Feature Image: Two apostles, detail, Institution of the Eucharist window, F.X. Zettler, 1907-1910, St. Edmund Church. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

By 1910 F.X. Zettler’s mastery of the “Munich Style” – characterized by detailed scenes and vibrant colors on glass – made his German company one of the most popular designers in late 19th century and early 20th century American churches. These windows are religious paintings that are pedagogical as well as sacred images. The Roman Catholic Church teaches that Christ is “really present” in the Eucharist (a Greek word, eucharistia,that means “Thanksgiving”) and that his sacrifice on the cross on Calvary is repeated at every Mass as Christ gives His Body and Blood under the appearance or species of bread and wine in Holy Communion as food for eternal life. As parishes offer school children their first holy communion, Christ’s pose evokes that same event for the apostles. Accounts of the Institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper are in Luke 22, Mark 14, Matthew 26, and its significance explicated in John 6. It is recounted in Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, 11. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

Four apostles, detail, Institution of the Eucharist window, F.X. Zettler, 1907-1910, St. Edmund Church. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

In 2022, owing to continuously declining numbers in the church, St. Edmund Church at 188 S. Oak Park Avenue, Oak Park, IL, located close to the heart of its suburban downtown, was combined with another historic Oak Park parish, Ascension Church, at 808 S. East Avenue, about one mile to the south. Founded by Archbishop James Quigley (1854-1915) in June 1907, St. Edmund was the first Catholic parish in the village and one of the 75 new parishes founded by Quigley during his tenure between 1903 and 1915. James Quigley’s successor was Cardinal George Mundelein (1872-1939) who founded 80 more new parishes during his administration. Trying to fit into the longstanding predominantly Protestant community, St. Edmund was built in generous cooperation with its leading citizens and designed in a refined English neo-Gothic style. Evoking a low-profile parish country church, this kind of Catholic footprint would be imitated in other prosperous Chicago suburbs with strong Protestant roots well into the 20th century so to discreetly integrate into the community.

Most Rev. James Quigley, Archbishop of Chicago (1903-1915). In 1907 Archbishop Quigley traveled by car to Oak Park to attend the opening. Public domain.

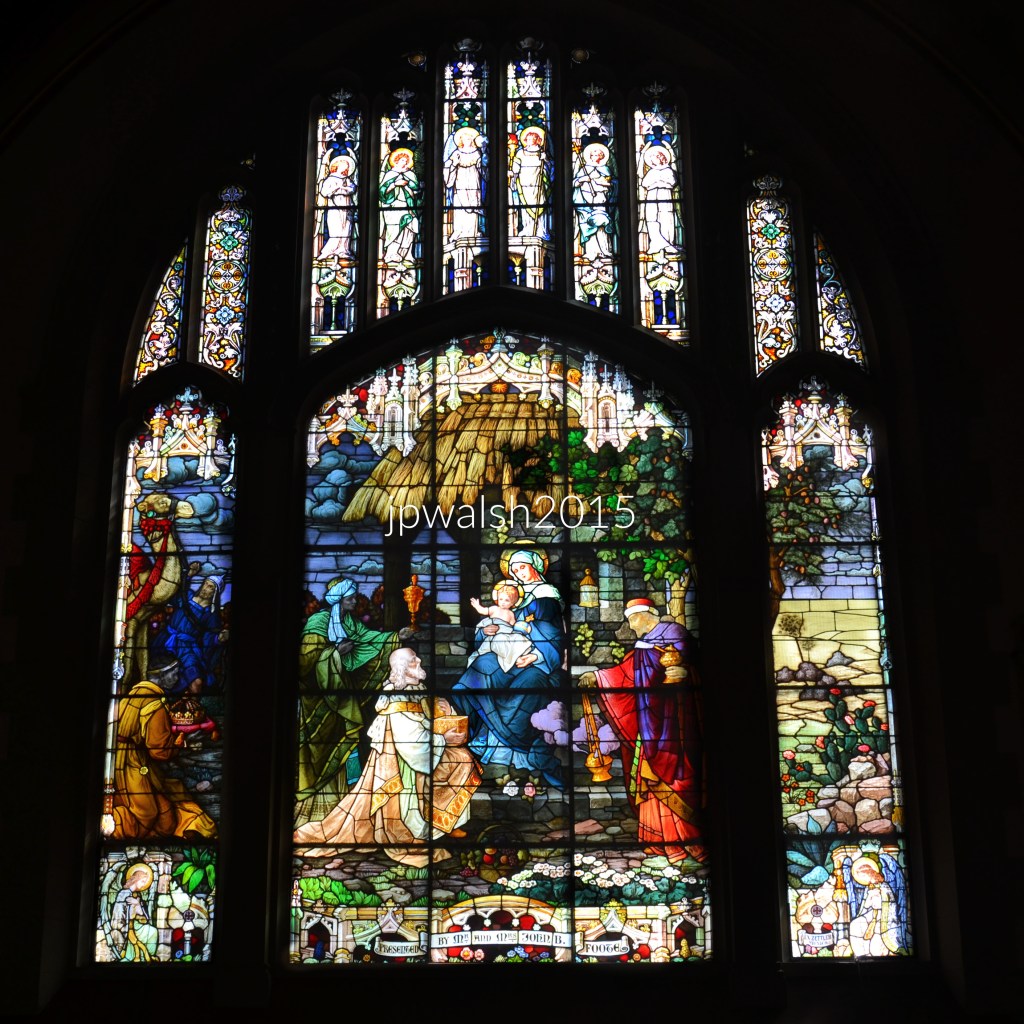

Since the mid-1980s reports from 2022 indicate a reduction by the Archdiocese of Chicago of more than 100 parishes from its nearly 450 parishes due to declining attendance and financial problems, of which St. Edmund is another example. It remains fortunate that this beautiful church building continues to exist and be used for worship. The English neo-Gothic style church was designed by prolific Chicago church architect Henry Schlacks (1867-1938) and dedicated in May 1910. The art glass windows were executed by the F.X. Zettler Studios of the Royal Bavarian Art Institute in Munich. Zettler also made mosaics such as at St. Anthony Church in Bridgeport also designed by Schlacks and consolidated first with All Saints parish and then both closed and combined with St. Mary of Perpetual Help. St. Edmund Church has undergone various mid-20th century redecorations that included the addition of paintings and marble upgrades for its altar, pulpit, and baptismal font designed by Chicago-based DaPrato Rigali founded in 1860. Exterior changes to the building were also made in the 1950’s replacing the church’s original red tiles for the roof and steeple to, respectively, slate and steel coverings.

St. Edmund Church, Oak Park, Illinois, dedicated in 1910, was designed in the late 19th century English neo-Gothic style. The later school (right), opened in 1917, was designed in the French neo-Gothic style. Both are the work of architect Henry Schlacks (1867-1938). Author’s photograph. September 2015.

St. Edmund Church, Oak Park, Illinois, part of the nave, transept and apse, south view. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

St. Edmund Church and school have been a work in progress. The school, a flamboyant neo-Gothic structure designed by Henry Schlacks, opened in 1917. During the post-war baby boom, additions to it were built in 1948 and 1959. In June 2016 the school closed. When the parish was young and growing with Catholic families, it purchased an architecturally significant private home in 1929 for the nuns who staffed the school. With post-Vatican II declining vocations of nuns and school enrollment, the convent was sold in the 1980’s. A 2000 renovation of the church included cleaning and restoring the stained-glass windows that portray scenes from the New Testament. In other Chicago churches with Zettler windows, such as, in St. Stanislaus Kosta Church in West Town, there are themes of the Rosary, while St. Adalbert, a Polish parish in Pilsen since closed by the archdiocese and sold for condo development, it was historic saints of Poland. Henry Zimach of HPZA was the architect of the St. Edmund renovation. In its first 49 years the church was led by one pastor: successful fundraiser Msgr. John H. Code. The next 49 years saw 6 pastors until the church had to combine with a nearby parish. Of the $100,000 construction cost for the church, one donor (Mrs. Mary Mulveil) donated half of it. From an operating expenses viewpoint this elite donor model is how even today some Catholic parishes across the Chicago region stay open. In 2026 one leading Catholic parish published tithing information that showed 95% of registered families do not tithe one dime and about a dozen families donate annually between $15,000 and $25,000 each. With pews half full, one can conclude that non-tithing families might not be at Sunday Mass either. With the Vatican discouraging any “pressure” on anyone, there’s little to no outreach by the parish to the vast majority of its wayward flock as long as apparently the affluent pay their church bills. Of course, if things really get untenable, the bishop then can simply decide to close one more parish.

Mid-20th century redecorations at St. Edmund Church included the addition of paintings and marble upgrades for its altar, pulpit, and baptismal font. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

These are religious paintings as they serve to teach the viewer by depicting scenes from the earthly episodes of Christ. But they are also sacred images, pure iconography, as they invite the viewer to contemplate and pray to those persons existing in the spiritual and heavenly domain with whom they are surrounded. Further, as Zettler’s stained glass are some of this church setting’s most spectacular art, they play a key role in aiding in worship. Individually and taken together, the gloriously colorful and drawn illuminating images accompany worshipers as they place them in the visual presence of the Trinity, the Blessed Mother, and the angels and saints and carry them upwards into their presence as they participate in the sacraments.

The Zettler windows in St. Edmund in Oak Park fill the church interior with the colorful light of glorious art that is both pedagogical and iconographical of the Biblical Catholic faith. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

German Art Glass.

Jesus healing the blind man (detail). This window presents healing stories such as found in John 9 (healing the blind man from birth), Mark 8 (healing a blind man at Bethsaida) and healings of two blind men in Matthew 9. The figure of a woman bending down to have her hair touching Jesus’ feet evokes Luke’s gospel (chapter 7) of the sinful woman who washes Jesus’ feet with her hair. The man at right carried by two others alludes to Jesus’s healing miracle of a man who could not walk found in Mark 2 and Luke 5. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

Zettler window of Jesus’s ministry of healing miracles. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

Zettler Window of Jesus calming the storm found in Luke 8, Matthew 8, Mark 4, and John 6. The event demonstrates the God-Man’s authority over nature. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

Nativity window found in Matthew and Luke. A dog in the lower left corner is one of many such animals scattered throughout Zettler’s windows in St. Edmund Church. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

The flight into Egypt window. Recounted in Matthew 2, the story relates how the Holy Family—Mary, Joseph, and infant Jesus—flee to Egypt to escape King Herod, who ordered the killing of young children to eliminate the prophesied King of the Jews. Joseph, warned by an angel in a dream, swiftly carried his family to Egypt, where they stayed until Herod’s death, fulfilling prophecy and symbolizing Christ’s presence in a world of darkness. The episode has long been a popular subject in Christian art, and Zettler depicts the episode focusing on the Holy Family’s determination under angelic protection. In popular piety, the event is one of the “seven sorrows” of Mary which she pondered in her heart. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

Above the entrance from the street to St. Edmund Church is a half circle stained glass window depicting Jesus as The Good Shepherd. Jesus calls Himself the Good Shepherd in John 10. Author’s photograph. September 2015.

WHO IS ST EDMUND OF CANTERBURY?

Nuremberg chronicles, Edmund, Archbishop of Canterbury (1493). Public Domain.

St. Edmund church in Oak Park is named for English saint Edmund of Canterbury (c. 1174–1240). Son of Edmund Rich, Edmund is also known as Edmund of Abingdon where he was born and made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1233 by Pope Gregory IX (1227-1241). History speaks of his parents as being practicing Catholics with his mother more fastidious and his father more laconic. Edmund, taking after his mother growing up, was considered a bit of a sanctimonious prig. Around the age of puberty, Edmund dedicated himself to the Blessed Mother and took a vow of perpetual chastity. When this vow of purity was later challenged by a young woman Edmund vigorously fought her back sufficiently that, as the young woman recalled, he called her “an offending Eve.” Edmund was educated in Paris but, starting around 1200, returned to Oxford to teach mathematics and philosophy in the circle of Stephen Langton (c. 1150–1228). In Edmund’s time, Langton was an influential English cardinal and Archbishop of Canterbury who participated in the political issues of his day including the Magna Carta crisis in 1215. Edmund is remembered at Oxford for building a Lady’s chapel with funds from his teaching stipend and passing much of his free time in prayer. The site where Edmund lived and taught became an academic hall at Oxford in his lifetime (1236) and remains today part of the college of St Edmund Hall, claimed to be the oldest surviving academic society to house and educate undergraduates in any university in the world. Notable alumni of St Edmund Hall include, at the time of posting, current British prime minister Keir Starmer.

Edmund studied theology between 1205 and 1210 and spent a year with the Augustinian canons of Merton Priory. Afterwards he became a priest and doctor of theology and would take frequent retreats at Reading Abbey in this period. Around 1219 and for the next 12 years the eloquent, learned and virtuous Edmund financed his education by serving as treasurer for Salisbury Cathedral, preached the Sixth Crusade in 1227 (a crusade which led to a shared Christian-Muslim governance situation in Jerusalem) and garnered several influential English friends.

In a mid-14th century manuscript, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (left) meets al-Kamil Muhammad al-Malik (right), whose negotiations led to shared Christian-Muslim governance in Jerusalem during the Sixth Crusade. Vatican Library. Public Domain.

In 1233, the 59-year-old was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Pope Gregory IX though the Canterbury chapter recommended several other candidates first. Accepting the position reluctantly, Edmund, consecrated on April 2, 1234, fought for independence of the English church from any foreign influence and this led to an episcopal tenure characterized by incessant and unseemly brawls with King Henry III and the papal delegation as the archbishop admonished the king for a government of baronial favoritism. Threatening the king with excommunication, the crown backed down temporarily but harbored enduring antipathy towards Edmund and looked for relief in Rome. In favor of strict discipline and truthful justice in civil and ecclesial government and life, coupled to a strong stance against any encroachment on the English church, including jealousy for his authorial rights to be enforced by litigation when necessary, the possibly soft spoken but clearly combative Edmund made for a very unpopular figure among the powerful and eventually led to his forced resignation in 1240. In 1236, with the object of freeing himself from Edmund’s control, the king requested a sympathetic legate from the pope who arrived to insult and contradict everything of importance Edmund chose to do and say in relation to current issues – from the marriage of Simon de Montfort and Henry’s sister Eleanor that Edmund found invalid, to Edmund’s own cathedral priests and monks who were opposed to Edmund’s rule. Edmund reacted to the opposition erratically, excommunicating at will, all of which was ignored by the pope who let his legate’s, and not Edmund’s, decisions stand which favored the king. Edmund was left to complain that the discipline of his national church was being undermined by the flaccid standards of world politics. Before thinking to resign, Edmund went to Rome in December 1237 to plead his cause in person before the pope. But already Henry III’s exactions and usurpations were backed up by the papal legate and Edmund’s mission was futile. Edmund returned to England in August 1238 where he was made to heel. Edmund resigned in 1240.

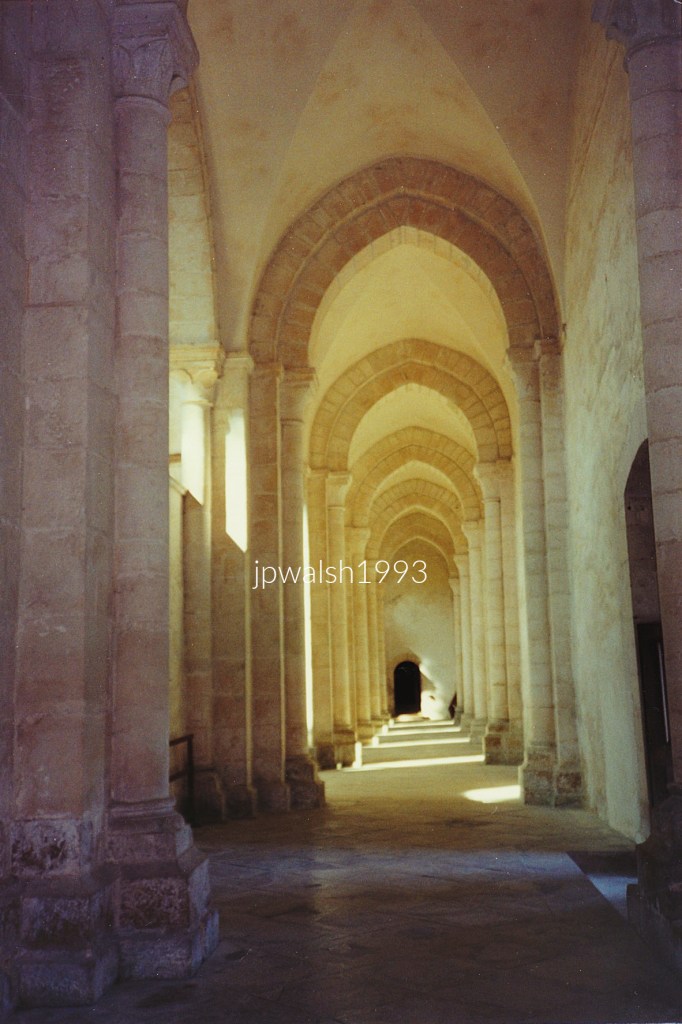

Abbey of Pontigny, view from south. The Cistercian abbey of Pontigny in France was a refuge for England’s persecuted archbishops, including Stephen Langton (c. 1150–1228), and Saints Thomas Becket (1120-1170) and Edmund of Canterbury (c. 1174–1240). Author’s photograph, September 1993.

At that juncture, Edmund set out for the Cistercian Abbey at Pontigny southeast of Paris in France, which had been a refuge for Edmund’s predecessors, Stephen Langton and Thomas Becket (1120-1170). The archbishop’s health soon gave way and, though Edmund decided to return to England, he died en route at Soisy-Buoy in the house of the Augustinian Canons on November 16, 1240.

Pontigny, north aisle, 12th century. At Pontigny St. Edmund of Canterbury led the life of a simple monk. Author’s photograph. September 1993.

Edmund’s remains were returned to the Abbey of Pontigny where he was buried and lies in state today in a reliquary above the high altar. Miracles were soon reported at Edmund’s tomb leading to his canonization by Pope Innocent IV in December 1246, making Edmund one of the fastest English saints to be canonized. When Blanche of Castile (1188 –1252) and King Louis of France (1214-1270) visited Pontigny, Edmund’s body was exhumed and shown to be incorrupt. His relics survived the French Revolution and when his tomb was opened again in 1849 his body, still incorrupt, had one arm found detached. This major relic was sent to the United States, where it is enshrined today on Enders Island off the coast of Mystic, Connecticut, inside the chapel of Our Lady of the Assumption at St. Edmund’s Retreat, run by the Society of Saint Edmund founded at Pontigny in 1843. Edmund’s life was one of self-sacrifice and devotion to others. From boyhood he practiced austerity and asceticism, fasting, and spending his nights in prayer and meditation. St. Edmund of Canterbury’s feast day is November 16.

St. Edmund of Canterbury, detail from the Westminster Psalter, mid-13th century, British Library. Public domain.

The Story of F.X. Zettler’s Royal Bavarian Art Institute.

About 100 miles south of Munich, Germany, was the home base of popular and well-regarded stained-glass studios such as Franz Mayer & Company and Zettler of which St. Edmund has a full coterie presented in this post. These photographs were shot by me in September 2015.

Franz Xavier Zettler was born in Munich, Germany in 1841 and worked as an ecclesial artist, founding his stained-glass design company after 1870, until his death in 1916. When he married Anna Mayer, Zettler married into another family of artisans, following a long tradition of artisans doing so. In 1848 Joseph Gabriel Mayer (1808-83) founded the Establishment for Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting (“Institute of Christian Art”) under the patronage of King Ludwig I of Bavaria (1786-1868). With royal commissions in Germany for the massive Cologne and Regensburg Gothic cathedrals as well as the Mariahilfkirche in Munich (Vorstadt Au) – the first German neo-Gothic church whose foundation was laid in 1831 – Mayer directed his son Franz Borgias Mayer, and son-in-law F. X. Zettler, to expand the establishment by including a division for stained glass in 1870.

King Ludwig I of Bavaria in Coronation Regalia (König Ludwig I. von Bayern im Krönungsornat) by Joseph Karl Stieler (1781-1858), 1826, oil on canvas, 96 x 67.3 in., Neue Pinakothek, Munich. see – Sammlung | König Ludwig I. von Bayern im Krönungsornat – retrieved January 14, 2026. Public domain.

Zettler’s company, the Bayerische Hofglasmalerei, enjoyed quick success with his award-winning windows displayed at the 1873 International Exhibition in Vienna. By 1882 Zettler’s firm was decreed as the “Royal Bavarian Art Establishment” by King Ludwig II (1845-1886). Almost immediately, these Munich and Austrian stained-glass companies had a profound relationship with immigrant Catholic churches in the United States as Zettler and the others, provided high quality glasswork that was familiar with Catholic piety and themes.

König Ludwig II. von Bayern als Hubertusritter (King Ludwig II of Bavaria as a Knight of Hubertus), Ferdinand Piloty d. J. (1828-1895), 1879, oil on canvas, 217,5 x 132,5 cm, Neue Pinakothek, Munich. See – Sammlung | König Ludwig II. von Bayern als Hubertusritter – retrieved January 14, 2026. Public domain.

After the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, these stained-glass companies sent representatives to Chicago to sell them on various stained-glass patterns from which to choose in a rebuild or renovation. Before the turn of the 2oth century, these large studios had set up branch offices in America, including Zettler’s, that catered to a booming church-building industry hungry for traditional pious art that had been the Catholic tradition since Ravenna and only slowed in the life of the church following Vatican II’s radical turn. Chicago and its environs particularly became a great center for this traditional German and Austrian made stained glass until just before the Great Depression. From the 1870s to the 1920s, Chicago became the most influential center of Catholic culture in the United States with German and Austrian stained glass, such as the Zettler windows in Saint Edmund Church in Oak Park, having the strongest reach. After 20 years, the predominance of these European glass companies was finally challenged in the last decade of the 19th century by an American company. Though Zettler won a top prize at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) gained notoriety with a display of his designed comprehensive collection in Art Nouveau style of jewelry, pottery, paintings, art glass, leaded-glass windows, lamps, and other decorative interiors that continued to gain in popularity, including in houses of worship, right up to World War II. A steep tariff imposed on imported stained glass in the United States after 1894 impacted some international art purchases though Catholic churches in particular continued to turn to German and Austrian glass for their workmanship and pious imagery taken from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. At some financial cost pastors believed that such traditional art aided their mostly immigrant congregation of professional and industrial factory-workers and their families in worship.

Zettler Studios was innovative in the perfection of the “Munich style” of windows, in which religious scenes were created in a process of painting and melting large sheets of glass in kiln heat. Zettler was also inspired by the German Romantic Nazarene art movement of the early 19th century whose artists rejected Neoclassicism to revive spiritual and religious-focused art of the Italian Renaissance. In Zettler’s array of religious figures depicted in stained glass windows his team used Italian Renaissance art principles of three-point perspective and line drawing that evoked realism in gestures, expressions and various garb.

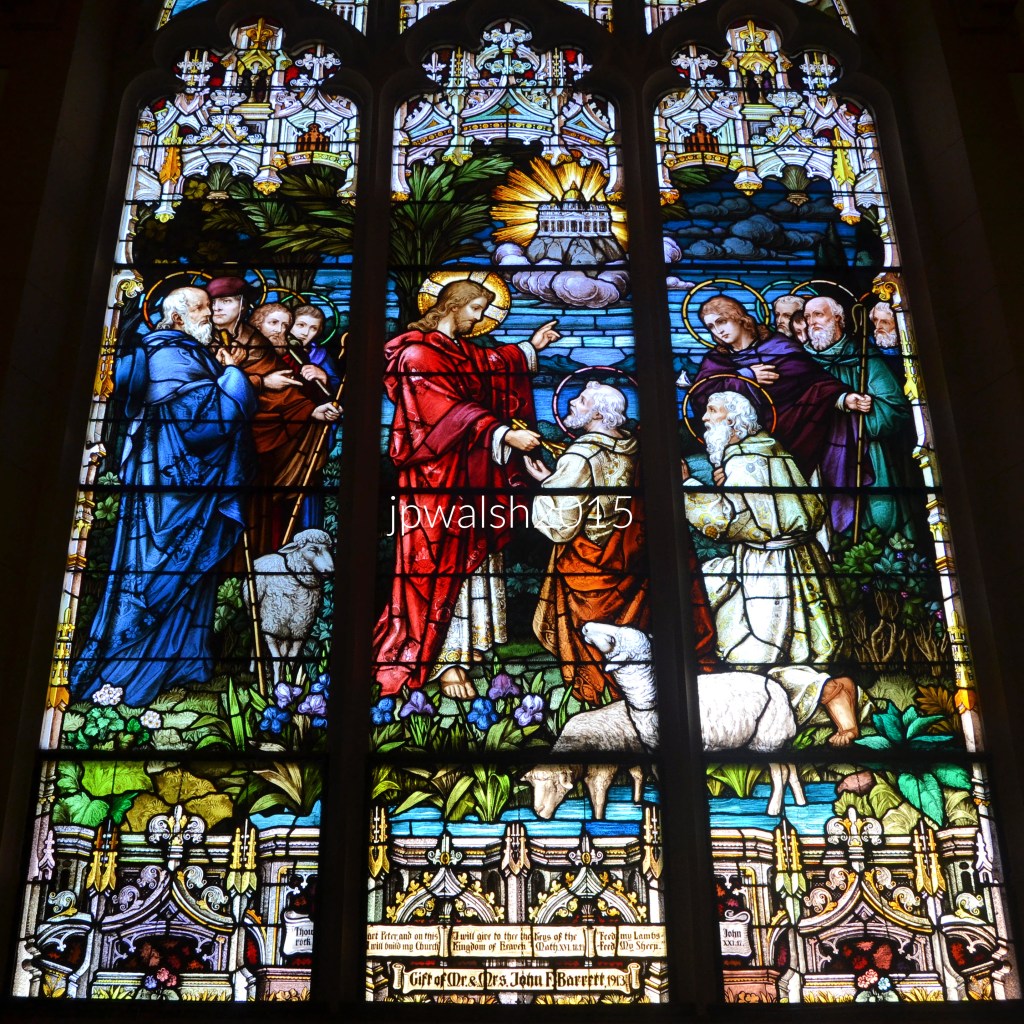

Jesus gives the Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven to Simon Peter.

Jesus asks, “Who do the people say I am?” leads to Peter’s confession of faith in Jesus as the Christ. it took place at Caesarea Philippi, a new city established by Philip the Tetrarch and was a Gentile community. The gospel writers usually show a lack of understanding of geography, but Matthew was better than Mark and in this incident the location is explicit and about a day’s journey on foot from Capernaum on the Galilee Sea where the disciples were first called. At this juncture in his mission Jesus lays down a challenge to his disciples and asks: Who am I? The story also appears in Mark and Luke and, again, there are differences with Matthew’s account. in Matthew Jesus calls himself by the title “son of man” (Mark and Luke have no title at that point) and Matthew adds Jeremiah to their common list of figures like John the Baptist and Elijah (Zeffirelli adds Ezekiel) that the people think Jesus is. it is “Simon Peter” that answers for the group: “You are the messiah.” Once again Matthew reflects a higher Christology, adding: “The son of the living God,” though the simpler statement is likely the original. These next verses are not in Mark or Luke. Jesus attributes Simon Peter’s confession to divine revelation (“for flesh and blood has not revealed this to you but my heavenly father”). Jesus Christ then elects Simon Peter to a new commission of authority with a new name. There is no other verse in the New Testament that explains Peter’s name change. It is clear Peter is the rock upon which the church is built as his commission from Christ. What is its precise or working sense as that foundation is mysterious. Peter is the rock because as representative and mouthpiece of the disciples he has gathered up and articulated their faith as a group. Jesus makes a bold claim that the group he has formed, the church, will endure as long as there is faith among them that he is the Messiah and that by that enduring faith “the gates of Sheol (the biblical abode of death) shall not prevail against it.” Giving Peter the keys at the establishment of the church following his confession of faith as representative of the disciples echoes Isaiah 22 and is a sure sign of royal power and authority that Jesus confers on Peter. This, as Jesus himself journeys to Jerusalem to his condemnation and crucifixion. Peter evokes the master of the palace, the highest officer in the Israelite royal court. The office of Peter is not as a caretaker or underling but master of the church (ecclesia) and the kingdom of heaven that scholars say here carries a similar meaning. Jesus bestows broad authority to Peter to “bind and loose” which is an obscure phrase with no biblical background but found in the role of rabbis who could impose and remove. Peter’s special position in the church is also made clear from other passages in the gospels as well as Acts of the Apostles. This confession of faith and charge of authority is followed by an instruction on the suffering of the Messiah, making this a crisis moment in the gospel narrative. Following miracles and wonders, the Suffering Messiah was entirely foreign to the Judaism of New Testament times and Matthew, Luke and Mark (the Synoptics) here briefly relate some of the early great disillusionment in the minds of the disciples at this point about the teacher which was never fully remedied until after the resurrection.

Keys of the Kingdom window, detail.

Jesus at the wedding feast of Cana (John 2). On the prompting of his mother, Jesus performed his first miracle of changing water into wine. The Blessed Mother was the primary catalyst in starting her son Jesus, living a hidden life for 30 years, to begin his public ministry.

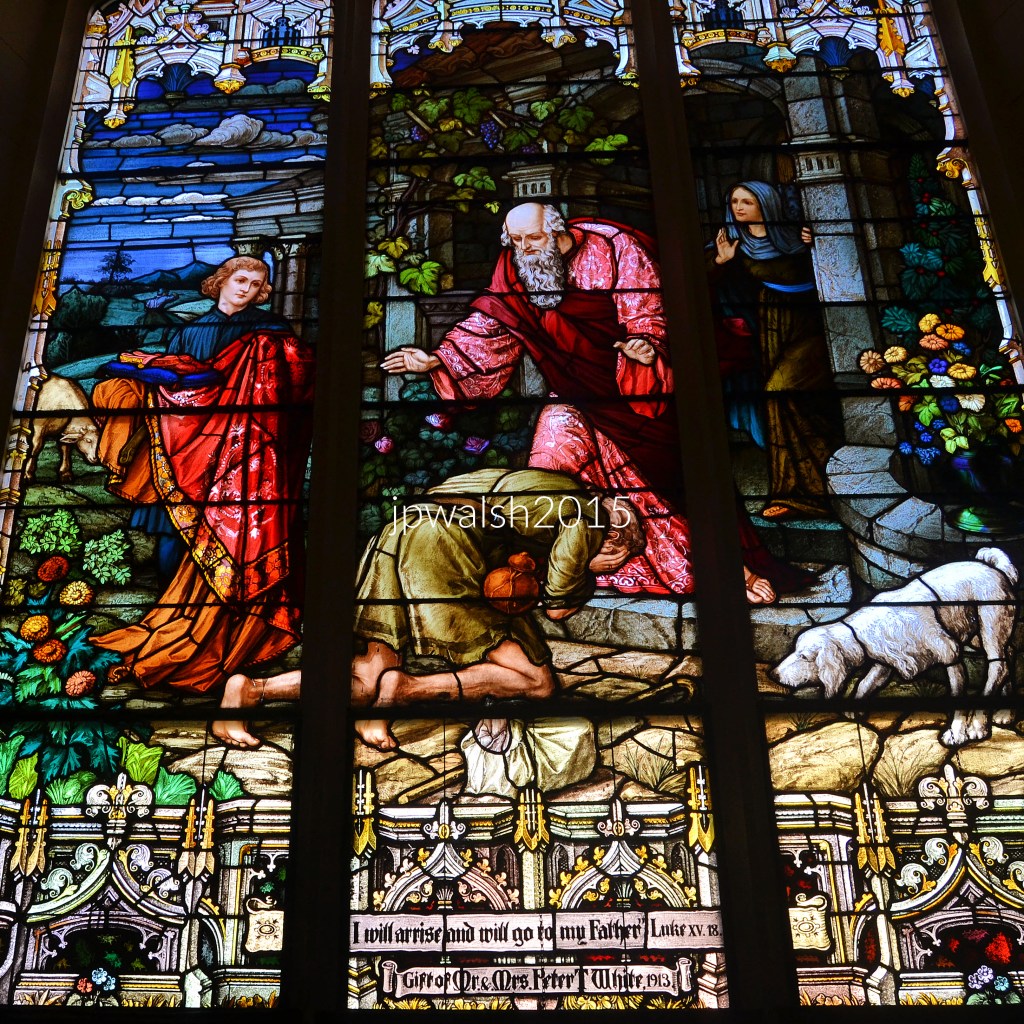

The Prodigal Son window. One of Jesus’ greatest parables, Luke 15 tells the story about a rebellious younger brother and son who demands from his father his share of the inheritance and proceeds to squander it on “riotous living” (Luke 15:13). He returns home destitute, asking only to be a servant in his father’s house, and finds instead that he is awaited, joyfully welcomed, and forgiven by his father, symbolizing God’s boundless love and restoration for repentant sinners. This is contrasted by the antagonist in the story – the self-righteous older brother who resents the celebration. He deems his repentant younger brother as an unredeemable trespasser and whose condemnation extends to this older brother’s envy of the prodigal’s special reception. The father reminds the older brother that “‘You are here with me always. Everything I have is yours” (Luke 15:31) and that it is right to especially celebrate the prodigal son’s return. For the father explains: “Your brother was dead and has come to life again. He was lost and has been found” (Luke 15: 32). Jesus’s parable teaches about sin, grace, and redemption, and the importance of unconditionally celebrating the return of the lost.

SOURCES:

First-ever Sacred Spaces House of Worship Walk in Oak Park this weekend – Wednesday Journal – retrieved January 13, 2026.

https://oprfmuseum.org/this-month-in-history/st-edmunds-parish-dedicates-new-oak-park-church – retrieved January 13, 2026.

Chicago Churches and Synagogues: An Architectural Pilgrimage, George Lane, S.J., and Algimantas Kezys, Loyola University Press, Chicago, 1981.

AIA Guide to Chicago, 2nd Edition, Alice Sinkevitch, Harcourt, Inc., Orlando, 2004.

Franz Xaver Zettler – Wikipedia – – retrieved January 13, 2026.

Ascension and St. Edmund Parish – Catholic Communities of Oak Park and Neighbors – Archdiocese of Chicago – Oak Park, IL – retrieved January 12, 2026.

Louis C. Tiffany Stained Glass Windows in Western New York – retrieved January 12, 2026.

Stained Glass Legacy – Ecclesiastical Sewing – retrieved January 13, 2026.

German Stained Glass in Buffalo – retrieved January 13, 2026.

Munich Mayer — Gelman Stained Glass Museum – retrieved January 13, 2026.

Zettler Stained Glass Window | Campus Crucifixes | University of Notre Dame – January 13, 2026.

The New Iconoclasm: What We’ve Forgotten – The Catholic Thing – retrieved January 14, 2026.

Saint Edmund Rich of Canterbury (1175-1240) – Find a Grave Memorial – January 14, 2026.

Our Lady of the Assumption Chapel – St. Edmund’s Retreat Inc. – Mystic, CT – retrieved January 14, 2026.

The New American Bible, Catholic Book Publishing Corp, New York, 1993.

The Saints: A Concise Biographical Dictionary, edited by John Coulson, Guild Press, New York, 1957, pp. 249-250.

CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Edmund Rich – – retrieved January 14, 2026.

Saint Edmund of Abingdon | Biography & Facts | Britannica – retrieved January 14, 2026.

The Jerome Biblical Commentary, edited by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., Joseph A Fitzmeyer, S.J., and Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1968.