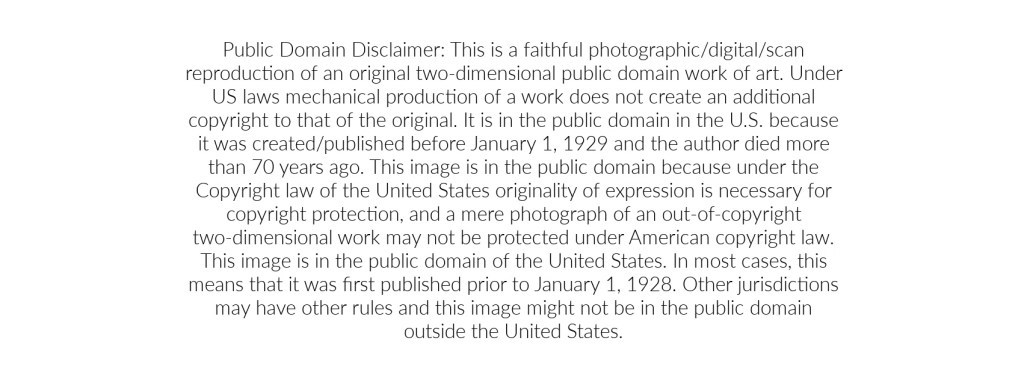

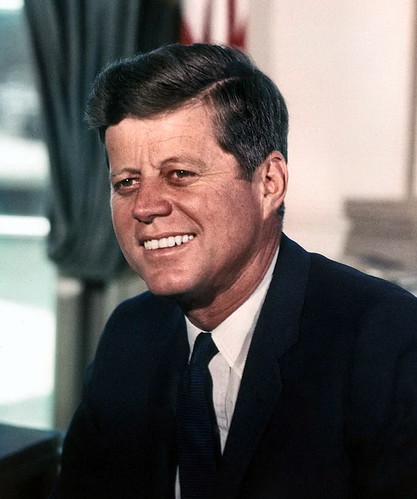

FEATURE image: Portrait of President John F. Kennedy. “President John F. Kennedy” by U.S. Embassy New Delhi is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

INTRODUCTION.

by John P. Walsh

I think – and I am sure this is the view of the people and the states- the right to vote is very basic. If we are going to neglect that right, then all of our talk about freedom is hollow. And therefore we shall give every protection that we can to anybody who is seeking the vote. News conference, September 13, 1962.

The men who create power make an indispensible contribution to the nation’s greatness. But the men who question power make a contribution just as indispensible for they determine whether we use power or power uses us. Remarks at Amherst College, October 26, 1963.

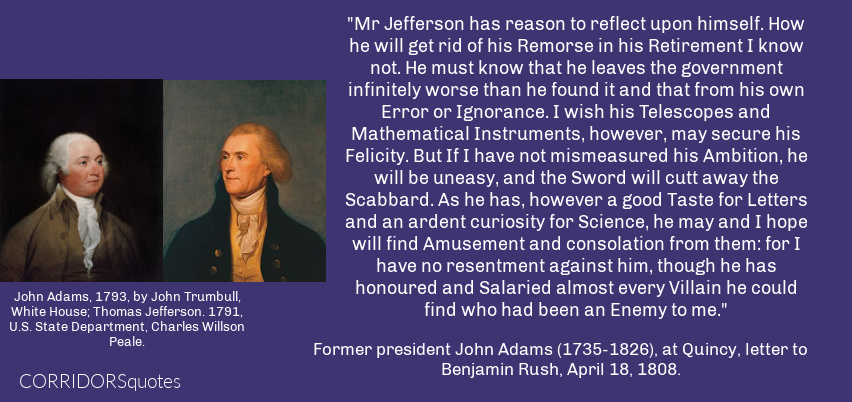

One of the rare joint appearances of Senators John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, the Democratic Presidential ticket, during the 1960 campaign which they prevailed over the Republican ticket of Nixon-Lodge. Here the two men make a joint campaign appearance in Grand Prairie, Texas, in September 1960. Kennedy nor Johnson were natural campaigners—Kennedy’s hands would be shaking hidden under a table or podium as he spoke, his voice growing hoarse. Johnson, who was uncomfortable in crowds and tried too hard, often worked himself on the campaign trail into a sick exhaustion.

Though both candidates wanted to have more joint appearances on the campaign trail, both senators’ aides mutually agreed it mostly hurt the ticket’s—and more precisely, Kennedy’s —image. Though Johnson was only nine years older than Kennedy—both men were the first U.S. presidents born in the 20th century— aides believed that wherever they showed up together Kennedy looked as if he might be LBJ’s son. However, the press and LBJ griped for weeks and months that the candidates should make more joint campaign appearances running as they were for the highest offices in the land.

When it was hinted in the press that there was a growing rift between the candidates and that that was to blame for their not campaigning together, another joint appearance of JFK and LBJ was scheduled in November 1960 five days before Election Day. For the campaign event at the Biltmore in Los Angeles Lyndon Johnson flew out especially to be there and the event received glowing national print and television coverage. On that Thursday before the Tuesday when Americans went to the polls, both candidates and their campaigns viewed the event as a big plus.

Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer. Let us not seek to fix the blame for the past. Let us accept our own responsibility for the future. Speech at Loyola College Alumni Banquet, Baltimore, Maryland, February 18, 1958.

Above: Rev. Dr. Michael Ramsey (1904-1988), Archbishop of Canterbury, and JFK, met on Halloween in 1962. Their Wednesday meeting took place just 3 days following the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The world breathed a great sigh of relief that armed confrontation which likely would lead to nuclear war between superpowers was avoided. The previous Saturday, October 27, 1962, was in fact one of the tensest days in the entire ordeal. A U-2 plane was shot down by Soviet-supplied SAM missiles. They killed the USAF pilot and Kennedy’s own ExCOMM demanded immediate military action against those sites. Kennedy resisted the advice. Upon shooting down and killing the U.S. pilot, the Soviets demanded tougher terms for negotiating the removal of 42 mid and long-range nuclear missiles in Cuba. That night, Robert Kennedy met secretly with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin in Washington, D.C. where they reached a basic understanding that only needed approval by Moscow. The next morning. Sunday, October 28, 1962, Radio Moscow announced that the Soviet Union had accepted Kennedy’s proposed solution. The 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis was over. Michael Ramsey was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury on May 31, 1961, and installed in June 1961. He served in this position until 1974. In 1962 Dr. Ramsey was then serving as president of the World Council of Churches (1961 to 1968) and, during his archbishopric, the first woman Anglican priest – Chicago-born high altitude balloonist Jeannette Piccard (1895 -1981) – was ordained in the United States in 1974.

This nation was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened. Televised address to the nation on Civil Rights, June 11, 1963.

SPEAKING OF FREEDOM OF INFORMATION IN A FREE COUNTRY TO THE ENTIRE WORLD. Voice of America speech, February 26, 1962. FULLER CONTEXT: “What we do here in this country, and what we are, what we want to be, represents really a great experiment in a most difficult kind of self-discipline, and that is the organization and maintenance and development of the progress of free government. And it is your task, as the executives and participants in the Voice of America, to tell that story around the world.

This is an extremely difficult and sensitive task. On the one hand you are an arm of the Government and therefore an arm of the Nation, and it is your task to bring our story around the world in a way which serves to represent democracy and the United States in its most favorable light. But on the other hand, as part of the cause of freedom, and the arm of freedom, you are obliged to tell our story in a truthful way, to tell it, as Oliver Cromwell said.. with all our blemishes and warts, …And we hope that the bad and the good is sifted together by people of judgment and discretion and taste and discrimination, that they will realize what we are trying to do here.

This presents to you an almost impossible challenge, ..The first words that the Voice of America spoke were [IN 1942]. They said, “The Voice of America speaks. Today America has been at war for 79 days. Daily at this time we shall speak to you about America and the war, and the news may be good or bad. We shall tell you the truth”…

In 1946 the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution reading in part, “freedom of information is a fundamental human right, and the touchstone of all the freedoms to which the United Nations is consecrated.” This is our touchstone…We seek a free flow of information across national boundaries and oceans, across iron curtains and stone walls. We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.

The Voice of America thus carries a heavy responsibility. Its burden of truth is not easy to bear. It must explain to a curious and suspicious world what we are. It must tell them of our basic beliefs. It must tell them of a country which is in some ways a rather old country–certainly old as republics go. And yet it must make our ideas alive and new and vital in the high competition which goes on around the world since the end of World War II.

…The advent of the communications satellite, the modernization of education of less-developed nations, the new wonders of electronics and technology, all these and other developments will give our generation an unprecedented opportunity to tell our story. And we must not only be equal to the opportunity, but to the challenge as well. For in the next 20 years your problem and ours as a country, in telling our story, will grow more complex. …

We believe that people are capable of standing the burdens and the pressures which choice places upon them, …And as you tell it, it spreads. And as it spreads, not only is the security of the United States assisted, but the cause of freedom.” See – https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-20th-anniversary-the-voice-america – retrieved May 29, 2025.

Report to the American People on Civil Rights – June 11, 1963.

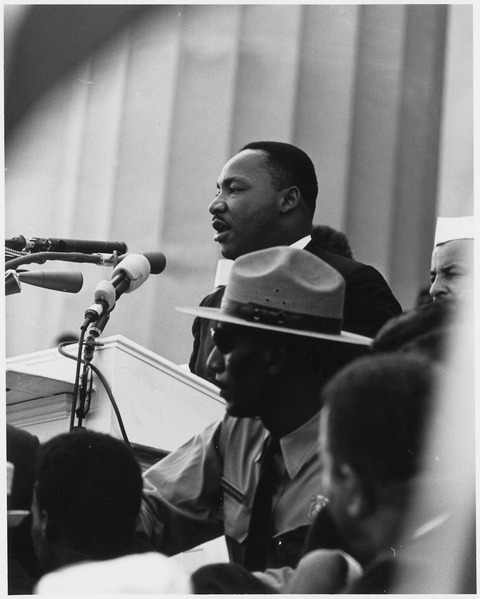

June 11, 2025 – (13.23 minutes). On May 27, 1963 the Supreme Court stated that it was not going to tolerate the evasion of its 1954 landmark decision Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools. They stated such in another desegregation case involving public parks. When the High Court made their decision in 1954, in no way could they have foreseen the years of delay. On June 5, 1963 a federal court enjoined Alabama Gov. George Wallace from in any way impeding the admission of two qualified Black citizens from enrolling in the University of Alabama. President John F. Kennedy, on June 10, 1963, reinforced this decision by writing to Gov. Wallace urging him not to interfere. The following day, June 11, 1963, Wallace carried out his pledge to “stand in the schoolhouse door” and blocked the Black students from enrolling. When Wallace was confronted by Kennedy’s federal marshals, and refused the students’ entry, the president nationalized the Alabama Guard. When troops appeared on the scene the governor relented and the Black students entered and registered for classes. That evening from the Oval Office Kennedy appeared on radio and television to deliver what is called the “Report to the American People on Civil Rights” in which he set out the moral and legal issues involved with Civil Rights and proposed legislation that would later become the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the first two years of Kennedy’s term, he had been slow and cautious in his support of civil rights and desegregation in the United States. Ever the politician he was concerned that any bold actions or initiatives on his part in this area would alienate Congressmen he needed to get through his stalled legislative agenda. On June 11, 1963 in a radical departure from his and the nation’s past Kennedy gave his full-throated endorsement to Civil Rights and Civil Rights legislation in this 13-minute speech. Later that night, in the early hours of June 12, 1963, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who had been listening to Kennedy’s remarks on the radio, was killed by a sniper as he returned to his home in Jackson, Mississippi. On June 13, 1963 82 black marchers protesting Evers’ death were arrested by Jackson police. On June 19, 1963 Kennedy asked Congress to introduce his bill to desegregate public facilities, take federal action to end job discrimination, and allow the U.S. Attorney General to start desegregation suits. In the meantime, as Congressional negotiation and debate was beginning on the Civil Rights bill, Kennedy asked civil rights leaders to suspend protests and marches which they refused to do. Instead, in the face of a Congressional filibuster of Kennedy’s civil rights bill, they announced a March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, D.C. to take place in August 1963. Within a week of Evers’s murder, a white suspect was arrested and charged with the slaying. See- Kennedy and the Press, edit. Harold W. Chase and Allen H. Lerman, introduction by Pierre Salinger, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, 1965, p. 452.

Texas motorcade & remarks at the dedication of the Aerospace Medical Health Center, San Antonio – November 21, 1963

White house 1963 – color recording of remarks for “Seas around us”.

Moon speech, Rice University, Houston, Texas – September 12, 1962.

On April 27, 1961, President John F. Kennedy delivered his 2400-word+ major speech known as “President and the Press” before the American Newspaper Publishers Association at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. In the speech delivered just days after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion the new president made a plea for responsible journalism in the face of Cold War threats. The remarks remain relevant today on the topics of press freedom, misinformation, and national security.

This explanatory article is periodically updated.