FEATURE Image: Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi), Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1598, oil on canvas, 56 ¾ x 76 ¾” 145 x 195cm Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome. https://barberinicorsini.org/opera/giuditta-e-oloferne/ – retrieved October 12, 2024.

INTRODUCTION.

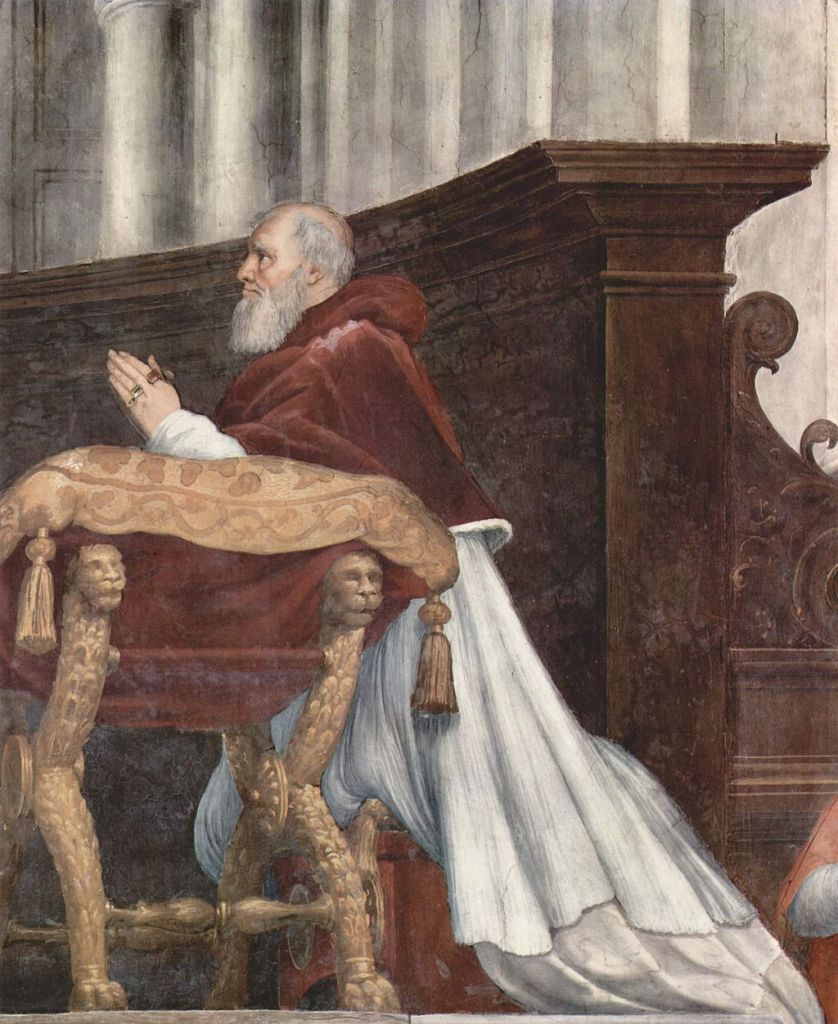

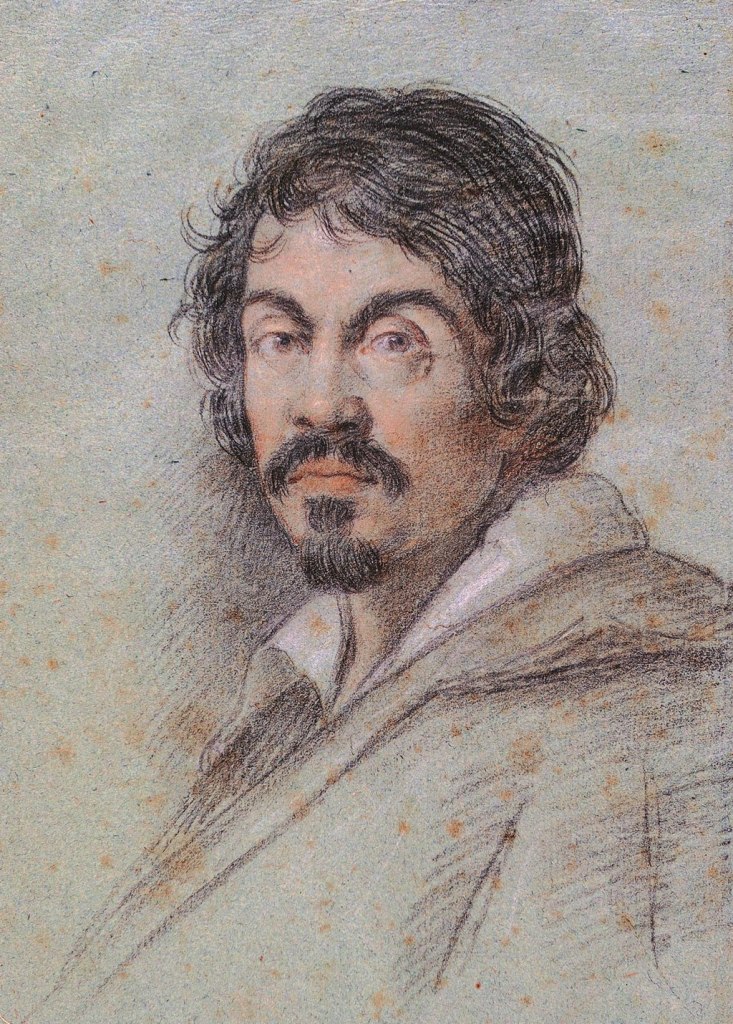

The chalk portrait above is probably the most faithful likeness of Caravaggio. Born Michelangelo Merisi in 1571, Caravaggio became an influential figure in Italian and European art in and well after his lifetime. He revolutionized painting by his theatrical use of light, dramatic narrative, and the naturalistic physical depiction of everyday people. His depiction of figures in historical narrative using dramatic interplay of light and shadow called chiaroscuro along with its naturalistic composition was further modernized in its scenes’ inclusion of the emotional and psychological human state. These artistic qualities were admired and emulated by many young European artists going forward into the balance of the seventeenth century.

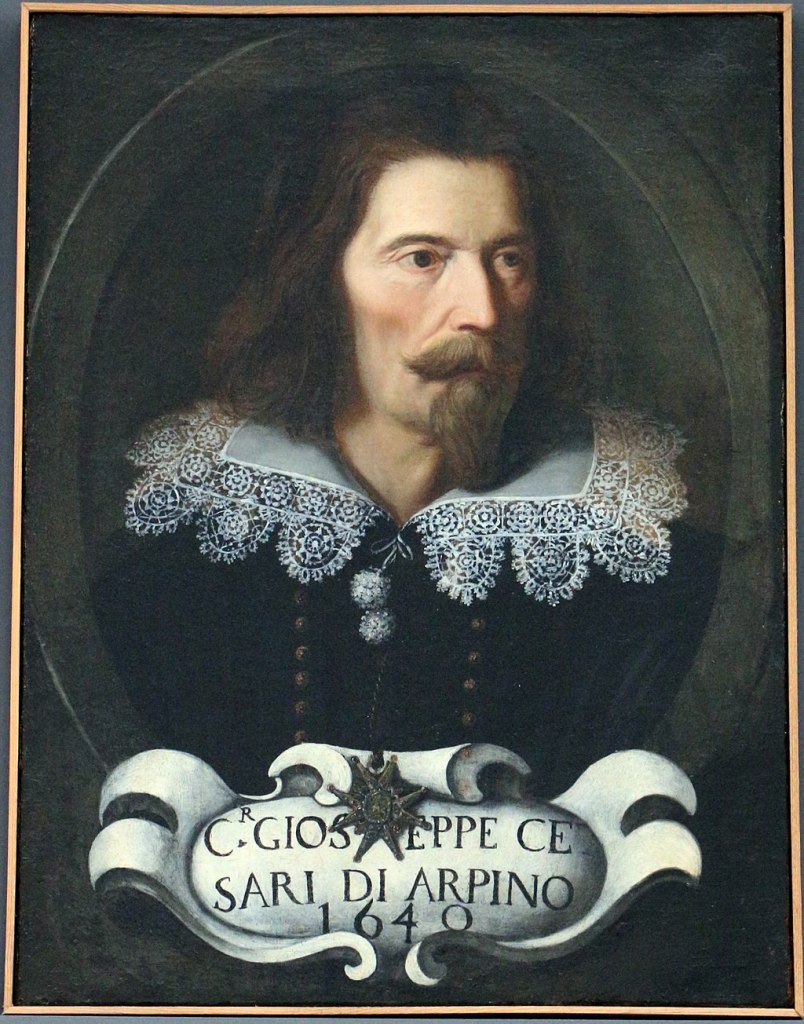

Caravaggio came to Rome around 1592 from Lombardy, where he was influenced by the works of Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo (c.1480-1548), Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480-1557), Romanino (c.1484-1566) and Moretto (c. 1498-1554?). For a while he worked in the workshop of the leading late mannerist Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640), but soon broke away from the established course in Roman-Florentine artistic mannerism. His completely new approach of intense realism and chiaroscuro — that is, dramatic use of light and darkness to situate a scene – made him the “master of darkness” and completely revolutionized art in Rome around 1600. Along with Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610) and Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Michelangelo Merisi, called Caravaggio, was one of the progenitors of 17th century painting.

Artworks.

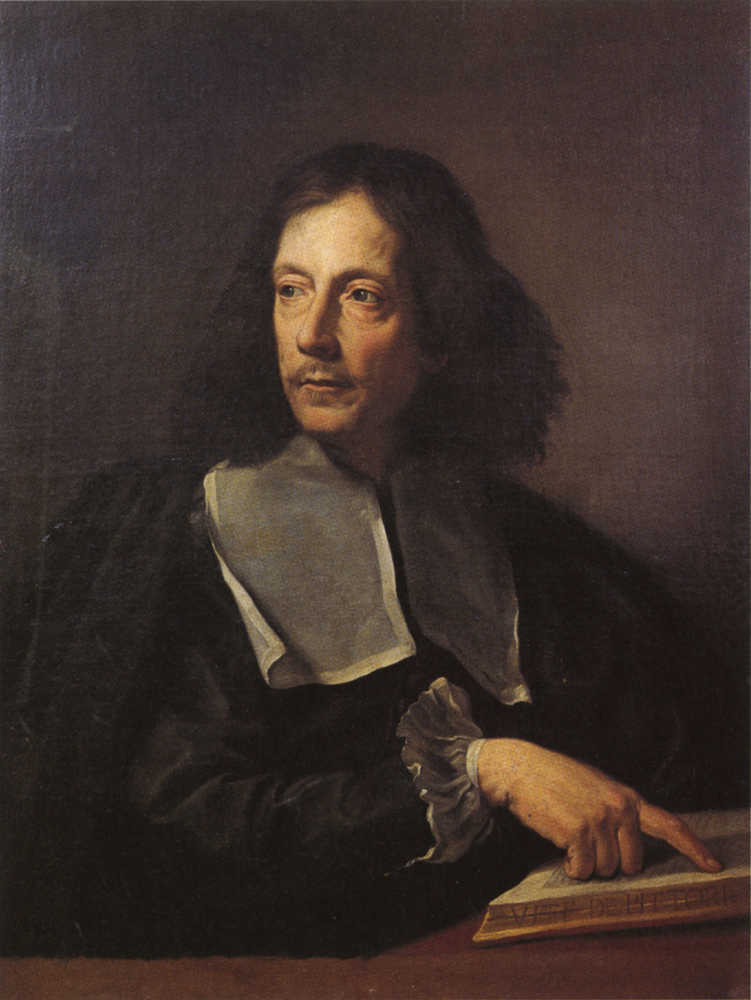

Caravaggio’s Il Fruttaiuolo (“Boy with a Basket of Fruit”) presents a remarkable contrast of the detailed, colorful, and sensuous depiction of fruits of the season and the refined and delicate innocence of an adolescent boy holding its basket. The placid scene of typical everyday life is enhanced by an expressive and careful execution. The model was Caravaggio’s friend, Sicilian painter Mario Minniti, at about 16 years old. According to Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1613-1696) who included Caravaggio in his Lives of the Artists, the artist learned “to paint flowers and fruit so well imitated that everybody came to learn from him how to create the beauty that is so popular today.”

https://www.collezionegalleriaborghese.it/en/opere/self-portrait-as-bacchus-known-as-sick-bacchus – retrieved October 10, 2024.

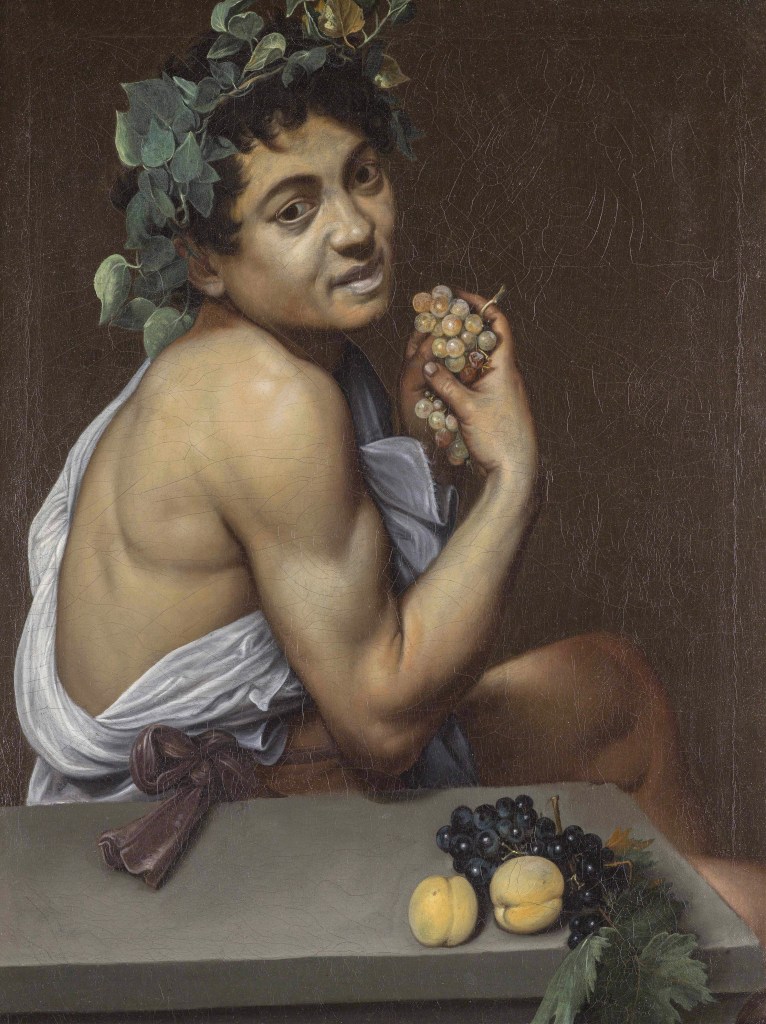

Caravaggio’s Il Bacchino Malato (“The Young Sick Bacchus”), also known as Bacchino malato (“The Sick Bacchus”) or Autoritratto in veste di Bacco (“The Self-Portrait as Bacchus”), is an early self-portrait by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, dated between 1593 and 1594. The artwork dates from Caravaggio’s first years in Rome when he moved to the Eternal City from his native Milan in 1592. The painting was in the collection of Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640), Caravaggio’s early employer. In 1607 it was confiscated from Cesari by the Pope in exchange for the Italian mannerist’s freedom following an illegal firearms charge. The pope gifted it to his nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577-1633), together with the Boy Peeling Fruit and Boy with a Basket of Fruit (“Il Fruttaiuolo“).

The painting is a realist portrait of a young man displaying the typical attributes of Bacchus, the god of drunkenness. The sitter is turned to the viewer in a three-quarter pose, holding in his hands a bunch green grapes held next to his ailing greenish complexion. The sitter has been identified as the artist since it is documented that he was in the Ospedale della Consolazione in Rome around this time for undefined reasons. This interpretation provides the origin for the artwork’s title.

According to Giulio Mancini, Caravaggio painted The Fortune-Teller for a proverbial song while staying with Archbishop Fantino Petrignani (1577-1601). By 1620 when Mancini was writing, the painting was owned by Roman art collector and Catholic prelate Alessandro Vittrici (d. 1650). Later (1657) it was in the collection of Catholic Cardinal Camillo Francesco Maria Pamphili (1622-1666) who sent it with Bernini (1598-1680) to Paris as a gift to Louis XIV.

Playing the game of primero the player at left is oblivious to a bearded cardsharp who uses his gloved fingers to signal to the other player the content of the cards. The other cheater is reaching for a hidden card from his pants behind his back. Caravaggio’s composition is novel with a naturalistic treatment of the figures whose distinct expressions and gestures convey a realistic and hard drama of being cheated and cheating. This painting was owned and stamped by Cardinal del Monte and in his inventory of 1627 following his death. It had been lost for almost a century when it was discovered in a European private collection and purchased by the Kimbell in 1987.

“Caravaggio helped to popularize half-length religious paintings like this, made for private collectors rather than for public church settings. His greatest innovation was in depicting biblical characters as if they belonged to contemporary Roman society, basing them on studio models and dressing them in 17th-century attire, as he does here.” https://www.artic.edu/articles/1071/caravaggio-s-dramatic-life-and-paintings – retrieved October 15, 2024.

The painting was commissioned by Francesco Maria del Monte (1549-1627), a Catholic cardinal and important arts patron in Rome. This is an allegory painting of music manifested by the presence of Cupid in the background, but also a depiction of contemporary performance with individualized sitters, including Caravaggio’s self portrait second from right.

The Lute Player was owned by Cardinal del Monte. It was sold to Vincenzo Giustiniani (1564-1637), an aristocrat Italian banker, art collector and intellectual, and appeared in his inventory in 1638. Caravaggio’s model for the painting is the same as for The Musicians.

Commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, the figure of St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 287-c.305) is Fillide Melandroni, a Roman prostitute (or courtesan) who played a significant role in Caravaggio’s art and fortunes. Young artists turned to prostitutes as their models since other women in respectable society were unavailable to them in that role. Richly dressed in robes, and kneeling on a cushion with a palm frond, Catherine fills the picture as she poses naturally fondling a sword and leaning upon a breaking wheel — signs of the manner of her martyrdom — in a dramatically lit scene of chiaroscuro characteristic of Caravaggio. It is the qualities of a picture such as this one that had immense impact on European art in the 17th century.

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy is Caravaggio’s first known religious composition. Acclaimed for his radical poverty and asceticism, Umbrian saint Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) would fast and pray in solitude for 40 days at a time carrying out literally the Bible’s examples of it. By imitating Jesus Christ in the Gospel simply Saint Francis, too, was ministered by angels. In the painting, shepherds sit in an obscured background as the angel and saint are bathed in light. The scene Caravaggio represents took place in September 1224 on Mount La Verna in central Italy. In that time and place St. Francis received the wounds of the crucified Christ, called the stigmata, one of a handful of saints to have received them. It is partially visible in Caravaggio’s artwork on the side of Francis’ tunic. Caravaggio painted Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy in Rome for the Genoese banker and art collector Ottavio Costa (1554-1639). In 1943, this painting became the first Caravaggio to enter a public collection in the United States.

La fête champêtre is a musical picnic whose tradition originated in Italy. Caravaggio’s composition is lyrical and complicated. As it is in the setting of the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt in Matthew’s Gospel, the characters are dressed humbly accompanied by the presence of an angel.

Mancini relates that Caravaggio painted the subject when staying with an old Catholic prelate named Pandolfo Pucci. By the end of his residence Caravaggio nicknamed his temporary benefactor Monsignor Insalata, or “Mister Salad,” for the pittance of solid food he served his artist boarder. The mock heroic painting may be allegorical with the lizard conveying its traditional meaning of lust or death joined to cherries symbolic of love and roses that of sexually transmitted disease — and warning of all three. see – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Caravaggio/First-apprenticeships-in-Rome-Pucci-Cesari-and-Petrigiani – retrieved October 15, 2024.

The building and grounds of Villa Ludovisi in Rome, and their rich artwork, includes masterpiece frescoes by Guercino (1591-1666) and other leading lights of the 17th century Bolognese school. Caravaggio’s Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto is his only known oil painting on plaster. Cardinal de Monte purchased the villa and took up residence there in 1596. The cardinal sold it to the Ludovisi in 1621. Bellori relates that the subject matter for the fresco of these gods was to express the cardinal’s interest in medicinal chemistry (today’s pharmaceuticals).

The painting was made for Ottavio Costa. It was later owned by a succession of Roman families until it was acquired by the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in 1970. It depicts a famous scene from the book of Judith in the Bible. Judith, a beautiful, highly respected, prayerful and eloquent widow, is able to enter the tent of an Assyrian general whose army had surrounded Judith’s home, the city of Bethulia, certain to destroy it. Because of Holofernes’ desire for her, he allows Judith to move about freely in his camp and has her join him at a banquet in his tent where he gets drunk. “Holofernes, charmed by her, drank a great quantity of wine, more than he had ever drunk on any day since he was born” (Judith 12:20). Overcome with drink, the fearsome general passes out and is decapitated by Judith, her heroic action saving her people. The Bible tells it this way: “When all had departed, and no one, small or great, was left in the bedchamber, Judith stood by Holofernes’ bed and prayed silently, “O Lord, God of all might, in this hour look graciously on the work of my hands for the exaltation of Jerusalem. Now is the time for aiding your heritage and for carrying out my design to shatter the enemies who have risen against us.” She went to the bedpost near the head of Holofernes, and taking his sword from it, she drew close to the bed, grasped the hair of his head, and said, “Strengthen me this day, Lord, God of Israel!” Then with all her might she struck his neck twice and cut off his head. She rolled his body off the bed and took the canopy from its posts. Soon afterward, she came out and handed over the head of Holofernes to her maid, who put it into her food bag” (Judith 13: 4-10). For Caravaggio, this is his first painting depicting violent action in dramatic and realistic detail. The moment is captured as if in an eternal frieze.

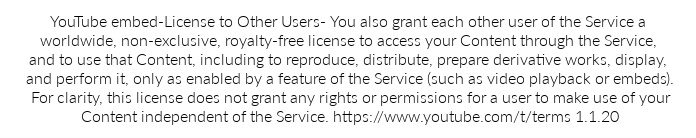

Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini (1568-1644) became the future Pope Urban VIII whose reign began in 1623.

Caravaggio’s Medusa is painted on an actual parade shield.

This is Caravaggio’s only still life painting that has survived. Of course there are still life in his figure paintings as details. His paintings of fruit are completely diverse in terms of varieties and arrangements though sharing overall stylistic similarities. The painting was in the possession of Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564-1631), cousin to Saint Charles Borromeo (d. 1564), and both cardinal archbishops of Milan. Archbishop Federico bequeathed it in his will to the Ambrosiana in Milan, a gallery he co-founded in 1618. The same sort arrangement in the same basket appears in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus in the National Gallery London painted around the same time. Cdl. Borromeo lived in Rome from 1586 to 1601 and grew to become familiar with Caravaggio’s work. It is unclear whether the archbishop commissioned the painting or if it was a gift. Though the Counter-Reformation cardinal was a propagator of the faith using religious art, he also was an avid collector of still life.

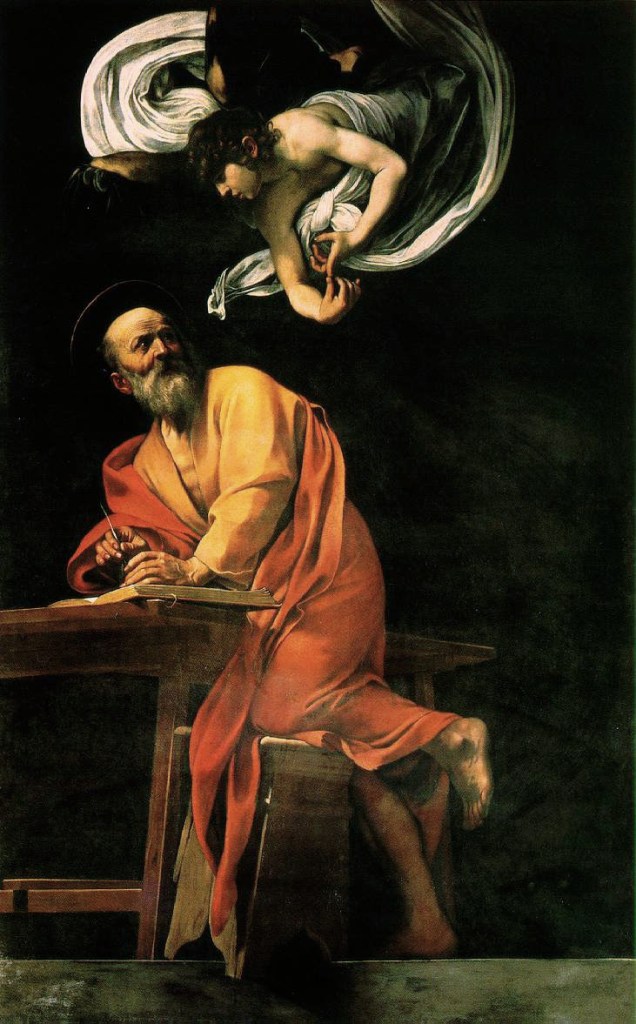

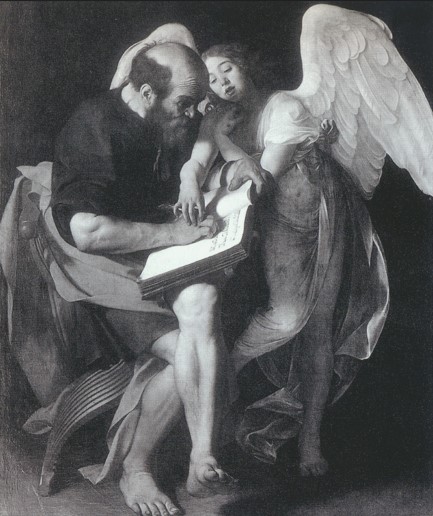

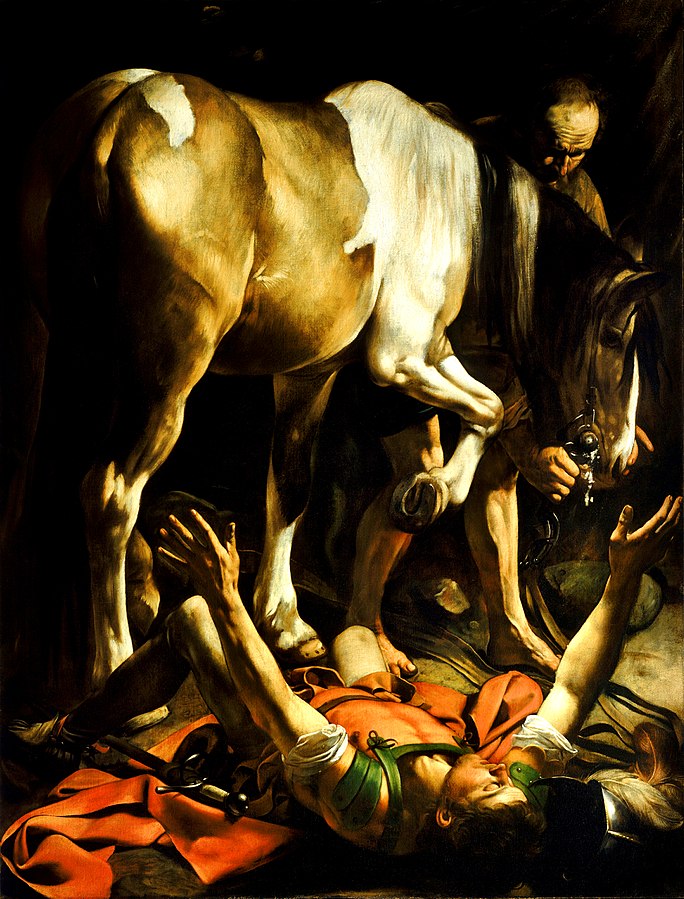

The chapel was purchased by Tiberio Cerasi (1544-1601) in 1600 who worked as Treasurer-General for Pope Clement VIII. Cerasi had the chapel redone by Carlo Maderno (1556-1629). In 1601 Cerasi hired Caravaggio to paint The Conversion of St. Paul and The Crucifixion of St. Paul. Notably, his paintings’ first versions were rejected. The final paintings were installed in 1605 and the chapel consecrated in 1506. The Assumption of Mary over the altar was painted at the same time by Annibale Caracci. See – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerasi_Chapel– retrieved October 14, 2024.

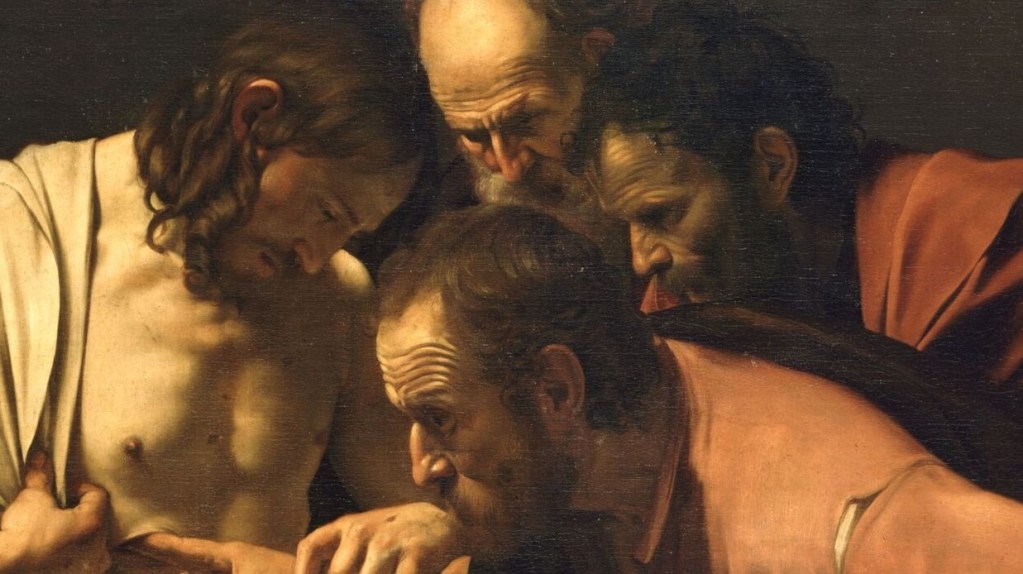

Caravaggio’s depiction of this encounter of a Resurrected Christ with doubting Thomas that is found in the New Testamant (John 20: 27-31) is naturalistic with dramatic chiaroscuro. It was purchased from a Paris art dealer in 1815 after its original owners, the Giustiniani, were forced to sell their collection due to financial distress. Prussian king Frederick William III (1770-1840) bought the collection of paintings with the intention of starting a public art museum in Berlin, though this painting ended up being sorted out as “lower quality” perhaps because it shows no signs of Christ’s divinity. Of the five paintings by Caravaggio the king acquired, three ultimately ended up in the museum, including Cupid as Victorious (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie). The Doubting Thomas was hung in the Berlin Palace and, finally, in 1856 hung in the picture gallery in Sanssouci. https://brandenburg.museum-digital.de/object/11898 – retrieved October 11, 2024.

Caravaggio shows Eros prevailing over other human endeavors: war, music, science, government.

Youth With A Ram was painted for Ciriaco Mattei (d.1614), one of the foremost art collectors of his time, and given to Cardinal del Monte by his son before his death. Mattei also commissioned Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus and The Taking of Christ.

The painting illustrates the Old Testament story in which God subjected Abraham to an extraordinary test of obedience by ordering him to sacrifice his only son Isaac (Genesis 22: 1-19). Caravaggio faithfully depicts the crucial moment of this dramatic story, when old Abraham, at the very moment he is about to immolate a screaming Isaac, is blocked by an angel sent by the Lord.

The Deposition, considered one of Caravaggio’s greatest masterpieces, was commissioned by Girolamo Vittrice for his family chapel in Santa Maria in Vallicella (Chiesa Nuova) in Rome. In 1797 it was included in the group of works transferred to Paris in execution of the Treaty of Tolentino. After its return in 1817 it became part of Pius VII’s Pinacoteca.

The painting has been in the Cavalletti chapel in Rome since it was installed at the end of 1604.

The painting was made for a competition with Domenico Passignano (1559-1638) and Lodovico Cardi (“Il Cigoli”) (1559-1613) soon after Il Cigoli first arrived in Rome. Il Cigoli won the compettion and the whereabouts of Caravaggio’s painting until it arrived to Genoa is uncertain. It may be that Caravaggio himself took it to Genoa when he visited there in 1605.

The painting was made for Ottavio Costa who then had a copy made for his chapel in Liguria while the original was lost. It resurfaced in the mid 19th century in England and was acquired by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in the 1950s. Caravaggio reveals the qualities of the saint by his expression and pose. He is sober and downcast with a tense energy as his pose manifests the monumentality of the prophets on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. With his staff he quietly and contemplatively conveys zeal, passion and vitality. There is a sense of his singleness of purpose, joined even to a little madness, as a man driven by making straight the paths of the Lord.

The painting was bought by King Charles I of England (1600-1649) in 1637. After the monarch’s defeat in the English Civil War (1642-1645), he was imprisoned and executed for high treason in 1649. During the Commonwealth (1649-1660), the painting was sold in 1651 and recovered at the Restoration. Caravaggio’s painting depicts the call of the very first disciples in the very first New Testament Gospel by Mark: “As he passed by the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and his brother Andrew casting their nets into the sea; they were fishermen. Jesus said to them, “Come after me, and I will make you fishers of men.” Then they abandoned their nets and followed him” (Mk 1:16-18). Caravaggio depicts Jesus without a beard as he turns back to invite them to follow him as he moves ahead. Fishermen, Simon Peter holds skewered fish on a stick while Andrew points to himself identifying the object of Jesus’s invitation.

As recently as 1987 this painting came to be attributed to Caravaggio and as the original of this painting’s subject matter. In varying copies of the work the furrow in Christ’s brow is painted faithfully though in this original it is not a painted feature but a canvas fold. There are other design features that, after recent cleaning and conservation, point to a later work of Caravaggio. Many small incisions are present in the artwork’s lower layers of paint that is an uncanny method used by the artist to lay out important points on the canvas for his design. Although the attribution can be argued to the contrary – such as the unusual use of the color blue which Caravaggio saw, according to Bellori, as the “poison of colors” – he did use the color and mostly softened as it is here. Blue, for instance, occurs in the Baptism of Christ (National Gallery of Ireland, c. 1603) and the Annunciation (Nancy, c. 1604). At the Supper at Emmaus (Brera, 1605-6) Christ also wears a robe of softened blue. In its telling broad brushwork, restrained colors, and minimal detail the painting was understood to be a Road to Emmaus painting as discussed by Giulio Mancini and Giovanni Baglione. But these early biographers’ references are likely to the Supper at Emmaus (National Gallery London, 1601). Dated stylistically by its economical, shadowed, and expressive manner, The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew appears to be from the period of 1603-1606. This would be before Caravaggio killed Ranuccio Tomassoni (c. 1580-1606) in a brawl and fled Rome in May 1606. During the first years of the 17th century, the sensuous surface detail of Caravaggio’s art had become spare, dark and expressive. Further, The Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew places half-length figures interacting against a stark background, similar to such paintings as Doubting Thomas (Sanssouci, Potsdam) and the Betrayal of Christ (National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), both of 1603. Before this painting reached England, there was a broadly interpreted copy of it that is today in a private collection by Bernardo Strozzi (1582-1644). Strozzi lived and worked in Rome, Genoa and Venice where he may have seen this painting by Caravaggio. When Charles I’s buying agent was later in Italy, he visited the same places as Strozzi had been, except Genoa.

The painting was commissioned in 1605 by members of the powerful archconfraternity of the Palafrenieri who, following the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica, asked the painter for a new work intended to replace an old painting that decorated the altar of their chapel dedicated to St. Anne. Painted within a few months, in April 1606 the work was exhibited and shortly afterwards moved to the nearby church of Sant’Anna dei Palafrenieri where, seen by Scipione Borghese, it was bought by him. For whatever reason the painting was controversial – perhaps the cleavage of the Madonna or the rendering of the nudity of the child – but Scipione Borghese proudly hung it in his own picture gallery. The painting depicts Mary as she crushes a snake – a symbol of sin – at her feet with the help of Jesus and witnessed by Anna, mother of the Virgin.

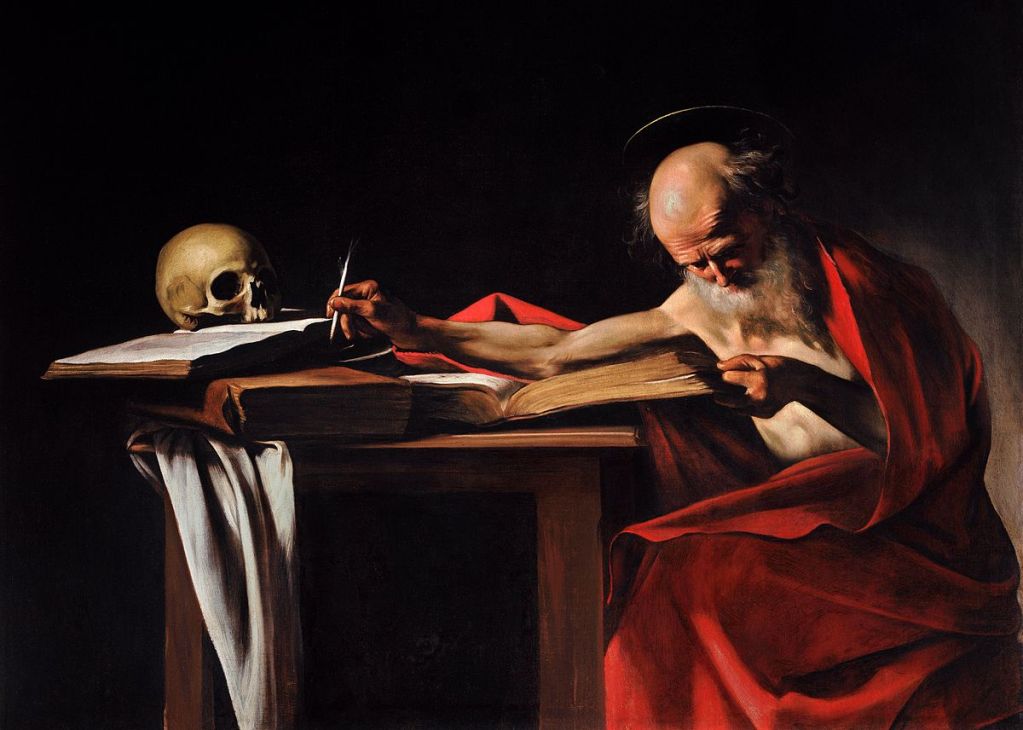

According to Bellori, the painting was made by Caravaggio for Cardinal Scipione Borghese. The cardinal was not only an avid and refined art collector but one of young Caravaggio’s earliest and greatest admirers recognizing the Lombard’s talent despite personality flaws or lack of connections in Rome. The painting depicts Saint Jerome (c. 340s-420), Doctor of the Church, best known for his translation of the Bible from Greek into Latin as well as his commentaries on the Bible. Caravaggio depicts the priest and confessor writing and studying the Holy Scriptures as a scholar, now in old age, who has dedicated his life as a humanist engaged in the complex translation and exegesis of the Church’s sacred text. The composition is divided into large fields of color in warm tones (the saint’s complexion and reddish mantle) and cold tones (the skull and shroud-like white cloth) with Jerome’s arm outstretched with writing instrument in hand across the picture to symbolically portray the unity of the scholar-saint’s dialogue with these opposites of nature including life and death, past and present. As there are many unfinished details in the painting, the artist’s style points to his rapid execution of the work. https://www.collezionegalleriaborghese.it/opere/san-girolamo – retrieved October 13, 2024.

The Seven Acts of Mercy altarpiece was painted between September 23, 1606 and January 9, 1607 for which Caravaggio was paid 400 ducats. The commission required that the artist include the figure of the Madonna of the Misericordia and all the acts of mercy in one vertical canvas and whose overall achievement was a first in Italian art.

The dramatic play of light and shadow throws into relief the melancholic expression on David’s face and the hauntingly lifelike head of Goliath, creating a palpable sense of guilt and redemption that resonates deeply with the viewer.

In addition to developing a considerable name as an artist, Caravaggio was a reputably volatile, bad-tempered and violent man. On May 29, 1606 Caravaggio killed Ranuccio Tomassoni in a fight, the cause of which is disputed, though it may have been over a Roman prostitute, Fillide Melandroni who had posed for Caravaggio several times. The capital crime forced Caravaggio to flee to Naples. A report written by the local coroner declared that the male victim died by Caravaggio’s attempt to castrate him, the code on the Roman street meriting it for a man who insulting another man’s woman. Caravaggio became a fugitive from the law though he continued to paint (Supper at Emmaus) and fled to Naples by the end of 1606. In Naples he painted Flagellation and Seven Works of Mercy, among others. He fled further to Malta and then to Sicily where Caravaggio moved from town to town across the island fearing some unnamed retribution. It was presumed that 38-year-old Caravaggio died from syphilis or perhaps malaria or the Malta Fever though there is current speculation the artist may have been murdered in revenge for his crimes by perhaps members of the Tomassoni family or the Royal Knights. see – https://www.italianartsociety.org/2018/05/on-29-may-1606-the-great-italian-baroque-painter-caravaggio-killed-ranuccio-tommasoni-in-rome/ ; https://thecinemaholic.com/ranuccio-tomassoni-caravaggio/– retrieved October 15, 2024.

The subject was the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta. In exchange for this grand portrait, according to Bellori and Baglione, Caravaggio became a Knight of Malta on an accelerated timetable though soon after the artist fled the island in disgrace.

The famous Caravaggio painting depicting the burial of Santa Lucia once hung in the Church of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro, but today is in Siracusa’s Palazzo Bellomo museum. The original church, built as early as the 6th century, was on the site of Saint Lucy’s martyrdom in the early 4th century. Beneath the sanctuary is a vast labyrinth of dark catacombs dating from the 3rd century which have never been completely explored and are closed to the public. Once containing the tomb of the decapitated saint, her remains were relocated to Venice during the Crusades and where they can be found today. This painting was made by Caravaggio between October 1608 in Malta and early 1609 in Sicily in a commission arranged by his old friend painter Mario Minniti. Caravaggio was on the run in Sicily starting in late 1608 when he arrived into Siracusa, and then onto Messina followed by Palermo. In Sicily, the exile Caravaggio painted Resurrection of Lazarus, The Adoration of the Shepherds (Adorazione dei pastori) and Ecce Homo. In late 1609 he returned to Naples and continued painting, including another St. John the Baptist and, his final artwork, The Martyrdom of St. Ursula. In Naples the artist was attacked in the street by four armed men shortly after his arrival where Caravaggio was seriously injured. see – https://www.frommers.com/destinations/syracuse-and-ortygia-island/attractions/santa-lucia-al-sepolcro; https://www.great-sicily.com/post/the-byzantine-era-in-sicily – retrieved October 15, 2024.

The work was painted for the Church of Santa Maria della Concezione in Messina. Francesco Susinno (1670-1739) states that the commision was a civic not religious one, though apparently the Archbishop of Messina, Franciscan Bonaventura Secusio (d. 1618), supported the project. see – https://federica90.wixsite.com/emozionearte/post/caravaggio-in-sicilia-l-adorazione-dei-pastori-di-messina – retrieved October 15, 2024.

In Malta Caravaggio became a Knight of Malta but got into another violent group brawl where a knight was badly injured. With a warrant put out for his arrest Caravaggio managed to flee to Sicily in October 1608. By December 1608 Caravaggio was found guilty in abstentia and removed from the Maltese order. The commission for this painting came from Giovanni Battista de’ Lazzari, a merchant of Genoese origin who had obtained permission to be buried in the choir chapel of the church of Saints Peter and Paul de’ Pisani (demolished in 1880) in Messina where Camillo de’ Lellis’ religious order, founded in 1591 and dedicated to the care of the sick, had a house. De’Lazzari’s signed contract on December 6, 1608, declared that his new altarpiece would have the Madonna and St. John with saints as its subject. But that was changed to the resurrection of Lazarus (Gospel of John, chapter 11). It is very likely the change was made by De’Lazzari in agreement with the Camillians. According to Susinno, the artwork’s 13 figures were staff members of the hospital where Caravaggio did the painting. see – https://federica90.wixsite.com/emozionearte/post/caravaggio-in-sicilia-la-resurrezione-di-lazzaro – retrieved October 15, 2024.

The Denial of Saint Peter is generally thought to be one of the last pair of artworks by Caravaggio, the other being The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. It was probably finished at Naples in the summer of 1610.

Caravaggio carried this painting and others sailing from Naples to Rome hoping for a pardon from the pope. Instead, when the desperate artist landed he was arrested and the boat was sent back to Naples with the paintings. Caravaggio died on July 18, 1610 in Porto Ercole. The papal nuncio secured this painting for Cardinal Scipione Borghese. see – https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/caravaggios-martyrdom-of-saintt-ursula/ – retrieved October 15, 2024.

LAST PAINTING.

Naples, Galleria di Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano.

Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula was painted in the last month of his life. It contains his characteristic and revolutionary chiaroscuro, naturalism, and depiction of psychological and physical emotion. The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula was commissioned by Genoese art patron Marcantonio Doria. The painting was finished in May and arrived in Genoa in mid-June 1610. Ursula was a venerated but almost completely legendary figure. In typical fashion Caravaggio dispels traditional religious iconography associated with Ursula — a crown, halo, palm branch, the 11,000 virgin martyr companions — for the painful moment in her story when the Barbarian king shoots the arrow into Ursula’s chest that kills her.

Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula marked a watershed in European art. His revolutionary style inspired subsequent generations of painters, such as Artemisia Gentileschi (1593—1651), Giovanni Baglione (1566-1643), and Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639), that became known as the Caravaggisti. He also influenced international Baroque artists including Spaniard Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) and Dutchman Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669). see – https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/the-martyrdom-of-saint-ursula-caravaggio – retrieved October 15, 2024.

SOURCES –

Caravaggio, Gilles Lambert, Taschen, Cologne, 2007.

Caravaggio, Alfred Moir, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1989.

Caravaggio: The Complete Works, Sebastian Schütze, Taschen, Cologne, 2021.

Caravaggio, Timothy Wilson-Smith, Phaidon, London, 1998.

Caravaggio, Howard Hibbard, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1983.

Caravaggio The Artist and His Work, Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Getty, 2012.

This explanatory article may be periodically updated.