FEATURE Image: Paris Bordon/e (1500-1571), Fisherman Presenting a Ring to the Doge Gradenigo, 1534, oil on canvas, 370 x 301 cm (145.7 in × 118.5 in), Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice.

INTRODUCTION TO PART 1.

Venice is one of the great Italian cities for Renaissance art and its wide-ranging influences. Reflecting a city in the sea, its art is characterized by light and color. Its most remarkable artistic production was between 1470 and 1590 – the rise, height, and decline of the Italian Renaissance. Developed into a powerful maritime empire between the 9th and 11th centuries, Venice was an independent city state that rivaled all other Italian maritime empires such as Genoa, Pisa, and Amalfi; and lesser-known Ragusa, Ancona, Gaeta and Noli, and until the fall of the Republic in 1797. From its trade routes Venice inherited and fortified the coloristic tradition of Byzantium and the Eastern Mediterranean, Islamic countries and the Far East, Ravenna along the Italian coast to the south, and Aquileia near Trieste. Trade routes also included to the Free Cities of the North and its medieval Gothic culture. These activities led to a cosmopolitan culture manifested in Venice’s art and architecture. Around 1500 the Republic also had expanded its territorial holdings to a great extent across Italy, Dalmatia, the Alps, and the Aegean Sea.

The Tuscan Renaissance came to Venice starting around 1430 via Padua, a prestigious university town known for its science and philosophy departments, and part of the Venetian state. Artists such as Giotto (c.1267-1337), Filippo Lippi (c. 1406-1469), Donatello (c. 1386– 1466), Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) and Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) brought essential elements of the Early Florentine Renaissance to Venice. Since 1469 Venice was a publishing center and had been a stop since late medieval times for humanist authors such as Petrarch (1304-1374). As the Mediterranean’s dominant naval force, Venice’s cosmopolitan mercantile culture brought financial and human capital to the lagoon city whose concentration spawned technological innovation. Politically, since Venice was a Republic and not a duchy or bishopric, publications and ideas were unencumbered by censorship present elsewhere. For example, Aldine Press established in 1495 began by printing Greek and Roman classics and later worked with leading humanists such as Desiderius Erasmus (1466 – 1536), Pietro Bembo (1470-1547) and Giovanni Pico (1463-1494). The Aldine Press also produced the first proto-type of today’s lightweight and portable paperbacks. By the 16th century over 250 publishing houses operated in Venice making the city a beacon for humanist writers and artists. (see – https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20190708-the-city-that-launched-the-publishing-industry – retrieved December 15, 2024).

These propitious contacts and developments led to the establishment of Venetian Renaissance art by GIOVANNI BELLINI (c. 1430-1516). From an old family of painters, Bellini established a dialogue between Florentine artistic principles of space and form and its philosophy of the natural world with man at the center with Venetian painterly practice. His major discovery was, beginning in his artwork of the 1490s, the situating of naturalistic color to replace the urbane decorative palette used in medieval painting. He also moved past the older mythological subject matter to a naturalistic presentation of religious themes.

Bellini was joined by Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina (1430-1479) who studied with Piero della Francesca (c. 1416-1492) and introduced the influential geometric design to his compositions that influenced CIMA DA CONEGLIANO (c. 1459 – c. 1517). More isolated in his work – and thereby more important for art practice – was the work of VITTORE CARPACCIO (1465-1526) who introduced his synthesis of strict realism, including a sense of space and proportion. Carpaccio captured not only Venice’s contemporary architecture in the work of classicist Mauro Codussi (1440-1504) and sculptor Pietro Lombardo (1435-1515) but its social activity as well. Following Antonello da Messina and Piero della Francesca, Carpaccio used original and expressive colors. Though Carpaccio’s output faded before 1510, Bellini’s work continued until 1516 and through him formed a continuity of style between the late 1400’s and early 1500’s in Venice.

In this first period, GIORGIONE (1478–1510), a student of Bellini, was another important figure in exploring color in Venetian art. Though influenced by Bellini, Giorgione was original in his transformation of his teacher’s stoic elite classicism to a grounding in intimacy and humanity. Many of his religious subjects are based on individualized portraits. In his unidealized landscape painting based on the realism of German Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Giorgione replicates feelings produced in nature rather than rigid archeological reconstructions that Bellini, Mantegna and Donatello produced. Giorgione was also imbued in Flemish painting including Gerard David (c.1460-1523) and Hans Memling (c. 1433-1494). When Giorgione died at 32 years old in a pandemic in 1510, he left to others his melancholic contemplation of the natural world as a direction for Venetian painting, particularly TITIAN (1488-1576) who is to be featured in another post.

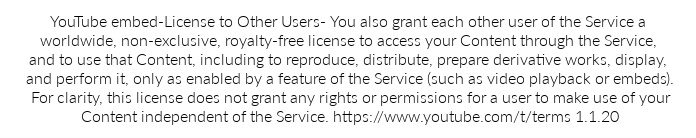

Titian was part of a family of artists who, in 13th-century and 14th century in Italy, had been civic leaders such as mayors, magistrates, and notaries. In Italian his name is Tiziano Vecellio, but in English the artist is famously known as Titian. Titian became the leading painter in Venice and an influential artist throughout sixteenth-century Italy. In the 15th century, two Vecellio brothers had children who became artists. Titian was the grandson of one of those brothers who was ambassador to Venice where the family had a timber trade. A follower of Giorgione, Titian was more intense and dominating in vision and style than the earlier master including his rich dark hues without drawing. Titian also took advantage of Germanic engraving and painting sources for his art, particularly its compositional realism, dynamism and classical references as manifest in Dürer. Though a perfunctory colorist, PARIS BORDON/E (1500-1571) was another artist who came under the influence of Titian’s imperially theatrical style and made a success of it.

There were other artists who followed Giorgione by way of his subject matter rather than, as Titian had, his color. This included artwork of SEBASTIANO DEL PIOMBO (1485-1547), particularly his early Venetian work before he departed for Rome in 1511, and JACOPO NEGRETTI, CALLED PALMA IL VECCHIO (c.1480–1528) who eventually fell into Titian’s orbit but painted arcadian subject matter inspired by Giorgione.

Prolific Venetian artist LORENZO LOTTO (c. 1480 – 1556) retained his independence and highly individual style in a prolific career influenced by Bellini’s composition, Antonello da Messina’s color, and Dürer’s realism. Lotto started in Treviso in 1503 and returned to Venice in 1525 via Recanati, Rome (where he worked with Raphael in the Vatican apartments making his drawing pliant and coloring mellow) and Bergamo. Lotto’s output was primarily deeply spiritual religious paintings and portraits which plumbed psychological depth, and were very popular. In Venice Lotto became one of the leading artists with Titian and Il Pordenone (1484-1539), painting altarpieces, devotional scenes, and portraits for wealthy patrons in the city. Lotto left Venice in 1533 to return to the papal states of the Marches where he intermittently returned to Venice. In 1554 Lotto became a lay brother at the Santa Casa in Loreto and died there in 1556.

ARTWORKS.

Giovanni Bellini came from a family of artists and began work in his father, Jacopo’s workshop. The Bellini brothers Giovanni and Gentile (d. 1507) were greatly influenced by their contemporary Andrea Mantegna who married their sister Nicolosia in 1454. The chronology of Bellini’s paintings is challenging to definitively settle upon since he ran a large workshop of pupils and assistants whose production output was signed with his name. Bellini’s pupils and influences extended to great names of Renaissance Venetian painting: Giorgione, Titian, Palma Vecchio, Sebastiano de Piombo and had influence beyond his direct contacts and into the future. Bellini also studied Donatello so to develop his personal style in the 1450’s and 1460’s. This is manifested in this Madonna and child of which there are several which expresses in light and color harmonious formal three-dimensional beauty and human feeling.

In the mid 1470’s, following a practice popularized by Sicilian Antonello da Messina, Bellini moved from tempura painting to oil. Bellini began to use more rounded figures, also taken from Antonello. He also adapted Piero della Francesca’s perspective system. These artistic elements were evident in Northern European artwork commissioned by Italian families from Rogier Van der Weyden (1399-1464), Hugo Van Der Goes (c.1440-1482), Jan Van Eyck (c. 1385-1441), Petrus Christus (c. 1395-1472), Dieric Bouts (c. 1415-1475) and Hans Memling (c. 1433-1494). Bellini’s oil on panel portrait is the artist’s first. The sitter is of Joerg Fugger, the 21-year-old heir to a wealthy banking family in Germany. Bellini depicts his subject with small blue blossoms in his hair, the sign of a scholar. The portrait is three-quarter length instead of profile and set against a neutral background or, later, with landscape and sky. The portrait informed a coming generation of portraiture and religious images in Italy including Raphael (1483 – 1520), Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), and Fra Bartolomeo (1472-1517).

The 1470’s saw Bellini produce his most glorious landscapes including the warm and glowing St. Francis at the Frick. Specific details about this painting’s provenance are speculative. It is presumed to have been painted in the late 1470’s for Venetian patrician Zuan Michiel, and was destined for the monastery of San Francesco del Deserto on a remote Venetian island. By 1525, the painting hung in the palace of Taddeo Contarini in Venice. (further reading- https://www.frick.org/exhibitions/bellini_giorgione – retrieved December 17, 2024.). Francis is shown receiving the stigmata in a natural mystical light surrounded by a variety of animals. Bellini’s setting for this religious event that took place in September 1224 is a valley in the Venetian countryside (it took place in Umbria), with a small hilltop town in the background and Francis standing outside his hermit’s dwelling. Saint Francis is said to have composed his Canticle of Creatures also in late 1224, considered one of the first masterpieces of Italian verse.

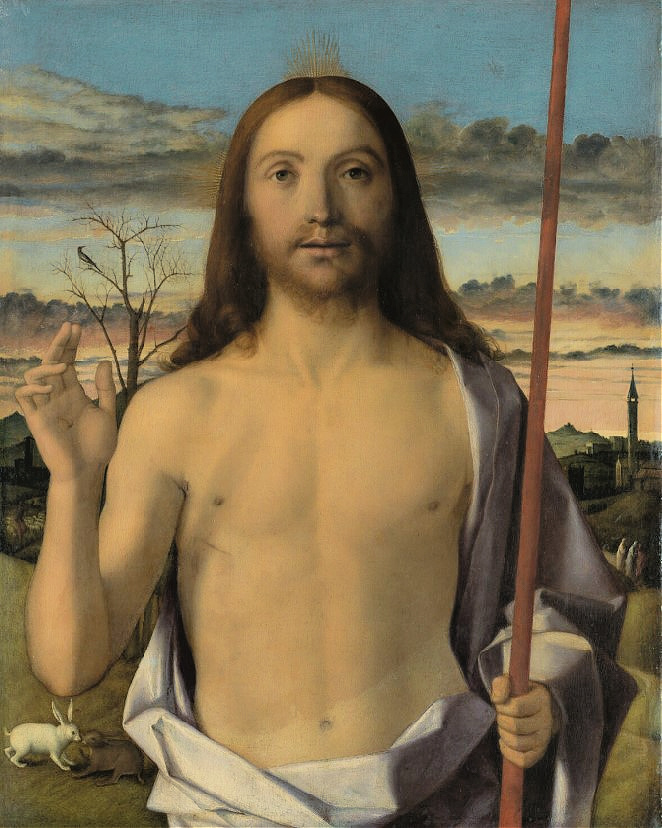

In Bellini’s long career he depicted Jesus Christ differently over time. In his early years he often depicted the dead Christ in a lonely solitude. Later he added angels, and grief-stricken figures of his mother Mary and the apostle John. Bellini developed to depict Christ as triumphant or beatified in his miraculous apparitions of the Transfiguration, Resurrection and Ascension. In Christ Blessing Bellini animatedly portrays the God-Man sent to bless the world on one hand and holding the shepherd’s rod to guide his flock in the other (it may also be logically seen, though not completely in view, as his staff with the traditional red cross on a white flag atop symbolizing his triumph over death). A devotional image presenting the Resurrected Savior, its vibrant figure is brought close to the picture plane where his level gaze and shadowed arm of blessing informs the viewer of the matter-of-fact reality of the scene in quiet harmonious colors. Yet, at the same time, golden rays of light emanate from the top and sides of his head, making thoroughly evident His Divinity. In the background Bellini depicts prolific rabbits, shepherds tending their flock and three shrouded figures who likely are the three Marys at the tomb on Easter morning. There is also a lighted church bell tower to convey the presence of Christ in his Church.

In one of Bellini’s last works the master shows how he adapts his work to the developing artistic style after 1510 led by Giorgione and Titian: the composition is fluid and dynamically conceived, with dramatic realism, aqueous colors and excited brushstrokes. Its attribution to Bellini has been accepted by scholars since 1927 though it remains open to debate.

Cima was a Venetian artist who admired Bellini’s use of color and Antonello’s style of the Netherlandish masters. In contrast to renewed classicism which appeared in Venice in its art and architecture, Cima attempted a sophisticated art reliant on the study of nature that was prevalent in the provinces. Born in Treviso in about 1459, Cima worked in Vicenza in Mantegna’s circle and then moved to Venice in 1492. He was associated with the school of Alvise Vivarini (1442/1453–1503/1505), though Cima remained linked to the gentle and rustic naturalism of the provinces. His models included Madonnas and religious figures in peaceful landscapes such as this painting of a peasant mother and her child in a landscape that includes behind them a monastery and hilltop fortification. The crystalline colors and fluid drawing indicate Antonello’s influence while its overall placidness is characteristic of Cimi’s artwork.

A pupil of Gentile Bellini (Giovanni’s brother), and a follower of Giovanni and Giorgione, his finest work began in 1490. The Legend of Saint Ursula and other pageant-type pictures was early and masterful Italian genre painting. Carpaccio depicted detailed episodes of sacred history and legend using the settings and minutiae of contemporary everyday Venetian society within a formal pictorial schema. This Apparition of the Martyrs of the Mount Ararat in the Church of Sant’ Antonio di Castello is a small canvas that captures the compelling simplicity and authentic emotion of a religious scene that was present in his earlier larger format cycles and series. The painting is of a vision of the prior of St. Anthony monastery kneeling at the altar on the far left. He turns to see the 10,000 martyrs of Mount Ararat he called upon in prayer during a plague that had broken out among the friars. As the martyrs process into the church, they are blessed by St. Peter, the first pope. Carpaccio depicts the interior of a Gothic Church – including an elaborate wooden screen at left and cargo ships suspended from the ceiling – that was demolished in 1807.

Preaching of Saint Stephen by Vittore Carpaccio was done on the first quarter of the 16th century. It depicts the first Christian martyr, St. Stephen, giving a sermon whose actions and words involve its audience as active witnesses. Set within a spacious landscape it reflects an ideal city view, reminiscent to Jerusalem. It is suggested that Carpaccio may have been in Jerusalem as this scene is reminiscent of life in that city and of the Haram-ash-Sharif with the Mosque of Omar.

Carpaccio’s realism in numerous portraits in his ceremonial pictures was influenced by the Flemish masters already popular in Italy in the 1490’s. This bust-length independent portrait of a woman set against a plain dark background is almost an abstract construct of eyes, mouth and hairstyle. Her large head is turned slightly in one direction while her limpid eyes look in the other direction. Her reddish hair is pulled loosely back from her face and, at the crown of her head she wears a yellow net to hold some of it. Her square-neck dress is slate blue edged in black, with a white and gold embroidered front panel. Around her neck she wears a choker of white and black beads.

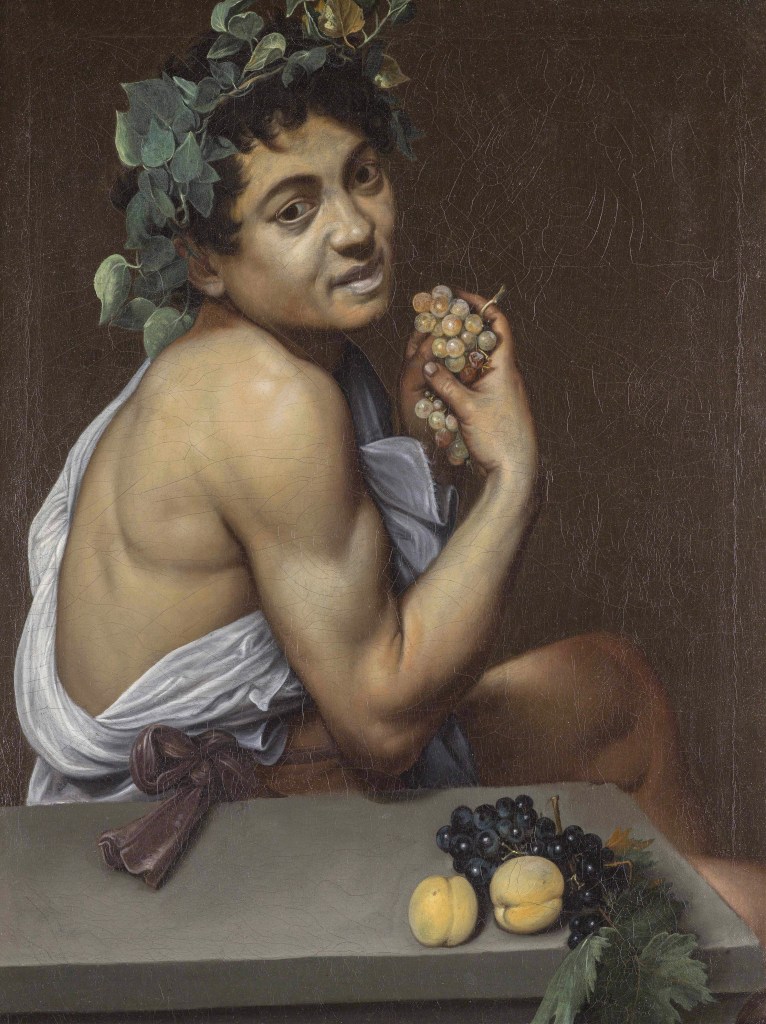

Giorgione who moved to Venice around 1500 is the transitional figure between Bellini and Titian. Instead of a prevailing late 15th century practice of precise brushstrokes and sculptural composition in his art, Giorgio expressed his subject matter in studied tonal gradations of color and precise analysis of human emotional expression described in gentle brushstrokes. Vasari saw Giorgione’s painting as if having no intermediary between art and life. Painted in the same period as Old Woman (Gallerie dell’ Accademia, Venice), this Portrait of a Man epitomizes what Vasari called the “modern manner” where Giorgione sought to paint “living and natural things.” With its plain dark background and close head crop the man’s carefully observed turning gaze and ambiguous expression is wholly engaging and alive.

With Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgione is ranked as one of the founders of modern art. He was the first artist in Venice who often painted small artworks in oil of mysterious and evocative subjects for private commissions instead of public church works. The Tempest, originally commissioned by a Venetian noble of the House of Vendramin, is one of those artworks. Known as “a landscape of mood,” it has no discernable subject matter outside of expressing the tension and heat of an approaching storm. Its meaning remains elusive today. Giorgione’s career and personal life are equally mysterious. The artist is known to have shared a studio with Venetian painter Vincenzo Catena (c. 1480-1531) in Venice, worked on the Doges’ palace (though these works are lost) and on frescoes on the exterior of the German Merchants headquarters in Venice where Titian was working as well in a lesser role. Giorgione was an innovator but his known output is small, questionable, and, dying in the plague in 1510 at 32 years old, sometimes completed by others including his pupils, Titian and Sebastiano del Piombo, who were profoundly influenced by him.

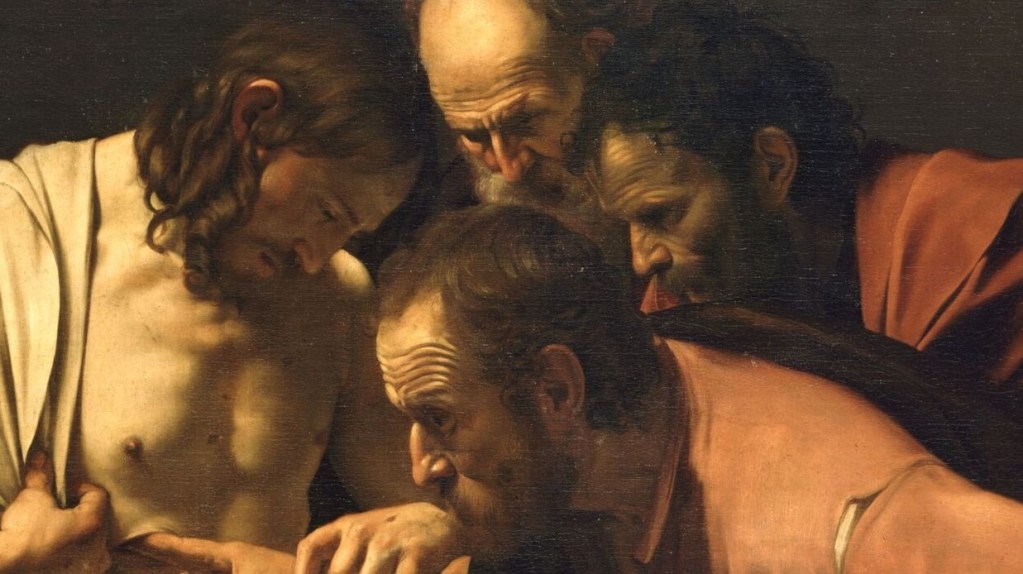

Because of Giorgione’s early death in 1510 and other circumstances he did not complete many of his later paintings, making their ultimate identification difficult. That Titian completed many of these works is documented. Once in the collection of the House of Vendramin, this painting is such of jumble of painterly hands it is today attributed to the Circle of Titian though when earlier it was attributed to Giorgione the hand of Titian was apparent particularly in the figure of Christ. Titian was more aggressive in his use of colors –such as browns and grays- than Giorgione’s refined yellows and blues. X-rays reveal another composition – believed to be Giorgione-like- over the ponderous right hand of the angel painted over it.

When the organ shutter doors closed they formed a single image of two martyrs: Saint Batholomeo and Saint Sebastian. These organ shutters for San Bartolomeo al Rialto are the earliest documented works of Sebastiano. Commissioned by the church’s vicar in late 1507, it was completed in 1509.

St. Louis of Toulouse was a bishop of Toulouse in France consecrated by Boniface VIII in 1297. Because of his princely standing Louis won the episcopal appointment, but as bishop he turned his office and efforts to meeting the material and spiritual needs of the poor in his diocese, feeding the hungry, and ignoring his own material interests. After six months, exhausted by his labors, he abandoned the position of bishop and died at Brignoles of fever, possibly typhoid, at 23 years old. St. Louis of Toulouse is one of the inside panels inside a niche of gray stone and gold mosaic (the other is St. Sebald of Nürnberg) by Sebastiano in his first documented commission.

Sebastiano Luciani, a pupil of Giorgione who deeply influenced him, was born in Venice in 1485. He didn’t become “del Piombo” until after 1531 when he became Keeper of the Papal Seal (“Il Piombo”). After Giorgione’s death in 1510 del Piombo may have completed some of Giorgione’s work and, in 1511, moved to Rome. Working at Villa Farnesina in Raphael’s circle that included Baldassare Peruzzi (1481-1536), del Piombo fell out with Raphael and became a devoted follower of Michaelangelo (1475-1564). Both eagerly worked to outperform Raphael, an artistic rival, and Michelangelo lent del Piombo some of his drawings to work from for some of the main figures in the complex composition of The Raising of Lazarus. The gigantic painting was commissioned for Narbonne Cathedral in southern France by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici (1478-1534), later pope Clement VII, who had also commissioned Raphael’s last painting Transfiguration for the same cathedral.

The pope visited the artist’s studio and was pleased with his original three-quarter length portrait seated in a chair positioned diagonally, and ordered this oil copy on slate. The practice originated in Rome around 1500 in an attempt towards immortality in art. However, the material was heavy and would shatter if not handled with care. After 1531 del Piombo painted rather less and turned to making admirable portraits which combined his Venetian training in color and Roman discipline in form.

Sebastiano made this portrait under the influence of Giorgione in terms of its gentle, engaging expression and subtly dramatic “over the shoulder” pose. Until more recently, this painting was attributed to Giorgione and, as it is Sebastiano, it recalls the deep influence Giorgione had on his pupils who imitated him profoundly. It has been postulated that the sitter is the Florentine general Francesco Ferrucci (1489-1530) who fought in the Italian Wars.

Palma Il Vecchio was a Venetian painter who was a pupil of Bellini and influenced by Titian, Giorgione and Lotto. He is chiefly remembered for his paintings of female figures, particularly a blonde Venetian type of ample charm which extended even to paintings of several female saints. The subject of the naked woman located in a natural setting was pioneered by Giorgione and Titian but Palma Il Vecchio progressed the subject to work out the figure in three-dimensions and reliant on the linear curves in and of a complex assembly and interplay of naked female figures. In this painting, Palma il Vecchio adapted the poses of the sculptors of antiquity and drew on Mannerist contemporaries such as Giulio Romano (1499-1546) and Marc Antonio Raimondi (c. 1470/82–c. 1534). The sensuous surface texture typically found in Venetian art has given way to porcelain-like coolness.

Little is known about Cariani’s biography though it is speculated he was born in Bergamo in or before 1490. In his gentle, soft shaded subjects and arcadian elements Cariani’s early work is Venetian influenced by Giorgione. The artist was also inspired by Bellini and close to Palma Il Vecchio. He moved to Bergamo before 1520 and mastered portraiture under the influence of Lorenzo Lotto which are the highlight of his career. One of Cariani’s masterpieces is this portrait of a man of letters holding a seal that is possibly imperial or papal. The luminous colors are influenced by Palma Il Vecchio while the psychological insight of the sitter is learned from Lorenzo Lotto. The sitter is believed to possibly be Giovanni Benedetto da Caravaggio, a professor and administrator at the University of Padua.

The sitter beats his fist into his chest in penance, lifts an open book of Passion meditations, and is surrounded by a brooding sky and background living scene of Calvary, all of which works for the artist to scrutinize the mental state or inner thoughts of his sitter, here a religious brother in an order of poor hermits. Lotto had studied portraits of Albrecht Dürer, who made two trips to Venice, to learn to convey these deeper psychological states. Lotto’s assertively confessional portraits under his intense handling of light and dourly earthy colors, were astutely new and sometimes rejected by clients.

Lotto, a deeply religious man and one of the most independent of the 16th century Venetian artists, had a highly singular artistic vision with penetrating insight into the human personality. This painting is a mixture of the artist’s realism and idealism. The setting is natural as are the donors who Lotto draws with a Northern European Art sensibility. The Madonna and child are not derived from models, but expressed from an artistic conception of spiritual superiority. Kneeling donors in profile with the Virgin and Child was a motif developed in Venice in the 1490’s by Bellini. From the medieval period forward, donors were frequently portrayed in artworks they commissioned and such was more popular than ever in the early 1500’s.

While strongly influenced by Bellini at the start Lotto developed an independent chameleon-like style influenced by a range of contemporary Renaissance artists such as Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), Fra Bartolomeo, Raphael, Corregio (1489-1534), Giorgione, Titian, as well as Germans, Dürer and Hans Holbein the Elder (1460-1524). But Lotto’s well-known character of independence had as much an historical context as a personal one. About Lotto, Bernard Berenson observed that the Venetian painter was “a psychological painter in an age which ended by esteeming little but force and display, a personal painter at a time when personality was getting to be of less account than conformity, evangelical at heart in a country upon which a rigid and soulless Vaticanism was daily strengthening its hold” (quoted in Pignatti, page 66). This painting from the 1520’s is remarkable for its renewed vision of the picture plane, here with an interlocking group of figures filling a shallow foreground like a frieze and a delimited background.

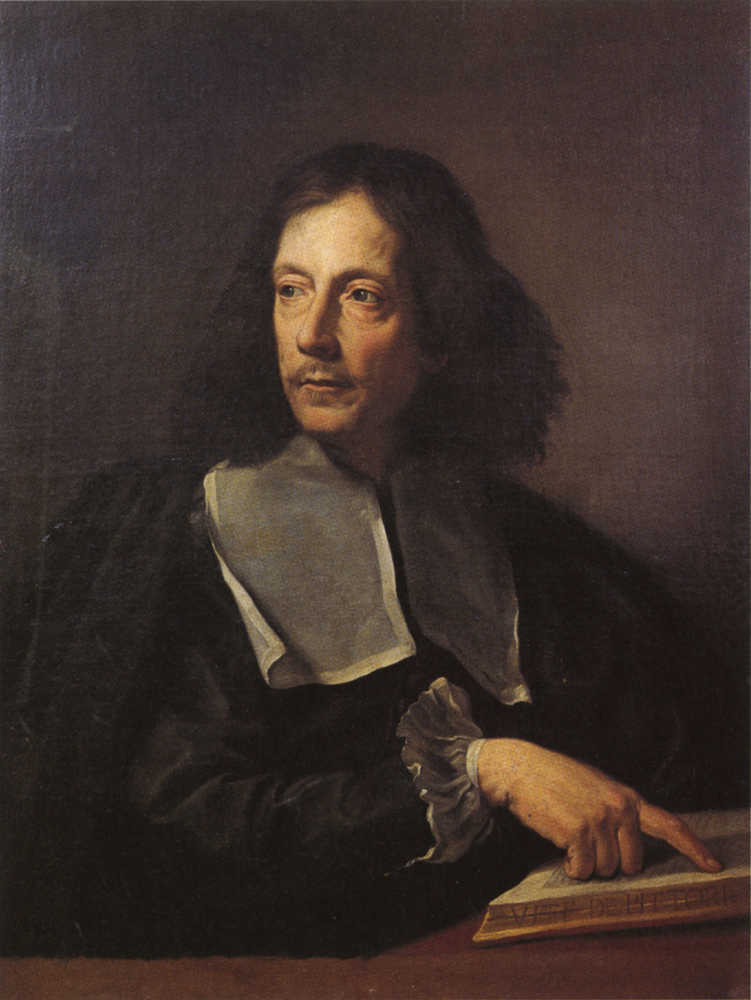

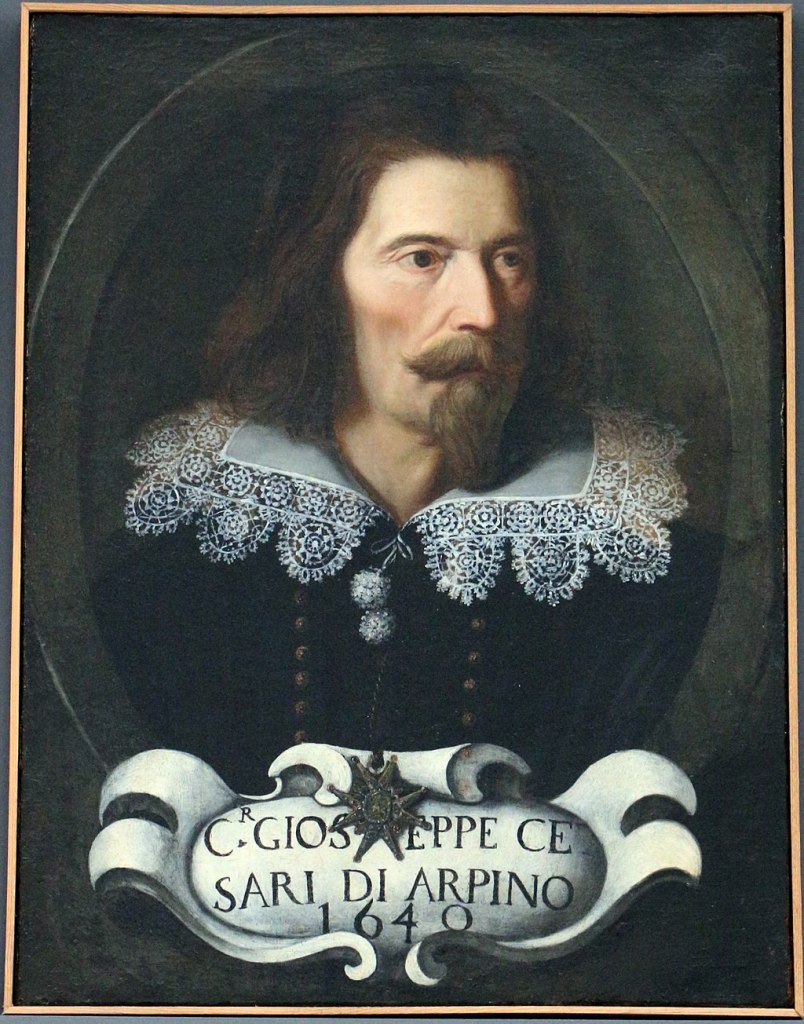

It was painted in Venice for the confraternity of San Marco in 1540. Bartolomeo Gradenigo (1263-1342) was the 53rd Doge of Venice for three years, from 1339 to 1342. He was born in Venice to an ancient noble family and was a rich trader who practiced politics from an early age and lived a life of luxury. The painting depicts a famous legend that occurred in Gradenigo’s reign when a storm was pushed back by the intercession of Venice’s saints. Afterwards the saints gave a humble fisherman the “Ring of the Fisherman” to present to the doge.

Paris Bordon/e was born in Treviso in 1500 and moved to Venice in 1508. where he was based his entire life until his death in 1571. His training is unknown though apparently in Venice where he listed as an independent painter in 1518. As a young professional he reflected the influence of Giorgione in his sentimental portraits and Titian in his use of bold and fluid colors. In the mid 1520s he took on a figural monumentality reminiscent of Pordenone. In the late 1530s Bordon/e was in France at the court of Francis I making realistic portraits and, in 1540, in Augsburg, where he painted for the wealthy Fuggers. Bordon/e was well known for his subjects’ delineated costumes and detailed intellectual landscapes.

Bordon/e’s painting is closely related to Titian’s style yet in this female figure expresses with elegance and refinement Bordon/e’s own sophisticated stylistic vision. This may be a portrait of Veronica Franco, a Venetian courtesan who played an outsized role in the social and cultural life of the city in the mid16th century.

SOURCES: The Golden Century of Venetian Painting, Terisio Pignatti, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1979.

A Dictionary of Art and Artists, Peter and Linda Murray, Penguin Books; Revised,1998.

History of Italian Renaissance Art, 2nd edition, Frederick Hartt, Harry N Abrams. 1987.

Architectural History of Venice, 2nd edition, Deborah Howard, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2004.