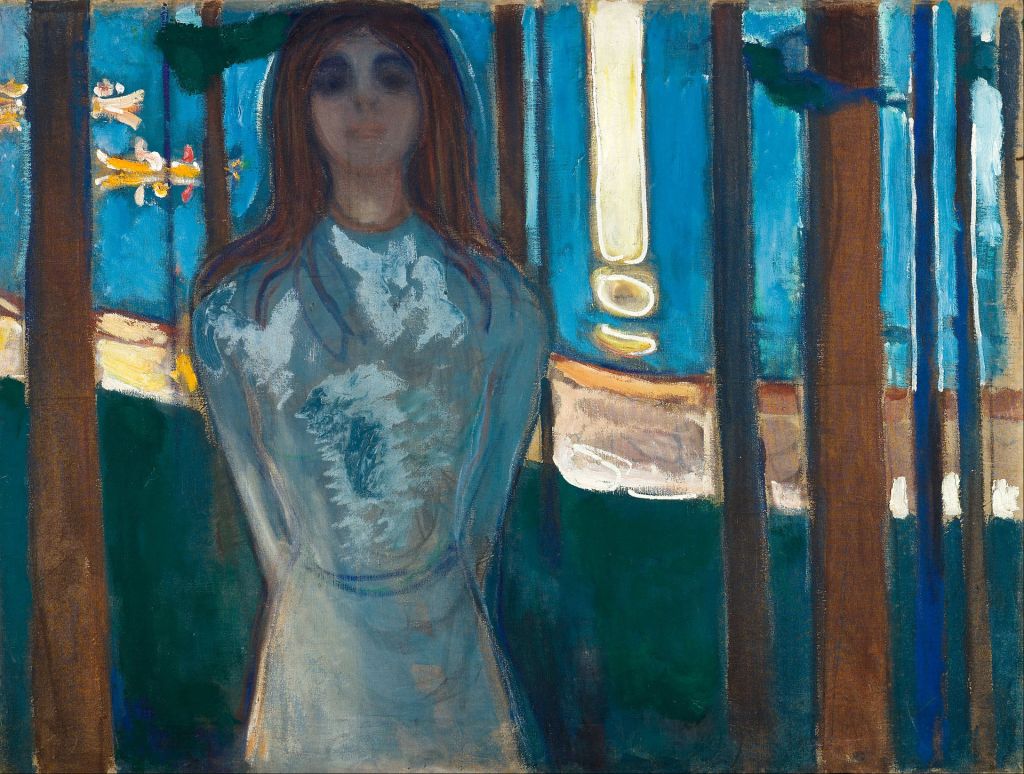

Edvard Munch, Summer Night’s Dream The Voice, 1893, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

Edvard Munch, Coastal Mysticism, 1892.

Edvard Munch, The Hands, 1893, oil on canvas, 91 x 77 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, At the Roulette Table in Monte Carlo, 1892, oil, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait Under the Mask of the Woman, 1893, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait with Burning Cigarette, 1895, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait in Hell, c. 1895, oil on canvas, 82 x 60 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Stanislaw Przybyszewski,1895, pastel, 62x55cm, Munch Museum.

PARIS IN 1895 TO 1897: MUNCH ADOPTS “IDEA” PAINTING. THE SCREAM

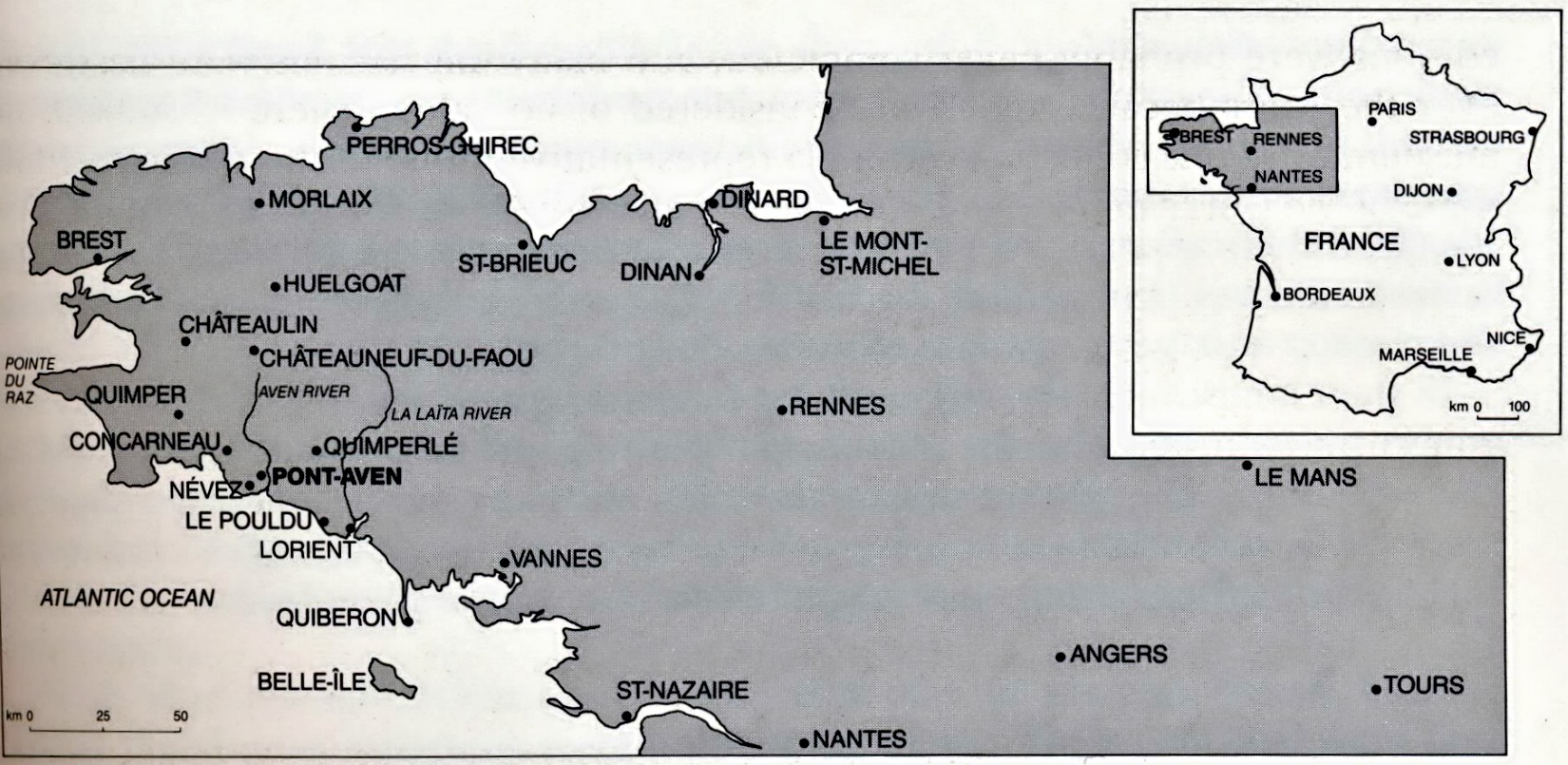

Until 1870, young artists from Norway went to Dűsseldorf to study and pursue an art career though sometimes to Berlin, Paris, Munich and Karlesruhe. By 1880, Paris was the center of the art world and Munch returned to Paris in 1895, 1896, and 1897 for extended visits (he also visited Nice in 1897).

Thadée Nathanson’s La Revue Blanche published Munch’s lithograph The Scream in December 1895. The Scream exists in four versions: two pastels (1893 and 1895) and two paintings (1893 and 1910). There are several lithographs of The Scream from 1895 and later.

With The Scream, Munch met his stated goal in his diary of his art expressing “the study of the soul, that is to say the study of my own self.” Philippe Jullian argues that it had been the combination of influences of Strindberg, Redon, and Gauguin that explained Munch’s conversion from Naturalism and Impressionism to “Idea” painting expressed in Symbolism. Munch was the first to express the individual’s anguish in modern society and facing death. He was an inventor of the ectoplasm line (“ectoplasm” is a spiritualism term first used in 1894). Munch’s figures, including The Scream, emerges from pastel, oil, or ink like an apparition, yet to be identified with the “souls” of ordinary persons.

Anxiety, jealousy, loneliness; Munch illustrates people who pictorially express Symbolism’s darkest visions and themes.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1895. Ink.

In Paris Munch exhibitions were organized at the Salon des Indépendents and Siegfried Bing’s Salon de L‘Art Nouveau. Young avant-garde art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) included Munch in his first Album des Peintres Graveurs. Munch was commissioned by the Cent Bibliophiles to illustrate Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil. Like young Nabis Édouard Vuillard (1868-1940) and Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947), Munch designed programs for Symbolist theatre (Ibsen’s Peer Gynt at the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre). He did portraits of Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842-1898) and August Strindberg. Munch created some of his most iconic motifs, including The Scream (pastel version), Vampire (a woman seductive and destructive), Puberty (an anxious girl seated naked on a bed), and Madonna (a synthesis of the mystical and erotic).

MUNCH MASTERS MODERN EXPERIMENTAL PRINTMAKING

In Berlin in 1894 Munch had produced his first dry point etchings. In Paris in 1896, following the explosion of color printing in the 1890’s, Munch produced his first color lithographs and woodcuts (Vampire was his first woodcut). Influenced by Gauguin and Max Klinger (1857-1920), printmaking allowed Munch to be highly experimental in the creation of an image. Particular to Munch as an artist, the subject of the artwork determined which of the various styles to be deployed. At his death Munch retained over 15,000 prints in his Oslo studios. During his lifetime, inspired importantly by his work in mid-1890’s Paris, Munch became a master of all graphic techniques, such as color, volume, and line. Munch’s production of an immense portfolio of graphic art sought to create images which are subordinated to the experiences of the self’s impulses and drives.

Munch’s attempts to market his new artwork in Paris as he did in Berlin to acceptance and fame resulted in relative failure in the world’s art capital. His parting milestone in Paris in this period was in the 1897 Salon des Artistes Indépendants where Munch displayed in the main hall his ever-augmenting Frieze of Life. The cycle was characterized by continuous reworkings as new paintings; versions that replaced paintings which had sold; and, new compositions added to the series.

In terms of public acclaim, the effort appeared for naught. French resistance to Munch’s “repugnant, ugly and mean” art endured. French critics decried Munch’s art as “violent and brutal” and, when they weren’t chastising him, they ignored him—and this attitude lasted deep into the 20th century. However, another exhibition in Munch’s native Oslo of 85 paintings was well received.6

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1895, Dry-point and aquatint, 34.8 x 28 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, woodcut, n.d., 44.7 x 44.7. cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Jealousy, 1896, Lithograph, 46.5 x 56.5 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death and the Maiden, 1894, Dry-point, 30.2 x 22 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy (Evening),1896, woodcut, 37.6 x 45.5. cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Attraction, 1896, Lithograph, 47.2 x 35.5 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1896, Lithograph, 42.1 x 56.5 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening, Melancholy I, woodcut, 1896.

Edvard Munch, Stéphane Mallarmé, 1896, lithograph.

Edvard Munch, August Strindberg, 1896, lithograph.

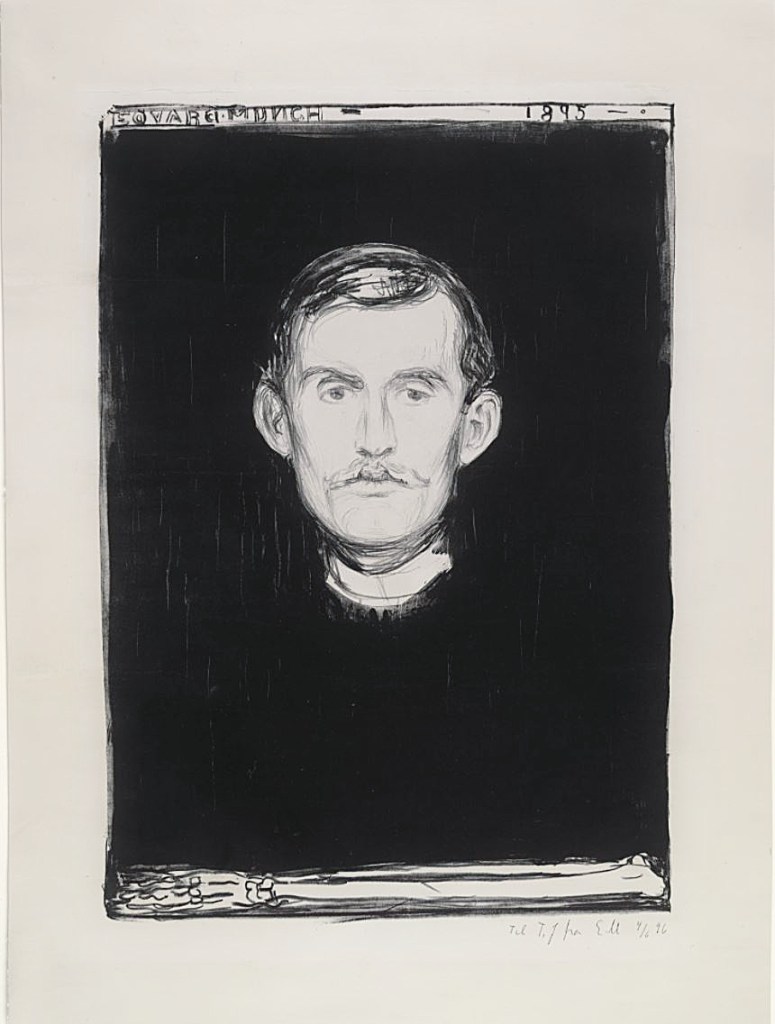

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, 1895, Lithograph, 45.5×31.7 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Munch was 31 years when he produced this self-portrait. It is a memento mori – a reminder of death. The bones at the bottom of the image are paired with the artist’s name and the date of the lithograph’s creation at the top. The floating head in a sea of darkness was a familiar motif in art in the 1890’s expressing in part the cosmic and ontological realities of humanity.

Edvard Munch, Lady From the Sea (detail), 1896, oil on canvas. 100 cm × 320 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Voice Summer Night, 1896, 90 cm × 119 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo

Edvard Munch, Paris Boulevard, 1896, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 130 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

MUNCH’S AMBIVALENCE IN LOVE AND OBSESSION WITH DEATH

In 1898 Munch met Tulla (Mathilde Larsen) and they became lovers. Munch continued a productive period of art-making as he continually refused to marry Tulla. Munch portrayed many artworks displaying his view of life and death and the destructive force of love where both man and woman suffer– Madonna (1893), Salome, The Maiden and the Heart (1896), Under the Yoke (1896), Cruelty, The Woman and the Urn (1896), and, later, his Alpha and Omega lithograph series (1909). Munch remained fascinated by women as expressed in The Kiss (1892), The Three Stages of Women (1894), and The Dance of Life (1900).

One explanation of the ambivalent relationship of Munch the artist and Woman as artistic subject may be understood through the Symbolist art aesthetic. Symbolism connoted the idea of a desirable union of the human being with a philosophic ideal. In its view, Woman, though called real is a false appearance, and thereby not ideal. Further, Woman acts mainly as a temptress, the then-popular notion of a femme fatale, as she reveals man’s animal nature which obscures and prevents the desirable union to the ideal. Woman must be avoided and, if engaged by man, done so with peril.

Munch was an idealist before he became a Symbolist, and, as Christian Krohg ominously wrote about him in 1892: “dares to subordinate Nature, his model, to the mood.“

In 1899 Munch exhibited at the Venice Biennale and in Dresden. The Berlin Secession held its first exhibition in 1899 on its own premises but did not invite Edvard Munch. Though the Berlin group invited no foreigners that year, Munch’s art continued to be viewed by status quo cognoscenti as “undesirable.” Yet, at the same time, Munch’s art was beginning to influence young Expressionist artists in Germany. In artworks such as The Voice and Summer’s Night, Munch appealed to these younger avant-garde artists for his illustrating the upsurge and resonance of raw emotion.

Edvard Munch, The Inheritance, 1897-99, oil on canvas, 141 x 121 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Two people, 1899, oil on canvas, 175 x 143 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo

Edvard Munch, Amor and Psyche, 1907, oil on canvas, 118 x 99 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Marat’s death, 1907, oil on canvas, 151 x148 cm, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, The Murderess, 1906, Munch museum.

Edvard Munch, Death of Marat I, 1907, 150 x 199 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the Window, 1897, oil on canvas, 99 x 80.5 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death and the Maiden, 1893, oil on canvas, 128 x 86 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Stanislaw Przybyszewski (The Vampire), Oil and/or tempera on unprimed cardboard, 1893.

MUNCH IN THE NEW CENTURY; THE FRIEZE OF LIFE

Little is known about Munch’s personal relationships with individual women that would greatly enlighten the artist’s overall character and how these relationships’ impacted his artwork in his adult years. Fantastic stories are told. How, in his room at Åsgårdstrand with an unknown woman (likely Tulla), did a gunshot go off in Fall 1902 from a revolver that injured Munch’s hand? Munch successfully chased Tulla out of his life, though after she married another man, the artist felt betrayed by Love and brooded over it. Even as Munch had numerous short-lived affairs with beautiful women who wanted to marry him, he fled them all and verbally expressed no known regrets. Throughout his life, Edvard Munch never married.

Munch started the year 1900 in Gudbrandsdalen and moved on to Berlin. In 1901 he painted in Nordstrand and in 1902 returned to Berlin. Along with artwork of Édouard Manet, Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), and Claude Monet, Munch exhibited at the Berlin Secession in 1902. He had continually worked at the Frieze of Life, the group of images representing human existence, a subject that fascinated the artist. He exhibited 22 paintings from the completed Frieze at that year’s Berlin Secession. Though the Berlin critics began to appreciate Munch’s art, the public continued to view him as warped and weird. In 1902 he met ophthalmologist Dr. Max Linde (1862-1940), an art collector and author of a Munch study while Hamburg judge and art collector Gustav Schiefler (1857-1935) started a catalogue of Munch’s voluminous graphic art that year.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait Against a Green Background and Caricature Portrait of Tulla Larsen, 1905.

Edvard Munch, Ashes, 1893,

Edvard Munch, The Dance of Life, 1899-1900.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1894, Munch Museum, Oslo.

In 1903 Munch visited Dr. Max Linde in Lübeck and painted a frieze for his house though Dr. Linde ended up rejecting Munch’s work. Munch exhibited in Berlin at Paul Cassirer modern art gallery.

EVA MUDOCCI’S PREGNANCY AND MUNCH’S NERVOUS BREAKDOWN

In 1903 Munch met British violinist Eva Mudocci (1872-1953) in Paris where Munch had an exhibition. Fully aware of his commitment only to art, Eva Mudocci reportedly became Munch’s mistress and Munch soon immortalized her in The Woman with the Brooch.

In this period, Munch received several commissions for portraits and prints. In 1904 the German rights to his graphic art and paintings was sold to two prominent galleries. Munch exhibited in Vienna and Paris and became a member of the Berlin Secession. In 1905 Munch exhibited 75 paintings in Prague at the Manés Gallery and in 1906 was invited to exhibit with the Fauves in Paris. In Berlin, Munch painted stage sets for Henrik Ibsen plays (Ghosts and Hedda Gabler) at the Max Reinhardt Theatre. A frieze that was commissioned for the Reinhardt Theatre was sold by its director before the frieze was unveiled to the public.

In 1907 Munch summered in Warnemünde as he turned his attention to human figures and situations. He exhibited with Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne at Cassirer Gallery, the purchaser of the German rights to Munch’s graphic art. In November 1907 Eva Mudocci went on a concert tour in Norway for three weeks where She and Munch spent time together in Åsgårdstrand and Oslo. In early 1908 Eva Mudocci was pregnant and gave birth to twins in Denmark at the end of the year. Friends insisted that Munch must have been the father but Mudocci never said who the father was.

Almost simultaneous with Mudocci’s pregnancy, 45-year-old Edvard Munch had a nervous breakdown. In December 1908 he checked himself into a clinic in Copenhagen for several month’s treatment for alcoholism and exhaustion. Munch later wrote: “My condition was verging on madness—it was touch and go.”

In 1909, Mudocci and Munch parted ways though they stayed in touch for the next 18 years, until 1927. At the clinic, Munch painted portraits of his doctor (Dr. Daniel Jacobsen, 1909) and a nurse as well as close friends and a self-portrait using short, thick, and forceful brushstrokes—it was a watershed moment in Munch’s life and art.7

Edvard Munch, Salome, 1903, lithograph.

Edvard Munch, Fertility, 1898, woodcut, 42 x 51.7 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Women on the Beach, 1898, woodcut, 45.5 x 50.8 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Red and White, 1899–1900, 93 cm × 129 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm.

Edvard Munch, Red Virginia Creeper, 1900, oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm.

Edvard Munch, Young People on the Beach, 1902, oil on canvas, 90 x 174 cm.

Edvard Munch, On the beach, 1905, oil on canvas, 81x 121 cm.

Edvard Munch, Bathing Boys, c. 1904, oil on canvas, 194 x 294 cm.

Edvard Munch, Shore with Red House, 1904, oil on canvas, 69 × 109 cm, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Train Smoke,1900, 84 cm × 109 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Nude by the bed, c. 1907, oil on canvas, 120×121 cm

Edvard Munch, Nude by the bed, c.1907, oil on canvas 120×121 cm

Edvard Munch, Four Girls Åsgårdstrand, 1905, oil on canvas, 87x111cm

Edvard Munch, Avenue in the snow, 1906, oil on canvas, 80 x100 cm,

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with Brushes, 1904, 197×91 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine, 1906, 110 cm × 120, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Deathbed, 1900, oil on canvas, 100 x 110 cm.

Edvard Munch, Village Street, 1905, oil on canvas, 100×100 cm.

Edvard Munch, Prayer, 1902, woodcut, 45.8 x32.5 cm.

Edvard Munch, Dr. Daniel Jacobson, 1909, oil on canvas, 204 x 112 cm.

Edvard Munch, Nurse, 1909, dry point, 20.5×15.2 cm.

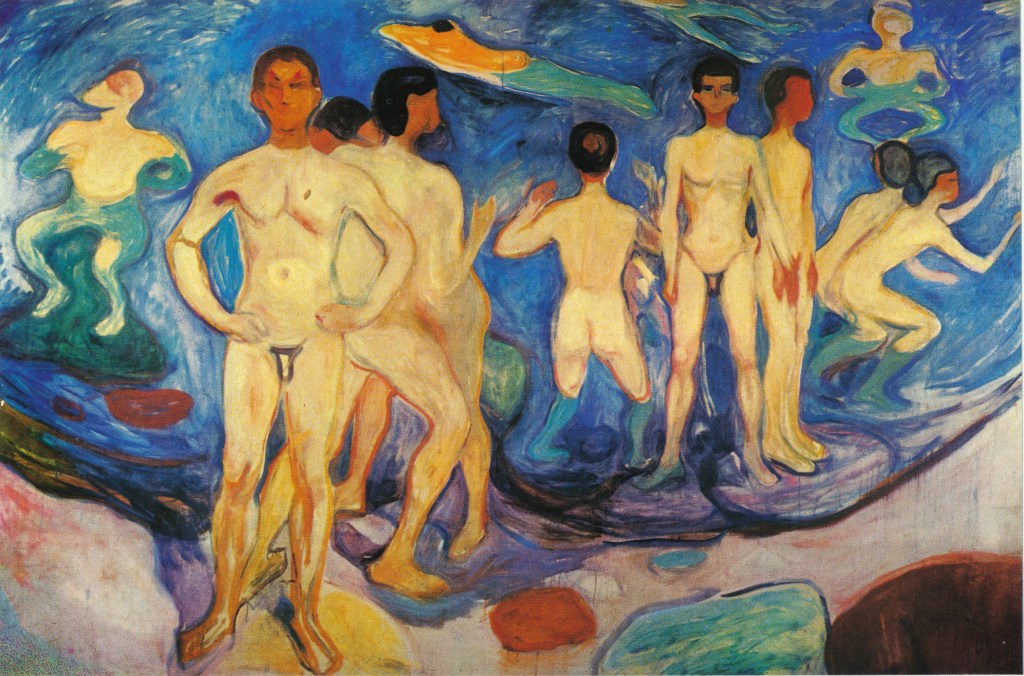

NORWAY 1909: MUNCH COMES HOME

Following his recuperation at the clinic, Munch was sober for the first time in years. In 1907 and 1908 he created Bathing Men, a scene of cleansing by immersion reminiscent of Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). Suddenly the totality of Munch’s art of the 1890’s and early 1900’s, where he explored his dark and tormented feelings, thoughts, and experiences, became passé for the artist. With the same vigorous brushwork and unnatural, expressionistic colors, Munch turned to painting everyday subjects.

Renting a house in Kragerø, a fishing village in Norway, Munch permanently settled in his homeland. In 1912 he exhibited in Cologne at the Sonderbund exhibition where he was ranked with Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne. That year Munch had his first American exhibition In New York City. In 1913, the 50-year-old artist traveled extensively, had tributes paid to him, and rented larger quarters at Jeløya.

Munch turned to landscapes and large-scale art projects as he continued the murals for Oslo University which were, after lengthy controversy, finally accepted in 1914. Already a Knight of the Royal Order of St. Olaf since 1909, the Oslo National Gallery began buying some of Munch’s most important works – The Day After, Ashes, Puberty, Two Girls at the Verandah, and The Frenchman. The State museum received gifts from collectors as well. Olaf Schou (1861-1925) gave them Madonna, The Sick Child, Mother and Daughter, Girls on the Bridge and, later, The Scream, Death in the Sick Chamber, The Dance of Life, Girl at her Toilet, Betsy, Moonlight in Nice, and others.

Meanwhile, Munch decided to turn for inspiration to some of the outward obsessions of a new 20th century: its advancing technologies, mass media, high-speed transportation and urban life. 8

Edvard Munch, Bathing Men, 1907–1908, oil on canvas, 206 x 227.5 cm, Atheneum, Helsinki.

Edvard Munch, The Day After, 1894/5, oil on canvas, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Moonlight in Nice, 1895, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death in the Sickroom, 1893, pastel on canvas, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Girls on the Bridge,1899-1901, National Gallery, Oslo.

GLOBAL FAME, LAST EXHIBITIONS, OLD AGE AND DEATH

From 1914 until his death in January 1944, Munch sold nearly nothing but pictures bought by museums and new, commissioned work. Until then Munch had to sell pictures to live though he was reluctant and made replicas for himself. He did not sell works closely aligned to his emotional life. In 1916, Munch, now a famous artist, had finished the murals in the assembly Hall of Oslo University and purchased Ekely at Skøyen just outside the city. The artist constructed fences, let hedges and weeds grow tall, and closed off his residence to onlookers. Not strictly a misanthrope, Munch chose to live in glorious isolation. He hardly stayed in contact with family or relatives and permitted few friends to visit.

At Ekely Munch constructed interior and exterior studio spaces where, situated among works, Munch stored The Frieze of Life. At his death in January 1944 at Ekely, Munch bestowed all works in his possession to the city of Oslo– more than 1000 paintings, 15,000 prints, and about 500 watercolors and drawings. There was also some sculpture. These artworks comprise most of today’s Munch Museum – see https://www.munchmuseet.no/

In 1922 Munch painted 12 murals for a chocolate factory in Oslo. In the 1920’s and 1930’s he exhibited his art frequently— in Zurich, Basel, Berne, Berlin, Mannheim, Dresden. In 1936 and 1937, he exhibited in London, Amsterdam and Stockholm. There were major shows and retrospectives.

LAST PAINTINGS RETURN TO EARLIER DARKER SUBJECTS AND THEMES

Besides monumental work for public projects, Munch late paintings included almost genre-type scenes such as horses and workers in the field, fishermen, an elm forest, fruit trees and a garden. While the main mural for Festival Hall at Oslo University is mostly decorative, The Sun (1909-11) recalls aspects of Symbolism that Munch depicted in his darker pictures of the 1890s. Some late pictures stirred with the memory of past, darker experiences such as The Death of the Bohemian (1926) and The Bohemian’s Wedding (1926). In 1915 he painted a new version of the Death Struggle from 1895.

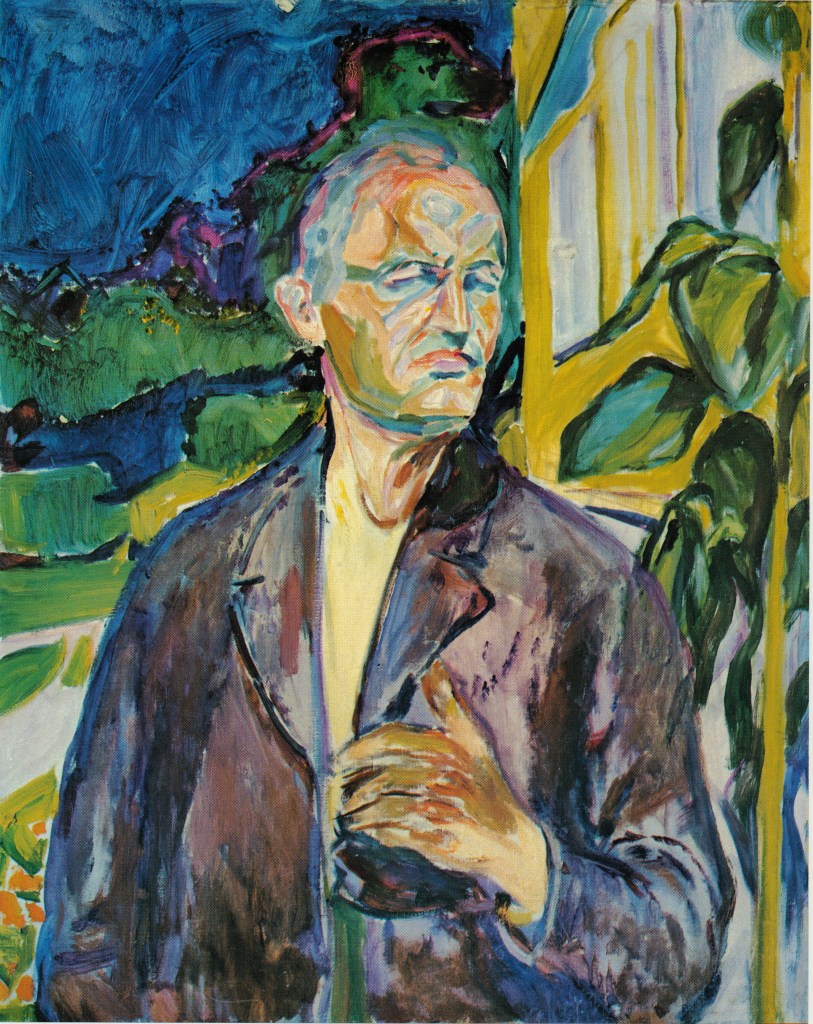

After contracting Spanish Flu in 1919, Munch painted his self-portrait as a convalescent from sickness and death. Twenty years later the artist painted a self portrait as an insomniac in The Night Wanderer (1939). Munch produced paintings and graphic work in great number. There are self-portraits; portraits; beach motifs; motifs from life of workers, fishermen, and farmers; garden scenes; nudes; landscapes; the theme of Faust, etc.

When Norway was invaded by Nazi Germany in April 1940 during World War II, Munch’s exhibitions outside Norway ceased by 1942. In 1937 the Nazis had labeled 37 of Munch’s paintings as “degenerate art” and they were removed and sold. After the invasion of Norway, Munch refused to have anything to do with the German occupiers. Munch stayed in Norway where he died at Ekely on January 23. 1944, at 80 years old.9

FOOTNOTES

1. Odilon Redon, To Myself, translated by Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman, New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1986, p. 23.

Quoted in Martha Kapos, The Post-Impressionists: A Retrospective, London: Beaux Arts Editions, 1993, pp. 175-180.

Jean Selz, Edvard Munch, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1974, p. 6 and 24

2. Sue Prideaux, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005, p. 2.

https://munch.emuseum.com/objects/5801/laura-munch – retrieved September 4, 2021.

3. Fra Kristiania-Bohêmen is a novel from 1885 by Norwegian writer Hans Jaeger.

J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p 41.

Sue Prideaux, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005, p. 35.

Jean Selz, Edvard Munch, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1974, p. 12

4. J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p 45 and p.50-52.

Arne Eggum, Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, , New York: C.N. Potter, 1984, p.61 and p. 305.

Jean Selz, Edvard Munch, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1974, p. 93.

Robert L. Delevoy, Symbolists and Symbolism, New York: Rizzoli, 1982, p. 100.

http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/worldwidemovements/hansjaeger.html -retrieved September 4, 2021.

5. Wolf-Dieter Dube, Expressionism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1972, p.157.

J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p .55; p. 61; p. 70. Pp. 51, 61, 70

Arne Eggum, Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, , New York: C.N. Potter, 1984, p.47 and p. 75.

Nancy Mowll Mathews, Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2001, p. 207.

Robert L. Delevoy, Symbolists and Symbolism, New York: Rizzoli, 1982, p. 98.

Robert Goldwater, Symbolism, New York: Westview Press, 1998, p.227.

Peter Paret, The Berlin Secession, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980, pp.79-80.

6. Arne Eggum, Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, , New York: C.N. Potter, 1984, p.10 and p. 152.

J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p 169.

https://theibtaurisblog.com/2012/08/06/the-graphic-works-and-prints-of-edvard-munch/ – retrieved September 4, 2021.

Jean Selz, Edvard Munch, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1974, pp. 18, 37, 45.

Philippe Jullian, Dreams of Decadence: Symbolist painters of the 1890s, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971. Pp 88-91

Michael Gibson, Symbolism, Cologne: Taschen, 1999, p.144.

Robert L. Delevoy, Symbolists and Symbolism, New York: Rizzoli, 1982, p. 97.

Rodolphe Rapetti, Symbolism, Paris: Flammarion, 2005.p. TBA

7. Robert Goldwater, Symbolism, New York: Westview Press, 1998, p.216. and 279.

J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p. 81; 88-89; 103; 123. .

https://www.nrk.no/urix/korrespondentbrevet-30.-mars-1.10964285 – retrieved September 3, 2021.

Arne Eggum, Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, , New York: C.N. Potter, 1984, pp. 196, 203, 228, 236.

Edward Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p. 189.

8. J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, pp. 127-128.

Sue Prideaux, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005, p. 373.

9. J.P. Hodin, Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972, p. 167.

Michael Gibson, Symbolism, Cologne: Taschen, 1999, p.149.

Munch, Langarred, Johan H., Revold, Residar, New York: Universe Books, 1964, p. i-ii; 1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bischoff, Ulrich, Edvard Munch 1863-1944, Cologne: Taschen, 2000.

Delevoy, Robert L., Symbolists and Symbolism, New York: Rizzoli, 1982.

Dube, Wolf-Dieter, Expressionism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Eggum, Arne, Edvard Munch: Paintings, Sketches, and Studies, New York: C.N. Potter, 1984.

Gibson, Michael, Symbolism, Cologne: Taschen, 1999.

Goldwater, Robert, Symbolism, New York: Westview Press, 1998.

Hodin, J.P., Edvard Munch, Thames & Hudson, 1972.

Jullian, Philippe, Dreams of Decadence: Symbolist Painters of the 1890s, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971.

Kapos, Martha, The Post-Impressionists: A Retrospective, London: Beaux Arts Editions, 1993.

Langarred, Johan H., Revold, Residar, Munch, New York: Universe Books, 1964.

Lucie-Smith, Edward, Symbolist Art, Thames & Hudson, 1972.

Mathews, Nancy Mowll, Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2001, p. 207.

Paret, Peter, The Berlin Secession, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Prideaux, Sue, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

Rapetti, Rodolphe, Symbolism, Paris: Flammarion, 2005.

Redon, Odilon, To Myself, translated by Mira Jacob and Jeanne L. Wasserman, New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1986.

Selz, Jean, Edvard Munch, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1974.

LIST OF WORKS BY EDVARD MUNCH

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, oil on canvas, 1886.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, crayon, 1893.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, Laura.

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, 1882, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Interior Pilestredet, oil on canvas, 1881, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Still Life with Jar, Apple, Walnut and Coconut, 1881, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, From Saxegårdsgate, c. 1882, oil on canvas, Lillehammer Art Museum.

Edvard Munch, Laura, 1882, oil on paper (top) and oil on cardboard, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Andreas Studying Anatomy, 1883, Oil on Cardboard, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Tête-à-tête, oil on canvas, 1885, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child (original version), 1885-86, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Hans Jæger, 1889, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Night on the Beach, 1889, Bergen Art Museum.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait, c. 1888, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Portrait of the Painter Jensen -Hjell, 1885, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Night In St. Cloud, 1890, oil on canvas, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening on the Karl Johan, 1889, oil, Bergen Art Museum.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the Window, 1891, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening Melancholy, 1891, oil, crayon, pencil on canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Rue Lafayette, 1891, oil on canvas, National Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Rue de Rivoli, 1891, oil on canvas, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, 1893, oil, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy (The Yellow Boat), 1891, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the window, 1892, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1892, oil, Private Collection.

Edvard Munch, The Girl by the Window, 1893, oil, Art Institute of Chicago.

Edvard Munch, Separation, 1893-94, Gouache, watercolor and crayon on paper, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Parting, 1894, oil on canvas, 67 x 128 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Three Stages of Women (Sphinx), c. 1894, Bergan.

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894–1895, oil on canvas, 151.5 x 110 cm, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Anxiety, 1894, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Despair, 1893, oil on canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Inger in Black and Violet, 1892, oil on canvas, National Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The storm, oil on canvas, 1893, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Edvard Munch, Summer Night’s Dream The Voice, 1893, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

Edvard Munch, Coastal Mysticism, 1892.

Edvard Munch, Sketch of the Model Posing, 1893, pastel on cardboard, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Edvard Munch, The Hands, 1893, oil on canvas, 91 x 77 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, At the Roulette Table in Monte Carlo, 1892, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait Under the Mask of the Woman, 1893, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait with Burning Cigarette, 1895, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait in Hell, c. 1895, oil on canvas, 82 x 60 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Stanislaw Przybyszewski,1895, pastel, 62x55cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, oil, tempera, pastel on cardboard, National Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1895. Ink.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, 1895, Dry-point and aquatint, 34.8 x 28 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Kiss, woodcut, n.d., 44.7 x 44.7. cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Jealousy, 1896, Lithograph, 46.5 x 56.5 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death and the Maiden, 1894, Dry-point, 30.2 x 22 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Melancholy (Evening),1896, woodcut, 37.6 x 45.5. cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Attraction, 1896, Lithograph, 47.2 x 35.5 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Sick Child, 1896, Lithograph, 42.1 x 56.5 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Evening, Melancholy I, woodcut, 1896.

Edvard Munch, Stéphane Mallarmé, 1896, lithograph.

Edvard Munch, Auguste Strindberg, 1896, lithograph.

Edvard Munch, Self-portrait, 1895, Lithograph, 45.5×31.7 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Edvard Munch, Lady From the Sea (detail), 1896, oil on canvas. 100 cm × 320 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Voice Summer Night, 1896, 90 cm × 119 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo

Edvard Munch, Paris Boulevard, 1896, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 130 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Inheritance, 1897-99, oil on canvas, 141 x 121 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Two people, 1899, oil on canvas, 175 x 143 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Amor and Psyche, 1907, oil on canvas, 118 x 99 cm

Edvard Munch, Marat’s death, 1907, oil on canvas, 151 x148 cm, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, The Murderess, 1906, Munch museum.

Edvard Munch, Death of Marat I, 1907, 150 x 199 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the Window, 1897, oil on canvas, 99 x 80.5 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death and the Maiden, 1893, oil on canvas, 128 x 86 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Man and Woman, 1898, oil on canvas, Bergen.

Edvard Munch, Stanislaw Przybyszewski (The Vampire), Oil and/or tempera on unprimed cardboard, 1893.

Edvard Munch, Weeping Nude, 1913–1914, 110 cm × 135 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait Against a Green Background and Caricature Portrait of Tulla Larsen, 1905.

Edvard Munch, Ashes, 1893,

Edvard Munch, The Dance of Life, 1899-1900.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1894, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, The Brooch, 1903, lithograph, 60×46 cm.

Edvard Munch, Salome, 1903, lithograph.

Edvard Munch, Fertility, 1898, woodcut, 42 x 51.7 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Women on the Beach, 1898, woodcut, 45.5 x 50.8 cm, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Red and White, 1899–1900, 93 cm × 129 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906, Thiel Gallery, Stockholm.

Edvard Munch, Red Virginia Creeper, 1900, oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm.

Edvard Munch, Young People on the Beach, 1902, oil on canvas, 90 x 174 cm.

Edvard Munch, On the beach, 1905, oil on canvas, 81x 121 cm.

Edvard Munch, Bathing Boys, c. 1904, oil on canvas, 194 x 294 cm.

Edvard Munch, Shore with Red House, 1904, oil on canvas, 69 × 109 cm, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Train Smoke,1900, 84 cm × 109 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, At The Sign of the Sweet Girl, 1907, oil on canvas, 85 x 130 cm.

Edvard Munch, Nude by the bed, c. 1907, oil on canvas, 120×121 cm.

Edvard Munch, Nude by the bed, c. 1907, oil on canvas, 120×121 cm.

Edvard Munch, Four Girls Åsgårdstrand, 1905, oil on canvas, 87x111cm.

Edvard Munch, Avenue in the snow, 1906, oil on canvas, 80 x100 cm.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with Brushes, 1904, 197×91 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine, 1906, 110 cm × 120, The Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Deathbed, 1900, oil on canvas, 100 x 110 cm.

Edvard Munch, Village Street, 1905, oil on canvas, 100×100 cm.

Edvard Munch, Prayer, 1902, woodcut, 45.8 x32.5 cm.

Edvard Munch, Dr. Daniel Jacobson, 1909, oil on canvas, 204 x 112 cm.

Edvard Munch, Nurse, 1909, dry point, 20.5×15.2 cm.

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910, oil, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait Bergen, 1916, oil on canvas, 90 x 60 cm.

Edvard Munch, Bathing Men, 1907–1908, oil on canvas, 206 x 227.5 cm, Atheneum, Helsinki.

Edvard Munch, The Day After, 1894/5, oil on canvas, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Moonlight in Nice, 1895, oil, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Death in the Sickroom, 1893, pastel on canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Girls on the Bridge,1899-1901, National Gallery, Oslo.

Edvard Munch, Mother and Daughter, 1897, Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, Madrid.

Edvard Munch, Crouching Nude, 1919, oil on canvas, Munch Museum.

Edvard Munch, Artist and his Model, 1919-1921, Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum, Madrid.