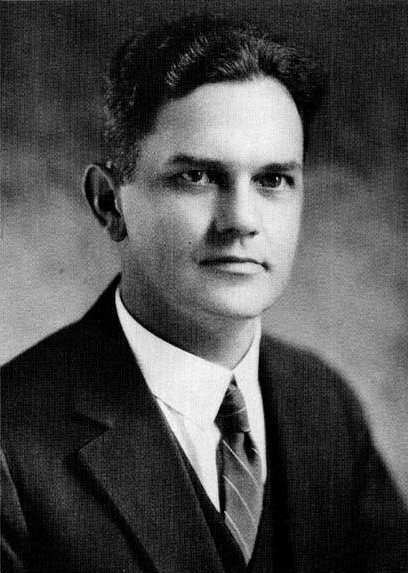

FEATURE Image: February 2018. Village “Art” Theatre, 1548-50 N. Clark Street, Chicago, Illinois 60610. The use of masks had been used in theatre since ancient times. They were usually tied to their dramatic source material and the inherent psychology of the characters. The Landmark Designation Report for the Village Theatre described this polychrome character head with musical instruments as “singing” in honor of the neighboring Germania Club, a German social club with its origins in men’s choral music. The head also wears a Baroque-style “wig” of oak leaves and acorns. In Germany, oak trees are revered, and acorns are a symbol of good luck. A decorative keystone on the theater’s round-arched window also has an acorn ornament. 88% 7.94mb DSC_4799 Author’s photograph.

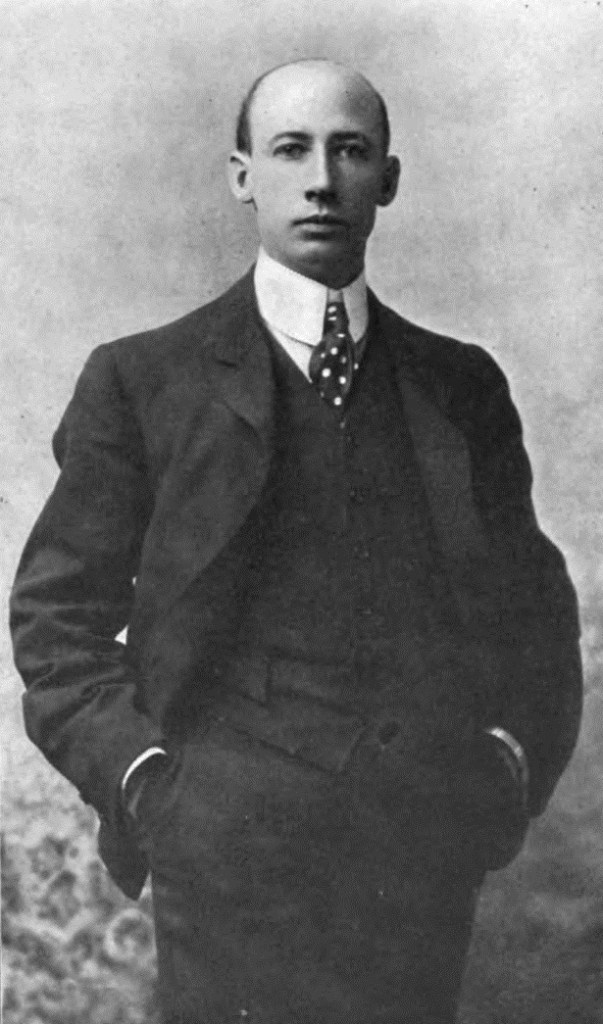

Designed by architect Adolphe Woerner (born Stuttgart, Germany 1851- 1926), the Village (Art) Theatre opened as the Germania Theatre on July 29, 1916 and closed in its 91st year in March 2007. The building was erected by German-born Frank Schoeninger exclusively as a movie theater for $75,000 (about $2.2 million in 2025) and leased for an annual $7,000 rent (about $205,000 today) to Herman L. Gumbiner (Germany, 1879- 1952, Santa Monica, Calif.) in a 10-year contract with his company, The Villas Amusement Company (later Gumbiner Theatrical Enterprises). By 1910, buildings erected solely for the purpose to showcase motion pictures were becoming increasingly popular as the appetite to consume the latest silent motion pictures out of Hollywood was booming everywhere. These neighborhood movie houses, larger than dingy storefront nickelodeons and yet smaller than flamboyantly ornate vaudeville theatres, had movie “palace” touches while fitted conveniently into Chicago’s many local commercial strips. Nearly all of these first-generation movie theaters in Chicago have been demolished or remodeled for other purposes including those larger-scale theaters developed by major theater operators such as Balaban and Katz, Lubliner and Trinz, and the Marks Brothers. While those palatial theatres could hold between 2,000 and 4,000 movie-goers the Village Theatre, one of the last and best first generation movie houses to survive for so long, originally held 1,000 spectators. Originally named the Germania Theater because it was next door to the Germania Club, it looked to attract affluent club members to its flicks.

Herman Gumbinger was a major film exhibitor who was busy in Chicago building his independent theatre chain in the 1910’s, with several new movie house projects and acquisitions throughout the city’s northside primarily. After building Chicago’s first independent movie house chain in the teens, Gumbinger relocated to Los Angeles, California, in 1921 where he built the famous Los Angeles Theatre in the Broadway Historic Theatre District of Downtown L.A. Erected at a cost of over $1.5 million ($31 million today) and designed by renowned movie theatre architect S. Charles Lee (1899-1990) Gumbinger’s theatre premiered Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. Gumbinger Theatrical Enterprises finally dissolved in 1943.

The Germania was one of the first-generation movie theatres built at the intersection of three Chicago neighborhoods – Gold Coast to the south and east, Old Town to the north and west and Lincoln Park to the north. An architectural mix of styles including Classical Revival (triangle pediments, pilasters and cornice with dentils fashioned in terra cotta) and Renaissance Revival (rusticated exterior and round-arched windows with keystones), the movie house also incorporated Germanic symbolism in its details reflecting the area’s then prominent ethnic group. During World War One, in a wave of anti-German sentiment, The Germania Club renamed itself the Lincoln Club. It changed its name back in 1921. The Germania Theatre changed its name to the Parkside and never looked back. In 1931 until 1962 it was known as the Gold Coast theatre. Meanwhile, prohibition closed down Frank Schoeninger’s tavern and he left for Wisconsin. In the 1960’s the theatre was updated and renamed the Globe Theatre. In 1967 the building was renamed the Village Theatre after it survived being demolished by the nearby Sandburg Village development.

The original two-story façade of red pressed brick and white beige glazed terra cotta decoration competed with a sizeable modern marquee that was removed before its demolition in 2018. Since after college I lived in Chicago for about 15 years, I recall seeing several films here. The ones I can remember seeing at the Village Theatre were Wall Street, House of Games, Fatal Attraction, Russia House, Michael Collins, and The Red Violin, among others of that period. In early 1991 the interior of the theater was divided into four screens and I didn’t stop going to movies there but just not as frequently as I did before. In April 2018, the Village Theatre and neighboring buildings along North Avenue were completely demolished to make way for construction of a condominium building. The ornate Clark Street frontage was stabilized as everything else crumbled to dust around it. The façade was repurposed to serve as the entrance for the new condo development known as Fifteen Fifty on the Park with units priced at opening at $1.625 to $5.85 million.

This explanatory article may be periodically updated.

SOURCES:

https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/zlup/Historic_Preservation/Publications/Village_Theatre.pdf – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://chicago.curbed.com/2019/2/28/18233421/condo-construction-village-theater-fifteen-fifty-park – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://www.urbanremainschicago.com/news-and-events/2018/06/03/chicagos-historic-village-theater-reduced-to-facedectomy-after-auditorium-demolished?fbclid=IwAR1IIsjQszVYuZ2mMhNy5QD1LHLP4UcAW-SmxegKhc2xZ2BeTLJUAng4YmY – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/409 – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107764067/adolf-woerner – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://buildingupchicago.com/tag/avoda-group/ – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://www.friedrich-verlag.de/friedrich-plus/sekundarstufe/schultheater/theatertheorie/maskerade-im-theater-und-im-alltag-3524 – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23567141/herman_louis-gumbiner# – retrieved May 3, 2025.

https://www.chicagohistory.org/germania-club/ – retrieved May 5, 2025.