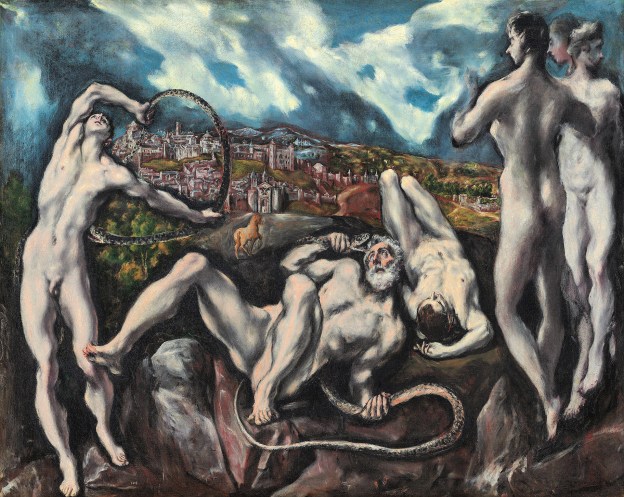

FEATURE Image: El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), Laocoön, oil on canvas, 1604-1614, 55 7/8 x 76″, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. In Greek and Roman mythology, Laocoön is a Trojan priest who warned the Trojans to destroy the Trojan Horse sent by the Athenians and is punished with death by the gods for it. See the artwork again below for details about El Greco’s painting.

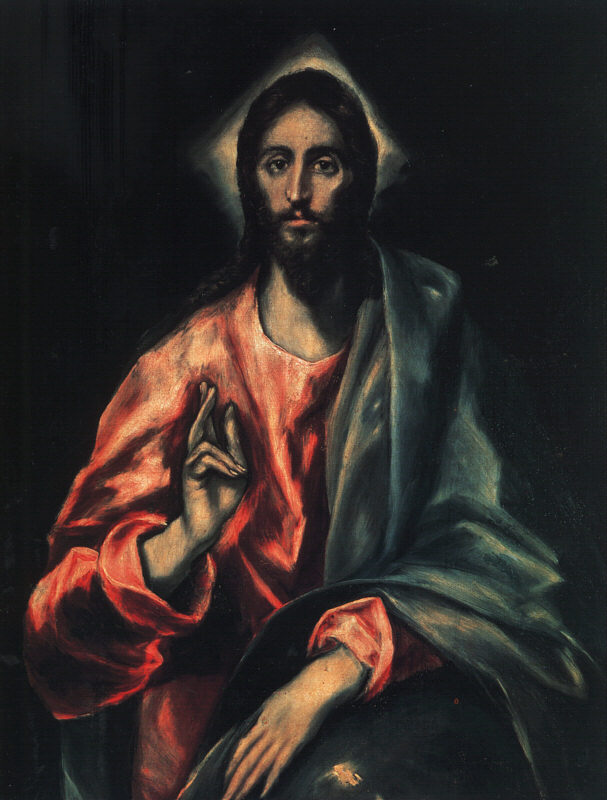

From the museum label: With his intensely personal style, El Greco (“the Greek”) is one of the most original artistic visionaries of any era. Born Doménikos Theotókopoulos on the Greek island of Crete, he trained in Venice and Rome before settling in Toledo, Spain, where he painted this picture. Jesus is shown praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, outside Jerusalem, just before his arrest for his teachings (Judas and the Roman soldiers are approaching at the right). His disciples Peter, James, and John sleep at left. The consciously manipulated scale of the elongated figures, the intentionally jarring colors, and the deliberately confusing space (where exactly is the angel in relationship to the sleeping apostles?) add to the drama and emotion of the scene and capture Christ’s spiritual struggle as he agonizes over his coming crucifixion. Combining aspects from all four biblical accounts of the narrative for his own interpretation of the story, El Greco gives visual form to Christ’s metaphor in Matthew 26:42—”Oh my Father, if this cup may not pass away from me, except I drink it, thy will be done.” see – The Agony in the Garden – Search el greco (Objects) – Search – eMuseum – retrieved December 10, 2025.

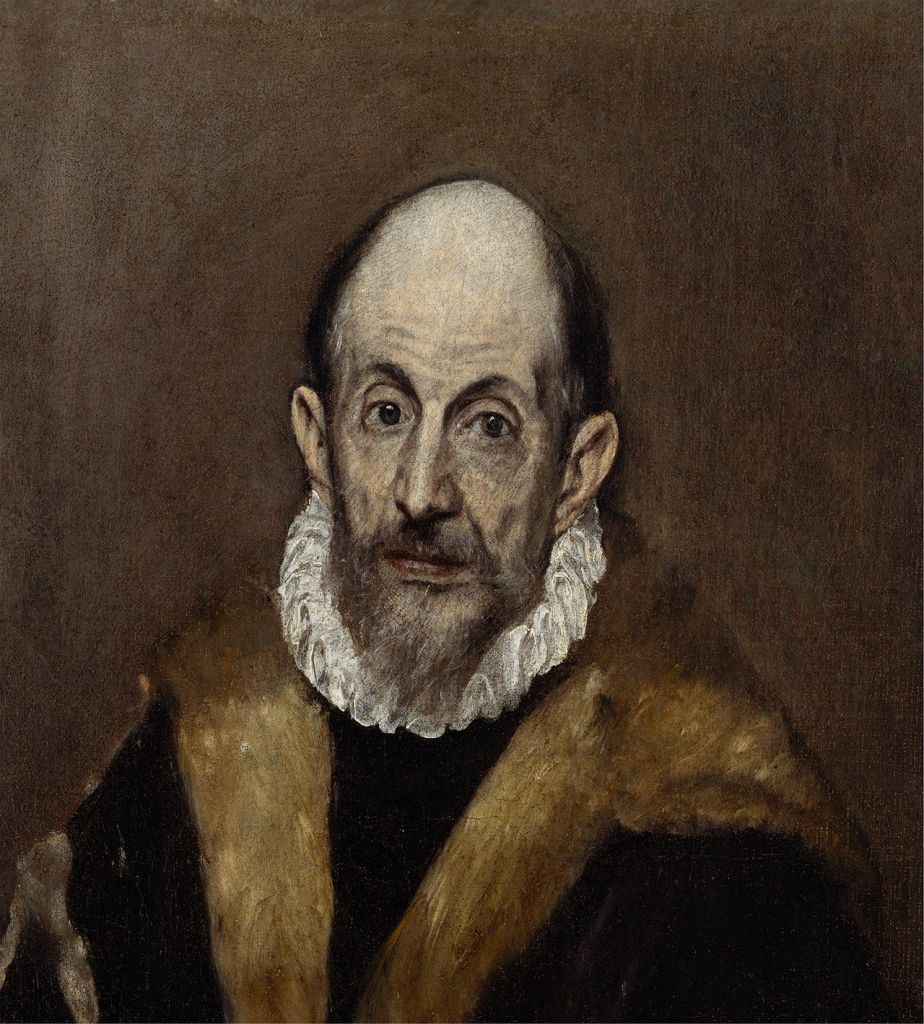

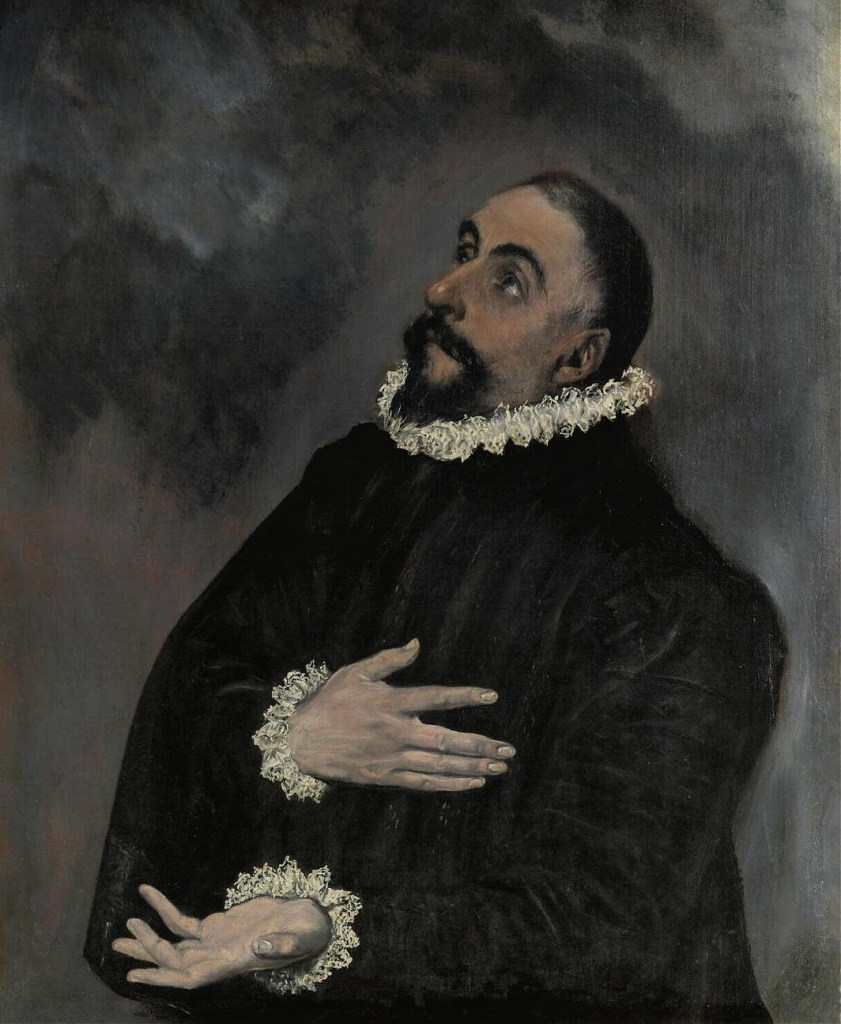

Usually identified as a self-portrait, it is supported by the fact that the same figure appears several times in El Greco’s oeuvre and ages alongside the artist. The portrait shows the influence of Titian (1489-1576) and Tintoretto (c.1518-1594) whose artwork El Greco saw in Venice.

THE ARTWORKS:

Part of an altar ensemble, Assumption of the Virgin is 13 feet high and 7 feet 6 inches wide. In the painting there are two principal groups – the Virgin and angels above and, below, the 12 apostles and an empty sarcophagus. It was the first major commission for El Greco for the Bernadine Convent Santo Domingo el Antiguo in Toledo, Spain. It was in the funerary chapel of Doña María de Silva. El Greco in Spain is first recorded on July 2, 1577 (Toledo Museum of Art, El Greco of Toledo, (exhibition catalog), Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1982, p.16). On August 8, 1577 a contract was made for the main altar series which included The Assumption of the Virgin. El Greco agreed to complete the project in twenty months for a payment of 1500 ducats. The artist signed and dated The Assumption in 1577 and was paid in full in 1578. The painting was installed in September 1579 and remained in the church for the next almost 250 years. (Ibid., p 152; Wood, James, AIC – Essential Guide, Chicago, 2003, p.131). In 1827 The Assumption of the Virgin was purchased by Infante Don Sebastián Gabriel de Borbón (“S.G.”). An inventory of S.G.’s estate lists The Assumption as #26, one of only two sixteenth century Spanish paintings in his collection of more than 200 works. The listing reads: “Otro en id de 14 pies y 5 pulgadas de alto por 8 pies y 3 pulgadas de cnaho. Su asunto, la Ascension de la Virgen, y los Apóstoles, alrededor de Sepulcro. Esta restaurado por Bueno. Tiene marco tallado y dorado…Dominico Greco.” [“Another in dimension (ideación) of 14 feet and 5 inches high by 8 feet and 3 inches wide. Its subject, the Assumption of the Virgin, and the Apostles, around the sepulcher. It was restored on the up and up. It has carved and gilt markings.” – my translation.] (Agueda, Mercedes, “La colección de pinturas del infante Don Sebastián Gabriel,” Boletín del Museo de Prado, iii/8 (1982), pp.103 and 106; 102-17; American Art News, Jan. 7, 1905, Vol. III, p.1.; Toledo Museum of Art, El Greco of Toledo, p.153). In 1837 S.G.’s collection of paintings was confiscated because of his political (pro-Carlist) activities. Along with pictures acquired from the suppression of the religious orders during the Napoleonic occupation (1800-12) his collection of paintings (including presumably #26 in his 1835 inventory) was exhibited at the Museo de la Trinidad. (Boletín, p. 103; Groveart.com, “Borbón y Braganza, Don Infante Sebastián Gabriel.”) S.G.’s property was returned to him shortly before his death in 1875. The Prado describes events until 1902 like this: “La colección…a la muerte del Infante…fue nuevamente exhibida en publico por sus herederos con motivo de una venta realizada en Pau en 1876, añadiéndose al núcleo primitivo de la colección la parte correspondiente llevada al matrimonio por su segunda esposa, Ma Cristina de Borbón. En 1890, su hijo Pedro pone en venta en el Hotel Druot de Paris parte de la colección y unos años más tarde se hace lo mismo en Madrid, bajo el nombre de la Infanta Maria Cristina. De las tres ventas sucesivas 1876, 1890 y 1902 se desprende como los colecciónistas fueron despojando del conjunto todo lo que podriamos llamar grandes piezas…”[… the collection at the death of the Infante was exhibited anew in public in a sale held in Pau in 1876 for the benefit of his heirs. Adding itself to the primitive nucleus of the collection was that respective part brought to the marriage by his second wife, Mrs. Cristina de Borbón. In 1890, her son Pedro put up for sale at the Hotel Druot in Paris another part of the collection and some years later did the same thing in Madrid under the name of the Infanta Maria Cristina. From these three successive sales of 1876, 1890 and 1902 the collectors were divesting themselves of whatever would be called the great pieces…” – my translation]. It is not yet clear at which of these three sales if any The Assumption of the Virgin found itself. What remained after the final sale in 1902 stayed in the possession of Borbón heirs. (Boletín, p. 104). In January 1905 The Assumption of the Virgin was purchased by Durand-Ruel and exhibited in his Paris gallery. (American Art News, Jan. 7, 1905, vol. III, p.1). Durand-Ruel had purchased it from the Spanish Bourbon family into whose possession it came in 1811. The painting was being exhibited at the Prado when Durand-Ruel purchased it in January 1905. Durand-Ruel was dealing in other El Grecos around that time such as acquiring his Laocoön in 1910 and selling it to Paul Cassirer in Berlin by October 1915 (today it is in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.). On July 17, 1906, The Assumption of the Virgin was purchased by The Art Institute of Chicago for 200,000ff from Durand-Ruel in Paris. This purchase for an American museum reflected the daring and independent judgment of its purchasers. The painting had always been praised as the artist’s most beautiful and was considered a homage to Titian’s composition in the Church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice while also expressing Roman monumentality. (Horowitz, Helen L., Culture and the City: Cultural Philanthropy in Chicago from the 1880s to 1917, Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1976, p. 101; The Art Institute Chicago 28th Annual Report, June 1, 1906-June 1, 1907, pp.20 and 59; Toledo Museum of Art, El Greco of Toledo, p.153). In February 1915 Mrs. Nancy Atwood Sprague, widow of Art Institute of Chicago Trustee Arnold Sprague, gave $50,000 to defray the artwork’s purchase expenses. From the very beginning this El Greco painting was considered the Museum’s most important acquisition of the year and called the greatest work of El Greco outside Spain. (Chicago Art Institute Bulletin, Mar. 1, 1915, p. 34).

The painting of the Holy Trinity was part of the altar ensemble for El Greco’s first major commission. It was above The Assumption of the Virgin with God the Father holding the dead Christ surrounded by angels and a white dove hovering above signifying the Holy Spirit.

El Greco painted this episode of the Purification of the Temple many times, a story that appears in all four Gospels. The artist used intense colors and exaggerated gestures to express the chaos and disruption of the moment when Jesus Christ, angry that the temple was being used for sinful commerce and not prayer, makes a whip and uses it to drive out the traders selling animals for sacrifice. In the upper left corner is a painted sculpture of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden by the Angel of God reinforcing the message of sinfulness in the trader’s actions in the scene. At right in contrast, Christ’s apostles stand beneath a painted relief sculpture of faithful Abraham. The story of the Purification of the Temple told in Chapter 2 of John’s Gospel relates: “…Jesus went up to Jerusalem. He found in the temple area those who sold oxen, sheep, and doves, as well as the money-changers seated there. He made a whip out of cords and drove them all out of the temple area, with the sheep and oxen, and spilled the coins of the money-changers and overturned their tables, and to those who sold doves he said, ‘Take these out of here, and stop making my Father’s house a marketplace.'” El Greco painted Christ’s body energetically twisted with his right arm raised and ready to strike the man draped in yellow cloth he is gazing at. The man in yellow mirrors Christ’s pose as he recoils, arching his back and raising his hand to protect himself. The figures behind him lean in the same direction backwards to avoid being struck in the melée. The painting shows El Greco’s debt to Renaissance art such as Titian and Michelangelo (1475-1564) whose artwork El Greco studied during his travels to Venice and Rome. The figures behind Christ are much calmer. The gray-bearded man with his hand on his knee looking up in a yellow and blue costume is identified as Simon Peter. While the foreground setting suggests a grand columned one that is only partially seen, the buildings in the background with their arched arcades were likely inspired by architecture El Greco saw in Venice in 1568.

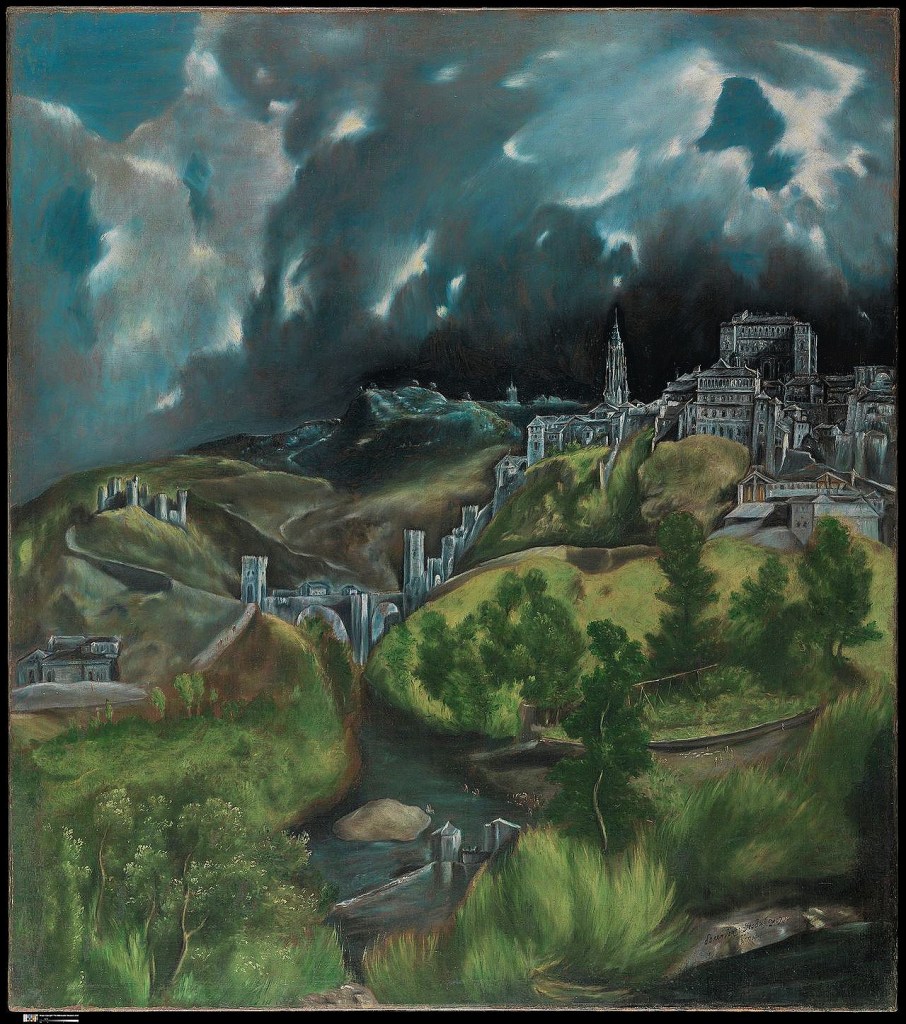

The painting was commissioned by Martín Ramírez for the Chapel of San José in Toledo, Spain. El Greco painted miracles as matter of fact. St. Martin and The Beggar depicts a scene from a low vantage point looking up to a monumental knight sharing his cloak with an attenuated, nearly otherworldly figure of a naked beggar. St. Martin of Tours (d.397), part of the Imperial Calvary stationed near Amiens during the times of Roman Emperor Constantine, sits mounted on a magnificent white Arabian steed and is dressed in stylishly practical soldier regalia from head to foot signifying his noble role and power to survey this emerald green landscape that is Toledo and the Tagus river. Martin’s green cloak is one part of his regalia but, on a cold autumn or winter day, his heart burns to divide it with his sword so to share it with this naked bandaged stranger he meets on the road. The encounter and action are modest and profound simultaneously– a typical social setting yet not merely transactional within a rigidly conceived social order but a tender act of charity. Martin rode off with his half cloak and thought of his soldierly duties. Yet it afforded a miracle. That night, tradition relates, Christ appeared to Martin in a dream revealing that the beggar the knoght shared his cloak with was Him.

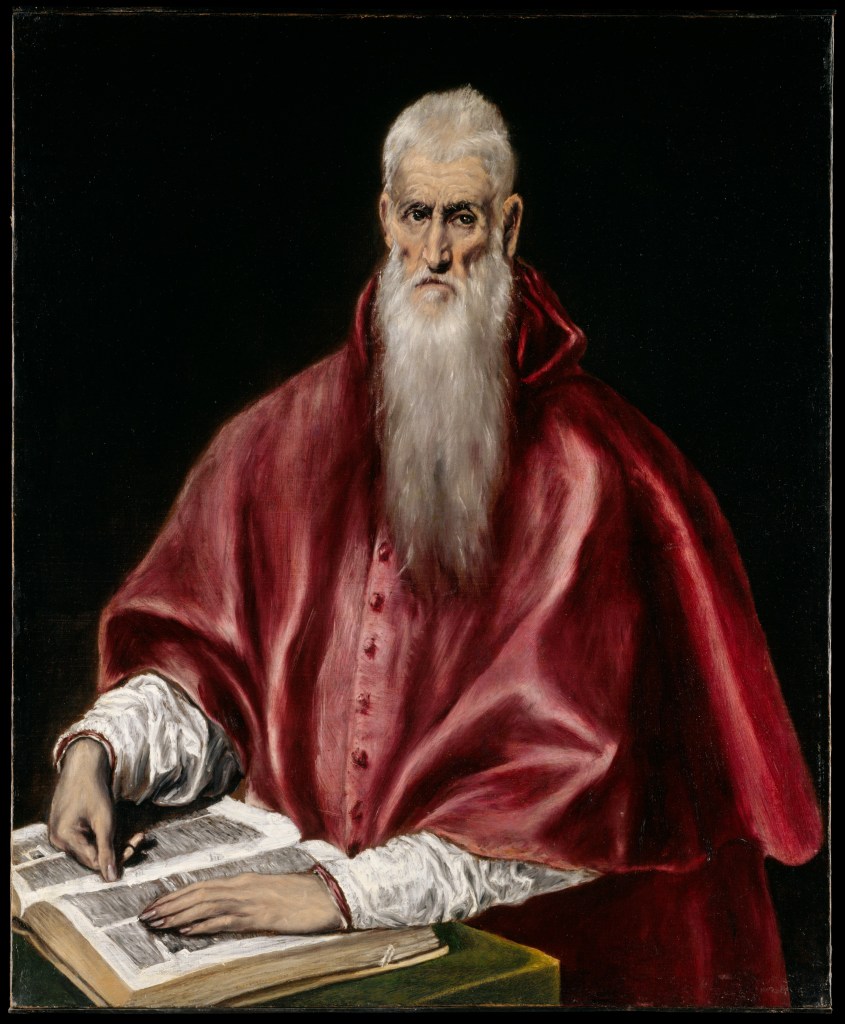

This painting shows St. John the Evangelist in a half-figure which has a clear precedent in the Venetian school where El Greco completed his training. Crete, where El Greco was born, was a Venetian possession. El Greco arrived to Venice as a teenager in the late 1550s or early 1560s where he worked with Titian (c. 1490-1576) but became the admirer and heir of Tintoretto (c. 1518-1594). El Greco, who studied icon painting in Crete, learned the medium of oil from its virtuoso Titian, but once in Venice, El Greco quite normally was attracted to Tintoretto, the city’s then-modern master. “The Greek” did not simply imitate Tintoretto’s exterior forms but very personally emulated his deeply spiritual and expressive Mannerism. In this later painting, El Greco depicts the tradition that John the Evangelist was in Rome when the Emperor Domitian (51-96) tried to assassinate Jesus of Nazareth’s young apostle by poisoning the wine in his Mass chalice. But the legend relates that the poison turned into a fabulous serpent tipping off John and his holy companions and doing them no harm. Like Lorenzo Lotto (c. 1480-1556), El Greco depicts this story’s externals surrounding John – be it the heavy chalice, poisonous serpent exorcised from it, or the expressive hands of the apostle holding the cup of sacrifice and motioning towards it – to scrutinize the inner conviction or character of the sitter, the young author of the Johannine corpus of a gospel, three letters, and the book of Revelation. On John’s Gospel Cornelius à Lapide (1567-1637) wrote that the Evangelist was indeed the eagle (inspired by a description in Ezekiel) who soars skyward and swoops down to earth for his prey. John wrote the last canonical gospel in 99 with combatting that day’s Christian heresies in mind, specifically those that denied Christ’s divinity – whom in his epistles he called “anti-Christs.” John conveys sacred ideas with a rusticity of style. The 17th century theologian and biblical scholar Cornelius à Lapide affirmed that “John was most like Christ” and that the disciple loved the master supremely and the master held the disciple most dear. Because of the relationship of Jesus and John, the biblical scholar claimed, “when you read and hear John [in his gospel, letters, and book of Revelation] think that you read and hear Christ.” He quotes St. Jerome who claimed that Christ transfused his own spirit and his own love including “the purest streams of Jesus Christ’s Doctrines” into Saint John. This relationship is signaled by John’s reclining on the breast of Christ at the Last Supper. John, now in old age, was pressed by all the bishops in Asia and many others to write a “breakthrough” account claiming of the deepest things of the Divinity of the savior. John agreed with the condition that the whole church fast before he embarked on the project and when the fast ended John began: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2He was in the beginning with God. 3All things came to be through him, and without him nothing came to be.” Nothing is stronger to attest to the origin, eternity, and generation of the divinity of the Christ. John wrote in the Greek language because he was addressing Greeks but, again according to Cornelius à Lapide, the gospel is filled with Hebrew phrases and idioms because St. John was a Hebrew who loved his native language. Though John relates Jesus’s miracles as proof that Christ was the Messiah, God as well as man – including the singular accounts of the changing water to wine at the wedding feast of Cana (chapter 2) and the raising of Lazarus from the dead (chapter 11) – John less relates actions of Christ as found in the synoptics Matthew, Mark, and L uke who focused on his humanity and much more of the discourses and disputations that Christ had with the Jews (mostly its rulers), again with none other than the same purpose to prove his theology meant for the whole world that Christ was “God as well as man.” In John’s gospel a careful examination of contexts needs to occur because Christ speaks sometimes as man and sometimes as God. Its high theology which dealt with the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, unity of the Godhead, and divine relations and attributes became that gospel in the next centuries that the bishops referenced to combat their day’s heresies such as Arianism (which denied Christ’s Divinity), the Docetists (who denied Christ’s humanity), and Nestorians (who denied Christ’s dual natures). John had favorite terms and ideas he repeated in his gospel – calling Christ “the Life” and “the Light.” Calling saints “the children of light.” Calling sin “darkness.”

As mentioned in the feature image caption, Laocoön is a Trojan priest in Greek and Roman mythology who warned the Trojans to destroy the Trojan Horse sent by the Athenians by which they won the war. “I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts,” he told them (see Edith Hamilton, Mythology, p. 285). Laocoön and his two sons are punished for revealing this truth by the gods. They are attacked by giant serpents sent out of the sea by Apollo and Artemis that bit and crushed them to death and then slithered away into Athena’s Temple in the city. The Trojans, instead of heeding their priest’s warning and seeing his death for what it was — the punishment for telling them the truth of the danger of the Trojan Horse — viewed it as warning not to question the entry of the monumental wooden horse into the city. They pulled it in, set it in front of Athena’s Temple, and went to their homes believing they had won a peace that had not happened in ten years. El Greco set the artwork outside Toledo giving the ancient tale a contemporary context and unique interpretation. Though Laocoön and his two sons’ fates are sealed, the artist captures a unified centrifugal movement with individualized figures in bare-faced struggle after exercising their prudential judgment that is witnessed by dispassionate onlookers as if in a dream.

SOURCES:

El Greco, Leo Bronstein, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 1990.

El Greco of Toledo, Jonathan Brown, William B. Jordan, Richard L. Kagan, Alfonso E. Perez Sanchez, Little, Brown, Boston. 1982.

El Greco, David Davies, National Gallery Company, London, 2003.

Mythology Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, Edith Hamilton, Grand Central Publishing, New York and Boston (originally published in 1942).