FEATURE image: Hans and Sophie Scholl, painting —“Hans and Sophie Scholl, painting” by Ralf van Bühren is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

By John P. Walsh

On February 18, 1943, following the illegal distribution of anti-Nazi leaflets by the White Rose at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München—the leaflets instructing students and all others to actively resist the 10-year-old Nazi regime—three young German university students were arrested. In the next four days these students will be tried in a Nazi kangaroo court, convicted of treason, and condemned to death. Their crime?—public vocal resistance to the totalitarian state that suppresses freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of conscience in addition to reprehensible war crimes, including the Holocaust, during World War II.

On February 22, 1943, in Stadelheim Prison in Munich, Germany, these three White Rose resisters are the first of their group to die for freedom and whose legacy in the 21st century is to be listed as some of the most important Germans of all time—namely, 21-year-old Sophie Scholl, her brother, 24-year-old Hans Scholl, and 23-year-old Christoph Probst, a married father with three children.

Christoph Probst: It wasn’t in vain.

Sophie Scholl: The sun is still shining.

The execution scene from Marc Rothemund’s 2005 German film, Sophie Scholl – The Final Days (“Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage”). On February 22, 1943 the three condemned White Rose students—Sophie Scholl (Julia Jentsch), Christoph Probst (Florian Stetter) and Hans Scholl (Fabian Hinrichs)—are allowed a final moment together before being beheaded in Munich’s Stadelheim Prison.

By the start of 1943, the Nazis were badly losing the Battle of Stalingrad in Russia that had been raging since August 1942. Its outcome was a major turning point in the war. The German armed forces experienced nearly one million casualties in six months. The American, British, and the Russian armed forces were closing in on Hitler’s Third Reich from many sides.

Since June 1942 five anti-Nazi leaflets had been written and distributed in and around the university in Munich. The distribution channels as well as the network of this new clandestine anti-Nazi group—who eventually called themselves the German Resistance Movement, a.k.a. the White Rose—had steadily expanded during the creation of these leaflets.

Conditions were growing tense in Germany. There was a developing global consensus—that included some even in Germany— that Hitler’s war was ultimately unwinnable for the Fascist tyrant. As these totalitarian thugs had lashed out to consolidate power so, as ultimate military victory was slipping away, the regime stooped to any means to crush its internal enemies.

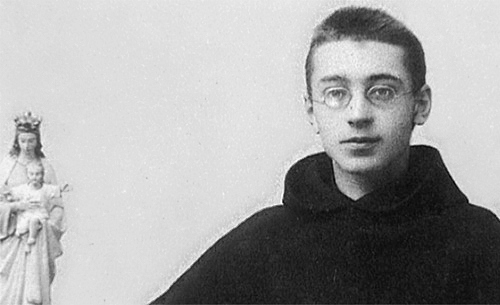

Sophie Scholl, May 9, 1921-February 22, 1943.

Sophie Scholl had almost not graduated from high school in May 1940 because she was sick and tired of the curriculum’s relentless political (Nazi) indoctrination. Scholl was fond of children and took a job teaching kindergarten. But her motivation was not simply that she had found an early vocation but hoped to steer clear of Germany’s six-month National Labor Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst).

The Nazis found her anyway— and Sophie taught at a National Labor Service-approved nursery as part of the war effort. Scholl might not have bothered with the National Labor Service at all except that the Nazis had set it up as a prerequisite for attending university.

In her personal reading Sophie Scholl had already developed an interest in philosophy and theology and wanted to pursue these subjects academically. The Labor Service experience did contribute, however, to Sophie’s outlook—she reacted completely against its militaristic aspects to the point where she started to practice forms of nonviolent resistance.

1940 Letter from Sophie Scholl to a Friend – White Rose Memorial Room – Interior of Main Building of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany.

In May 1942, 21-year-old Sophie started at the University in Munich. Her older brother Hans, studying medicine and philosophy at the school, introduced his younger sister to all his friends. Though Hans had evolving and increasingly strong anti-Nazi views, as did his friends, camaraderie revolved around the arts, music, philosophy and theology. The Scholls were also physically active—especially hiking and swimming.

Sophie pursued her intellectual interests at the university making connections with artists, writers, and philosophers. Her father, a hometown mayor, had been put in prison for an indirect critical remark he made about Hitler—and Sophie’s quest to understand how she, as an individual, should act under a dictatorship was intensely personal.

The White Rose formed and began writing and publishing anti-Nazi leaflets in June and July 1942—but Hans Scholl kept his dangerous undertaking secret from Sophie. But, in November 1942, when Sophie learned about the White Rose, she immediately joined.

Hans Scholl (Fabian Hinrichs), left, and Sophie Scholl (Julia Jentsch) in the 2005 German historical film, Sophie Scholl – The Final Days.

On February 18, 1943, in the wake of the battle of Stalingrad, and major Allied victories in Africa which had the Americans and British closing in on Hitler’s Europe, the sixth and final leaflet produced by the White Rose was distributed by Hans and Sophie Scholl and others of the White Rose at Munich University. The leaflet had been written by Kurt Huber, a university faculty and White Rose member, and stated that the “day of reckoning” had finally come for “[Hitler,] the most contemptible tyrant that the German people has ever endured.”

The Atrium, Munich University, where the Scholls dropped the sixth leaflets on February 18, 1943, which led to their arrest by the Gestapo.

Atrium, Munich University.

Bringing the leaflets in suitcases, the Scholls stacked them in corridors of the main building—and the hurried activity, including tossing the last leaflets into the atrium, was noticed by a maintenance man who reported it. Before their arrest by the Gestapo, Sophie had successfully gotten rid of any incriminating evidence. But the Gestapo did find fragments of a seventh leaflet by Christoph Probst on Hans Scholl’s person and, upon searching the Scholls’ apartment, confirmed the White Rose writings. The Gestapo was going to let Sophie free, but when she discovered her older brother had been arrested, she confessed to her full role.

Hans and Sophie Scholl lived in the rear of this apartment building at 13 Franz-Joseph Strasse in Munich from June 1942 until their arrest on February 18, 1943 and execution on February 22, 1943.

Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst.

During the interrogation following her arrest, transcripts show that Sophie defended herself mainly by claiming her right to act based on an individual “theology of conscience.”

On February 22, 1943, the Scholls and Christoph Probst were tried in the Volksgerichtshof (The People’s Court) before rabid Nazi judge Roland Freisler. Sophie interrupted the judge several times during his tirades. The court record shows her saying to the judge: “Somebody—after all—had to make a start. What we wrote and said is believed by many others. They just don’t dare to express themselves as we did.” The trio were found guilty of treason and condemned to death. They were guillotined the same day at Munich’s Stadelheim Prison.

Sophie Scholl, Hans Scholl and Christoph Probst, a married father of three children, were tried in the Volksgerichtshof (The People’s Court) before the rabid Nazi judge Roland Freisler. Transcripts show Sophie told the judge, Somebody—after all—had to make a start. What we wrote and said is believed by many others. They just don’t dare to express themselves as we did.

White Rose stamp – Sophie and Hans Scholl.

Hans Scholl was, with Alexander Schmorell (1917-executed by the Nazis in prison, July 13, 1943), a founding member of the White Rose in 1942. After serving as a medic on the Eastern Front in 1939, Hans Scholl became determined to do something to change the German people’s minds about the Nazi regime and its war effort.

By June 1942 the White Rose (Weiße Rose) had been founded on principles of nonviolent intellectual resistance to the Nazis—a highly dangerous proposition in a totalitarian regime.

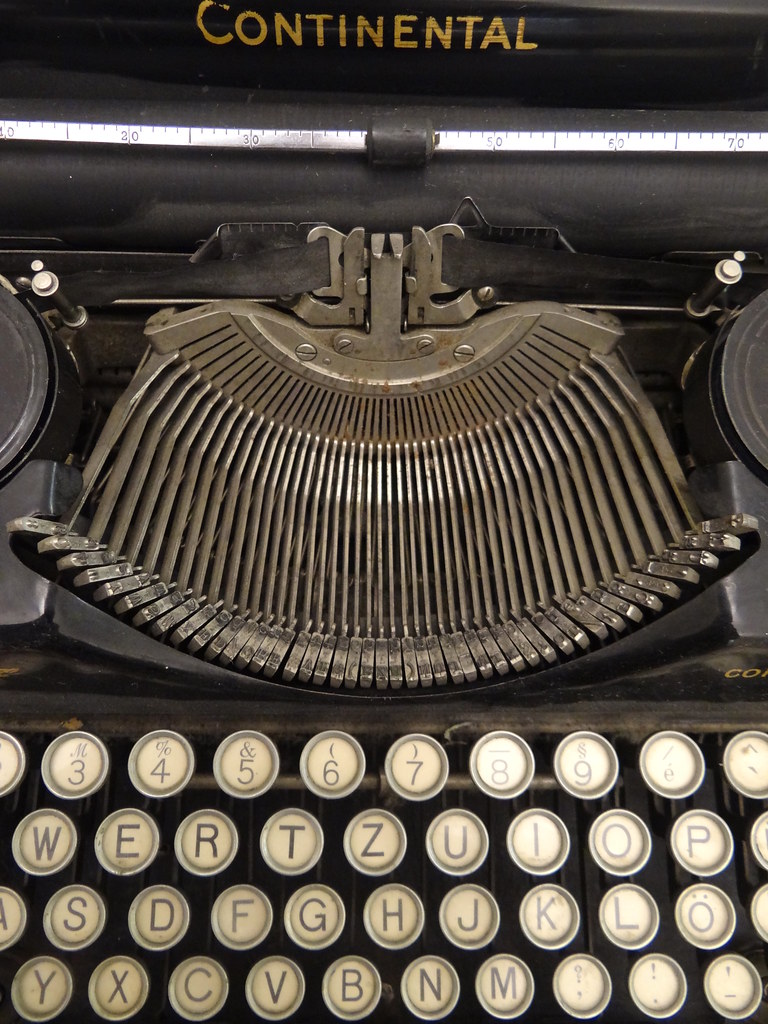

Detail of Typewriter Used to Produce White Rose Anti-Nazi Leaflets – White Rose Memorial Room – Interior of Main Building of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany.

Between June and mid-July 1942, Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell wrote four leaflets against the Nazis appealing to the truth of the people’s consciences based on facts. “Isn’t it true that every honest German is ashamed of the government these days?’ the writers asked in their first leaflet. “Who among us has any conception of the dimensions of the shame that will befall us and our children when one day the veil has fallen from our eyes and the most horrible crimes reach the light of day?”

Alexander Schmorell was, with Hans Scholl, a co-founder of the White Rose. Schmorell co-wrote their leaflets. A Russian-German student at Munich University, Schmorell was sentenced to death at 25 years old on April 19, 1943 at the second trial of the White Rose at the Volksgerichtshof. With Munich University faculty member Kurt Huber, also a White Rose member and leaflet writer, Schmorell was beheaded at Munich’s Stadelheim Prison on July 13, 1943. In 2012, Schmorell was declared a saint and martyr in the Russian Orthodox Church.

In the second leaflet the White Rose spoke of the crimes of the Holocaust: “Since the conquest of Poland, 300,000 Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way…The German people sleep in a stupid sleep and encourage the Fascist criminals…”

The third leaflet appealed to the German people’s “spirit” to eliminate the Nazi system in their midst.

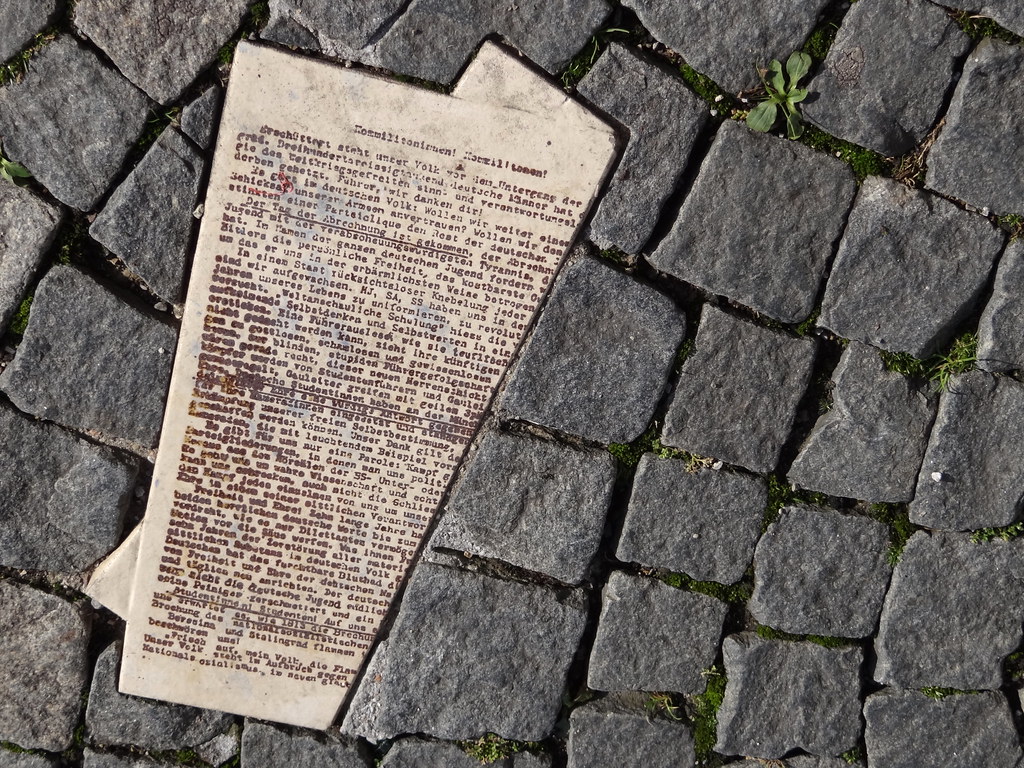

Leaflets, Memorial to Scholls at Munich University.

For the next four months, until November 1942, Scholl, Schmorell, and other young members of the White Rose were drafted to again serve as medics on the Eastern Front. War’s ongoing horrors that they witnessed only strengthened their resolve to resist.

At their return to Germany in autumn 1942 Sophie Scholl, Hans’ younger sister (born May 9, 1921), learned about the White Rose and Hans’ involvement in it, and eagerly joined the group.

Sophie Scholl bust, Munich University.

With the Battle of Stalingrad raging since August 1942, the White Rose (now called the German Resistance Movement) produced a fifth leaflet in January 1943. It was an appeal addressed to all Germans and the White Rose made almost 10,000 copies to distribute. The leaflet presented a straightforward analysis of the situation so to jog people’s intellect to take moral action. To state, as the leaflet did, that “Hitler cannot win the war; he can only prolong it.” was pure heresy to the all-encompassing propaganda arm of the dictatorship.

In the Battle of Stalingrad which the Nazis lost—it was the major turning point in the war—Hitler made an intense appeal to the German people’s patriotism. By one count, the German armed forces experienced nearly one million casualties in about six months.

The German populace—as well as people around the world– understood that Hitler’s defeat was inevitable. But, unlike the Americans and British who, in November 1942, successfully began and concluded Operation Torch in French Morocco pushing the Germans east and out of North Africa and next out of Southern Europe, few Germans were willing to even yet criticize the Nazi regime let alone take action as did the handful of young students and faculty of the White Rose.

White Rose Leaflets, memorial.

The White Rose’s fifth leaflet called all Germans to “Support the resistance movement!” The leaflet labeled Nazi policies as racist and subhuman, imperialist and militarist—and to be resisted. But further, a future Germany and Europe must, stated the White Rose in this penultimate leaflet, protect “freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the individual citizen from the arbitrary action of any dictator states.”

It was in January 1943 that the White Rose was beginning to expand its operation to make connection with older anti-Nazi groups already formed and operating in Germany, such as the Kreisau Circle led by Helmuth James von Moltke (1907-executed by the Nazis in prison, January 23, 1945).

Helmuth James Graf von Moltke (1907–1945) was one of the leaders of an early diverse group of anti-Nazi intellectuals known as the Kreisau Circle. In prison since January 1944, Von Moltke is photographed at his trial in July 1944. The Nazis executed Moltke in prison in January 1945. By early 1943, members of the mostly student-led White Rose were starting to expand their network of contacts to include other anti-Nazi groups such as the Kriesau Circle.

With the defeat at Stalingrad officially announced by the Nazis in early February 1943, the totalitarian regime blamed the German people. This included pointing a finger at university students as unpatriotic who did not serve in the army. Such slanderous and cowardly accusations from Nazi leaders who pompously impugned German intellectual youth in the wake of a massive Hitler-led military defeat making for one million casualties and devastating the nation’s morale, sparked a riot by students at the university in Munich. A growing chaos under the totalitarian regime had a heartbeat—and as in all totalitarian regimes, scapegoats must be found and made examples of. The leaflets of the White Rose had been disseminating anti-Nazi literature since June 1942. Its perpetrators had yet to be found out—and stood square at the tip of the Fascist dictatorship’s spear.

The White Rose, its members actively looking to capitalize on the energy of the students’ righteous indignation, decided to send out their sixth and last leaflet—which they did on February 18, 1943. The sixth leaflet, written by Munich faculty Kurt Huber (1893-executed by the Nazis in prison, July 13, 1943), and revised by Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell, said that with “the dead of Stalingrad [to] adjure us!,” the “day of reckoning” had finally come for “[Hitler,] the most contemptible tyrant that the German people has ever endured.” The group also stenciled slogans on university walls and buildings throughout Munich, the Nazi Party’s home base, stating “Down with Hitler!” and “Freedom!”

Munich University, Main Corridor.

The distribution of the leaflets packed in suitcases—this time including the public participation of Sophie Scholl—took place on Thursday, February 18, 1943. It is what led to the arrest, trial, conviction, and execution by beheading of Hans and Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst by the Nazis within the span of the next four days.

Sophie Scholl’s last words were: It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days? How many young, promising lives? What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted? Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt!

Hans Scholl’s last words were Es lebe die Freiheit! (Let Freedom live!)

Christoph Probst, Hans and Sophie Scholl graves, Perlach Cemetery in Munich.

Scholl graves, Perlach Cemetery, Munich.

PHOTO CREDITS–

Hans and Sophie Scholl, painting —“Hans and Sophie Scholl, painting” by Ralf van Bühren is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Sophie Scholl” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“1940 Letter from Sophie Scholl to a Friend – White Rose Memorial Room – Interior of Main Building of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“White Rose film” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Atrium, Munich University” by Alex J Donohue is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Atrium, Munich University” by Alex J Donohue is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“13 Hans Joseph Strasse, Munich” by Alex J Donohue is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Sophie Scholl and Christoph Probst–“The White Rose” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Sophie Scholl on trial – film” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“White Rose stamp – Sophie & Hans Scholl” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Detail of Typewriter Used to Produce White Rose Anti-Nazi Leaflets – White Rose Memorial Room – Interior of Main Building of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“White Rose Public Memorial – Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany – 05” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Leaflets memorial for Hans and Sophie Scholl” by Alex J Donohue is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Sophie Scholl bust, Munich University” by Alex J Donohue is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“White Rose Movement Public Memorial – Geschwister-Scholl-Platz – Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany – 01” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“File:Bundesarchiv Bild 147-1277, Volksgerichtshof, Helmuth James Graf v. Moltke.jpg” by Unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

“Interior of Main Building of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany – 01” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

white flowers/leaflets–“White Rose Movement Public Memorial – Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat – Munich – Germany – 02” by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Probst–“Hans and Sophie Scholl graves, Perlach Cemetery in Munich” by Dage – Looking For Europe is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“Hans and Sophie Scholl graves, Perlach Cemetery in Munich” by Dage – Looking For Europe is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Frieheit–“Hans and Sophie Scholl graves, Perlach Cemetery in Munich” by Dage – Looking For Europe is licensed under CC BY 2.0